23 Oncologic emergencies

Metastatic spinal cord compression

Aetiology

The mechanisms by which MSCC may develop include:

Spinal cord metastases can be of three types depending on the location of tumour deposit:

Clinical features

Autonomic dysfunction is a late complication affecting up to 50% of patients with MSCC. It includes impotence, bladder and bowel dysfunction, with constipation occurring most frequently.

There are two clinical variants of MSCC, which require early recognition:

Investigations

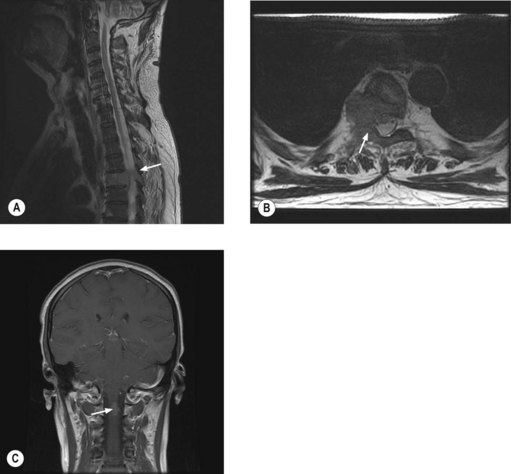

MRI of the whole spine is the investigation of choice for suspected MSCC. CT is used only when MRI is contraindicated. A sagittal screening of the whole spine with T1 and short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) images should be done to ensure that multiple levels of compression are not missed and also to identify asymptomatic metastases. T2 weighted images help to detect the degree of compression by a soft tissue component and intramedullary lesions (Figure 23.1).

Management

The aim of treatment is to preserve or improve neurological function and achieve pain control. 70–100% patients who are ambulant at the beginning of treatment remain ambulant with prompt treatment, whereas only 30–50% patients who are non-ambulant regain the ability to walk and only 5–10% of paraplegic patients become ambulant. Hence it is important to have definitive treatment within 24 hours of presentation with suspected cord compression. Patients with MSCC secondary to a vascular event will not respond to treatment.

Specific measures

Surgery may involve decompression, stabilization and or resection and reconstruction of the spinal canal. The patient’s overall prognosis and performance status should be taken into consideration and patients who have had no distal neurological function for >24 h should not be considered for surgery (Boxes 23.1 and 23.2).

Box 23.1

Patients with MSCC according to outcome after surgical intervention

| Good surgical candidates | Poor surgical candidates |

|---|---|

| ‘Good prognosis tumours’ e.g. breast cancer, testicular cancer etc. | ‘Poor prognosis tumours’ e.g. lung cancer, melanoma |

| Single level of compression with solitary or few vertebral metastases | Multiple levels affected or multiple spinal metastases |

| Absence of visceral metastases | Presence of visceral metastases |

| Good neurological function | Poor neurological function |

| No previous radiotherapy | Recurrence following radiotherapy |

| Minimal co-morbidity | Medically unfit for surgery |

| Unknown primary or no histopathological diagnosis | Prognosis <3 months |

Radiotherapy is the treatment most frequently used and is most effective for patients with radiosensitive tumours who are ambulatory at the beginning of treatment. For those without mechanical pain or structural instability, radiotherapy may significantly improve pain control and neurological function. The most commonly used regimes are 20 Gy in five fractions (more appropriate for patients with expected short survival) or 30 Gy in 10 fractions (Box 23.3). Some patients may deteriorate during radiotherapy when the steroid dose may be increased or they may be considered for surgery if appropriate. Patients with established paraplegia are treated with an 8 Gy single fraction for pain control.

Box 23.3

Radiotherapy in spinal cord compression

The issue of whether surgery or radiotherapy or a combination of both gives best functional outcome is yet to be resolved. A randomized study compared radiotherapy (30 Gy in 10 fractions) started within 24 hours of onset of MSCC with surgery within 24 hours followed by radiotherapy within 2 weeks of surgery. Results showed that initial surgery followed by radiotherapy offers a longer period with ability to walk compared with those treated with radiotherapy alone (median, 126 days vs. 35 days, p = 0.006). This study showed that surgery permits most patients to remain ambulatory and continent for the remainder of their lives, while patients treated with radiation alone spend approximately two-thirds of their remaining time unable to walk and incontinent. However, results of this study may not be extended to all patients as the study was limited to patients with less radiosensitive tumours and with different tumour types and presentations.

Prognosis

The median survival following a diagnosis of MSCC is 3–6 months, with 17% of patients alive at 1 year and 10% alive at 18 months. Pre-treatment motor function is an important predictor of the ambulatory outcome. Patients who develop motor dysfunction more slowly also may have a better outcome.

Paediatric spinal cord compression

Paediatric MSCC differs from adult MSCC in that it is often caused by chemosensitive histological types not seen in adults such as neuroblastoma, Wilms’ tumour (p. 323). The usual pathogenesis is the direct invasion of tumour through neural foramina. The most common histologic type is neuroblastoma, which responds to chemotherapy. Decompressive surgery is offered when patients present with rapid progression or progress during chemotherapy. Radiotherapy is only offered when there is no response after chemotherapy and/or surgery and for those who require palliation after failure of multiple systemic regimens.

Raised intracranial pressure

Approximately 25% of patients with cancer develop brain metastases and can present with features of raised intracranial pressure and focal neurological deficits. Seizures and bleeding into the metastases can result in an acute medical emergency. Malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, thyroid cancer and choriocarcinoma are commonly associated with bleeding into the metastases. Initial treatment is dexamethasone 16 mg daily. Patients who present with seizures require anticonvulsants. Role of prophylactic anticonvulsants is not known; it may be considered in patients with high risk features of seizure such as metastasis to the motor cortex, bleeding metastasis and leptomeningeal metastasis. Further management of brain metastasis is given on p. 278.

Encephalopathy

Clinical features

Management

In patients with ifosfamide encephalopathy, treatment is based on the grade of the encephalopathy:

Febrile neutropenia

Introduction

Febrile neutropenia is one of the most common complications of cancer treatment. 50–60% of patients with febrile neutropenia have an established or occult infection and 20% of patients with a neutrophil count ≤1.0 × 109/l have bacteraemia.

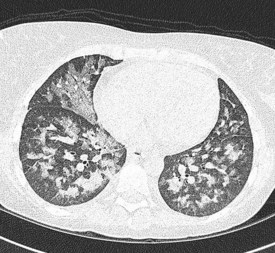

In the majority of cases, bacterial pathogens are responsible for febrile neutropenic episodes with fungal (Figure 23.3), viral and protozoal infections occurring more commonly as secondary events. Currently, Gram-positive bacteria account for 60–70% of microbiologically detected infections, which may in part be due to the prevalent use of quinolones as prophylactic antibiotics. Other possible causes of this change in trend include widespread use of intravenous catheters, along with more profound and prolonged neutropenia due to intensive and recurrent treatment regimes.

Clinical presentation and assessment

It is important to enquire and look for signs of infection at the following sites:

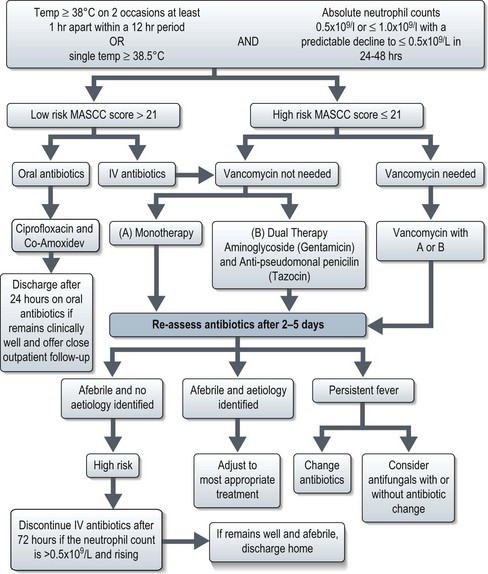

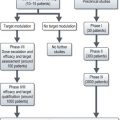

Management (Figure 23.4)

The mainstay of management is the prompt administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) scoring system categorizes patients with febrile neutropenia into low and high-risk groups (Box 23.4). Patients with low-risk febrile neutropenia can be managed with oral antibiotics and discharged after 24 hours observation, whereas those with high risk febrile neutropenia require intravenous antibiotics (Figure 23.4).

Low risk – a score of >21.

High risk – score of ≤21.

b Does not apply to patients <16 yrs. Initial monocyte count >1.0 × 109/l, no co-morbidity and normal chest radiograph findings indicate children at low risk for significant bacterial infections.

The most commonly used antibiotic regime for high-risk febrile neutropenia is a combination of broad-spectrum, anti-pseudomonal penicillin (e.g. Tazocin) with an aminoglycoside (e.g. Gentamicin). The synergistic effect of combination therapy can be beneficial and dual treatment reduces the risk of drug resistant strains emerging. Alternatively, a carbopenem (e.g. meropenem) can be used as monotherapy in uncomplicated episodes of neutropenic fever when it has been shown to be equally as effective as dual therapy. Vancomycin may be added to mono- or dual-therapy when the patient is felt to be at high risk of Gram-positive bacteraemia (Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in those with central venous access and severe sepsis with or without hypotension). Gram-positive coverage should also be considered in patients with suspected skin infection or severe mucosal damage and when prophylactic antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria have been used.

Haematopoietic colony stimulating factors

CSF use is recommended in both the therapeutic and the prophylactic setting for patients at high risk of developing infection-associated complications or who have prognostic factors predictive of a poor clinical outcome (Box 23.5).

Thrombocytopenia

Patients without bleeding, and a platelet count of >10 × 109/l (>20 × 109/l if with ongoing infection) may be managed conservatively. Patients with a platelet count of <10 × 109/l (<20 × 109/l in those with infection) or those with bleeding need random donor platelets. The aim of a platelet transfusion is to maintain platelets above 10 × 109/l (20 × 109/l in those with infection) in the prophylactic setting, to stop bleeding in those with bleeding, and to maintain platelets above 50 × 109/l in those with life-threatening bleeding. Each five donor unit or one single donor apheresis pack increases the platelet count by approximately 10 × 109/l at 24-hours post-transfusion. In the absence of such an increment, platelet refractoriness should be suspected and managed appropriately.

Superior vena cava obstruction

Investigations

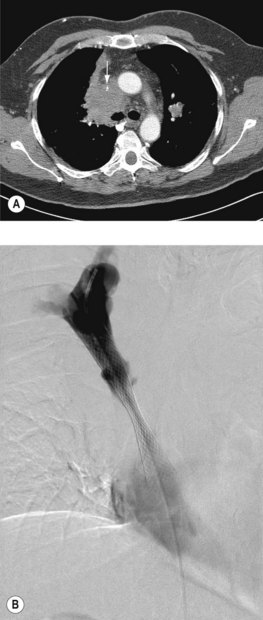

A plain chest radiograph will often show a right paratracheal mass or widened mediastinum. A CT scan will demonstrate SVC compromise and distinguishes between external compression and thrombus (Figure 23.5). In patients without a histologic diagnosis, a biopsy is required prior to deciding treatment.

Management

General measures include oxygen, dexamethasone 16 mg daily, and diuretics. Endovascular stent insertion (Figure 23.5) is the gold-standard treatment which relieves obstruction in 95% of cases, usually within 72 h (Box 23.6). Complications of stent placement are in the region of 3–7% and include: transient chest pain, infection, misplaced stent, stent migration and pulmonary emboli. SVCO recurs in approximately 11% of patients (due to stent occlusion secondary to either thrombus or tumour in-growth). However, secondary patency rates are good and long-term patency is achieved in 92% of patients.

Box 23.6

Indications for endovascular stent insertion

Radiotherapy was traditionally used first line for the treatment of SVCO prior to endovascular stenting. In radiosensitive tumours, radiotherapy results in symptomatic response rates of up to 78% at 2 weeks. However, complete resolution of obstruction is seen in only 31% on serial venograms with a partial resolution in 23%.

Radiotherapy is given to a dose of 20 Gy in five fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions.

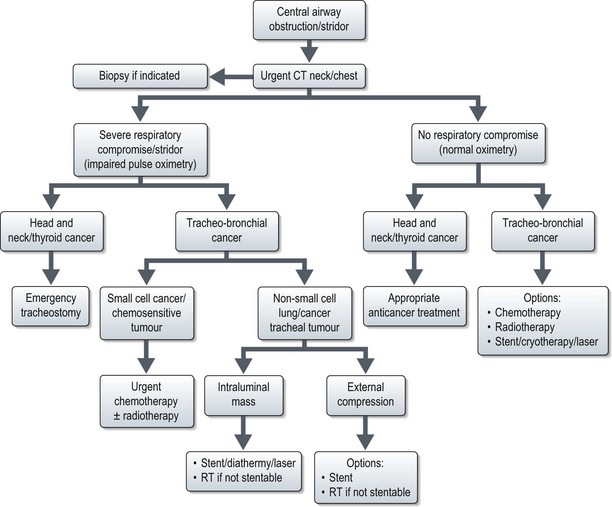

Central airway obstruction and stridor

Malignant central airway obstruction produces progressive symptoms of dyspnoea, stridor and obstructive pneumonia. A central airway narrowing to <25% cross sectional area is usually needed to produce dyspnoea and stridor at rest. Airway obstruction can be produced by either extrinsic or intrinsic compression.

Further management is shown in Figure 23.6. Stent results in prompt relief of symptoms; with cryotherapy 75% achieve symptomatic relief. Radiotherapy is given either as 20 Gy in five fractions or 30 Gy in 10 fractions. Radiotherapy response usually occurs within 72 hours with 70–95% patients becoming symptom-free by 2 weeks.

Malignancy associated hypercalcaemia

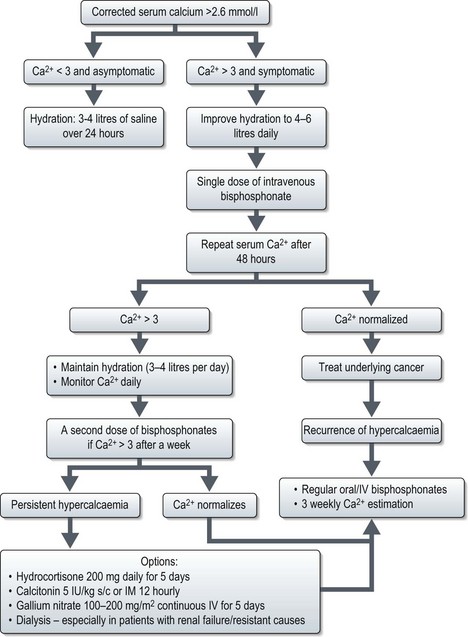

Management (Figure 23.7)

Saline rehydration is an important aspect of the management of hypercalcaemia. Hydration alone may adequately treat mild hypercalcaemia. Hypercalcaemic patients are universally dehydrated as a result of calcium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and poor oral intake. The speed of administration of normal saline depends on the degree of dehydration and renal impairment, the level of hypercalcaemia and the patient’s underlying cardiac function. Fluid balance must be carefully monitored. The aim of saline treatment is two-fold, firstly, to increase the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and thereby increase the filtered load of calcium into the tubular lumen from the glomerulus. Secondly, calcium reabsorption is inhibited in the proximal nephron because of the calciuretic effects of saline. Once dehydration has been adequately treated, loop diuretics can be used to increase calcium excretion. Any drug that may be contributing to the hypercalcaemia e.g. thiazide diuretics, lithium and calcium supplements should be discontinued. Hypophosphataemia is common and phosphate levels should hence be monitored and replaced as appropriate.

Acute tumour lysis syndrome

Introduction

ATLS is most frequent in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (especially Burkitt’s lymphoma), acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). It has also been rarely reported following the treatment of ovarian, breast and small-cell lung cancer. Several characteristics inherent to the tumour type predispose to TLS and these include high tumour proliferation rate, large tumour burden, tumour chemosensitivity and increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Pre-existing uraemia or hyperuricaemia, decreased urinary flow, low urinary pH, dehydration, oliguria and renal impairment have also been identified as risk factors for TLS.

Clinical features

ATLS is characterized by hyperuricaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hypocalcaemia and hyperkalaemia. These biochemical abnormalities lead to a range of non-specific symptoms (Table 23.1). When the electrolytes are severely deranged, patients are at risk of seizures, cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death.

Table 23.1 Biochemical and clinical features of tumour lysis syndrome

| Biochemical abnormality | Clinical consequence |

|---|---|

Management

Specific management of established ATLS includes the close monitoring of uric acid, phosphate, potassium, creatinine, calcium and LDH levels. Fluid balance should be measured and electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected (Table 23.2). Haemodialysis and intensive care facilities should be available if required.

| Electrolyte abnormality | Management |

|---|---|

| Hyperphosphataemia |

Hypersensitivity reactions

Introduction

Nearly all systemic agents used to treat cancer have the potential to cause hypersensitivity reactions; however, severe reactions are rare. Provided patients receive appropriate pre-medication, close monitoring and prompt intervention when required, severe hypersensitivity reactions occur in less than 5% of patients. Platinum compounds, taxanes and monoclonal antibodies are most likely to cause a reaction, although the timing of such reactions may differ, as do their likely underlying aetiology (Table 23.3).

Table 23.3 Showing the incidence of any grade hypersensitivity in a range of chemotherapy agents

| Drug | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Carboplatin or oxaliplatin | 12–19% |

| Paclitaxel | 8–45% |

| Docetaxel | 5–20% |

| Trastuzumab | 40% |

| Rituximab | Up to 77% |

| Cetuximab | 16–19% |

Platinum compounds such as cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin classically cause reactions following multiple cycles of treatment, typically after 6–8 doses. This is consistent with a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction following repeated exposure to the drug and leads to IgE-mediated release of histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins from mast cells in the tissues and basophils in the peripheral blood. This causes smooth muscle contraction and peripheral vasodilatation, leading to urticaria, rash, angioedema, bronchospasm and hypotension.

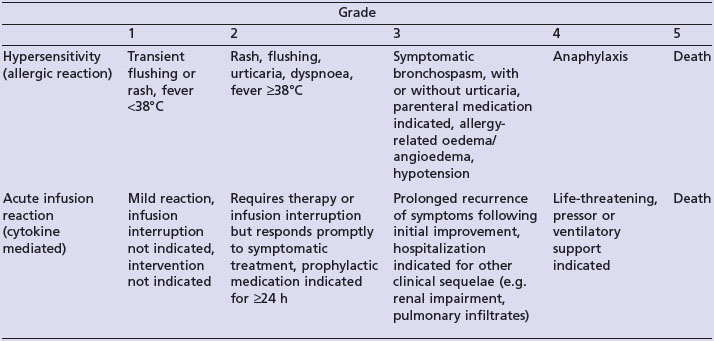

Clinical features

The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) distinguish between hypersensitivity and acute infusion reactions (Table 23.4).

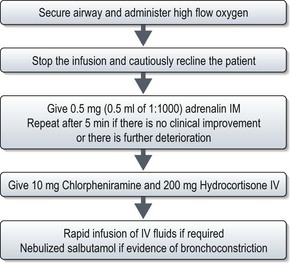

Management

Treatment of anaphylaxis is outlined in Figure 23.8.

Re-challenging patients following a hypersensitivity reaction depends on the aim of treatment and the severity of the reaction. The majority of patients who have a mild–moderate reaction during their first drug exposure (often seen with taxanes and monoclonal antibodies) are likely to tolerate re-challenge of the drug if pre-medication is used with a slower rate of infusion. Desensitization protocols have been used with some success in patients who have a reaction to taxanes, however, re-challenge of platinum compounds is usually less successful with approximately 50% of patients experiencing recurrent hypersensitivity reactions.

Extravasation

Introduction

Vesicant drugs are more likely to lead to extravasation because of their potential for endothelial damage (Table 23.5). The risk of vesicant extravasation is very low, in the range of 0.01–6% and although the use of implanted ports reduces the risk of extravasation, it can still occur.

| Vesicant drugs | Non-vesicant/irritant/exfoliant drugs |

|---|---|

| Busulfan | Bevacizumab |

| Carmustine | Bleomycin |

| Dactinomycin (Actinomycin D) | Carboplatin |

| Daunorubicin | Cisplatin |

| Doxorubicin | Cyclophosphamide |

| Epirubicin | Cytarabine |

| Mitomycin C | Cetuximab |

| Treosulfan | Docetaxel |

| Vinblastine | Etoposide |

| Vincristine | Fludarabine |

| Vinorelbine | Fluorouracil |

| Gemcitabine | |

| Ifosfamide | |

| Irinotecan | |

| Liposomal doxorubicin | |

| Methotrexate | |

| Oxaliplatin | |

| Paclitaxel | |

| Rituximab | |

| Topotecan | |

| Trastuzumab |

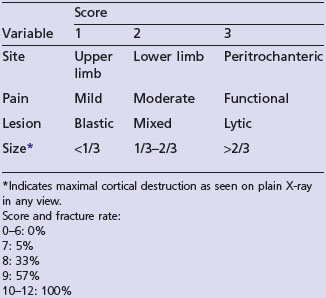

Bone fractures or impending fractures

Bone metastasis is the third most common site of metastatic disease. Bone metastasis can be lytic, sclerotic and mixed. Risk of pathological fracture is highest in lytic lesions. 50% of pathological fractures are due to metastatic breast cancer and the commonest site is femur. A lesion involving 50% of the cortex, 2.5 cm in diameter, or which remains painful after weight-bearing after radiotherapy is at risk of a pathological fracture (Figure 23.9).

Plain X-ray will reveal bone metastases in long bones, and it is helpful in deciding Mirel’s scoring (Table 23.6).

Other emergencies

Chemotherapy induced haemorrhagic cystitis

Scott-Brown M, Spence R, Johnston P. Emergencies in Oncology. Oxford University press; 2007.

Samphao S, Eremin JM, Eremin O. Oncological emergencies: clinical importance and principles of management. Eur J Cancer Care. 2009 Dec 17. [Epub]PMID: 20030695

Walji N, Chan AK, Peake DR. Common acute oncological emergencies: diagnosis, investigation and management. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:418-427.

Marti FM, Cullen MH, Roila F, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of febrile neutropenia: ESMO clinical recommendations. Ann Oncol.. 2009;20(Suppl 4):166-169.

Innes H, Marshall E. Outpatient therapy for febrile neutropenia. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:294-298.