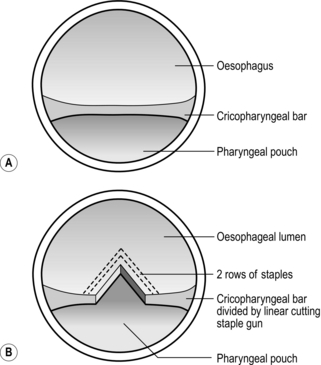

Oesophagus

ENDOSCOPY

Appraise

1. Endoscope every patient with dysphagia except when this is fully explained by the presence of neurological or neuromuscular disease.

2. Endoscope patients with suspected disease in the oesophagus producing pain on swallowing (odynophagia), heartburn not responding to simple medication or arising de novo in patients over 50 years, bleeding, or if accidental and iatrogenic damage are suspected.

Prepare

1. Ensure that the endoscope, the ancillary equipment and necessary spares are available, function correctly and are appropriately sterile. The endoscope must be thoroughly prepared between procedures according to the maker’s instructions. Fibreoptic instruments, biopsy forceps and similar instruments are scrupulously cleaned using neutral detergent and usually disinfected with 2% alkaline glutaraldehyde. This is capable of eliminating all infective organisms, including HIV. Washing and sterilization are performed mechanically in an automatic machine to avoid exposure of endoscopy room staff to glutaraldehyde fumes.

2. Modern gastrointestinal endoscopes are slim, versatile, have remarkably flexible tips and can be passed with pharyngeal anaesthesia alone in most patients. They are safe, relatively comfortable for the patient and allow examination of the stomach and duodenum beyond. Use the end-viewing instrument routinely since it gives the best general view. Through it can be passed biopsy forceps, cytology brushes, snares, guidewires for dilators and needles for injection. Argon plasma coagulation or Nd-YAG laser may be applied through it for the palliation of inoperable neoplasms or for the treatment of Barrett’s oesophagus. The technology of endoscopes is steadily improving and the rigid oesophagoscope is, to all intents and purposes, obsolete.

3. Obtain signed informed consent from the patient.

4. Remove dentures from the patient.

5. Except in an emergency, have the patient starved of food and fluids for at least 5 hours. In an emergency, especially in patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage who cannot wait 5 hours for the stomach to empty, a crash general anaesthetic with cricoid pressure is the safest means of securing the airway and preventing aspiration.

6. Obtain a preliminary barium swallow X-ray if there is a suspected pharyngeal pouch.

7. Attach a pulse oximeter probe to the patient’s finger if sedation is being used, and ensure that there are sufficient numbers of staff in the endoscopy room for safe care of a sedated patient.

8. Spray the pharynx with lidocaine solution just before passing the endoscope.

9. In anxious patients, or those in whom intervention (e.g. dilatation) is required, insert a small plastic cannula into a peripheral vein and through it inject slowly 1–2 mg of midazolam until the patient’s eyelids just begin to droop. Remember that it takes 2 minutes for the full effect of midazolam to develop.

FIBREOPTIC ENDOSCOPY

1. Lay the patient on the left side with hips and knees flexed. Place a plastic hollow gag between the teeth. Ensure that the patient’s head is in the midline and that the chin is lowered on to the chest.

2. Lubricate the previously checked end-viewing instrument with water-soluble jelly.

3. Pass the endoscope tip through the plastic gag, over the tongue to the posterior pharyngeal wall. Depress the tip control slightly so that the instrument tip passes down towards the cricopharyngeal sphincter. Do not overflex the tip or it will be directed anteriorly and enter the larynx. Visualize the larynx and pass the endoscope just behind it.

4. Ask the patient to swallow. Do not resist the slight extrusion of the endoscope as the larynx rises, but maintain gentle pressure so that it will advance as the larynx descends and the cricopharyngeal sphincter relaxes. Advance the endoscope under vision, insufflating air gently to open up the passage. Aspirate any fluid. Spray water across the lens if it becomes obscured. If no holdup is encountered, pass the tip through the stomach into the duodenum then withdraw it slowly, noting the features. Remove biopsy specimens and take cytology brushings from any ulcers, tumours or other lesions.

5. If a stricture is encountered note its distance from the incisor teeth. Sometimes the instrument will pass through, allowing the length of the stricture to be determined. Always remove biopsy specimens and cytology brushings from within the stricture. If the stricture is benign in appearance, gentle dilatation to 12 mm can be attempted if the patient is symptomatic. Dilatation of malignant strictures is not indicated as any benefit is short-lasting and the risk of perforation is high (6–8%). Get biopsies and confirm the diagnosis prior to intervention. If nutritional support is required, fluoroscopic passage of a feeding nasogastric tube can be performed.

Assess

1. Note the level of each feature. The cricopharyngeal sphincter is approximately 16 cm from the incisor teeth. The deviation around the aortic arch is 28–30 cm, the cardia lies at 40 cm and here the lining changes abruptly from the pale, bluish, stratified oesophageal epithelium to the florid, pinker, gastric columnar-cell epithelium.

2. Oesophagitis is usually from gastro-oesophageal reflux, but is not necessarily associated with hiatal hernia. Consult a colour chart that illustrates the grades of oesophagitis. Most commonly there are red streaking erosions just above the cardia. Oesophagitis may be seen above a benign stricture. Occasionally, in advanced achalasia, one may see a mild diffuse oesophagitis from contact with fermenting food residues. Thick white plaques indicate monilial infection, usually in association with oral involvement. Confirm the diagnosis by taking mucosal scrapings.

3. Sliding hiatal hernia produces a loculus of stomach above the constriction of the crura with a raised gastro-oesophageal mucosal junction. To determine the level of the hiatus, ask the patient to sniff, and note the level at which the crura momentarily narrow the lumen. Reflux and oesophagitis may be visible. A rolling hernia is visible only from within the stomach by inverting the tip of a flexible instrument to view the apparent fundic diverticulum. If the diagnosis is a possibility, confirm with a barium study.

4. Frank ulceration in the oesophagus is unusual, but may be due to severe reflux disease. In Barrett’s oesophagus the lower gullet is lined with modified gastric mucosa and an ulcer may develop in the columnar-lined segment. In all cases of Barrett’s take biopsies of the columnar segment from all four quadrants at 2-cm intervals. In patients with dysplasia even more biopsies are required for accurate assessment. Use ‘jumbo’ forceps. Ulcerating carcinomas may develop at any level. In most Western countries the majority of cancers comprise adenocarcinomas and these arise in the lower oesophagus in association with Barrett’s oesophagus. Take multiple biopsies and cytological brushings from a number of areas of all ulcers.

5. Strictures from peptic oesophagitis or, rarely, ulceration in a Barrett’s oesophagus develop at any time from birth onwards, but more frequently occur in middle or old age. Almost always there is a coincidental hiatal hernia. If there is no hernia below the stricture, suspect cancer. Also suspect cancer if there is food residue above a stricture. Food residue may also be seen in achalasia and may be the only diagnostic clue. Take multiple biopsies and brushings for cytology. The cause of Schatzki’s ring is unknown. It is usually asymptomatic, seen radiologically at the junction between gastric and oesophageal mucosa. Caustic strictures develop at the sites of hold-up of swallowed liquids at the cricopharyngeus, at the aortic arch crossing and at the cardia. Webs or strictures in the upper oesophagus are uncommon. However, it is not unusual to see a patch or ring of ectopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus 1–2 cm below the cricopharyngeus, the so-called ‘inlet patch’. Stricture may arise from external pressure, of which by far the most common cause is bronchogenic carcinoma.

6. Mega-oesophagus may be seen in achalasia of the cardia, but is now uncommon as most cases are diagnosed long before dilatation takes place. Mega-oesophagus may also be seen in the South American Chagas’ disease and in some cases of advanced scleroderma.

7. Pulsion diverticula are related to abnormal oesophageal motility and are seen above the cricopharyngeus muscle (Zenker’s diverticulum or pharyngeal pouch) and above segments of presumed spasm. Traction diverticula in the mid-oesophagus develop as a result of chronic inflammation of mediastinal glands, especially from tuberculosis.

8. Oesophageal varices are usually recognized just above the cardia as convoluted varicose veins, which may extend into the upper stomach.

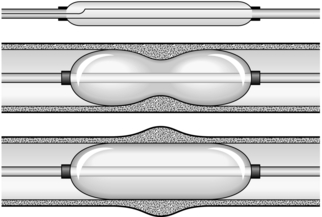

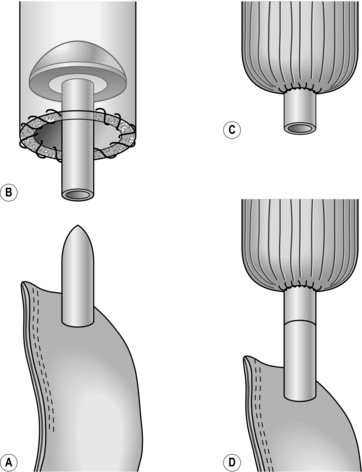

DILATATION OF STRICTURES (Fig. 8.1)

1. Fragile strictures do not always require endoscopic dilatation if the diagnosis is not in doubt or has been confirmed by endoscopy. The safest oesophageal dilator is soft, solid food, provided that each bolus contains only aggregated small particles.

2. Record the distance of the stricture from the incisor teeth. If the stricture is short and appears benign, the best means for dilatation is by a through-the-channel balloon. These balloons have a fixed maximum diameter of 2 cm (60 F). Always check for perforation with endoscopy after dilatation. An alternative to these balloon dilatators are soft mercury-laden Maloney dilators. If problems occur inserting them through a tortuous stricture, balloon dilatation using a hydrophilic guidewire inserted under fluoroscopic control should be undertaken.

3. First outline the passage by getting the erect patient to swallow a thin contrast medium. Now introduce a fine, flexible guidewire through a nostril into the oesophagus and negotiate the tip through the stricture using a combination of rotating it and getting the patient to swallow a little water or more contrast medium to outline the passage. Now pass a well-lubricated catheter fitted with a deflated balloon over the guidewire and insinuate it through the stricture. The proximal and distal ends of the balloon have radio-opaque markers so that it can be placed accurately. Carefully inflate the balloon, watching it on the screen. A waist appears at the level of the stricture and as the pressure is gradually increased this disappears. If the patient is apprehensive or complains of discomfort, temporarily stop inflating the balloon.

4. Most strictures can be dilated at a single session, but do not persist unduly in the face of difficulty or discomfort. When the balloon is withdrawn, check to see if there is any blood on it. Now give the patient some contrast medium to swallow and carefully watch it pass through the stricture to ensure that there is no leak.

REMOVAL OF FOREIGN BODIES

Appraise

1. Swallowed articles impact at the sites of narrowing. Objects at the cricopharyngeus muscle are regurgitated but those that pass this point may impact at the crossing of the aortic arch or at the cardia. However, the normal oesophagus is extremely distensible and smooth objects usually pass into the stomach. The most frequent causes of impaction are pre-existing stricture or a sharp foreign body that penetrates the oesophageal wall.

2. Remember that many impacted foreign bodies are radiolucent. Sometimes they are demonstrable on X-rays by giving the patient a drink of water-soluble contrast medium.

3. Most foreign bodies may be removed using a variety of methods in conjunction with fibreoptic endoscopes and an overtube under local anaesthesia with sedation. If a foreign body cannot be removed with modern endoscopic instruments an operation is probably required. Deeply and firmly impacted foreign bodies may require thoracotomy and oesophagotomy to remove them.

4. A smooth foreign body, or a food bolus, may be gently pushed into the stomach. As a rule it will pass through the gut but if it remains in the stomach removal is easier than from the oesophagus.

Action

1. There is a classic repertoire of methods to remove foreign bodies through the rigid oesophagoscope. The grasping forceps are strong and versatile, and can cope with open safety pins and coins. Version and extraction of an open safety pin with the point facing upwards is now part of the folklore of oesophageal surgery. However, the use of the rigid endoscope is not now to be encouraged. There are safer and better methods.

2. Ingenious methods have been used to remove foreign bodies using the end-viewing fibreoptic endoscope. The foreign body may be grasped with forceps or caught with a snare and withdrawn together with the instrument. An external flexible sheath may be pushed over the end of the endoscope tip into which a sharp foreign body can be drawn to protect the mucosa from injury. A variety of snares and grasping forceps should be kept available.

INJECTION OR BANDING OF VARICES

Appraise (see Chapter 17)

1. Recognize these as soft, collapsible, projecting columns in the lower oesophagus, sometimes continuing into the gastric cardia.

2. In patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding who are found to have varices, do not assume that the bleeding is from the varices. A high proportion of such patients have another cause such as peptic ulcer, so always carry out a complete examination.

3. The varices thrombose when injected with ethanolamine oleate warmed to reduce its viscosity. An injection needle is passed down the biopsy channel and 2–5 ml is injected into each varix. The injections are repeated at intervals of 3–4 weeks until the varices are obliterated.

4. Banding of varices has a number of advantages, including better immediate control of active bleeding. A banding device that can fire several bands is loaded into and onto the endoscope. Always read the instructions on the device. Continuous design improvement is the norm and the device may have changed since you last used it. The varix is identified and then sucked into the banding cap on the end of the endoscope. When a ‘red-out’ is achieved the bander is fired and the suction released. The band should be seen clearly in the required position. Multiple varices can be ligated at a single session.

INTUBATION OF TUMOURS

Appraise

1. It is not necessary to intubate all strictures that cannot be resected. Malignant strictures that will be submitted to chemo-or radiotherapy may deteriorate temporarily and later expand, so it is worthwhile deferring intubation. Intubation of benign strictures is not recommended unless in exceptional cases in very frail subjects with a limited life-expectancy. Intubation produces a rigid channel through which food must fall by gravity and which can easily become blocked, so reserve its use for patients with real need.

2. The development of expanding metal stents is a considerable advance and has replaced the rigid plastic tube. They provide a larger lumen for swallowing and do not require as much dilatation as semirigid stents such as the Nottingham tube. As a result insertion is safer. Expanding metal stents may be inserted at endoscopy, by radiological screening or by a combination of both methods. They are produced in both covered and uncovered formats.

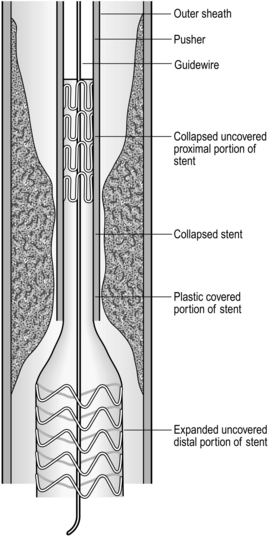

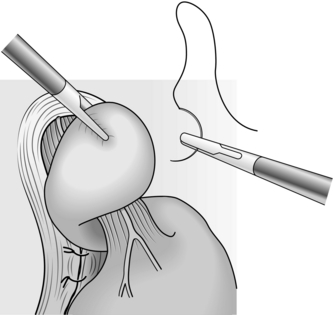

Insertion of self-expanding metal stent (Fig. 8.2)

1. There are many different designs. Be familiar with the stent, its introducer and the method of deployment. Most expanding stents shorten as they expand and this must be taken into account during insertion. Some stents can be partially deployed and the position adjusted if it is not satisfactory. However, you may have to get it right first time, so be careful.

2. Such stents can be inserted under fluoroscopic or endoscopic control. Fluoroscopy has the advantage of outlining the length and position of the stricture accurately by using a radio-opaque contrast swallow prior to insertion. Dilatation up to 1 cm is usually required prior to stent deployment, as described above for dilatation of difficult strictures.

3. Pass the stent with its introducer over the guidewire and into the desired position. An endoscope may be passed alongside the guidewire so that deployment can be checked under vision.

4. Deploy the stent according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

5. Correct stent deployment can be checked by endoscopy or contrast swallow. Some stents may be very slow to expand. Expansion may be hastened by dilatation with a through-the-scope balloon.

Aftercare

1. Make sure the patient does not have chest pain, air emphysema in the neck, or a raised temperature. Have a plain chest radiograph taken or perform a contrast swallow.

2. If there is evidence of a leak, confirm it and identify the site with X-rays using a water-soluble contrast medium. If an expanding stent is not sealing a leak consider inserting a second stent. Start the patient on broad-spectrum antibiotics and withhold food and fluids until the patient is entirely comfortable and a contrast swallow shows no leak.

3. Following stent insertion, warn the patient against swallowing unchewed food, particularly lumps of meat, fruit skins and stones, and to wash down the food with sips of water. Aerated drinks such as sodium bicarbonate solution (half a teaspoonful in half a glass of water half an hour before meals) or fresh pineapple juice help to wash away adherent mucus that may block the tube.

4. It is now extraordinarily uncommon to fail to intubate a tumour. If it cannot be done, a feeding gastrostomy or jejunostomy may be inserted after full discussion with the patient. This poses ethical and philosophical dilemmas, but these must be faced. However, always remember that the aim of palliation is to improve the quality of remaining life. If a particular therapy will not improve the quality of life in an individual patient, do not use it.

OESOPHAGEAL EXPOSURE

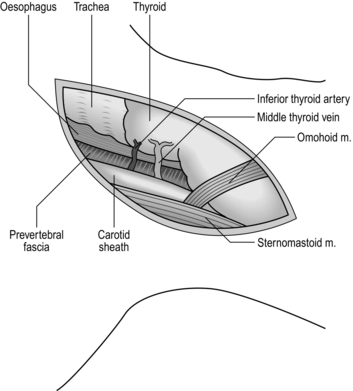

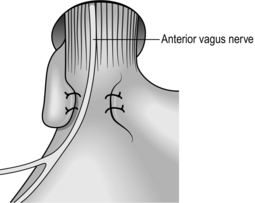

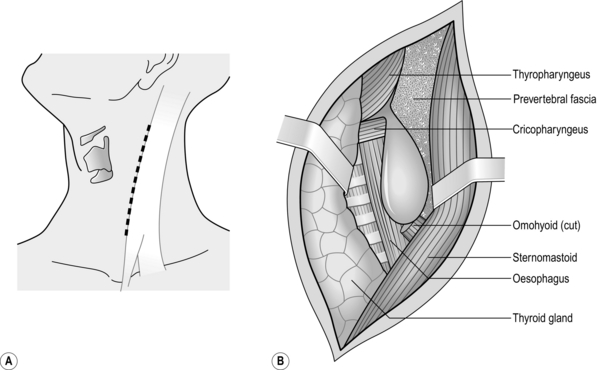

NECK (Fig. 8.3)

1. The cervical oesophagus may be approached from either side. Operations for the removal of pharyngeal pouch and cricopharyngeal myotomy, are usually carried out from the left side. For oesophageal anastomosis following resection, either side can be used. The right-sided approach minimizes risk of damage to the thoracic duct, although this is a rare complication for exposure of the oesophagus and usually occurs as a complication of biopsy of lymph nodes. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve is more likely to be injured during intrathoracic resection or be involved in the malignant process. It is better, therefore, to expose it to risk of injury rather than the right nerve.

2. The anaesthetized intubated patient lies supine on the operating table with the head turned to the opposite side from which the exploration will be made, resting on a ring with the neck extended. There is no need for complex head towelling, but drapes can be secured with skin staples.

3. Incise along the anterior border of sternomastoid muscle, through platysma muscle, cervical fascia, omohyoid muscle, ligating and dividing the middle thyroid vein to enter the space between the oesophagus, trachea and thyroid gland medially and the carotid sheath laterally. The inferior thyroid artery crosses the space; ligate and divide it laterally only if it interferes with the dissection.

4. Rotate the whole oesophageal-tracheal-thyroid column towards the opposite side, bringing into view the trachea-oesophageal groove, and display the posterior surface of the oesophagus and lower pharynx. Beware of inserting a Langenbeck’s retractor into the trachea-oesophageal groove since it may well crush the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

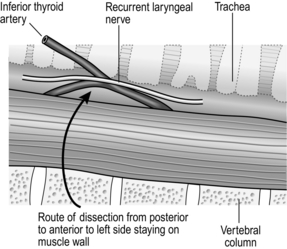

5. Mobilize the posterior wall of the oesophagus with blunt dissection. Staying on the muscle wall of the oesophagus, come anteriorly and over the front, separating the trachea and recurrent laryngeal nerve anteriorly (Fig. 8.4). It is not necessary to mobilize the nerve and this prevents an ischaemic neuropraxia. Staying on the muscle wall, go round the oesophagus on the opposite side, retracting the oesophagus laterally. This exposes the prevertebral fascia on the opposite side. A curved forceps can then be placed around the oesophagus and a sling placed. With gentle traction on this, the oesophagus can be mobilized by finger dissection, staying on the oesophageal wall.

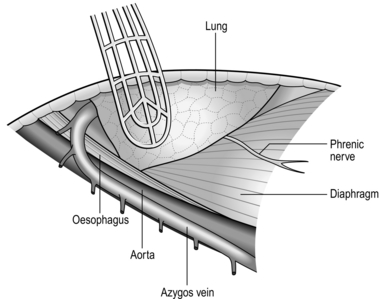

RIGHT POSTEROLATERAL THORACOTOMY (Fig. 8.5)

1. The anaesthetized patient, intubated with a double-lumen tube to allow exclusion of the right lung, lies on the left side. Carry out right posterolateral thoracotomy at the level of the fifth or sixth rib.

2. Ask the anaesthetist to collapse the right lung. Draw it downwards and forwards to reveal the mediastinal pleura. The oesophagus cannot be seen but the azygos vein can be seen arching over the lung root. Incise the mediastinal pleura, mobilize, doubly ligate and divide the azygos vein. This reveals the oesophagus running posterior to the trachea and lung root. The lower oesophagus is not visible between the left atrium and the vertebral column as it veers to the left. Expose it by dividing the pulmonary ligament until the inferior pulmonary vein is exposed. Then divide the mediastinal pleura anterior to the descending aorta. The upper stomach can be approached after dilating or incising the diaphragmatic crus to enlarge the hiatus.

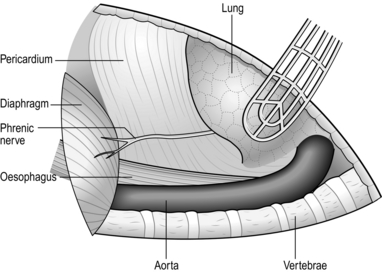

LEFT THORACOABDOMINAL APPROACH (Fig. 8.7)

1. The lower thoracic oesophagus and upper stomach are best approached using a combined thoracoabdominal approach.

2. Lay the anaesthetized intubated patient on the right side, left leg extended, right leg flexed at hip and knee, both arms flexed with forearms before the face. Allow the patient to lie back with the shoulders at 30° from the vertical. Fix the patient’s hips with an encircling band; support the left upper scapula against a padded post.

3. Prepare the skin and drape the area with sterile towels.

4. Start the incision 2.5 cm under the right costal margin in the midclavicular line, carry it obliquely upwards and to the left to cross the costal margin along the line of the seventh or eighth rib, extending to the posterior angle of the chosen rib and up behind the scapula. Deepen the incision to enter the thorax along the line of the rib, cutting and removing 1 cm of the costal margin. Incise the diaphragm peripherally parallel to the chest wall far enough in to enable the chest to be opened but not as far as the hiatus. This method spares the phrenic nerve.

5. In case of doubt make the abdominal or thoracic part of the incision first; assess the condition and now, if indicated, extend it fully.

6. After completing the procedure, close the diaphragm with strong absorbable material. Do not suture the costal margin but resect a wedge of cartilage to enable the ends to lie adjacent. Suture the abdomen in the usual manner. Close the chest after inserting an underwater-sealed drain.

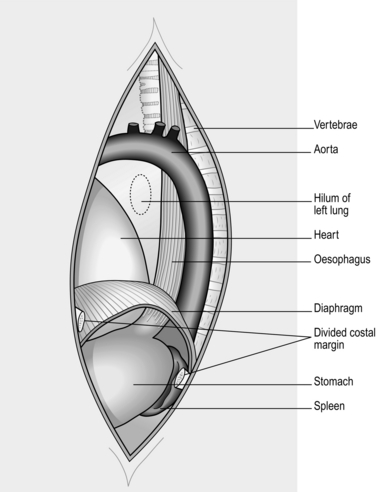

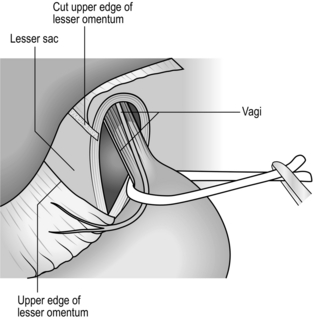

ABDOMINAL APPROACH (Fig. 8.8)

1. The lower oesophagus is approachable through the abdomen and oesophageal hiatus.

2. The best access, especially in patients with a wide costal angle, is by a roof-top or bilateral subcostal incision. In those with a narrow costal angle an upper midline incision extending to the costal margin is preferable, opening the peritoneum just to the left of the falciform ligament. Ligate the ligamentum teres. Divide it and the falciform ligament.

3. Draw down the stomach while an assistant elevates the left lobe of the liver with a flat-bladed retractor. The lower oesophagus can be felt at the hiatus.

4. If necessary, cut the left triangular ligament and fold the left lobe of the liver to the right.

5. To display the lower thoracic oesophagus, transversely incise the peritoneum and fascia over the abdominal oesophagus for 5 cm, preserving the anterior vagal trunk. If greater exposure is necessary, insert a finger into the posterior mediastinum. Turn it forwards to separate the pericardium from the upper surface and incise the crus and diaphragm anteriorly for 5–7 cm. In patients of suitable build, the oesophagus can be viewed almost up to the carina of the trachea if the heart is gently elevated with a flat retractor. It is usually unnecessary to close the incision in the crus and diaphragm. The inferior phrenic vein will need to be oversewn.

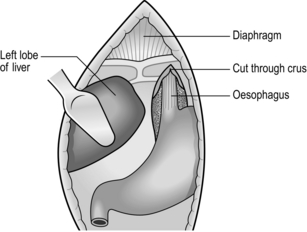

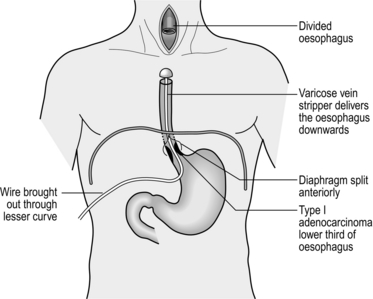

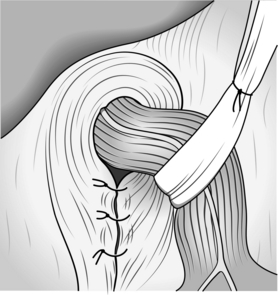

TRANSHIATAL APPROACH (Fig. 8.9)

1. This encompasses both the abdominal and cervical approaches described above.

2. After division of the diaphragm anteriorly, dissect the fat pad off the back of the pericardium. It is common to take the pleura on the left side. Place an anterior resection retractor behind the heart and lift up and towards the head. Take care not to compress the left atrium. Dissect under direct vision to the carina using a harmonic scalpel, dividing the vagi.

3. Mobilize the oesophagus in the neck as described from the left side. After encircling the oesophagus, mobilize it with a finger into the upper mediastinum.

4. Place a tie around the oesophagus low down and produce a mucosal tube as described below. Open the anterior part of the mucosal tube and withdraw the nasogastric tube. Grasp the end of the nasogastric tube and place a tie into it to facilitate bringing it back to the conduit during the anastomosis.

5. Pass the wire of a varicose-vein stripper into the oesophagus and pass it into the stomach. Tighten the tie round the stripper wire distal to its insertion and divide the oesophagus. Place a medium head on the stripper. Gently pull the stripper distally, guiding the head into the posterior mediastinum avoiding damage to the adjacent structures. This will invert the oesophagus and deliver it to the abdomen. Vagal strands may prevent full delivery and need division under direct vision from below.

6. To guide the conduit to the neck for anastomosis use a chest drain to avoid rotation.

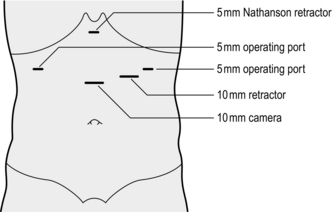

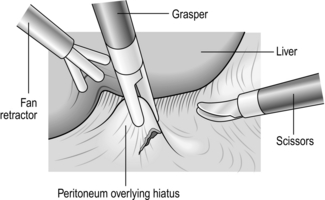

LAPAROSCOPIC APPROACH

1. Position the patient supine with the legs flat (for diagnostic or staging endoscopy) or with the legs apart in stirrups, as in rectal surgery (for major procedures, such as antireflux surgery).

2. Induce a pneumoperitoneum using a Veress needle or by an open technique.

3. Insert a 10-mm cannula in the midline approximately one-third of the distance between the umbilicus and the xiphisternum.

4. Liver retraction is best achieved by use of a Nathanson retractor inserted via a small 5-mm incision in the epigastrium. If not available, insert a 5- or 10-mm cannula, depending on what type of liver retractor is used, in the right subcostal region in the midclavicular line. Introduce a liver retractor and lift the left lobe of the liver upwards.

5. The number and position of additional cannulas depend on the procedure to be done and the preference of the operator. Commonly, additional cannulas are placed below the xiphisternum, in the left subcostal region in the midclavicular line and the anterior axillary line (the ‘Liege’ approach).

6. The oesophagus may then be approached as described in the previous section by dividing the peritoneum over the lower oesophagus. The precise approach to the oesophagus depends on the procedure to be done.

OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Appraise

1. Most other parts of the bowel are covered with serosa which rapidly forms fibrinous adhesions, sealing small defects and preventing leaks. The oesophagus has no serous coat except on the anterior wall of the abdominal segment.

2. A considerable part of the oesophageal wall is composed of longitudinal muscle. Longitudinally placed sutures thus have a tendency to cut out. The powerful longitudinal muscle produces shortening of the transected oesophagus when it contracts. Unless this is allowed for, the most carefully placed sutures may be torn out.

3. When the oesophagus is completely relaxed it has a remarkably large lumen. Commonly, the action of the circular muscle makes the diameter appear to be small. However, it can be stretched quite easily by insertion of a Foley catheter and inflating the balloon to facilitate the placement of sutures. If this is not done, closely spaced sutures may become widely separated on stretching, and leakage can easily occur between them.

4. The blood supply to the oesophagus is tenuous when it is mobilized, especially at the lower end.

5. The healthy oesophagus is easily damaged but disease may make it exceptionally fragile.

6. A diseased or partially obstructed oesophagus is contaminated. Prophylactic antibiotics must be given to cover the operation.

7. Although oral feeding may be stopped temporarily following oesophageal surgery, swallowed saliva must still pass through.

8. Intrathoracic oesophageal leakage produces posterior mediastinitis and if the pleura is damaged a pleural collection develops. The best hope for the patient’s survival if major leakage occurs is rapid clinical recognition with early re-operative repair and drainage. Minor leaks may be treated conservatively. Place chest drains in all opened chest cavities. Following transhiatal resection, even if the pleura is not opened a chest drain in the posterior mediastinum will prevent haematoma collection. A feeding jejunostomy should be placed at operation in all cases for postoperative nutrition and oral intake should not commence until the anastomosis is checked by contrast swallow at 5 days.

Anastomosis

1. The tenuous blood supply of the oesophagus makes it rarely possible to excise a segment, mobilize the cut ends and carry out an end-to-end union, except in neonates. Anastomosis is therefore usually to stomach, jejunum or colon.

2. Sutured anastomoses have been described using many different methods and materials. It is now recognized that single-layer anastomoses with continuous or interrupted sutures are best.

3. Circular stapling devices are often useful. Do not assume that perfection automatically follows their use. As with sutures, staplers give results commensurate with the care with which they are used. Which to choose? The stapling device saves a little time. It may allow an anastomosis to be accomplished where suturing is difficult high in the abdomen, under the aortic arch, or high in the thorax; but if it fails, suturing is usually impossible and a higher resection is necessary. The stapling gun has an inevitable crushing effect on the tissues. If a dilated and thickened oesophagus is to be joined to the cut end of bowel, the resulting tissue bulk cannot be accommodated in the staple gun. It is safer to use a sutured anastomosis. Hand suturing is usually preferable in the neck since there may be insufficient bowel accessible below the anastomosis for insertion of the gun.

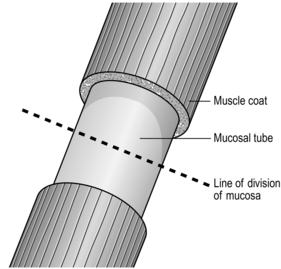

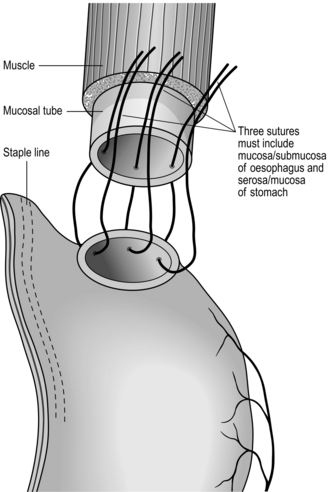

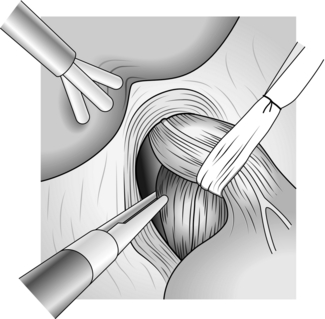

Sutured anastomosis

1. Have you made sure that the oesophagus and conduit, which may be stomach, jejunum or colon, can be joined without tension and are not twisted? When the oesophagus contracts the powerful longitudinal muscle causes remarkable shortening. However, longitudinal muscle is of little value in retaining sutures, which easily cut out between the muscle fibres, so the strength of the anastomosis must depend upon the submucous coat and to some extent on the mucosa. To achieve this, when dividing the oesophagus first divide the muscle coat to produce a mucosal tube 1 cm long. Divide this in the middle with one cut, leaving the mucosa/submucosa pouting and associated with a little ooze. This is the layer that must be used for the anastomosis (Fig. 8.10).

2. Make sure the hole in the conduit matches the oesophageal lumen when it is slightly stretched. Place the oesophagus and conduit together as they will lie when joined. Avoid traction stitches as they can produce tears in the oesophageal walls. The ends should lie adjacent with no tension.

3. Suture material should be absorbable, such as polyglycolic acid, monofilament polyglyconate, polydioxanone or braided polyglactin 910 or braided lactomer 9–1. Use fine material such as 3/0.

4. The argument about continuous versus interrupted stitches continues. Good surgeons obtain good results with both methods. Continuous stitches, having fewer knots that weaken the thread, can, if inserted as an unlocked spiral, appose the tissues accurately without constricting them. Interrupted sutures tied without tension have the advantage that, if one cuts out, those on either side are not necessarily prejudiced. The choice is personal, often the result of following the tenets of an admired teacher. If you use interrupted stitches, those uniting the posterior walls are tied within the lumen, those uniting the anterior walls are tied on the outer walls.

5. For interrupted sutures, place three loose full-thickness sutures at the middle of the back wall and the angles 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock (Fig. 8.11). Insert further sutures, usually between two or three, again loosely. Make sure that there are no gaps and the sutures include the mucosal layer. When the back wall is complete, tie the sutures, leaving those at the angles long. Ask the anaesthetist to pass a nasogastric tube into the conduit and secure. The anterior layer of full-thickness sutures is now placed with knots on the outside. For continuous sutures it is best to use a double-ended monofilament suture and start at the middle of the back wall. Initial sutures can be placed loose and then tightened. Working from both sides, complete the back wall and introduce the nasogastric tube as before. Complete the anterior wall and tie the suture. Buttress sutures should be avoided; they narrow the lumen and can produce ischaemia.

6. As you draw stitches taut and tie them, remember that there will be some swelling of the tissues within the next few hours. If you have pulled the sutures too tight, they will cut through. Concentrate on placing each suture perfectly. Prefer to cut out and replace any that you are not satisfied with, rather than inserting extra ‘bodging’ stitches that may merely damage the blood supply. At the end, gently rotate the anastomosis to examine it, but remember that even more important is the integrity of the mucosal apposition.

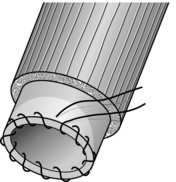

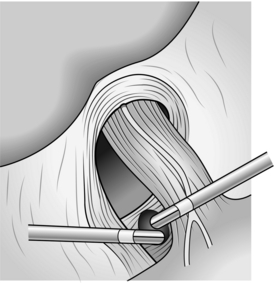

Stapled anastomosis

1. Make sure that the oesophagus and bowel can be joined together without tension, are not twisted and that both ends have a good blood supply.

2. Transect the oesophagus, muscle first and the mucosa as described above. Insert a purse-string suture using 2/0 Prolene with an over-and-over suture encompassing the mucosal/submucosal layer (Fig. 8.12).

3. Assess the size of the oesophageal lumen by gently opening the jaws of an empty swab-holding forceps. Select the largest size of stapler that easily fits the lumen. Do not attempt to force in a larger head as this will split the oesophageal wall. For a non-obstructed oesophagus a 25-mm head usually fits best.

4. Open the circular stapling device to its maximum extent, separate the anvil from the spindle and then retract the stem by ‘closing’ the gun without the anvil. Introduce the anvil into the lower oesophagus. Tipping the anvil sideways may make introduction easier if it is a snug fit. Tighten and tie the previously inserted purse-string suture. Check that the purse string has drawn the oesophagus close to the stem. If there is a gap, insert a second purse string.

5. If the stomach is to be used, create a temporary anterior gastrotomy and insert the spindle of the stapler into the fundus at least 2 cm from any suture or staple line. ‘Open’ the instrument so that its sharp point comes through the stomach (Fig. 8.13). If the jejunum or colon are joined end-to-side, insert the stapler without the anvil head through the cut end; this will be closed later. Protrude the stem through the antimesenteric wall at a suitable point.

6. Attach the anvil on its spindle to the instrument and bring together the conduit and the oesophagus by closing the anvil down on to the cartridge. Check that there is no twisting and that nothing is interposed, nothing is protruding.

8. Compress the handles fully and firmly: if using the Ethicon stapler a definite crunch will be felt. The gun has now been ‘fired’.

9. Separate the jaws slightly. Gently rotate the device and draw it clear of the stapled anastomosis. Completely withdraw the instrument.

10. Remove the anvil head and check the toroidal (‘doughnut’-shaped) oesophageal and viscus cuffs trimmed from the inside of the anastomosis. Make sure they are complete and then place them in fixative solution prior to histological examination.

11. Insert a finger through the anastomosis to check it. If an aspiration tube is to be passed, ask the anaesthetist to pass it now and guide it through the anastomosis with a finger.

12. Close the opening through which the instrument and finger were passed.

13. Carefully check that the anastomosis is complete all the way round and lies without tension.

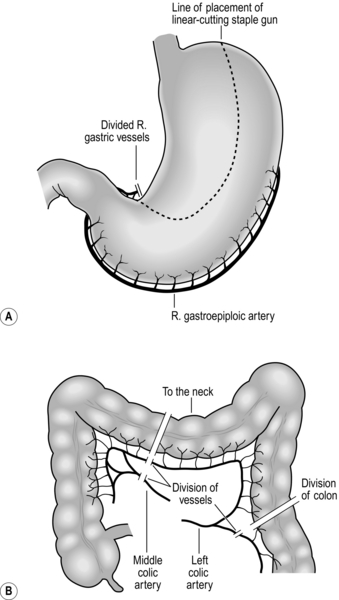

OESOPHAGEAL SUBSTITUTES (Fig. 8.14)

Fig. 8.14 Gastric and colonic oesophageal substitutes and the vascular pedicles on which they are based.

1. The alternatives are stomach, colon or jejunum. Jejunum is only applicable to anastomoses to the lower one-third of the oesophagus in most patients.

2. Both right and left colon can be used. Advocates exist for both, but the best is transverse and left colon based on the ascending branch of the left colic artery. The dogma that there is a vascular watershed at the splenic flexure is (usually) false, although the left colic artery may be stenosed or occluded in elderly, atherosclerotic patients, particularly those with aortic aneurysm. Provided there is a good marginal artery it is possible to mobilize a length of bowel, which will reach to the floor of the mouth. The right colon is bulky and more difficult to straighten. Either colon should be placed isoperistaltically.

3. The stomach is the favoured conduit due to its good vascular supply and adequate length. The conduit is based on the right gastroepiploic artery. The conduit should be a narrow tube 3–4 cm wide based on the greater curvature extending from the fundus to the lesser curve 3–4 cm proximal to the pylorus.

GASTRIC MOBILIZATION

Action

1. Identify the right gastroepiploic artery on the greater curvature of the stomach. Divide the greater omentum outside this arcade. This is best achieved with a harmonic scalpel. Continue this mobilization proximally toward the pylorus taking care not to damage the vessel at its origin where it leaves the gastric wall. Continue dissection towards the fundus of the stomach dividing the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels and taking care not to damage the spleen. Dissection is continued to the left crus dividing small vessels to the stomach arising from the splenic artery.

2. The stomach is elevated to display the posterior gastric wall and left gastric pedicle. It is best to do a flush left gastric ligation removing all associated lymph nodes, including those on the common hepatic artery. Dissection is best achieved with bipolar scissors starting on the upper border of the pancreas. The left gastric vein is encountered first and ligated and divided. The left gastric artery is frequently 1 cm behind this and to the right. This should be double-ligated flush to the coeliac axis. The dissection is then continued to the crura which are cleaned of fat and lymphatics.

3. The right gastric artery is divided 3 cm from the pylorus and the gastric tube formed with a series of ‘fires’ of a TLC 100 linear cutting staple gun. This can be oversewn with a continuous running suture if required. The duodenum is Kocherized to complete mobilization. The gastric tube is usually fashioned in the abdomen and can be hitched to the oesophageal remnant to deliver to the chest or to a chest drain if it is to be delivered to the neck to avoid rotation. Except in cases of pyloric stenosis due to previous duodenal ulceration, there is no need to perform a pyloroplasty.

COLONIC MOBILIZATION

Action

1. Prefer the left colon. Mobilize it by dividing the peritoneum to the left from sigmoid to splenic flexure. Dissect the greater omentum from the colon. The colon can then be elevated and transilluminated to display the blood vessels. The marginal artery can be well visualized. Divide this distal to the ascending branch of the left colic and divide the colon with a linear cutting staple gun.

2. Continue the dissection of the vascular supply proximally, taking care with the middle colic artery which may divide just above its origin. Identify the proximal site of division of the colon and transect the colon with a linear cutting stapler and divide the marginal artery. If you doubt the viability then apply vascular clamps before dividing it.

3. Restore colonic continuity between proximal transverse and distal descending colon.

ROUTE OF RECONSTRUCTION

1. The best route for reconstruction is via the oesophageal bed in the posterior mediastinum. Alternatives include substernal and subcutaneous routes for neck anastomoses.

2. Use the substernal route with great caution if the colon is the conduit, since it is compressed at the root of the neck, resulting in venous congestion and conduit failure. If you employ this route you should resect the manubrium and first rib to prevent this.

LYMPHADENECTOMY

1. Controversy exists regarding the extent of lymphadenectomy in oesophageal cancer surgery. There is now no role for palliative resection leaving macroscopic disease. Remove all obviously involved nodes with the specimen.

2. As described above, perform coeliac lymphadenectomy as part of gastric mobilization. For transthoracic mobilization and anastomosis, take the para-oesophageal lymphatics with the specimen.

3. For operations through the right and left chest remove the subcarinal glands for accurate staging and, if approaching via the right chest, you can remove the thoracic duct. This involves dissecting along the azygos vein to the hiatus, taking all the tissue between the vein, vertebral column and aorta. The duct can be clearly seen in this tissue; double-ligate it at the lower end to prevent chylothorax. If you do not formally dissect it out, for safety place a suture at the level of T10 to encompass all the tissue between aorta, vertebral column and azygos vein after oesophageal mobilization.

TRAUMA, SPONTANEOUS AND POSTOPERATIVE LEAKS

Appraise

1. Swallowed foreign body, stab or missile wounds may immediately rupture the oesophagus, but crush injuries such as those sustained in road traffic accidents may cause necrosis with late rupture. Uncoordinated retching may tear the lower oesophagus, usually just above the hiatus, to the left side; this is Boerhaave’s syndrome of ‘spontaneous’ or postemetic rupture. In some cases the tear is partial thickness, involving mainly mucosa, sometimes extending into the gastric cardia and presenting with acute haemorrhage. This is the Mallory-Weiss syndrome and it responds almost always to conservative management.

2. Iatrogenic rupture may follow endoscopy, dilatation of stricture or achalasia, removal of a foreign body, or follow an operation on the oesophagus including cardiomyotomy, vagotomy and resection or bypass.

3. The history of events, complaint of pain, collapse after injury or operation, presence of air emphysema in the neck and on plain radiographs demand radiological study with barium to determine the site, extent and localization of leakage. Barium gives much better imaging than water-soluble contrast and is perfectly safe. Modern water-soluble contrast media are relatively safe, but Gastrografin is hypertonic and should never be used. It is particularly dangerous if aspirated into the trachea. If these tests are negative and suspicion still exists perform endoscopy.

4. Late presentation may produce signs of cellulitis including mediastinitis, pleural effusion, empyema, peritonitis, abscess formation and fistula.

5. Following accidental or violent injury, assess the possibility of other injuries that must be dealt with.

6. Small cervical leaks following instrumental damage usually seal if the patient is fed parenterally for a few days.

7. Treat conservatively tears in the thoracic oesophagus that are: detected early, produced at endoscopy or instrumentation, associated with minimal contamination and are contained in the mediastinum. Confirm that the mediastinal pleura is intact with X-rays, using barium. If the mediastinal pleura is breached or if the patient’s condition deteriorates following initial conservative treatment, explore the leak. In general, postemetic rupture should be treated surgically as there is significant contamination of the mediastinum.

8. Intrathoracic leaks have a high mortality rate if not treated promptly. The worst results occur if the diagnosis is overlooked and the patient is fed.

9. If the oesophagus is split during dilatation of a carcinoma, immediate treatment is required: either resection or placement of a covered self-expanding metal stent. Remember that such tumours will present as advanced disease with limited life-expectancy.

CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT

1. Stop oral drinking or feeding.

2. Introduce a nasogastric tube into the stomach under X-ray screening.

3. Institute parenteral fluid replacement and feeding. For a minor leak in a fit patient, fluid and electrolyte replacement may suffice.

4. Administer broad-spectrum antibiotic cover and intravenous proton-pump inhibitors.

5. Do not place a self-expanding metal stent to seal the perforation other than in cases of established cancer. They will not seal the leak and inhibit healing.

6. If the general condition of the patient does not deteriorate, repeat the radiological examination after 7 days. Do not hurry to repeat the examination. This does more harm than good. If the leak is sealed, restart clear fluids orally, proceeding to all fluids, soft solids and full diet.

7. If the mediastinal pleura is breached so that contrast flows into the pleural space, or if the general condition of the patient deteriorates following initial conservative management, explore the leak without delay.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Access

1. Left thoracotomy gives good access to the lower oesophagus, right thoracotomy to the mid- and upper oesophagus.

2. If you suspect abdominal injuries use a left thoracoabdominal incision or be prepared to explore the abdomen subsequently.

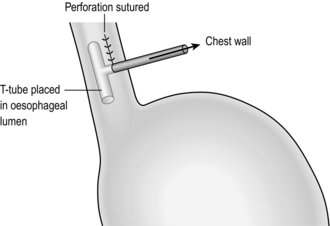

3. If this is a postoperative leak, good drainage and placement of a T-tube into the hole may suffice (Fig. 8.15). If not, then resection; you should perform proximal oesophagostomy and gastrostomy, with later reconstruction. Local debridement and re-anastomosis invariably fails.

4. Expose the oesophagus adequately to allow full assessment of the damage to the oesophagus and related structures.

Assess

1. Is there only a single site of damage? Can you identify healthy mucosa around the whole circumference? If not, extend the hole in the muscle until you can.

2. Are the tissues healthy or ischaemic? Closing defects with unhealthy margins is doomed to failure.

3. Can the defect be repaired? Is there enough tissue for closure without tension?

4. Is there any foreign material? If so, remove it.

5. What is the condition of adjacent structures? Ensure that only healthy tissues remain.

6. If this is a postoperative leak, is the cause evident? What can be learned for future incorporation in your technique?

7. Take a specimen for culture of organisms and tests for antibiotic sensitivity.

Action

1. Remove any foreign material and excise dead or doubtful tissue.

2. Small tears of the cervical oesophagus need no sutures, but it is wise to drain the area. If the tear is large it may be sutured if good access can be obtained. Alternatively, insert a drainage tube through the tear to produce a controlled fistula. Tears of the ‘cervical oesophagus’ are usually tears of the lower pharynx or perforation of an unexpected pharyngeal pouch.

3. If the defect can be repaired with simple sutures, close it in a single layer using absorbable sutures in one or two layers. Reinforce this if possible with an intercostal muscle flap, a flap of diaphragm or pericardium. Lower oesophageal holes may be reinforced by wrapping with gastric fundus.

4. If the defect cannot be repaired, it may be possible to close it by mobilizing the gastric fundus and suturing the seromuscularis around the margins of the defect. Alternatively, insert a T-tube into the leak to produce a controlled fistula, or resect the oesophagus and perform cervical oesophagostomy and gastrostomy. Reconstruction may be delayed for weeks or months.

5. Facilitate enteral feeding below the leak by performing a jejunostomy.

6. In desperate circumstances isolate a severe leak by disconnecting the oesophagus above and below it, either as a temporary or a permanent measure. Transect the oesophagus in the neck leaving the lower cut end open and bring out the proximal end to the skin as a temporary cervical oesophagostomy. Transect the oesophagus below the leak using a 55-mm staple gun. The isolated segment of oesophagus will produce only a little mucus, which will drain by the open upper end. Never perform an oesophageal anastomosis in an unstable patient. Delayed reconstruction is safer.

Closure

1. Insert underwater-sealed drains to apex and base of the pleural cavity after thoracotomy. One of the drains should be sutured in place in the mediastinum close to the leak.

2. Insert closed suction drains into the neck or mediastinum and upper abdomen if the leak or site of trauma has been approached through the abdomen and hiatus.

3. If you decide to drain a leak, defunction the oesophagus and allow the hole to close spontaneously; place a soft drain close to the hole. If it lies at a distance from the hole, the drain will merely partially empty the large abscess cavity that will form.

Aftercare

1. Continue enteral or parenteral feeding, and antibiotics.

2. Remove chest drains when they cease to drain.

3. Monitor the patient’s recovery clinically by progress charts and plain radiographs.

4. Check the repair and healing with a screened barium swallow on the seventh postoperative day. If there is no leak, oral feeding may be started, initially with clear fluids.

5. As drains cease to discharge, remove them. If fresh collections develop, drain them. Percutaneous drainage under computed tomographic (CT) guidance may be useful for secondary collections.

CORROSIVE BURNS

Appraise

1. Corrosives are swallowed accidentally or in suicide attempts during acute depression. Classically, the greatest damage occurs at the sites of hold-up above the cricoid sphincter, at the aortic crossing and above the cardia. The substance burns the mouth, pharynx and larynx; that which passes through the oesophagus into the stomach may remain there and cause ulceration, perforation and severe stricture at the gastric outlet.

2. A particular danger in children is the swallowing of small disc or ‘button’ batteries, which may release damaging caustic contents. These must be immediately and gently removed endoscopically. It is important not to use instruments that might damage the capsule. Use a snare or dormia basket, but take care not to use excessive force.

3. The mucosa is damaged or destroyed, exposing the deeper layers to any remaining or subsequent passage of the corrosive. The wall then becomes friable and liable to rupture, especially if instrumentation is attempted. The oesophageal wall may become gangrenous and rupture spontaneously, resulting in septic mediastinitis.

4. If the oesophagus does not perforate, mucosal regeneration occurs during the next 10–14 days, but wound contraction and contracture often produce rapid and severe, sometimes long, strictures. There is a small long-term risk of carcinoma.

5. Initially exclude hoarseness, stridor and dyspnoea that suggest inhalation of the corrosive. Monitor the blood gases and carry out tracheostomy if the patient has, or develops, respiratory obstruction.

6. Exclude perforation of the oesophagus, which produces back and chest pain, and intra-abdominal perforation with pain, tenderness and guarding. Order plain X-rays of the chest and abdomen and, if necessary, chest and abdomen CT scan.

7. Do not perform a contrast swallow in the acute stage as it may be extremely painful. Early endoscopy is useful in judging the extent and severity of damage. It must be done gently with the minimum of air insufflation.

8. Start broad-spectrum antibiotic cover. Stop oral intake and institute intravenous fluid therapy with subsequent nutritional support.

9. If perforation has occurred or there is extensive necrosis, carry out emergency exploration with a view to oesophagectomy. Immediate reconstruction is not recommended and exteriorization of the surviving ends and later reconstruction with a suitable conduit is safest.

10. There is no role for steroids in this condition.

11. Do not allow the patient to swallow liquids until you, or another expert, have carried out a radiological or endoscopic examination to confirm that the passage is intact.

12. Anticipate the development of strictures. If they occur, start early treatment with balloon dilators. Do not overdilate the strictures but be prepared to repeat the procedure at gradually lengthening intervals.

13. Sometimes the strictures cannot be dilated, or they recur swiftly, demanding resection and anastomosis or bypass. Occasionally a broncho-oesophageal fistula develops, and this must be defunctioned, initially with a cervical oesophagostomy and gastrostomy. These stomata may be joined later using an isolated segment of colon.

GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Appraise

1. The continence of the gastro-oesophageal junction is maintained by a combination of anatomical and physiological factors. Elegant anatomical studies have shown a gastro-oesophageal sphincter that corresponds to the high-pressure zone that can be measured by manometry. This area is still known as the lower oesophageal sphincter, although, in reality, it is more gastric than oesophageal. The effect of the functioning sphincter is augmented by the muscle of the crura of the diaphragm and by having an intra-abdominal segment of oesophagus that is subject to a degree of external compression. The sphincter, including the diaphragm, is under integrated neurological control and relaxes during swallowing and belching. Stretch receptors in the upper stomach are responsible for relaxation of the sphincter during meals.

2. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) occurs when the function of the lower oesophageal sphincter is impaired. Oesophagitis is a complication of GORD that occurs when the lower oesophagus is exposed to irritant gastroduodenal contents long enough to overcome the normal mucosal protection mechanisms. Hiatal hernia has a variable association with GORD. In general, patients with the more severe stages of GORD with oesophagitis tend to have a hernia, but most GORD sufferers do not have a hernia and many of those with a hernia do not have GORD.

3. Careful clinical assessment remains paramount in making the diagnosis and determining its effects on the life of the patient. Endoscopy is valuable to monitor the state of the mucosa and to detect the complication of Barrett’s oesophagus, which is a premalignant condition. Norman Barrett (1903–1979), surgeon at St Thomas’ Hospital London, described the condition which was later shown to result from persistent acid reflux causing changes in the lower oesophageal mucosal cells, ulceration, strictures and eventual malignancy. If symptoms of reflux cannot be confirmed by endoscopy, 24-hour lower oesophageal pH recording is useful. Assessment of GORD and its complications by radiology is inaccurate and therefore plays little part.

4. The symptoms of reflux may be confused with many disorders causing dyspepsia. Always make an objective diagnosis if surgery is considered.

5. Uncomplicated reflux can frequently be managed without surgical treatment. Many patients are overweight. The worst sufferers are sometimes those with good abdominal muscles, such as ex-sportsmen, who subsequently lay down fat that is not obvious, increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Sensible weight loss may cure the symptoms. Smoking, alcohol and fatty foods aggravate the symptoms and are best eschewed. Simple antacid or antacid/alginate preparations may help, but will have been tried long before the patient reaches a surgeon. H2-receptor antagonists will likewise often have been prescribed. Undoubtedly the most effective medication is a proton-pump inhibitor. Omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole all have similar effects, although newer drugs such as esomeprazole have a longer duration of action and higher healing rates especially in grade 3 and grade 4 oesophagitis.

6. Consider operation if severe symptoms continue in spite of compliance with medical advice. Be wary of those who will not attempt to lose weight; they frequently put on more weight after operation. Of course, some patients cannot, for a variety of reasons, adhere to an effective regime. Warn the patient that the best reported results are about 85% excellent or good, and that 15% therefore still have symptoms. Be particularly wary of patients who continue to have dyspeptic pain during treatment with an adequate dose of a proton-pump inhibitor. The pain is highly likely to persist after surgery. If in doubt about the effectiveness of a given dose of proton-pump inhibitor, perform 24-hour monitoring of oesophageal and gastric pH to check that acidity is suppressed.

7. The best indication for surgery is persistent regurgitation (volume reflux). This responds poorly to medication and can be remarkably disabling. Beware of offering surgery to patients whose symptoms are well controlled on medical treatment.

8. Barrett’s oesophagus is the result of reflux and seems to be increasing in incidence. The role of antireflux surgery in Barrett’s oesophagus is still unknown. Patients with Barrett’s require regular endoscopic surveillance. If persistently severe dysplasia or neoplasia develops then carry out oesophagectomy if the patient is fit enough to withstand it.

9. The most popular antireflux operation is the Nissen circumferential fundoplication. This can be performed by conventional open or laparoscopic surgery through the abdomen. The postoperative result may be marred by dysphagia, ‘gas bloat’ or change in bowel habit. The operation has been modified to avoid this, by making a short and loose (‘floppy’) fundic wrap or by performing a 270° wrap (Toupet). Other approaches such as the transthoracic Belsey are rarely used and will not be described further. There is a shift in opinion towards partial fundoplication, but good results may be obtained by either method if well done.

10. For complex cases in which there is fixed oesophageal shortening, the Collis procedure may be performed, in which a tube is formed from the upper part of the stomach. It is very rarely seen, however, and with proper mobilization the oesophagogastric junction can be brought below the hiatus in nearly all cases.

11. The vagi should never be divided deliberately as part of an antireflux operation since this risks producing postvagotomy symptoms. If the vagi are cut accidentally, as may well occur during revision operations, a pyloroplasty should not be performed. It is unnecessary and leads to additional side-effects.

12. Some patients with particularly difficult reflux problems complicating previous surgery may be helped by partial gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. However, this is not suitable for treatment of uncomplicated reflux and should not be undertaken lightly.

13. Finally, in extreme circumstances, if the cardia has been severely damaged by disease or surgery the only option may be to resect the oesophagus. Continuity may be restored by transposition of the stomach and anastomosis to the cervical or upper thoracic oesophagus, or by interposition of jejunum or colon.

14. Reflux may complicate cardiomyotomy, surgical damage to the hiatal mechanism and damage to, or resection of, the cardiac sphincter in the absence of hiatal hernia. The symptoms and effects may be disabling.

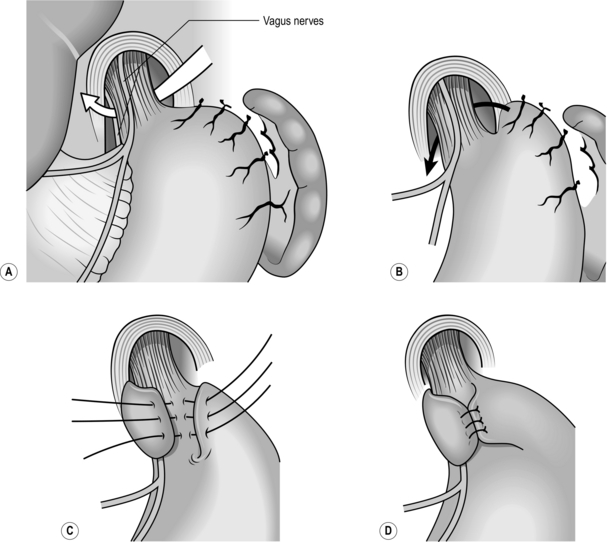

TRANSABDOMINAL FLOPPY NISSEN FUNDOPLICATION (Fig. 8.16)

Access (Fig. 8.17)

1. Elevate the head end of the operating table.

2. Use an upper midline abdominal incision, opening the peritoneum to the left of the ligamentum teres and falciform ligament. An alternative is a bilateral Kocher’s roof top incision.

3. If necessary, excise the xiphoid process.

4. Use an on-table mechanical retractor to lift the sternum and costal margin to flatten the diaphragm and give good access to the hiatal hernia.

5. Mobilize the left lobe of the liver and fold it to the right.

Assess

2. Look for a sliding hiatal hernia. If the hernia reduces easily and does not tend to spring back into the chest it is safe to proceed with the Nissen operation. It is important to note that if the hernia appears fixed, careful dissection of the oesophagus into the chest may be required.

3. In rolling hernia the gastric fundus herniates alongside the gullet into the chest. The cardia may remain in the abdomen or slide into the chest.

Action

1. Resist the temptation to approach the oesophagus as the first manoeuvre. In open surgery it is much easier to perform a Nissen fundoplication if the fundus of the stomach is mobilized first.

2. Divide most of the short gastric vessels that tether the stomach to the spleen. This is best achieved using a harmonic scalpel. There is often a second layer of vessels entering the posterior aspect of the fundus directly from the splenic artery. Divide these also.

3. When the fundus has been mobilized, continue sharp dissection around the hiatus to expose the lower oesophagus and the crural margins. Identify the anterior and posterior vagal trunks and preserve them.

4. On the right side, divide the upper portion of the gastrohepatic omentum, to display the right margin of the hiatus. Leave the hepatic branches of the vagus nerve intact, together with an accessory hepatic artery.

5. Trim the sac, consisting of stretched peritoneum and phrenooesophageal ligament, from the lower oesophagus.

Posterior repair

1. Ask the anaesthetist to pass a 50 F Maloney tapered mercury dilator into the stomach. This has a soft flexible tip and can be passed with safety.

2. Displace the gullet forwards and stitch the margins of the hiatus together behind it using 2–4 non-absorbable sutures. Leave a space between the hiatus and the stented oesophagus that will admit a finger. Take care not to overtighten the hiatus to avoid postoperative dysphagia.

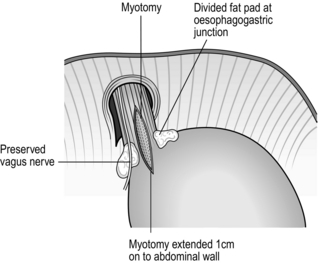

3. Excise the fat pad that lies in front of the cardia. Take care not to damage the anterior vagus when doing this. There are some surprisingly large blood vessels in the pad that must be ligated.

4. Now gently fold the gastric fundus behind the lower oesophagus so that the greater curvature emerges above the lesser curvature. The posterior vagus nerve may be included in the wrap or the wrap may be placed between the posterior vagus and the oesophagus. Both methods have their advocates and are equally acceptable.

5. The fundus of the stomach should fold around the oesophagus with ease and should lie in place when released. If it tends to retract the fundus has not been adequately mobilized.

6. Insert a non-absorbable suture, such as braided polyamide, to pick up the upper anterior wall of the stomach on the left of the oesophagus, the lower oesophagus immediately above the cardia and the part of the stomach that has been folded behind and to the right of the oesophagus. Each stitch is deep enough to incorporate the submucosa but not to pierce the mucosa. Tighten the stitch so that the two folds of stomach are brought together in front of the oesophagus. Check that a finger can be passed easily between the wrap and the oesophagus which contains the 56 F dilator. The wrap must be really floppy to avoid postoperative dysphagia and gas bloat. Insert a second stitch 1 cm above the first one. The completed fundoplication must not be more than 1 cm long anteriorly. If it is too long, there will be an increased risk of dysphagia and gas bloat.

7. Resist the temptation to insert extra stitches and hitches. They do more harm than good.

8. Ask the anaesthetist to withdraw the mercury dilator but leave the nasogastric tube.

PARTIAL FUNDOPLICATION

1. In order to reduce the incidence of dysphagia and ‘gas bloat’, many surgeons favour partial fundoplication. There are various methods, which differ in detail, but the principle is the same.

2. The wrap encircles only 270° of the lower oesophagus. To carry this out, first have the anaesthetist pass a nasogastric tube into the stomach. Mobilize the upper half of the gastric greater curve by dividing at least half the short gastric vessels. Fold the gastric fundus loosely round the lower oesophagus. Insert stitches to produce a wrap not more than 3 cm long, around the lower oesophagus. Each of usually two or three stitches picks up gastric fundus on the right and the oesophagus. A second set of two or three stitches picks up the oesophagus and the left upper stomach, leaving the anterior 90° of oesophagus bare (Fig. 8.18).

3. In the Toupet operation the hiatus is not repaired. Instead, the completed fundoplication is stitched to the crura on both sides.

LAPAROSCOPIC FUNDOPLICATION

Access

1. Place the patient supine with the legs in Lloyd-Davies stirrups as for a perineal operation.

2. Tilt the operating table 30° head up.

3. Have the anaesthetist pass a nasogastric tube to aspirate the stomach. Most surgeons now avoid the use of a 50 F Maloney dilator because of the risk of perforation.

5. Place a mixture of 5- and 10-mm cannulas as shown in Figure 8.19.

6. Place a Nathanson retractor into the epigastric port to retract the left lobe of liver and expose the hiatus.

Action

1. First expose the distal oesophagus by dividing the gastrohepatic ligament from about the level of the left gastric artery to the hiatus (Fig. 8.20).

Fig. 8.20 Division of gastrohepatic ligament.

2. Divide the ligament with a harmonic scalpel taking care to identify any vascular structures in the ligament as they can bleed. You now see the right crus of the diaphragm, even in obese patients, provided the liver and stomach are correctly retracted.

3. Now completely expose the crural structure, exposing the landmarks for safe posterior dissection of the oesophagus. Take your dissection over the top of the oesophagus and down the left crus dividing attachments between the angle of His, fundus and diaphragm. Again, a blood vessel is frequently encountered here. Use a harmonic scalpel for this (Fig. 8.21).

4. Take especial care to expose the most posterior aspect of the left crus in order to create the posterior window safely. When the crural muscular fibres are fully exposed, blunt dissection of the oesophagus can be safely accomplished from the lateral and anterior aspects.

5. If a hiatal hernial sac is present, deliver it during the exposure of the muscle fibres.

6. Prepare to create a window posterior to the oesophagus. First ensure that the posterior left crus is completely dissected; it is 1 mm wide and has a firm consistency when you feel it with your right-handed blunt grasping forceps as they sweep inferiorly, following left lateral and anterior retraction of the oesophagus. In thinner patients the posterior crus presents as a visible ridge of tissue covered by para-oesophageal fat, provided retraction is correct. The left crus can also be identified by looking for the posterior vagus nerve as it curves over the structure.

7. You are at risk of gastric or oesophageal perforation if you dissect too inferiorly to the gastric wall, or too anteriorly to the gastro-oesophageal junction.

8. Create the window from the right side, elevating the oesophagus anteriorly with a blunt forcep, and with the other hand separate any strands posteriorly with a harmonic scalpel. Use a sweeping chopstick motion with two forceps to open a window, ensuring this is below the left crus seen from the right. It is easy to dissect into the chest above the crus in this situation (Fig. 8.22).

9. When the window is opened the spleen and post wall of the fundus may be seen. In fat individuals a curved forceps can help this dissection. Attempt to make the window behind the posterior vagus, keeping it next to the oesophagus.

10. In order to secure the wrap in the abdomen, you must close the hiatus by suturing the crura together. Use a 2/0 coated, braided polyester (Surgidac) on a curved needle. Take care to avoid injuring the posterior wall of the oesophagus when you place sutures in the left crus (Fig. 8.23).

Fig. 8.23 Closure of the hiatus with sutures.

11. The right crus is thinner than the left so include its lateral peritoneal covering to prevent the stitch from tearing out. Two deeply placed stitches are usually sufficient, tied intracorporeally. It is important not to close the hiatus tightly as this will result in dysphagia.

12. Greater curvature mobilization is currently a matter of debate and is usually not required. In some circumstances it allows the consistent formation of a loose wrap. Intend to divide the gastrosplenic ligament for 10 cm from the angle of His. Have the first assistant use an atraumatic, finely serrated 5-mm grasping forceps, in order to avoid tearing fatty tissue or the short gastric vessels. You hold the stomach so that the ligament is horizontal and under tension. Divide small amounts of tissue at a time, using harmonic scalpel scissors.

13. You are now ready to perform the fundoplication. Elevate the oesophagus and, under direct vision, insert the Babcock clamp through the window until you can see it on the left side of the oesophagus. Grasp the greater curve of the stomach approximately 5–7 cm from the angle of His and draw it to the right behind the oesophagus.

14. Avoid a spiral wrap, which can include the body of the stomach in the left limb of the wrap. Carefully choose the appropriate position for the left limb suture. Try to have the limbs in continuity so that traction on one limb moves the other (Fig. 8.24).

15. Place a full-thickness suture through the stomach but include only the muscular wall of the oesophagus to avoid the risk of postoperative oesophageal leakage. Incorporation of the oesophageal suture is important because it helps to secure the wrap. Sutures can be applied using either intra or extra-corporeal techniques. Perform a short 1–2 cm loose wrap with up to three sutures. There is no need to pass a bougie as these can damage the oesophagus and cause a perforation (Fig. 8.25).

Fig. 8.25 The completed wrap.

Postoperative

1. Order a postoperative Gastrografin swallow if you encountered any difficulties, but not routinely.

2. Encourage the patient to drink fluids after 6 hours. A sloppy diet can be taken within 12 hours.

3. Most patients can be discharged home within 24 hours with instructions to maintain the sloppy diet for the first 4 weeks.

4. Have the port-site sutures removed 1 week after the operation.

ROLLING HERNIA

Appraise

1. The gastric fundus may prolapse through the hiatus alongside the oesophagus alone, or alongside a sliding hiatal hernia of the cardia. The fundus may also prolapse through a congenital or acquired defect in the diaphragm near the hiatus.

2. Sometimes the rolling hernia becomes a volvulus of the stomach as the greater curvature increasingly prolapses through the hiatus.

3. Rolling hiatal hernias should always be repaired unless there is a contraindication to an operation. If the patient develops pain, vomiting from entrapment, obstruction or volvulus, operative repair should be performed as a matter of urgency.

4. Occasionally, a patient presents as an acute abdominal emergency, nearly always having had previous less severe attacks.

Action

1. Identify the gastric fundus disappearing through the hiatus.

2. Reduce the hernia by gentle traction on the stomach. Do not use force or you will tear the gastric wall.

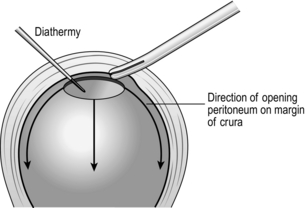

3. When you have completely reduced the stomach, it is very important to excise the sac, thus exposing the crura. This is best achieved by placing a Roberts forcep at the apex of the hiatus and, using long-handled diathermy, incising the peritoneum and carrying it around the margin mobilizing the sac, which by gentle finger dissection can be mobilized from the chest (Fig. 8.26). The sac is then excised and the whole circumference of the oesophagus is carefully examined by rotating it.

4. In emergency operations for what is in these circumstances often a strangulated hernia, the gastric wall constricted in the crus may be gangrenous in places. Do not immediately get carried away with the desire to carry out a resection. The blood supply is usually intact proximal and distal to the constriction ring. If it is, invaginate the linear gangrenous ring with a running deep seromuscular stitch.

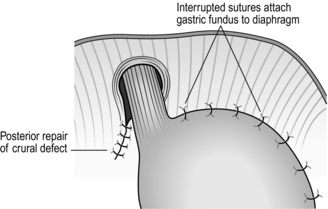

5. Carry out repair of the defect by uniting the crura posterior to the oesophagus, using four or five non-absorbable mattress sutures.

6. Some surgeons insert three or four non-absorbable sutures that fix the gastric fundus to the undersurface of the left diaphragm – a ‘fundopexy’ (Fig. 8.27).

7. Alternatively, a fundoplication may be performed. Although there is controversy about the need for an antireflux operation, in these circumstances it seems to do little harm, provides good fixation for the stomach and deals with concurrent reflux symptoms. A gastrostomy on the greater curve also fixes the stomach and acts as a vent.

LAPAROSCOPIC REPAIR

Action

1. Elevate the left lobe of the liver and identify the hiatus and the herniated stomach.

2. Gently reduce the stomach into the abdomen.

3. The operation is greatly facilitated by early excision of the hernial sac. Divide the sac at the hiatal margin, pull down and excise the sac, taking care not to damage the vagi.

4. Repair the crura posterior to the oesophagus.

5. Some prefer to insert a mesh into the hiatus anteriorly to avoid suturing the crura under tension.

6. Fix the stomach in the abdomen with a fundoplication, if preferred.

SIMPLE LAPAROSCOPIC GASTROPEXY

Appraise

1. Many patients with rolling hiatal hernia are elderly, frail and unfit. They may be severely symptomatic, but not fit for major surgery.

2. If the hernia can be reduced and the stomach straightened out, the symptoms of a rolling hernia are relieved and the risk of gastric volvulus is avoided.

3. Simple laparoscopic gastropexy involves minimal surgical trauma and produces surprisingly good results.

Access

1. Place the patient supine with the legs elevated if it is safe to do so. Otherwise operate on the supine patient with the head of the table elevated.

2. Induce a pneumoperitoneum and place cannulas in the following positions: midline above the umbilicus one-third of the distance between umbilicus and xiphisternum; right subcostal, midclavicular; upper midline, below the left lobe of the liver so that the stomach can be sutured to this port site; left subcostal, midclavicular; left subcostal, anterior axillary.

3. Gently reduce the stomach into the abdomen.

4. Insert a non-absorbable suture through the upper midline port leaving the tail of the suture outside the abdomen. Gore-Tex is ideal for this purpose. Take a generous seromuscular bite of the upper stomach at a point that will maintain reduction of the stomach and allow it to be drawn up to the port site when the suture is tied. Bring the needle out of the port and leave the ends long and leave the needle in place.

5. Repeat the above manoeuvre with a suture passed through the left subcostal port.

6. When the sutures have been placed satisfactorily, remove the cannulas and deflate the abdomen.

7. Use the sutures to prolapse part of the stomach wall into the two port sites and stitch to the fascia of the abdominal wall.

ACHALASIA OF THE CARDIA

Appraise

1. Achalasia, in which the lower segment of the oesophagus fails to relax ahead of a peristaltic wave, is probably part of a generalized condition of neuromuscular origin associated with abnormal vagal motor input and myenteric ganglionic degeneration. The failure to relax is associated with a failure of peristalsis above.

2. As achalasia advances there is gradual dilatation of the oesophagus, ending below in a smooth, beak-like entrance into the stomach. Retention of contents within the oesophagus produces oesophagitis, and if the retained food is aspirated the patient may develop respiratory disorders, including pulmonary fibrosis. For these reasons do not delay effective treatment.

3. The diagnosis must be confirmed by oesophageal manometry. The aim should be to make the diagnosis at an early stage before the typical X-ray changes appear.

4. Achalasia can be treated using forceful dilatation of the lower oesophagus, or by surgical myotomy of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Injection of botulinum toxin also alleviates the symptoms, but has a relatively transient effect and is not recommended for routine use.

FORCEFUL DILATATION

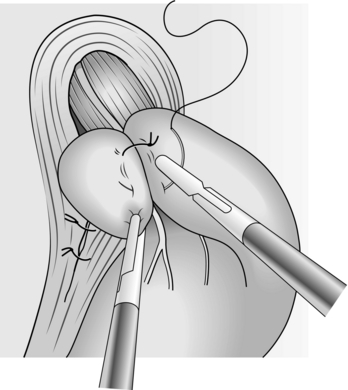

1. This is carried out on the conscious patient under sedation with midazolam.

2. The procedure is undertaken using a plastic dilating balloon, which is specifically made for treating achalasia, is inelastic beyond a predetermined diameter and ruptures when it is overdistended. Increasing sizes of balloon may be used on successive days. The procedure must be performed under fluoroscopic control whether by an endoscopist or interventional radiologist. A radio-opaque, flexible, soft-tipped guidewire is passed through the cardia and the achalasia dilator is threaded over the guidewire until the radio-opaque markers at each end of the balloon lie above and below the cardia. The balloon is inflated under screening control until the waist, which initially appears at the level of the cardia, disappears. It is usual to start with a balloon of 2 cm in diameter and increase at increments of 0.5 cm until blood is seen on the balloon. It is advisable to check that there is no leakage by getting the patient to swallow contrast medium while screening the oesophagus.