6

Oncoplastic procedures to allow breast conservation and a satisfactory cosmetic outcome

Part 1

Volume replacement techniques to improve cosmetic outcomes after breast-conserving surgery

Introduction

The risk of LR is related to a number of factors, including positive margins, tumour grade, extent of in situ component, lymphovascular invasion and age. Whole-breast section analysis techniques have been used to show the likelihood of complete excision of unicentric carcinomas using different margins of excision (see Chapters 4 and 15).

Local recurrence and cosmetic outcome

The margins of clearance and to a lesser degree the extent of local excision during BCS are strong predictors of subsequent LR.6

The extent of local excision remains a controversial issue in BCS. The wider the margin of clearance, the less the risk of incomplete excision and thus potentially of LR (Table 6.1), but the greater the amount of tissue removed, the higher the risk of visible deformity leading to an unacceptable cosmetic result. This clash of interests8 is most evident when attempting BCS in patients with smaller breast–tumour ratios, for example when planning BCS for a 10-mm tumour in a 200-g breast or a 5-cm tumour in a 700-g breast.

Table 6.1

Technique-related outcomes of breast-conserving surgery

| Quadrantectomy | Wide local excision | |

| Margin (cm) | 2–4 | 1–2 |

| Clearance (%)* | < 90 | < 58 |

| Recurrence (%)† | 2 | 7 |

| Cosmesis | Fair | Good |

The chances of a poor cosmetic outcome are increased still further when the tumour is in a central, medial or inferior location.9,10 Cosmetic failure is more common than generally appreciated, occurring in up to 50% of patients after BCS.11–15 A number of factors are responsible, including volume loss of more than 10–20% leading to retraction and asymmetry, nipple–areola displacement or distortion, the use of ugly and inappropriate incisions, and the local effects of radiotherapy. Volume loss underlies many of the most visible and distressing examples of poor cosmetic outcome and the effects may be compounded by associated displacement of the nipple–areola complex (NAC). Poor surgical technique leading to postoperative haematoma, infection or breast tissue and fat necrosis will increase the amount of scarring and retraction, and add to the risks of deformity. Moreover, the use of suction drains, inappropriate incisions and en bloc resections can worsen the cosmetic result still further.

Role of oncoplastic surgery

1. Oncoplastic techniques allow wider excision of breast cancers without risking major local deformity.

2. The use of oncoplastic techniques to prevent deformity can extend the scope of BCS to include patients with 3–5 cm tumours, without compromising the adequacy of resection or the cosmetic outcome.

3. Volume replacement can be used after previous BCS and radiotherapy to correct unacceptable deformity16 and may prevent the need for mastectomy in some cases of local recurrence when further local excision would result in considerable volume loss.

Choice of oncoplastic technique

The choice of technique depends on a number of factors, including the extent of resection, position of the tumour, timing of surgery, experience of the surgeon and expectations of the patient. Reconstruction at the same time as resection (breast-sparing reconstruction) is gaining in popularity. As a general rule, it is much easier to prevent than to correct a deformity that has developed as the sequela of previous surgery. Immediate reconstruction at the time of mastectomy is associated with clear surgical,17 financial18,19 and psychological20 benefits, and similar benefits are seen in patients undergoing immediate breast-sparing reconstruction after partial mastectomy.

Resection defects can be reconstructed in one of two ways: (i) by volume replacement, importing volume from elsewhere to replace the amount of tissue resected; or (ii) by volume displacement, recruiting and transposing local dermoglandular flaps into the resection site. Volume replacement techniques can restore the shape and size of the breast, achieving symmetry and excellent cosmetic results without the need for contralateral surgery. However, these techniques require additional theatre time and may be complicated by donor-site morbidity, flap loss and an extended convalescence. In contrast, volume displacement techniques require less extensive surgery, can limit scars on the breast and limit donor-site problems. These procedures may be complicated by necrosis of the dermoglandular flaps and contralateral surgery is usually required to restore symmetry as volume loss is inevitable (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

Comparison of techniques for breast-conserving reconstruction

| Volume replacement | Volume displacement | |

| Symmetry | Good | Variable |

| Scars | Breast + back | Periareolar inverted-T |

| Problems | Donor scar Seroma flap loss |

Parenchymal necrosis Nipple necrosis Volume loss |

| Theatre time (hours) | 2–3 | 1–2 (per side) |

| Convalescence (weeks) | 4–6 | 1–2 |

| Timing | Immediate or delayed | Immediate > delayed |

| Mammographic surveillance | Possibly enhanced | Unaffected |

Volume replacement techniques

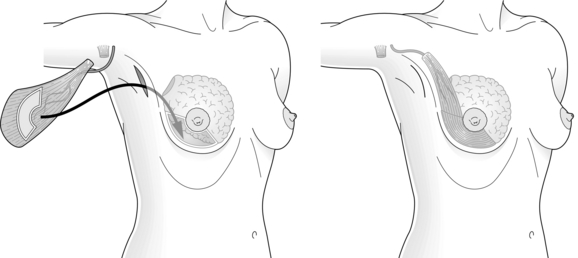

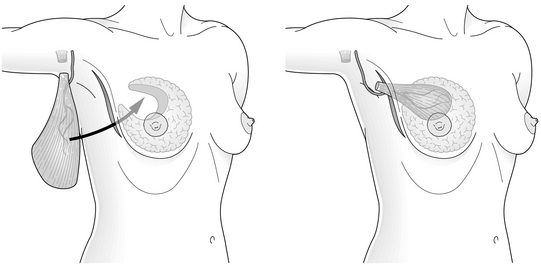

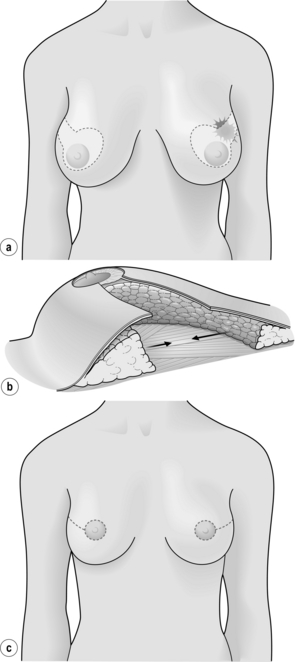

The myocutaneous LD flap carries a skin paddle that can be used to replace skin which has been resected at the time of BCS or as a result of contracture and scarring following previous resection and radiotherapy16 (Fig. 6.1). Although the skin paddle adds to the replacement volume, it can lead to an ugly ‘patch’ effect because of the difference in colour between the donor skin and the skin of the native breast.

Perforator flaps22,23 based on thoracodorsal artery perforators (‘TDAP flaps’) and lateral intercostal artery perforators (‘LICAP flaps’) are gaining popularity. They provide skin and subcutaneous fat for volume replacement, are relatively quick to perform, and appear to be associated with a faster recovery and less morbidity than LD flaps. As the LD is relatively undisturbed, the LD muscle can be used for breast reconstruction if a mastectomy is required for a subsequent local recurrence. TDAP flaps are most suitable for lateral and upper pole defects, while LICAP flaps can be used to reconstruct small to medium-sized lateral pole defects. Neither flap can be transposed sufficiently to reconstruct medial pole defects, which are more suitable for reconstruction by an LD miniflap that has been fully mobilised following divison of the tendon, all the serratus anterior branches of the vessels and all remaining fascial attachments to terres major. Other flaps, such as the lateral thoracic adipose tissue flap, have been described24 but their clinical utility is unclear.

Lipomodelling techniques25 have been used to correct rather than to prevent deformity after BCS.26 Stem cells harvested from fat are injected around the defect, into underlying pectoralis muscle and overlying subcutaneous fat, avoiding the breast parenchyma. This helps to avoid the confusing mammographic images resulting from areas of calcified fat necrosis in the vicinity of the tumour bed. The theoretical risk of tumour induction by injected stem cells remains a concern, and has led to the somewhat cautious introduction of this innovative technique into clinical practice.26 Some surgeons have started to use lipomodelling at the same time as wide local excision but no long-term results of this technique have yet been reported.

Non-autologous volume replacement with saline or silicone implants has been tried with mixed success.27,28 Implants can be placed directly into the resection defect or under pectoralis major. They cannot be moulded to fit the resection defect and they form localised capsules, particularly in irradiated tissues. This may interfere with clinical examination and also mammographic surveillance, although there are techniques to allow mammaplasty in breasts with implants and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up is an option in such patients. If using implants, low height and low projection implants placed low in the treated breast combined with lipomodelling gives the best results. If there is deformity and significant nipple deviation then a myocutaneous flap is preferred. Autologous tissue transfer is usually the best option for most patients and results in a lifelike breast of normal shape and size.

1. Resection through a radial incision and LD harvest through an axillary incision.29

2. Conventional LD myocutaneous flap harvest for correction of major resection defects.16

3. Resection through a circumferential incision and endoscopic LD flap harvest and reconstruction through an axillary incision.30

4. Resection, LD harvest and reconstruction through a single lateral incision.21

Indications for volume replacement

Breast conservation with or without reconstruction was formerly reserved for patients with unifocal tumours, but the much wider excision achieved in patients undergoing immediate volume replacement allows resection of multifocal disease with clear margins and excellent local control.33 Volume replacement may be inappropriate in those with more widespread disease or locally advanced T4 tumours. Likewise, LD volume replacement is hazardous in patients with a history suggesting damage to the thoracodorsal pedicle or to the LD muscle, and alternative methods should be considered (Box 6.1). Patients should be informed that using LD for breast conservation precludes its subsequent use for later breast reconstruction. If a mastectomy is required to treat recurrent disease, the options include a variety of free flaps or subpectoral implant-based reconstruction.

Timing of procedures

Immediate reconstruction can be carried out as a one-stage procedure,21,34 which involves simultaneous resection and correction of the resulting defect. This requires perioperative confirmation of complete tumour excision using frozen-section techniques. As an alternative, the procedure can be split into two steps.35 The first step involves excising the cancer and performing a sentinel node biopsy if the nodes are clinically and radiologically normal and the second step includes axillary dissection if required, flap harvest and reconstruction, and is carried out a few days later after confirmation of clear tumour resection margins. Patients undergoing a one-stage procedure must be informed that a mastectomy with or without reconstruction may be required if subsequent histopathological analysis confirms incomplete tumour excision.

Volume replacement with latissimus dorsi miniflaps

There are many similarities between the different surgical approaches used in breast-conserving reconstruction and these can be best illustrated by summarising the main steps involved in LD miniflap reconstruction, which has been described in detail elsewhere.36,37 This procedure involves the use of a myosubcutaneous flap of LD for immediate reconstruction of a partial mastectomy defect, most commonly in the central zone but also in the upper outer and upper inner quadrants of the breast. The term ‘miniflap’ is somewhat misleading, as the flap needs to be of sufficient volume to replace resection defects resulting from the excision of 150–350 g of breast tissue. Moreover, the miniflap needs to be bulky enough to allow for a small degree of postoperative flap atrophy.

Perioperative outcomes

The time required for breast-conserving immediate reconstruction with a miniflap lies somewhere between BCS alone and total mastectomy combined with immediate LD reconstruction. Early postoperative complications include infection, flap necrosis, haematoma formation and transient brachial plexopathy,34 although postoperative stay and disability are similar to other types of BCS. Breast oedema is common, particularly after extensive resection, but usually settles within 6–8 weeks. It may be caused by division of multiple afferent lymphatic pathways during retromammary dissection. Donor-site seroma formation occurs in almost all patients, and can be reduced by ‘quilting’ or delaying drain removal. Flap necrosis is rare, and can be avoided by gentle resection and handling of the pedicle and by taking care to prevent traction and twisting injuries during transposition and fixation of the flap after tendon division.

Late sequelae of volume replacement include lateral retraction of the flap, leading to distortion and hollowing of the resection site, and flap atrophy. Flap retraction can be avoided by division and fixation of the tendon and careful suture of the flap into the resection defect. Detectable flap atrophy occurs in a minority of patients followed for up to 10 years.38 It can be counteracted by over-replacement of the resected volume with a fully innervated flap that has been harvested with a generous layer of subcutaneous fat, by using a myocutaneous flap or by later lipofilling.16

Frozen-section analysis of bed biopsies has been found to correlate closely with the adequacy of excision determined by formal histopathology.33 Moreover, the use of LD miniflap reconstruction leads to a significant fall in the number of incomplete excisions compared with BCS alone24 without compromising the cosmetic outcome. Sensory loss following miniflap reconstruction is minimal compared with the loss following total mastectomy.39 The sensory innervation of the breast and NAC is largely intact, except over the resected quadrant. Finally, volume replacement preserves symmetry, avoiding the need for alterations to the contralateral breast in almost all patients (Fig. 6.3).

Mammographic surveillance

The mammographic appearance of the partially reconstructed breast compares favourably with the appearances after routine BCS. Symmetry is preserved and the fibres of the isodense flap may be detectable, often associated with a variable zone of radiolucency that corresponds to the layer of surface fat. Flaps may be indistinguishable from the surrounding breast tissue, and important radiological characteristics such as skin thickening, stellate lesions and microcalcifications are easily visualised after flap transfer. Volume replacement does not compromise the early detection of LR,40 which typically develops at the junctional zone between muscle and breast parenchyma. The appearance of miniflap on mammograms contrasts with the radiodense distorting stellate scars that are a common source of diagnostic confusion following conventional BCS. Lastly, very few patients develop clinically detectable flap atrophy, with the majority of flaps remaining bulky and functional throughout the period of follow-up.

Future prospects

The role of breast-conserving volume replacement is set to increase as more precise, image-guided resection of specific zones of breast tissue becomes possible. Increasingly sophisticated imaging techniques, such as high-frequency ultrasound and contrast-enhanced dynamic magnetic resonance imaging,41 may in future enable exact delineation and excision of all malignant and premalignant changes. Endoscopically assisted techniques42 may increase the ability to harvest more bulky myosubcutaneous flaps, allowing the reconstruction of more extensive resection defects. This will require the further development of novel techniques for endoscopic dissection,30 including the use of balloon-assisted techniques42,43 and carbon dioxide insufflation to maintain the epimuscular optical cavities. Current progress is hampered by the use of non-flexible straight endoscopes to carry out dissection over the rigid convex surface of the chest wall.

Deformities following breast-conserving surgery

In order to better assess the surgical approach for these patients, a classification of the cosmetic sequelae after BCS has been published by Clough et al.44,45 This simple classification defines three groups of patients based on clinical examination (Fig. 6.4). The advantage of this classification is that it is a valuable guide for choosing the optimal reconstructive technique, but it is also a good predictor of the final cosmetic result after surgery.

Figure 6.4 Deformities after conservative treatment of breast cancer. (a) Type I: a symmetrical breast with no deformity of the treated breast. (b) Type II: deformity of the treated breast, compatible with partial reconstruction and breast conservation. (c) Type III: major deformity of the breast requiring mastectomy. Reproduced from Clough KB, Claude N, Fitoussi A et al. Oncoplastic conservative surgery for breast cancer. In: Operative techniques in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999; pp. 50–60. With permission from Elsevier.

Poor remodelling is one of the reasons for an ugly deformity after lumpectomy or quadrantectomy.46,47 Some surgeons perform no remodelling at all, leaving an empty defect and relying on a postoperative haematoma to fill the dead space. This may produce acceptable results in the short term but breast retraction of larger defects invariably occurs with longer follow-up, leading to major deformities that are increased by postoperative radiotherapy.10,44,48,49

References

1. Fisher, B., Redmond, C., Posson, R., et al, Eight-year results of a randomised clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and lumpectomy with or without irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1989; 320:822–828. 2927449 A seminal trial (NSABP B-06) showing equivalent overall survival in patients with breast cancer treated either by mastectomy or by lumpectomy and radiotherapy.

2. Veronesi, U., Saccozzi, R., Del Vecchio, M., et al, Comparing radical mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection and radiotherapy in patients with small cancers of the breast. N Engl J Med 1981; 305:6–11. 7015141 A seminal trial comparing the treatment of patients with breast cancer by radical mastectomy or quadrantectomy, showing equivalent overall survival in each group.

3. Veronesi, U., Banfi, A., Del Vecchio, M., et al, Comparison of Halsted mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection, and radiotherapy in early breast cancer: long-term results. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1986; 22:1085–1089. 3536526 A seminal trial comparing the treatment of patients with breast cancer by radical mastectomy or quadrantectomy, showing equivalent overall survival in each group after long-term follow-up.

4. Abrams, J., Chen, T., Giusti, R., Survival after breast-sparing surgery versus mastectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994; 86:1672–1673. 7966392

5. Holland, R., Veling, S.H., Mravunac, M., et al, Histologic multifocality of TIS, T1–2 breast-carcinomas: implications for clinical trials of breast-conserving surgery. Cancer 1985; 56:979–990. 2990668 A detailed study using serial whole-breast sections to establish the distribution of breast malignancy in relation to the margin of the reference tumour.

6. Dixon, J. Histological factors predicting breast recurrence following breast-conserving therapy. Breast. 1993; 2:197.

7. Veronesi, U., Voltarrani, F., Luini, A., et al, Quadrantectomy versus lumpectomy for small size breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 1990; 26:671–673. 2144153 A seminal trial comparing very wide local excision (quadrantectomy) with limited excision of breast carcinoma (lumpectomy). Quadrantectomy was associated with significantly lower rates of local recurrence when compared with lumpectomy.

8. Audretsch, W.P. Reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect: classification and method. In: Spear S.L., ed. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:155–195.

9. Pearl, R.M., Wisnicki, J., Breast reconstruction following lumpectomy and irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985; 76:83–86. 2989962

10. Berrino, P., Campora, E., Sauti, P., Postquadrantectomy breast deformities: classification and techniques of surgical correction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1987; 79:567–572. 3823249

11. Borger, J.H., Keijser, A.H., Conservative breast cancer treatment: analysis of cosmetic role and the role of concomitant adjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1987; 13:1173–1177. 3610704

12. Van Limbergen, E., Rijnders, A., van der Schueren, E., et al, Cosmetic evaluation of conserving treatment for mammary cancer. 2. A quantitative analysis of the influence of radiation dose, fractionation schedules and surgical treatment techniques on cosmetic results. Radiother Oncol 1989; 16:253–267. 2616812

13. Van Limbergen, E., Van der Schueren, E., Van Tongelen, K., Cosmetic evaluation of breast conserving treatment for mammary cancer. 1. Proposal of quantitative scoring system. Radiother Oncol 1989; 16:159–167. 2587807

14. Olivotto, I.A., Rose, M.A., Osteen, R.J., et al, Late cosmetic outcome after conservative surgery and radiotherapy: analysis of causes of cosmetic failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989; 17:747–753. 2777664

15. Ray, G.R., Fish, B.J., Marmor, J.B., et al, Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on cosmesis and complications in stages 1 and 2 carcinoma of the breast treated by biopsy and radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1984; 10:837–841. 6429099

16. Slavin, S.A., Love, S.M., Sadowsky, N.L., Reconstruction of the irradiated partial mastectomy defect with autogenous tissues. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 90:854–865. 1410039

17. O’Brien, W., Hasselgren, P.-O., Hummel, R.P., et al, Comparison of postoperative wound complications in early cancer recurrence between patients undergoing mastectomy with or without immediate breast reconstruction. Am J Surg 1993; 166:1–5. 8392300

18. Eberlein, T.J., Crespo, L.D., Smith, B.L., et al, Prospective evaluation of immediate reconstruction after mastectomy. Ann Surg 1993; 218:29–36. 8328826

19. Elkowitz, A., Colen, S., Slavin, S., et al, Various methods of breast reconstruction after mastectomy: an economic comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993; 92:77–83. 8516410

20. Dean, C., Chetty, U., Forrest, A.P.M., Effect of immediate breast reconstruction on psychosocial morbidity after mastectomy. Lancet 1983; i:459–462. 6131178

21. Raja, M.A.K., Straker, V.F., Rainsbury, R.M., Extending the role of breast-conserving surgery by immediate volume replacement. Br J Surg 1997; 84:101–105. 9043470

22. Hamdi, M., Van Landuyt, K., Hijjawi, J.B., et al, Surgical technique in pedicled thoracodorsal artery perforator flaps: a clinical experience with 99 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121:1632–1641. 18453987

23. Hamdi, M., Spano, A., Van Landuyt, K., et al, The lateral intercostal perforators: anatomical study and clinical application in breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121:389–396. 18300954

24. Ohuchi, N., Harada, Y., Ishida, T., et al, Breast-conserving surgery for primary breast cancer; immediate volume replacement using lateral tissue flap. Breast Cancer 1997; 4:135–141. 11091588

25. Coleman, S.R., Saboeiro, A.P., Fat grafting for the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 119:775–785. 17312477

26. Chan, C.W., McCulley, S.J., Macmillan, R.D., Autologous fat transfer – a review of the literature with a focus on breast cancer surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008; 61:1438–1448. 18848513

27. Schaverien, M.V., Stutchfield, B.M., Raine, C., et al, Implant-based augmentation mammaplasty following breast conservation surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69(3):240–243 Feb 21. Epub ahead of print. 21346535

28. Elton, C., Jones, P.A., Initial experience of intramammary prostheses in breast conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 1999; 25:138–141. 10218454

29. Noguchi, M., Taniya, T., Miyasaki, I., et al, Immediate transposition of a latissimus dorsi muscle for correcting a post quadrantectomy breast deformity in Japanese patients. Int Surg 1990; 75:166–170. 2242969

30. Eaves, F.F., Bostwick, J., Nahai, F., et al, Endoscopic techniques in aesthetic breast surgery. Clin Plast Surg 1995; 22:683–695. 8846636

31. Cochrane, R., Valasiadou, P., Wilson, A., et al, Cosmesis and satisfaction after breast conserving surgery correlates with the percentage of breast volume excised. Br J Surg 2003; 90:1505–1509. 14648728

32. Al-Ghazal, S.K., Fallowfield, L., Blamey, R.W., Does cosmetic outcome from treatment of pimary breast cancer influence psychological morbidity? Eur J Surg Oncol 1999; 25:571–573. 10556001

33. Rusby, J., Paramanathan, N., Laws, S., et al, Immediate miniflap volume replacement for partial mastectomy: use of intraoperative frozen sections to confirm negative margins. Am J Surg 2008; 196:512–518. 18809053

34. Rainsbury, R.M., Paramanathan, N., Recent progress with breast-conserving volume replacement using latissimus dorsi miniflaps in UK patients. Breast Cancer 1998; 5:139–147. 11091639

35. Dixon, J.M., Venizelos, B., Chan, P., Latissimus dorsi miniflap: a technique for extending breast conservation. Breast 2002; 11:58–65. 14965647

36. Rainsbury, R.M., Breast-sparing reconstruction with latissimus dorsi miniflaps. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002; 28:891–895. 12477482

37. Rainsbury, R.M. The mini latissimus dorsi flap. In: Querci della Rovere G., Benson J.R., Nava M., eds. Oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery of the breast. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2011:96–104.

38. Laws, S.A.M., Cheetham, J.E., Rainsbury, R.M. Temporal changes in breast volume after surgery for breast cancer and the implications for volume replacement with the latissimus dorsi miniflap. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001; 27:790.

39. Gendy, R.K., Able, J.A., Rainsbury, R.M., Impact of skinsparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and breast-sparing reconstruction with miniflaps on the outcomes of oncoplastic breast surgery. Br J Surg 2003; 90:433–439. 12673744

40. Monticciolo, D.L., Ross, D., Bostwick, J., et al, Autogenous breast reconstruction with endoscopic latissimus dorsi with musculo-subcutaneous flaps in patients choosing breast-conserving therapy: mammographic appearance. Am J Radiol 1996; 167:385–389. 8686611

41. Gilles, R., Guinebretiere, J.-M. Magnetic resonance imaging. In: Silverstein M.J., ed. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997:159–166.

42. Bass, L.S., Karp, N.S., Benacquista, T., et al, Endoscopic harvest of the rectus abdominus free flap: balloon dissection in the fascial plain. Ann Plast Surg 1995; 34:274–279. 7598384

43. Van Buskark, E.R., Krehnke, R.D., Montgomery, R.L., et al, Endoscopic harvest of the latissimus dorsi muscle using balloon dissection technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 99:899–903. 9047218

44. Clough, K.B., Cuminet, J., Fitoussi, A., et al, Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: classification and results of surgical correction. Ann Plast Surg 1998; 41:471–481. 9827948 The original classification of types of deformity following partial mastectomy and the use of therapeutic mammaplasty to avoid rather than correct deformity.

45. Clough, K.B., Thomas, S.S., Fitoussi, A.D., et al, Reconstruction after conservative treatment for breast cancer: cosmetic sequelae classification revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(7):1743–1753. 15577344

46. Petit, J.-Y., Rigault, L., Zekri, A., et al, Poor esthetic results after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Techniques of partial breast reconstruction. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 1989; 34:103–108. 2472100

47. Rose, M.A., Olivotto, I.A., Cady, B., et al, Conservative surgery and radiation therapy for early breast cancer. Long-term cosmetic results. Arch Surg 1989; 124:153–157. 2916935

48. Berrino, P., Campora, E., Leone, S., et al, Correction of type II breast deformities following conservative cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 90:846–853. 1410038

49. Petit, J.-Y., Rietjens, M. Deformities following tumourectomy and partial mastectomy. In: Noone B., ed. Plastic and reconstruction surgery of the breast. Philadelphia: BC Decker, 1991.

50. Clough, K.B., Kroll, S., Audretsch, W., An approach to the repair of partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999; 104:409–420. 10654684 Pooled experience of breast-conserving reconstruction from France, USA and Germany using volume replacement and volume displacement techniques.

Part 2

Breast displacement techniques to increase resection volumes for breast-conserving surgery

Introduction

Oncoplastic surgery (OPS) has emerged as a new approach to allow wide excisions for BCS without compromising the natural shape of the breast. It is based upon integrating plastic surgery techniques with immediate reshaping of the breast together with oncological surgery to excise the breast cancer. The conceptual idea of OPS is not new and its oncological efficacy in terms of margin status and recurrence compares favourably to traditional BCS.1,2

Oncoplastic considerations

Selection criteria for oncoplasty

There are three elements that are important in the identification of patients who would benefit from an oncoplastic approach. The two factors already recognised as major indications for OPS are excision volume and tumour location.3 The third additional element is glandular density, a recently recognised factor in the determination of the safety of major breast reshaping. When considered together, these three major elements provide a sound basis for determining when and what type of OPS to perform and, more importantly, in reducing the guesswork when performing BCS.

Volume

Excision volume compared to the total breast volume is estimated preoperatively. Through systematic correlation of specimen weights compared with tumour size, an accurate preoperative estimation of excision volume can be achieved, once the tumour size is known from preoperative imaging. The average specimen from BCS should weigh between 20 and 40 g, and as a general rule 80 g of breast tissue is the maximum weight that can be removed from a medium-sized breast without resulting in deformity (see Chapter 4).

OPS techniques allow for significantly greater excision volumes while preserving the natural breast shape. Reshaping of the breast is based upon rearrangement of the breast parenchyma to create a homogeneous redistribution of volume loss. This redistribution can be achieved easily though either the advancement or rotation of breast tissue into excision defects. Another option is to harvest a latissimus dorsi ‘miniflap’ to fill in the lumpectomy cavity (see Part 1 of this chapter).3

Tumour location

One example is the ‘bird’s beak’ deformity that is classically seen during excision of tumours from the lower pole of the breast (Fig. 6.5a). Other examples of difficult areas include excision of a central tumour (Fig. 6.5b) and removal of cancers from the upper inner quadrant (Fig. 6.5c). Therefore, it is important when planning the appropriate surgical approach to determine the tumour location and the likely level of associated deformity. An oncoplastic atlas of surgical techniques based on tumour location has been developed. The atlas provides a specific surgical technique for each possible tumour location in the breast.

Glandular characteristics and breast density

Glandular density is evaluated both clinically and radiographically. Although clinical examination provides reliable information on density, mammographic evaluation is a more reproducible approach for breast density determination. Breast density predicts the amount of fat in the breast and determines the ability to perform extensive breast undermining and reshaping without complications. Breast density can be classified into four categories based on the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). The four categories comprise: (1) fatty; (2) scattered fibroglandular; (3) heterogeneously dense; or (4) extremely dense breast tissue.5

Classification system

Complexity of surgical procedure: a bi-level system

The bi-level classification system lends itself to the creation of a practical guide to OPS and provides the necessary framework during surgical planning to correctly select the most appropriate surgical procedure for the patient (Table 6.3).

Table 6.3

| Criteria | Level I | Level II |

| Maximum excision volume ratio | 20% | 20–50% |

| Requirement of skin excision for reshaping | No | Yes |

| Specific training in reduction and mam- maplasty techniques | No | Yes |

| Glandular characteristics | Dense | Dense or fatty |

Level I oncoplastic techniques

Incisions

In our experience, OPS is not minimally invasive surgery. The location of the incision is at the discretion of the operating surgeon. In general, incisions should allow for both en bloc excision of the cancer, without causing fragmentation of the specimen, and also allow undermining of the surrounding breast tissue to facilitate reshaping. The general principle for placing incisions is to follow Kraissl’s lines of maximum resting skin tension to limit visible scarring6 (see Chapter 4). However, in many cases an incision away from the cancer is possible, such as along the areola border with radial extension towards the tumour in the axilla for upper outer quadrant lesions, or in the inframammary fold for cancers in the lower half of the breast.

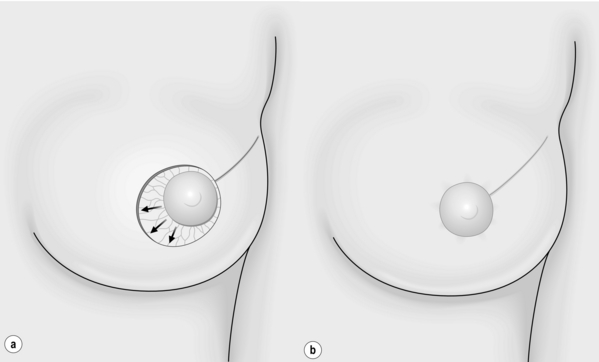

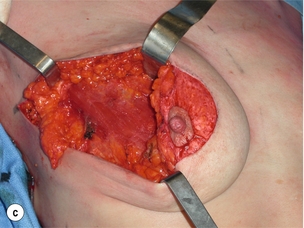

Skin undermining

Extensive subcutaneous undermining ranging from one-half to two-thirds of the breast envelope may be required to facilitate glandular redistribution after removal of the tumour (Fig. 6.6a). Aggressive undermining can free an entire quadrant from the overlying skin envelope. In terms of technique, it is easier to undermine a large area of skin before excising the lesion. Skin undermining should be performed in the plane between the breast tissue and subcutaneous fat and definition of this plan is enhanced by the use of hydrodissection using saline containing 1 in 500,000 to 1 in a million adrenaline (see Chapter 5).

Figure 6.6 Level I oncoplastic techniques: skin and NAC undermining. (a) Extensive skin undermining. (b) Wide excision from subcutaneous fat to muscle, then NAC undermining. (c) Glandular flap re-approximation.

Although smoking does not prevent the completion of a safe level I oncoplasty, it decreases the total area of skin that can be undermined safely. Patients who smoke should be warned of the greater risk of complications and advised to reduce or stop smoking for as long as possible before and immediately after surgery (see Chapter 5).

Nipple–areola complex undermining

Fibrosis after surgery creates tension on adjacent tissue, which results in NAC deviation towards the area of excision. Fortunately, NAC repositioning can be performed easily with simple undermining and this is a key component of both level I and II OPS. The first step is to completely transect the terminal ducts under the nipple and separate the NAC from the underlying breast tissue. A width of 0.5–1 cm of glandular tissue is generally left attached to the nipple to ensure the integrity of its vascular supply. This amount of subareolar tissue prevents NAC necrosis and limits venous congestion. Even if the nipple is undermined and the ducts divided immediately under the skin in most women (> 90%), the nipple will survive. The level of NAC sensitivity is reduced by extensive mobilisation and undermining and patients should be warned of this.7

Re-approximation of the glandular defect

During BCS, breast tissue is either re-approximated or left open allowing for the eventual formation of a haematoma or seroma. Seroma formation, however, does not always result in predictable long-term cosmetic results for larger volume excisions. Once reabsorption of the seroma occurs, the seroma absorbs and the excision cavity contracts due to fibrosis and retraction of the surrounding tissue, creating a noticeable defect together with distortion, which then results in NAC displacement. For this reason, where there has been an extensive resection, redistribution of the remaining breast volume to redistribute the loss is required. Tissue mobilised from lateral portions of the remaining gland or recruited from the central part of the breast allows the creation of glandular flaps that can be sutured together to close the defect (Fig. 6.6c).

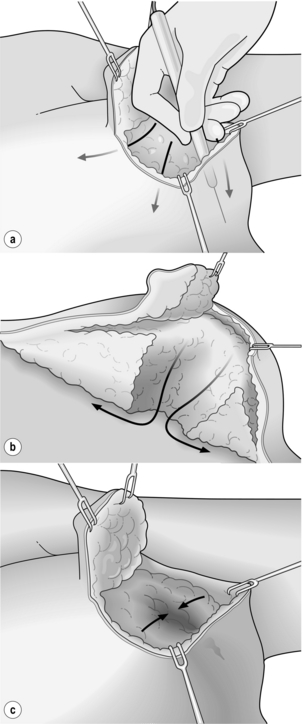

De-epithelialisation and NAC repositioning

Avoiding NAC displacement is a key element for both level I and II OPS. The NAC is repositioned to adjust for both the anticipated deviation of the nipple and the new shape of the breast. A crescentic area of periareolar skin opposite the excision defect is de-epithelialised (Fig. 6.7a–c). De-epithelialisation can be achieved using a scalpel blade or fine scissors. This technique is simple and safe and used systematically in aesthetic surgery of the breast. The vascular supply of the NAC after its separation from the gland and de-epithelialisation is based on the vasculature from the dermal plexus and this is not compromised by careful de-epithelialisation.8

Level II oncoplastic surgery

Atlas principles

The concept of the oncoplastic atlas is based primarily on tumour location. Initially used only for lower pole tumours, OPS has evolved to allow resection of breast lesions located almost anywhere in the breast. Different mammaplasty techniques have been adapted for specific locations in the breast.9

Level II OPS will generally result in a smaller breast that is rounder and higher on the chest wall than the contralateral breast, thus there is a need for a contralateral symmetrisation and the necessity to discuss this with the patient prior to the excision. Either immediate or delayed symmetrisation can be performed, depending on the amount of tissue resected and the desire of the patient. In a recent series of 175 women having an oncoplastic breast-conserving procedure, a contralateral breast reduction was performed in 25% of patients (19% during the initial operation and 6% as a secondary procedure). A higher rate of contralateral surgery was performed in patients who had an inverted-T mammaplasty (50% vs. 14% with other techniques; P < 0.001).10

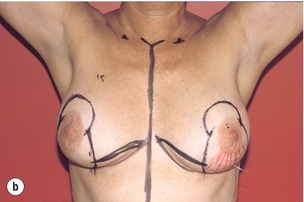

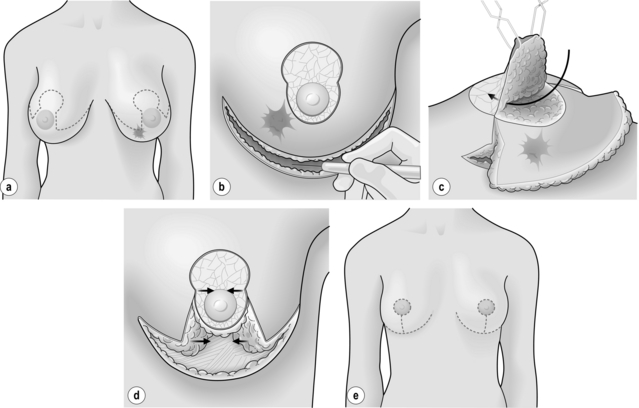

Lower pole location (4–7 o’clock)

The lower pole of the breast was the first location recognised to be at high risk of deformity following BCS.1 Removal of tissue from the 6 o’clock position results in retraction of the skin and downward deviation of the NAC, producing what is known as the ‘bird’s beak’ deformity, which results in a low level of patient satisfaction. A superior pedicle mammaplasty can permit large-volume excision of the lower pole without causing NAC deviation and has the added benefit of breast reshaping and elevation.

Techniques

‘Standard’ superior pedicle mammaplasty with inverted-T scar (Fig. 6.8a–e): The superior pedicle mammaplasty technique that is in routine use involves using the inverted-T and periareolar scars as utilised in most breast reductions.11 The procedure begins with the de-epithelialisation of the area surrounding the NAC. Once completed, the NAC is dissected away from the underlying breast tissue. A superior pedicle of dermoglandular tissue is preserved to provide the NAC with a blood supply.

Figure 6.8 Level II oncoplastic techniques for lower pole breast cancers: superior pedicle mammaplasty. (a) Treatment planning: superior pedicle mammaplasty and contralateral symmetrisation. (b) Superior pedicle de-epithelialised. Submammary fold incision. (c) Superior pedicle elevated. Wide excision of tumour and surrounding tissues. (d) Breast reshaping. (e) Result.

As for all BCS, the goal of the excision is to obtain at least a 1-cm macroscopic margin of normal tissue in order to ensure free microscopic margins. Mobilisation of the breast tissue from the pectoralis fascia allows for palpation of both the deep and superficial surfaces of the tumour, which improves the ability of the surgeon to obtain clear margins. The breast tissue is remodelled after the resection is completed. Remodelling incorporates the re-approximation of the medial and lateral glandular columns towards the midline to fill in the defect, followed by NAC recentralisation. All tissues excised should be weighed, as this provides a guide to the amount of tissue to be excised in any contralateral reduction procedure. As a general rule the resection of the cancer-bearing breast should be 10–20% less than excised from the opposite breast to allow for shrinkage of the treated breast following whole-breast radiotherapy. Results from excision of ductal carcinoma in situ at the lower pole of the left breast are shown in Fig. 6.9a and b. The result 2 years after operation is shown in Fig. 6.9c.

Vertical mammaplasty (Lejour/Lassus): One modification to the technique to excise lower quadrant tumours is to use the vertical-scar mammaplasty described by Lejour12 and Lassus.13 The site and volume of excision are identical to the inverted-T scar, but this approach avoids the submammary scar. In general, T-shaped reductions work best in the largest breasts and vertical scar reductions in smaller breasts.

Lower inner quadrant (7–9 o’clock)

Technique

V mammaplasty: This procedure involves excising a pyramidal section of skin and underlying breast tissue with the base located in the submammary fold and the apex at the border of the areola. This skin and underlying breast tissue are removed en bloc down to the pectoral fascia. An incision is then made along the inframammary fold and developed starting at the medial aspect of the base of resection moving towards the anterior axillary line and taken as far as necessary to perform adequate mobilisation of the breast tissue laterally. The lower pole of the breast is then mobilised off the pectoralis fascia medially and laterally for use as an advancement flap to fill the defect. Volume replacement is thus achieved through the advancement of the gland from the remaining lower medial and lateral aspects of the breast. The NAC is then recentralised on a de-epithelialised superior lateral pedicle.14

Upper inner quadrant (10–11 o’clock)

For moderate resections, level I techniques can be utilised safely and combined with immediate lipofilling to achieve a very smooth final contour. For more extensive excisions, the ability and likelihood of being able to preserve the natural breast shape should be discussed with the patient. Standard level II oncoplastic procedures that reliably address the specific limitations of BCS at this troublesome location are limited. Silverstein and colleagues have described an effective OPS procedure to address the upper inner quadrant. Their approach utilises a batwing excision pattern.15 Silverstein et al.’s OPS solution is innovative but excises tissue in excess of that which is required, leaves a large scar and, as described, removes pectoral fascia as well as skin. Immediate lipofilling may offer the best solution at present to this difficult area, combined with mobilisation and closure of the defect.

Upper pole (11–1 o’clock)

Lesions located at the 12 o’clock position can be excised widely followed by volume redistribution of tissue from a central location. Access to lesions in this location of the breast is accomplished either using an inferior pedicle or round-block mammaplasty approach. The inferior pedicle mammaplasty is commonly performed in the USA as a breast reduction technique and utilises an inverted-T scar pattern.16 A round-block approach, on the other hand, is more technically challenging when trying to achieve the desired breast shape. These two techniques are used extensively for breast reduction, with low complication rates and durable results. They can be applied for wide excision of upper pole tumours while preserving a patient’s natural breast shape. There are dangers with this technique when trying to preserve breast tissue superior to the nipple to advance into the defect. So-called ‘bottoming out’ is a problem with inferior mammaplasty techniques.

Techniques

Inferior pedicle mammaplasty: The skin markings are identical to those described for the superior pedicle reduction. The resection, however, is located in the upper pole, hence the vascular supply of the NAC is based on its inferior and posterior glandular attachments. The excision of the cancer is performed through an incision placed within the skin to be removed. Once the cancer has been excised and the specimen X-ray shows complete radiological excision, the inferior pedicle is de-epithelialised and advanced upwards towards the excision defect to achieve volume redistribution. Resection of the breast tissue is performed in the inner and outer lower quadrants to optimise the breast shape.

Round-block mammaplasty: The round-block mammaplasty utilises a periareolar incision and was originally described by Benelli.17,18 The procedure starts by making two concentric periareolar incisions, followed by de-epithelialisation of the intervening skin. The outer edge of de-epithelialised skin is incised and the entire skin envelope can then be undermined to allow access to the tumour. The NAC remains vascularised through its posterior glandular base. Resection of the lesion from the subcutaneous tissue down to the pectoralis fascia is performed and this results in the formation of an external and internal glandular flap. The flaps are then mobilised off the pectoralis fascia and advanced towards each other to eliminate the excision defect. The two incisions are then approximated, resulting in a periareolar scar.

Upper outer quadrant (1–3 o’clock; Fig. 6.10a–c)

In the upper outer quadrant, large lesions can usually be excised with standard BCS without causing deformity. However, resection of greater than 20% of the breast volume will result in retraction of the overlying skin with NAC displacement towards the excision site. A result of a patient with a T3 cancer treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and wide excision with mammaplasty is shown in Fig. 6.11a–d. Level II OPS can be utilised to increase resection possibilities while limiting deformity risk in this forgiving region of the breast.

Techniques

Fusiform mammaplasty: A large portion of the upper outer quadrant can be excised utilising a fusiform skin excision pattern oriented in a radial direction from the NAC towards the axilla, similar to a quadrantectomy.19,20 After wide excision, the reshaping is performed by mobilising the lateral and central gland into the cavity and suturing it together. Central gland advancement is accomplished easily following NAC undermining. Complete detachment of the retroareolar gland from the NAC enables the central part of the gland to be available for volume redistribution without compromise of NAC vascularity. Once the defect is eliminated, the NAC is placed in its optimal position, at the centre of the new breast mound. The area of glandular excision directly follows the skin excision. Additional glandular excision can be accomplished to remove almost the entire quadrant, depending on tumour size and the amount of tissue required to be removed to obtain clear margins.

Superior pedicled therapeutic mammaplasty: Given the increasing use of superomedial pedicles in breast reduction surgery, tissue that is normally removed from the lower breast can be kept alive on a superomedial pedicle and rotated into the upper outer quadrant. To be successful, care is needed to maintain a wide base to the pedicle and thus maintain a good blood supply to the whole of the tissue to be rotated.

Lower outer quadrant (4–5 o’clock)

A large-volume resection of the lower outer quadrant leaves a deformity similar to a bird’s beak. As for lower inner pole lesions, the inverted-T mammaplasty does not always ‘fit’ well for excisions within this quadrant. One option is a J-type mammaplasty described by Gasperoni et al.21

Techniques

J mammaplasty (Gasperoni): The first incision begins at the medial edge of the de-epithelialised periareolar area and then gently curves upwards with a concavity to the inframammary crease. The second incision starts at the lateral border of the de-epithelialised zone and follows a similar pattern. The parenchymal excision then follows the skin pattern in the shape of the letter J. The NAC remains vascularised on a de-epithelialised superior pedicle and is detached from the retroareolar gland. Lateral and central breast tissue can then be recruited into the excision defect to achieve an equitable redistribution of remaining breast volume.

Secondary pedicles: An alternative is to excise the cancer, leaving the skin intact through the incision selected for reducing the breast – be that a T-shaped or vertical scar. The skin that would normally be removed, is de-epithelialised and using primary pedicles attached to the nipple–areola complex or secondary pedicles attached to the inframammary fold, the defect is closed.

Retroareolar location

Subareolar breast cancers are candidates for BCS. However, superficial subareolar tumours are associated with a risk of NAC involvement approaching 50%.22 Such cases require en bloc removal of the NAC with the tumour. This results in a ‘flattened breast’ or ‘shark-bite’ deformity and poor cosmetic outcome unless techniques are used to avoid this. If the patient has a glandular breast that allows wide undermining for reshaping, a level I OPS is a reasonable option.

Level II mammaplasty techniques are reserved for patients with ptosis or fatty breasts or for patients for whom excision of more than 20% of the breast volume is required. There are a number of mammaplasty approaches that can be chosen for the centrally located lesion. They include the inverted-T mammaplasty with resection of the NAC, a modified Lejour or J pattern with NAC excision or a Grisotti flap (see Chapter 4). The latter offers the advantage of allowing for immediate NAC reconstruction through preservation of a skin island on an advancement flap.23

Technique

Modified inverted-T mammaplasty: Oncoplastic techniques for centrally located tumours have recently been outlined by Huemer et al.24 An inverted-T incision is preferred, similar to that used in a superior pedicle mammaplasty. The only modification is that the two vertical incisions encompass the NAC, which is removed together with the tumour. The breast shape is reconstructed as already demonstrated for the superior pedicle approach. The NAC is usually reconstructed at a later stage, after completion of radiotherapy, although it can be reconstructed during the same procedure. A modification of this technique is to leave a circular island of skin or an inferior dermoglandular flap, which is relocated in the position of the new NAC and produces symmetry with the opposite NAC (see Chapter 4).

Discussion

The integration of plastic surgery techniques at the time of tumour excision has delivered new alternatives, enabling surgeons to perform major resections involving more than 20% of breast volume without causing breast deformity. This new combination of oncological and reconstructive surgery is commonly referred to as oncoplastic surgery. This has allowed surgeons to extend the indications for BCS without compromising oncological goals or aesthetic outcomes. It is a logical extension of the quadrantectomy technique described by Veronesi et al.19 The innovation of the quadrantectomy provided women with a safe oncological option for conserving their breasts.

A major advantage of OPS is avoiding the need for secondary reconstruction by preventing major breast deformities.28 Prior to the development of OPS, patients with major deformities were referred subsequently to plastic surgeons.29 A classification system of these deformities has been described and reconstructive techniques for breast deformity after BCS have been developed30,31 (see Part 1 of this chapter). Despite continued efforts to treat these deformities, the results of postoperative repair of BCS defects in irradiated tissue are poor, regardless of the surgical procedure or team.32,33 Immediate reshaping of the breast will eliminate some of the need for these complex procedures.

Indications for oncoplastic surgery

The main indication for OPS is the need to excise large lesions or a significant percentage of the breast, so permitting BCS for large lesions for which a standard excision with safe margins would be either impossible or lead to major deformity. Extensive ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive lobular carcinoma, multifocality, and partial or poor responses to neoadjuvant therapy are areas where there may be benefits for OPS intervention. Standard BCS with positive margins where re-excision is being considered is an additional category of patients for whom OPS is appropriate.34

Oncoplastic and oncological safety

Large randomised prospective clinical trials have not validated the efficacy and safety of oncoplastic techniques, but there is growing evidence, through prospective series, that the techniques offer patients safe and effective surgical treatment. Our prospective analysis of over 100 patients undergoing OPS at our institution demonstrated 5-year overall and disease-free survival rates of 95.7% and 82.8%, respectively.11 Delay in adjuvant treatment was related to slow wound healing in only four patients, but all patients were able to receive appropriate postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy during the study. The cosmetic results at a median of 49 months in our most recent series of 175 pateints were favourable in 85% of patients.10 Final cosmetic outcomes and complication rates are not altered in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. A more recent retrospective review of 298 patients treated with OPS demonstrated a 5-year recurrence-free rate of 93.7% and 94.6% overall survival. This larger review confirms the equivalent outcomes of OPS and standard BCS.35 Rietjens et al. have reported long-term results from the European Institute of Oncology indicating no local relapse in the pT1 cohort. The pT2 and pT3 combined group had a 5-year local recurrence rate of 8% and a mortality rate of 15%. The overall local recurrence rate was determined to be 3%.36

Integration into multidisciplinary treatment

Clinical management is enhanced by OPS and does not change the need for or adherence to the guidelines for preoperative chemotherapy. Our surgical approach using OPS is fully integrated into the multidisciplinary environment. Radiation treatment is not disturbed by the extensive undermining during OPS and has complication rates comparable to BCS. There is no increase in treatment delays with the more extensive level II techniques, and the remodelling process does not affect continued screening and radiographic follow-up of patients.37

Complications of oncoplastic surgery

Mammaplasty techniques for cosmetic breast reduction have acceptable complication rates. Early common complications include seroma, haematoma, infection, and skin or NAC necrosis leading to delayed healing. Late complications during the postoperative course may involve fat necrosis, loss of nipple sensitivity and NAC necrosis.38,39

Extensive data are not available on complication rates for oncoplastic procedures. Our prospective evaluation of complications in an initial oncoplastic surgery series demonstrated low seroma rates (1%), but a higher overall incidence of delayed wound healing (9%). A delay in postoperative treatment was observed in only 4% of patients11 in our first series, falling to 1.7% in our most recent publication.10 This complication rate is not dissmimilar to that for cosmetic mammaplasty despite the need for greater glandular undermining in OPS compared to cosmetic breast reduction to achieve volume redistribution to less favourable tumour locations.

Limitations of oncoplastic surgery

Once an acceptable risk is established for the patient, then tumour characteristics are used to decide the appropriate procedure and the best approach. Excision of tumours too large to redistribute volume into the index quadrant may require a volume replacement procedure such as a latissimus dorsi miniflap.3 Location of the tumour is also critical, as upper inner quadrant tumours have few volume redistribution solutions, so immediate lipofilling in this location is the current best option.

References

1. Clough, K.B., Nos, C., Salmon, R.J., et al, Conservative treatment of breast cancers by mammaplasty and irradiation: a new approach to lower quadrant tumours. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(2):363–370. 7624409

2. Cothier-Savey, I., Otmezquine, Y., Calitchi, E., et al, Value of reduction mammaplasty in the conservative treatment of breast neoplasm. Apropos of 70 cases. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1996;41(4):346–353. 9183883

3. Rainsbury, R., Surgery insight: oncoplastic breast-conserving reconstruction – indications, benefits, choices and outcomes. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(11):657–664. 17965643

4. Bulstrode, N.W., Shortri, S., Prediction of cosmetic outcome following conservative breast surgery using breast volume measurements. Breast 2001; 10:124–126. 14965571

5. American College of Radiology. Breast imaging reporting and data systems (BI-RADS). Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2003.

6. Kraissl, C.J., The selection of appropriate lines for elective surgical incisions. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1951;8(1):1–28. 14864071

7. Schlenz, I., Rigel, S., Schemper, M., et al, Alteration of nipple and areola sensitivity by reduction mammaplasty: a prospective comparison of five techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(3):743–751. 15731673

8. O’Dey, D., Prescher, A., Pallua, N., Vascular reliability of the nipple–areola complex-bearing pedicles: an anatomical microdissection study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(4):1167–1177. 17496587

9. Smith, M.L., Evans, G.R., Gurlek, A., et al, Reduction mammaplasty: its role in breast conservation surgery for early-stage breast cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41(3):234–239. 9746077

10. Clough, K.B., Ihrai, T., Oden, S., et al, Oncoplastic surgery for breast cancer based on tumour location and a quadrant-per-quadrant atlas. Br J Surg. 2012;99(10):1389–1395. 22961518

11. Clough, K.B., Lewis, J., Couturaud, B., et al, Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg. 2003;237(1):26–34. 12496527

12. Lejour, M., Reduction of mammaplasty scars: from a short inframammary scar to a vertical scar. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1990;35(5):369–379. 1712564

13. Lassus, C., A 30-year experience with vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(2):373–380. 8559820

14. Clough, K.B., Kroll, S., Audretsch, W., An approach to the repair of partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(2):409–420. 10654684

15. Anderson, B.O., Masetti, R., Silverstein, M.J., Oncoplastic approaches to partial mastectomy: an overview of volume-displacement techniques. Lancet Oncol 2005; 6:145–157. 15737831

16. Spear, S.L., Pelletiere, C.V., Wolfe, A.J., et al, Experience with reduction mammaplasty combined with breast conservation therapy in the treatment of cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1102–1109. 12621180

17. Benelli, L., A new periareolar mammaplasty: the “round block” technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14(2):93–100. 2185619

18. Hammon, D.C., Short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction (SPAIR) mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(3):890–901. 10077079

19. Veronesi, U., Banfi, A., Saccozzi, R., et al, Conservative treatment of breast cancer. A trial in progress at the cancer institute of Milan. Cancer. 1977;39(6):2822–2826. 326380

20. Veronesi, U., Banfi, A., del Vecchio, M., et al, Comparision of Halsted mastectomy with quadrantectomy, axillary dissection, and radiotherapy in early breast cancer: long term results. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1986; 22:1085–1089. 3536526

21. Gasperoni, C., Salgarello, M., Gasperoni, P., A personal technique: mammaplasty with J scar. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;48(2):124–130. 11910216

22. Gerber, B., Krause, A., Reimer, T., et al, Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple–areolar complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):120–127. 12832974

23. Galimberti, V., Zurrida, S., Grisotti, A., et al, Central small size breast cancer: how to overcome the problem of nipple and areola involvement. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(8):1093–1096. 8518018

24. Huemer, G., Schrenk, P., Moser, F., et al, Oncoplastic techniques allow breast-conserving treatment in centrally located breast cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(2):390–398. 17632339

25. Veronesi, U., Luini, A., Galimberti, V., et al, Conservation approaches for the management of stage I/II carcinoma of the breast: Milan cancer institute trials. World J Surg. 1994;18(1):70–75. 8197779

26. Mariani, L., Salvadori, B., Veronesi, U., et al, Ten year results of a randomized trial comparing two conservative strategies for small size breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(8):1156–1162. 9849473

27. Amichetti, M., Busana, L., Caffo, O., Long term cosmetic outcome and toxicity in patients treated with quadrantectomy and radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncology 1995; 52:177–181. 7715900

28. Dewar, J.A., Benhamou, E., Arrigada, R., et al, Cosmetic results following lumpectomy, axillary dissection and radiotherapy for small breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1988;12(4):273–280. 3187067

29. Petit, J-Y., Regault, L., Zekri, A., et al, Poor aesthetic results after conservative treatment of breast cancer. Techniques of partial breast reconstruction. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 1989; 34:103–108. 2472100

30. Clough, K.B., Cuminet, J.C., Fitoussi, A., et al, Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: classification and results of surgical correction. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41(8):471–481. 9827948

31. Clough, K.B., Thomas, S., Fitoussi, A., et al, Reconstruction after conservative treatment for breast cancer. Cosmetic sequelae: classification revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(7):1743–1753. 15577344

32. Berrino, P., Campora, E., Leone, S., et al, Correction of type II breast deformities following conservative cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 90:846–853. 1410038

33. Bostwick, J., Paletta, C., Hartampf, C.R., Conservative treatment for breast cancer: complications requiring reconstructive surgery. Ann Surg 1986; 203:481–490. 3010888

34. Schwartz, G.F., Veronesi, U., Clough, K.B., et al, Proceedings of the consensus conference on breast conservation, April 28 to May 1, 2005, Milan, Italy. Cancer. 2006;107(2):242–250. 16770785

35. Staub, G., Fitoussi, A., Falcou, M.C., et al, Breast cancer surgery: use of mammaplasty. Results from a series of 298 cases. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007;53(2):124–134. 17949880

36. Rietjens, M., Urban, C.A., Petit, J.Y., et al, Long-term oncologic results of breast conservation treatment with oncoplastic surgery. Breast. 2007;16(4):387–395. 17376687

37. Brown, F.E., Sargernt, S.K., Cohen, S.R., et al, Mammographic changes following reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80(5):691–698. 3671561

38. Spear, S.L., Evans, K.K. Complications and secondary corrections after breast reduction and mastopexy. Surg Breast. 2006; 2:1220–1234.

39. Munhoz, A.M., Montag, E., Arruda, E.G., et al, Critical analysis of reduction mammaplasty techniques in combination with conservative breast surgery for early breast cancer treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(4):1091–1103. 16582770