Chapter 8 Open Component Separation ![]()

1 Surgical Anatomy

A clear understanding of the anatomy of the abdominal wall is critical when performing a component separation operation. The two vertically oriented rectus abdominis muscles, with their overlying anterior rectus sheaths should normally lie side by side in the midline. In between the rectus muscles is the tendinous linea alba, which functionally is actually the tendinous insertion of the fascial extensions of the six lateral abdominal wall muscles (bilateral external oblique, internal oblique, and transverses abdominis). A midline incisional hernia is caused by a disruption of the linea alba, which in turn leads to unopposed contraction of the lateral abdominal wall muscles. It is this constant unopposed pull from the lateral muscles in combination with intraperitoneal pressure that leads to the gradual increase in size of these hernias and ultimately loss of abdominal domain. The position of the arcuate line is also important to understand. The arcuate line lies approximately three fourths of the way from the pubis to the umbilicus, or to use a bony anatomic landmark, approximately 2 cm cephalad to a line drawn between the two anterior superior iliac spines. Below this line there is no posterior rectus sheath (Cunningham, 2004). There is also a small triangular muscle called the pyrimidalis that overlies the most inferior portion of the rectus muscles just as they attach onto the pubis. This muscle is not relevant clinically.

2 Preoperative Considerations

The preoperative evaluation should include a complete medical history that includes any operative reports from previous operations. In cases where there have been previous hernia repairs, it is important to know what type of mesh repairs have been done, including the specific brand of mesh and the plane in which the mesh was placed and whether or not a component separation has been previously attempted. It should be noted in the history whether or not there were wound complications or infections after any of the previous operations.

It should be noted that in many circumstances, although patients can be quite miserable, incisional hernia repairs can be categorized as elective surgery. Those patients with hernia defects with a very wide base are at a low risk for bowel strangulation and obstruction. In patients like this, with non–life-threatening hernias, where the extent of their comorbidities carry an unacceptably high mortality risk, surgery should be avoided. One particular comorbidity, that of being super-obese (body mass index [BMI] >45), in addition to other general morbidities, carries a very high risk of hernia recurrence, reported to be as high as 50% (Vargo, 2008). In these patients, the risk-to-benefit scale is certainly tilted toward risk, and a serious effort at weight loss should be attempted before opting for elective surgery.

3 Operative Steps

Once the fascia is identified, undermining should continue until the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis is identified. This often can be visualized; however, a better way to find it is to pinch the abdominal wall musculature by placing the hand and fingers intraperitoneally with the thumb above the fascia and feeling for the thickening of the edge of the rectus muscle while the hand is slid medially. Some descriptions of open component separation describe continuing to undermine the skin all the way to the anterior axillary line. In my opinion this is not necessary and only leads to more risk for wound complications. I believe the undermining of the skin should end just at the point of where the external oblique fascia is divided.

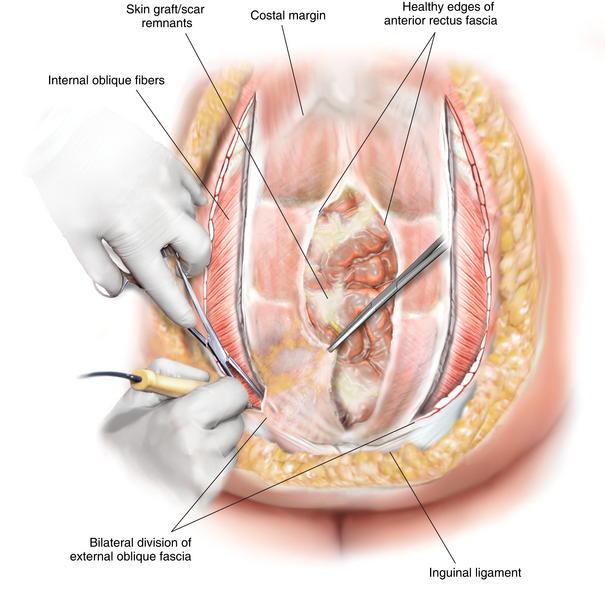

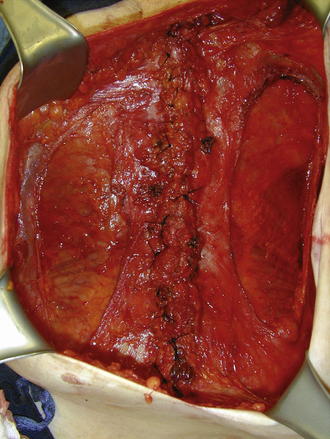

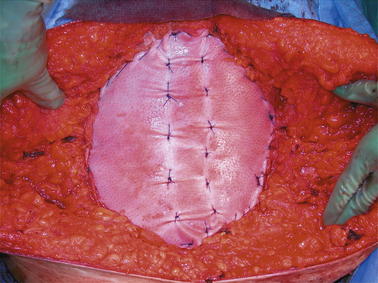

A small nick in the external oblique fascia should then be made just 1 cm lateral to the lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle. If the surgeon notices that there are still vertically oriented muscle fibers under the fascia, then the nick has been made too medial and another nick should be made a centimeter or so more laterally. Once the incision in the external oblique fascia is made, it is important to carry this incision all the way to just below the hernia defect (stopping short of the inguinal ligament) and all the way up over the costal margin superiorly. Generally, when going over the costal margin, the surgeon is dividing not only the fascial aponeurosis, but the actual muscle fibers of the external oblique muscle itself. It is important to completely transect these external oblique muscle fibers high up at the level of the costal margin. This allows for a much easier closure in the epigastric area. Figure 8-1 shows the division of the external oblique fascia just lateral to the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle. Figure 8-2 is an intraoperative photograph showing the division of the external oblique fascia. In this photo, the rectus abdominis muscles have already been sutured together.

In those cases where the rectus muscles will come together in the midline, I then proceed with performing a running closure with a #1 size loop suture made of monofilament slowly resorbable material (polydioxanone). In those situations where the fascial edges do not come together (which occurs less than 15% of the time in my practice), then a fascial bridge must be performed with some sort of mesh placed as an underlay. In this circumstance, the mesh must be placed in the intraperitoneal position, underneath the fascia and all the way to approximately the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis. Synthetic mesh should be avoided in circumstances where there is bacterial contamination or infection and also in those patients where comorbidities put the patient at an unacceptably high risk for developing a surgical site infection or wound breakdown. For those patients where synthetic mesh is undesirable, a biologic material should be used. It is important to note that there is a large and at times overwhelming variety of synthetic and biologic materials available to surgeons today, many of which have little in the way of data to support their use. Surgeons should obviously base their decision for material selection on the best available data at the time of use.

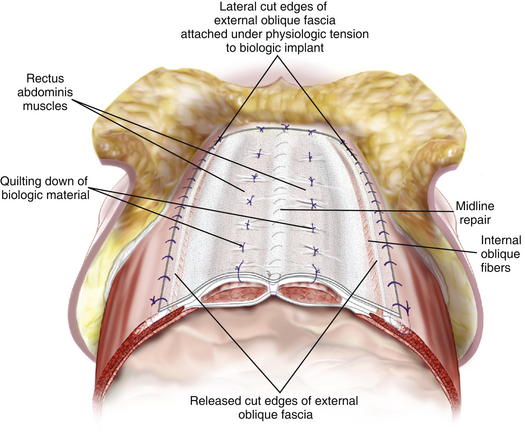

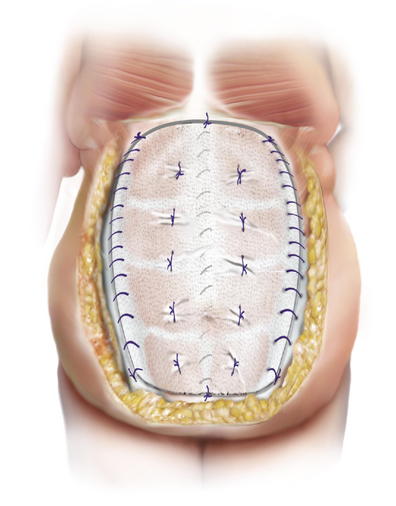

When the muscles do reach together in the midline, and are able to be closed primarily, a reinforcing material (synthetic or biologic as discussed in the previous paragraph) should be placed either as an underlay or as an overlay to reduce the risk for recurrence. It is my preference to place the material as an overlay. I prefer the overlay because it allows me to reinforce not only the midline repair, but the lateral areas of the abdominal wall where the external oblique has been divided. I run the material along the cut lateral free edge of the external oblique fascia. I then pull the material taught across the midline and suture it with another running suture to the cut lateral edge of the opposite external oblique fascia under physiologic tension. It is important that this be under some tension and not completely loose so that it will off-load some of the tension on the midline repair. This added layer reinforces not only the midline but also the two lateral areas where the external oblique has been cut. Furthermore, by placing the material under some tension it re-medializes the two external oblique muscles that otherwise retract laterally and become useless. By effectively reinserting the two external muscles across the midline to one another it allows these muscles to continue to act as functional muscle units. It is important to quilt the material down to the anterior abdominal wall (Figs. 8-3, 8-4, and 8-5). This is done with size 0 polydioxanone suture. These quilting sutures must be placed only over the top of the rectus abdominis muscles because they are placed in a blind fashion. The needle is placed through the onlay material, then placed in a skiving fashion through the anterior rectus fascia and then brought back up through the implant material. This is safe as long as the rectus muscle is present. Laterally, the abdominal wall may be too thin to safely place these sutures without risk of entering the peritoneal space. The quilting sutures are important to place because they further offload tension from the midline by further distributing the tension and they prevent seroma formation between the implant material and the fascia, allowing vascular ingrowth into the material more readily. Our group has recently reported a 7% recurrence rate with a mean follow-up of 1 year in 60 consecutive patients using this technique (Stromberg, 2010).

A final maneuver that has helped with wound breakdown in my practice is the use of negative pressure therapy over the top of my closed incision. I perform an intradermal or subcuticular closure with resorbable sutures and then place a nonadherent porous dressing over the top of the suture line. On top of that I place the foam and the adhesive layer and place the dressing on negative 125 mm Hg suction. This dressing draws away any drainage from the suture line, but more importantly, it draws blood flow to the wound edges and reduces edema while mechanically pulling together the skin edges and stabilizing the suture line. This dressing is left in place for the patient’s entire hospitalization (up to 8 days). This has remarkably improved outcomes in even the most challenging large panniculectomy incisions.

Cunningham S.C., Rosson G.D., Lee R.H., Williams J.Z., Justman C., Slezak S., Goldberg N.H., Silverman R.P. Localization of the arcuate line from surface anatomic landmarks: a cadaveric study. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 53(2), August 2004.

Stromberg J., Hamidi R., Silverman R.P., Singh D. Abdominal wall reconstruction with component separation and porcine acellular dermal matrix onlay. 2010 Plastic Surgery Research Council; May 23-26, 2010.

Vargo D.J. long term follow up of human acellular dermal matrix in 100 patients with complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Hernia Update 2008. American Hernia Society; March 12-16, 2008. P 262