Oophorectomy for Benign and Malignant Conditions

Anatomy and Dissection of the Adnexa

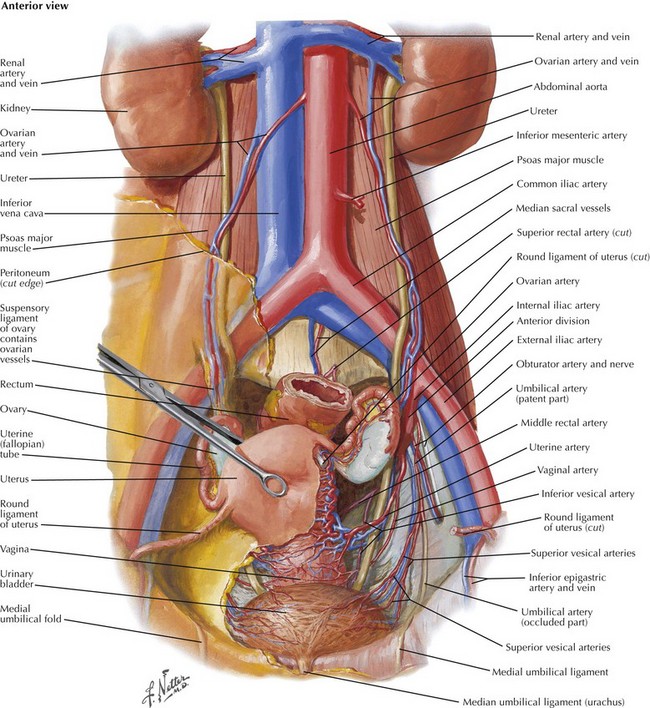

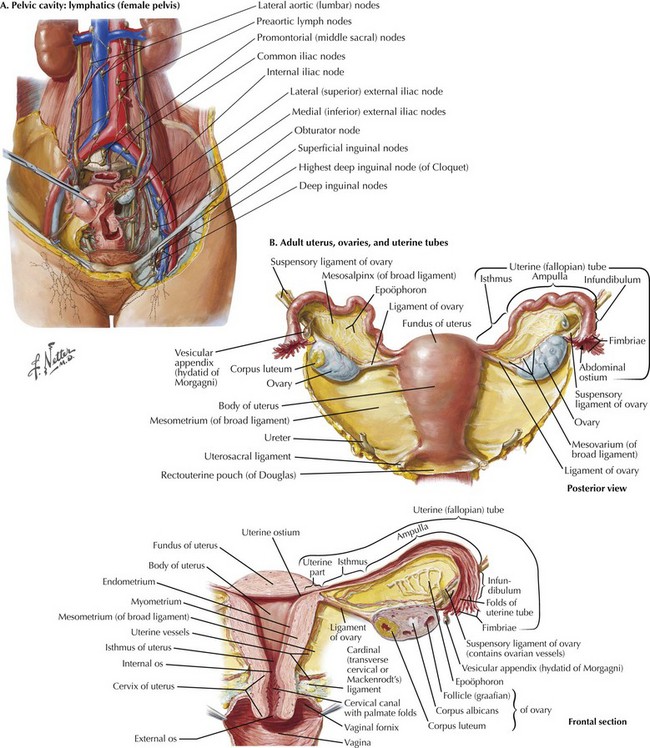

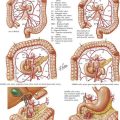

The adnexa refers to both the ovary and fallopian tube. An intimate understanding of the vascular supply to the adnexa and the relationship to the underlying ureter and uterus is required before commencing surgery (Fig. 52-1). The general principles are similar regardless of surgical approach (open, laparoscopic, or robotic).

Gonadal Vessels and Infundibulopelvic Ligament

The best approach to removing a pelvic mass is first to open the retroperitoneum and identify the gonadal vessels and ureter. The gonadal blood supply, or infundibulopelvic ligament (IP), originates from the aorta and runs parallel to the ureter, crossing into the pelvis over the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels (Fig. 52-2, A).

The IP can then be isolated, clamped, and cut, with the ureter under direct visualization. The adnexa can be elevated out of the pelvis and its peritoneal attachments mobilized until reaching its attachment to the uterus, the utero-ovarian pedicle (Fig. 52-2, B).

Large Masses and Modified Approaches

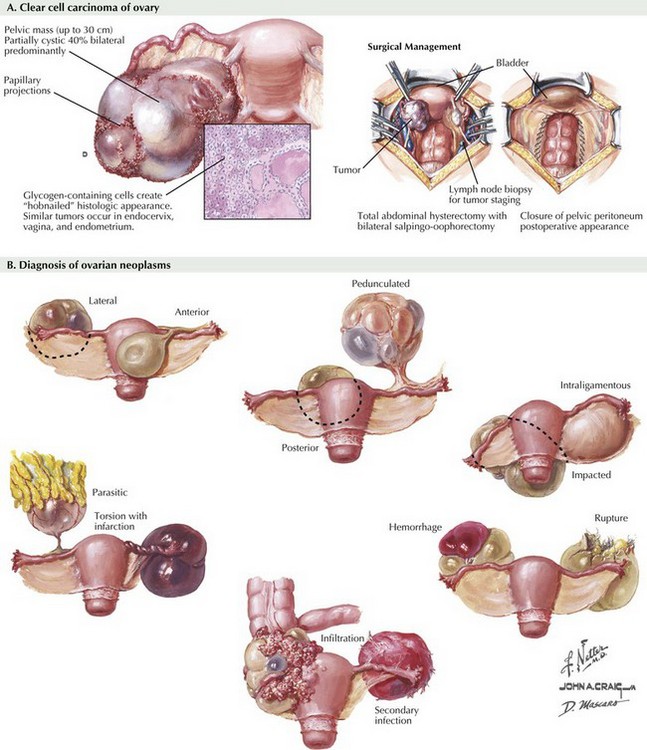

Unfortunately, some ovarian tumors can routinely grow to be greater than 20 or 30 cm before they are identified. In these cases, it may not be possible to isolate the blood supply and identify the ureter before removing the mass itself (Fig. 52-3, A).

In some cases, neither the IP nor the utero-ovarian pedicle can be identified, and the mass itself can often be delivered through the incision and the adnexa itself clamped. In the author’s experience, there is little chance of inadvertently injuring the ureter because it runs deep to the IP pedicle (Fig. 52-3, B).

Radical Oophorectomy

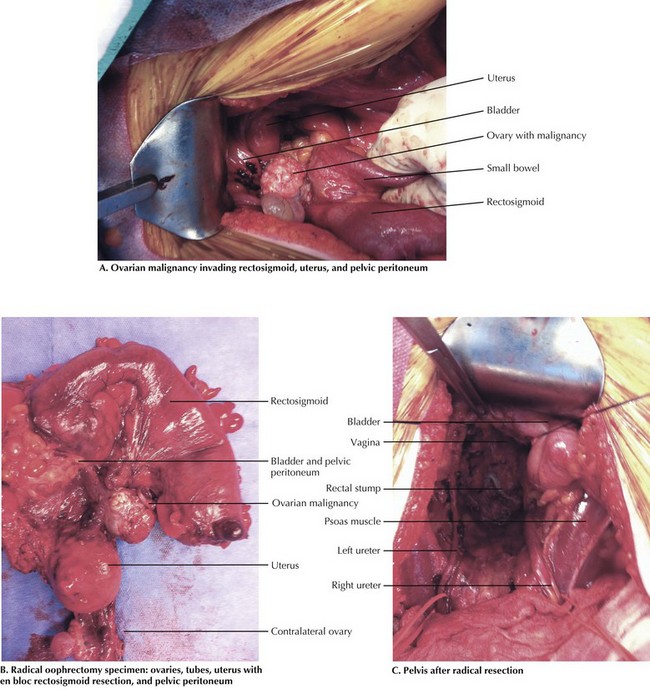

The resection of the adnexa in these patients starts in the upper abdomen at or near the origin of the gonadal blood supply. Generally, the white line of Toldt is developed bilaterally and the abdominal ureter and gonadal blood supply identified. It may be helpful to isolate the ureters at this point on vessel loops to keep them under continuous surveillance. Gentle tension facilitates the dissection. The gonadal vessels can be sacrificed at their origin or anywhere along their abdominal path. In the setting of an ovarian malignancy, the peritoneum overlying the gutters is incorporated along with this pedicle and taken en bloc into the pelvis, incorporating any extrapelvic disease (Fig. 52-4, A).

This peritoneum is contiguous with the peritoneum overlying the uterus. Advanced ovarian malignancy disease almost always involves the posterior pelvic peritoneum and sigmoid mesentery, requiring rectosigmoid resection to eradicate the disease completely. Once the sigmoid is transected, the retroperitoneal dissection is carried laterally to encompass the anterior dissection and posteriorly along the sacrum. Similar to a colorectal malignancy, the dissection continues behind the rectum in the plane between the peritoneum and mesorectum (Fig. 52-4, B).

At this point, the adnexal structures are completely incorporated in the surgical specimen. The procedure is completed by isolating the uterine arteries, either at their origins or just medial to where they cross the ureters. Dissection is carried down along the cervix until the cervicovaginal refection is identified. A colpotomy is performed and the rectovaginal septum developed. The rectum can then be transected with a stapling device and the specimen removed (Fig. 52-4, C).

Alcázar, JL, Royo, P, Jurado, M, et al. Triage for surgical management of ovarian tumors in asymptomatic women: assessment of an ultrasound-based scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(2):220–225.

Chang, SJ, Bristow, RE. Evolution of surgical treatment paradigms for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: redefining “optimal” residual disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(2):483–492.

Esselen, KM, Rodriguez, N, Growdon, W, et al. Patterns of recurrence in advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers treated with intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1):51–54.

Giuntoli, RL, 2nd., Vang, RS, Bristow, RE. Evaluation and management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(3):492–505.

Moore, RG, Miller, MC, Disilvestro, P, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm in women with a pelvic mass. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):280–288.