CHAPTER 12 Odontogenic Infections

Odontogenic infections are among the most frequently encountered infections afflicting humans, the etiology of which is almost always a carious tooth or a tooth suffering from periodontal disease. The vast majority of these infections are minor and acute, and some even drain through the tooth socket, because they are primarily due to chronic periodontal disease. Consequently, there is considerable interest in periodontitis—a chronic inflammatory disease (and by definition a chronic low-grade infection due to a microbial biofilm) of the tooth-supporting structures—as a potential risk factor in the morbidity and mortality of systemic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and premature birth. Research is ongoing to delve more deeply into these relationships.1 Refer to the Suggested Readings for more information on periodontal disease. Another topic that frequently arises with reference to odontogenic infection is osteomyelitis, which is an inflammation of the cortical and cancellous bone. It can follow odontogenic infection that is not completely resolved and when appropriate attention is not paid to the jawbone itself on follow-up. Again, refer to the Suggested Readings for more information regarding osteomyelitis.

Odontogenic infections, whether acute or chronic, have been plaguing humanity for millennia, and there are many documented stories, engravings, artifacts, and the like to prove this point.2 A great deal of pain and suffering continues to be a scourge, especially in populations that neglect dental care, do not have access to dental care, or ignore professional advice on proper oral hygiene. Extraction of the offending tooth usually results in resolution of the infection, even without antibiotics. However, some of these minor tooth-related infections occasionally become more serious and potentially life threatening, especially in immunocompromised patients. The need for more aggressive surgical and medical care is usually necessary then to prevent more disastrous results.

Microbiology of Odontogenic Infections

Odontogenic infections are usually caused by normal endogenous flora. The mouth contains many microenvironments, allowing for colonization of many bacterial species. Once this environment is established, which varies with factors such as age, immune status, type of diet, and preferred environment, it can and does change over a lifetime. Table 12-1 lists many of the common “normal” aerobic, facultative, and anaerobic species of bacteria (several fungal species, viruses, and even protozoans can also be found in the “normal oral flora”). In most patients, these normal oral bacteria are the cause of most odontogenic infections. Other organisms can be implicated, however, if there is a compromised host or unusual oral environment, such as that found in chronic osteomyelitis. Facultative streptococci are the most numerous group of organisms in the oral cavity and members of the viridans group are the most abundant; these are classically based on their type of hemolysis on agar. Noticeably absent from these normal organisms are the staphylococci, although they are present in nearly every mouth, but in small numbers. Staphylococcus aureus, in particular, is much more common in the nose and throat, and may participate in mixed odontogenic infections. Gram-negative anaerobes comprise much of the rest of the mouth’s normal flora, and these organisms can increase in numbers, especially in patients with chronic periodontal disease.3

| Aerobic Bacteria | Anaerobic Bacteria |

|---|---|

| Gram-positive Cocci | |

| Streptococcus |

Adapted from Peterson LJ. Odontogenic infections. In: Cummings CW, ed. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. Vol 2. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993:1199.

In a recent study describing the microbiology of head and neck infections of odontogenic origin by Rega and colleagues,4 the most common bacteria isolated were viridans streptococci, Prevotella, staphylococci, and Peptostreptococcus. This finding has been consistent for many years, even as name changes (especially for Bacteroides) have taken place to better reflect more recent genetic information.5–9

Based on the results of many studies in the literature and much clinical anecdotal evidence, two important conclusions can be drawn regarding the microbiology of odontogenic infections: First, almost all odontogenic infections are due to mixed flora. Peterson states that the average number of different organisms is five, but can be as great as 10 or more.10 Second, between one third and two thirds of these infections are primarily anaerobic,4,10 which probably has to do with the timing of obtaining the cultures.

Implications of Microbiology for Antibiotic Therapy

Two microbiologic factors must be kept in mind, however, when making this choice: first, the antibiotic must be effective against Streptococcus, because these bacteria are ubiquitous in odontogenic infections; second, the antibiotic should be effective against a wide range of anaerobes, because up to 90% of infections involve some of these bacteria. Fortunately, oral anaerobes are still very susceptible to available antibiotics.11,12

Regarding recommendations for antibiotics, first, it is most useful to use a bactericidal antibiotic rather than a bacteriostatic, if available. The advantages of a bactericidal antibiotic are (1) less reliance on host resistance, (2) killing of the bacteria by the antibiotic itself, (3) faster results, and (4) greater flexibility with dosage intervals.13 Second, use of the most narrow-spectrum antibiotic first should be considered to allow less opportunity for development of resistant strains. Third, the addition of metronidazole to a beta-lactam antibiotic can add a significant benefit in the treatment of odontogenic infections, especially those considered to be mostly anaerobic. As always, the treating clinician must follow the clinical course of the patient and make the appropriate adjustment in antibiotic therapy as circumstances warrant.14–17

Direction of Spread of Infection

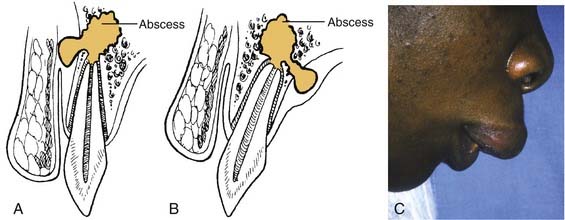

If no treatment is instituted, the infection erodes through the thinnest, nearest cortical plate of bone and into the overlying soft tissues (Fig. 12-1). Fig. 12-1A shows the root apex to be nearest the labial cortex; Fig. 12-1B shows the root apex to be nearest the palatal plate; Fig. 12-1C is a clinical photograph of a patient with a lip swelling, reflecting Fig. 12-1A. Clinical experience reveals that in the maxilla, Fig. 12-1A, is more common in that generally the labial-buccal cortex is thinner. If the root apex is centrally located, the infection erodes through the thinnest bone first, that is, the path of least resistance.

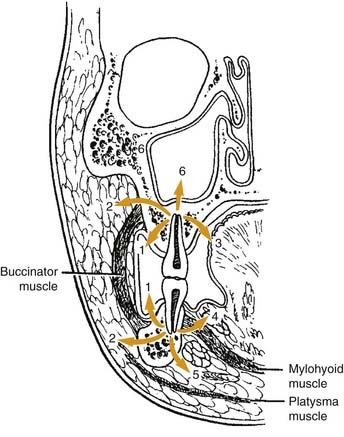

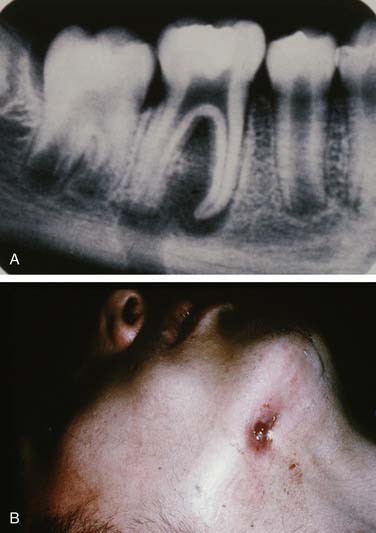

Once the bone has been perforated, local muscle attachments determine the location of the soft tissue abscess (Fig. 12-2). The most common pathway for the abscess is through the labial or buccal bone, occlusal to the muscle attachments, resulting in a vestibular swelling (Fig. 12-3). The vestibular abscess is seen as a fluctuant swelling, literally a “pus pocket,” adjacent to the affected tooth or teeth. If no treatment is provided, this pouch of pus usually ruptures and a sinus tract or fistula is established. At this point, the patient’s pain is relieved and he or she may believe that all is okay, especially because there are few, if any, systemic symptoms. However, if the tooth continues to be neglected, one of several things can happen. Slowly over time the bone involvement with the abscess can increase with more dissolution, possibly involving adjacent teeth. The patient may develop the classic “gum boil” or parulis, which is the body’s attempt at healing the sinus tract with ever-increasing amounts of granulation tissue. Occasionally the tract becomes congested and the pain and swelling may briefly return, until the built-up pressure causes release and relief. This cycle may repeat many times. The one meaningful consequence of continued neglect is development of an osteomyelitis, which may be more severe and more difficult to eradicate. Another unusual possibility is development of an orocutaneous fistula, which is much more common when it occurs in a longstanding mandibular infection (Fig. 12-4).

If the infection perforates the bone above the muscle attachment (see Fig. 12-2, points 2, 4, and 5), fascial space involvement occurs. When this happens, the potential for more severe infection and more significant systemic symptoms becomes greater. A rare occurrence, in my experience, is an odontogenic infection creating a sinusitis, reflected in Fig. 12-2, point 6. The sinus membrane provides a modicum of protection to the spreading infection and allows the body’s defenses to “wall off” the abscess, most commonly.

Fascial Space Involvement

Maxillary Spaces

The canine space becomes infected almost exclusively as a result of apical infection of the root of the maxillary canine tooth. The root must be long enough to ensure that the apex is superior to the insertion of the levator anguli oris muscle. The canine space is located between the anterior surface of the maxilla and the levator labii superioris. When infected, there is usually swelling lateral to the nose and loss of the ipsilateral nasolabial fold. Drainage is most often accomplished with an intraoral stab incision (Fig. 12-5).

Figure 12-5. Patient with a canine space abscess. Note the swelling and obliteration of the nasolabial fold.

(From Goldberg MH, Topazian RG. Odontogenic infections and deep fascial space infections of dental origin, Figure 8-9. In: Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:169.)

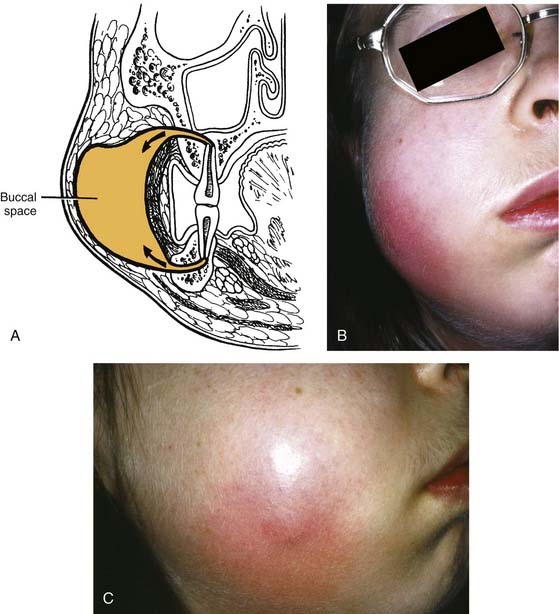

The buccal space becomes involved when the infection of maxillary molar teeth breaks out superior to the attachment of the buccinator muscle. The space itself lies between the buccinator muscle and the skin. All three maxillary molars (uncommon with the third molar) may cause infection in this space; rarely the premolar teeth do. It is an ovoid space, below the zygomatic arch and above the inferior border of the mandible. Infections in this space are dramatic in appearance and may cause trismus, although this is not a consistent finding and may be more of a limitation than actual muscle involvement. The buccal space may also be infected from the mandibular molar teeth, but this involvement is not common. Drainage can be intraoral, but dependent drainage is difficult to obtain. In longer standing buccal space infections, pointing usually occurs and an extraoral incision and drainage is necessary; unfortunately, this usually leaves a noticeable scar after healing (Fig. 12-6).

In addition to these two maxillary space involvements, maxillary odontogenic infections may ascend to cause orbital cellulitis or cavernous sinus thrombosis. These are rare complications in that most patients seek treatment before coming to these extremes. The clinical picture of both of these complications is similar regardless of cause. Early in the course, there is infraorbital edema due to blockage of lymph channels. Progression can then lead to significant swelling and redness of the eyelids, chemosis, and exophthalmos. Once the septum is breached, involvement of the orbital contents includes both vascular and neural components (Fig. 12-7).

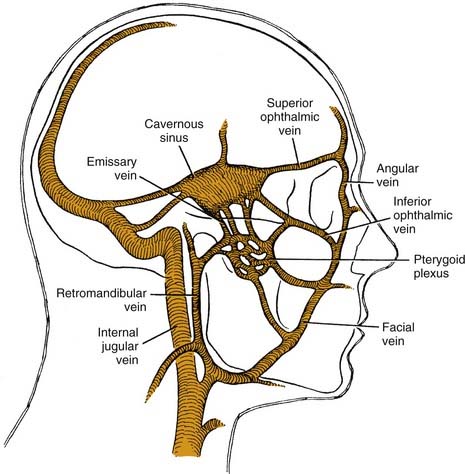

Cavernous sinus thrombosis may also occur as a result of the superior spread of an odontogenic infection.19 Spread to the cavernous sinus is hematogenous and may occur along an anterior or a posterior route (Fig. 12-8), because orbital veins lack valves, permitting blood flow in either direction. This allows contaminated venous drainage into the cavernous sinus. Fortunately this is a rare occurrence and most causes of cavernous sinus thrombosis are nonodontogenic. Signs and symptoms are like those of orbital cellulitis,20 and are related to the structures in the cavernous sinus.

Mandibular Spaces

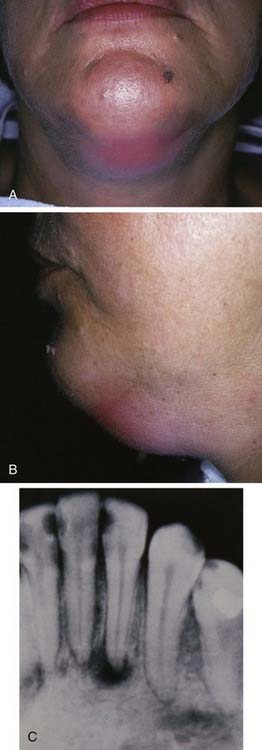

The primary spaces are those into which infection spreads directly from the teeth through bone. The submental space lies between the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles and between the mylohyoid muscle and the skin. This space is involved with infected mandibular incisors, whose roots are long enough to allow erosion apically to the attachment of the mentalis muscle. Isolated submental space infections are not common (Fig. 12-9).

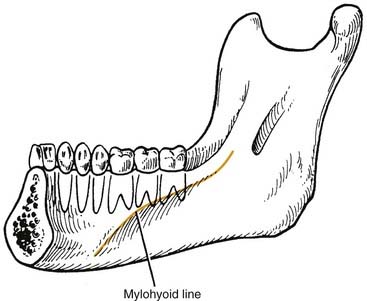

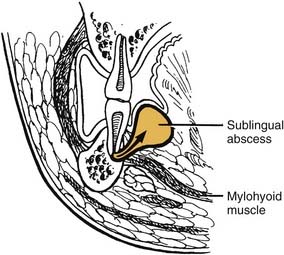

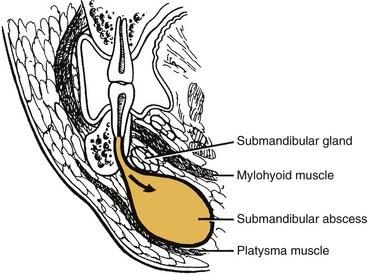

The sublingual and submandibular spaces exit on the medial aspect of the mandible. They are usually involved because of lingual perforation of infection from the mandibular premolars and molars. The factor that determines whether the sublingual or submandibular space is involved is the location of the perforation relative to the mylohyoid muscle attachment (Fig. 12-10). If the location of the apex of the tooth is superior (premolars, first molar), the sublingual space is involved. Conversely, if the apices are inferior to the mylohyoid (second, third molar), the submandibular space is involved. However, the second molar may be sublingual or both, pending its root apex location.

The sublingual space is between the lingual oral mucosa and the mylohyoid muscle (Fig. 12-11). Its posterior boundary is open, so it communicates freely with the submandibular space and the secondary spaces located more posteriorly and superiorly. Clinically, there is little extraoral swelling, but there can be marked intraoral lingual swelling in the floor of the mouth, and if bilateral, the tongue will be elevated and swallowing becomes very difficult.

The submandibular space lies between the mylohyoid muscle and the skin (Fig. 12-12). Like the sublingual space, it has an open posterior boundary, so it can communicate easily with the secondary spaces as well. When this space becomes infected, the swelling begins at the inferior lateral border of the mandible and extends medially to the digastric area and posteriorly to the hyoid bone (Fig. 12-13). Clinically this is a large potential space and the patient is likely to ignore initial swelling; it will not be until the infection has progressed substantially that the patient will seek care.

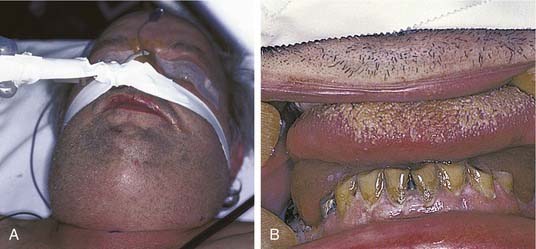

If all three primary spaces bilaterally become infected, the infection is known as Ludwig’s angina. Ludwig’s angina, described by Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig in 1836,2 was not uncommon in the preantibiotic era and was a significant cause of death. It is characterized, even in the antibiotic era, as a rapid, bilateral gangrenous cellulitis of all three primary spaces. It can and usually does extend posteriorly to involve the secondary spaces. It causes gross swelling, elevation and displacement of the tongue, and tense brawny induration of the submandibular region superior to the hyoid bone (Fig. 12-14). There is usually minimal or no fluctuance because of the rapidity of the cellulitic process. The patient experiences severe trismus, drooling, inability to swallow, tachypnea, and dyspnea. Impending compromise of the airway produces marked anxiety. If not treated, the cellulitis can progress with alarming speed, producing upper airway obstruction and, ultimately, death. The usual cause is an odontogenic infection from a mandibular molar. Clearly virulent streptococci are involved, but ultimately, it is a mixed picture as usual.21,22

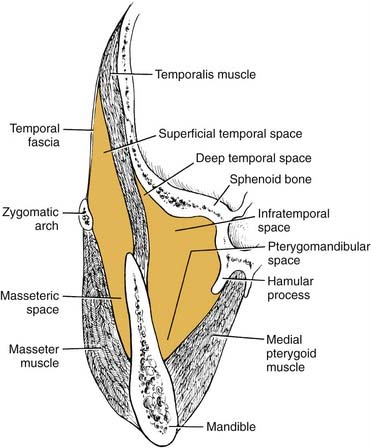

The masseteric space exists between the lateral aspect of the mandible and the masseter muscle (Fig. 12-15). This space is involved from posterior spread of a buccal space infection or from soft tissue infection around the third molar. When involved, the posteroinferior portion of the face swells, especially at the angle of the mandible (Fig. 12-16).

Figure 12-16. Young patient with a masseteric space infection. Note the obliteration of the angle of the mandible.

The pterygomandibular space (medial pterygoid space) lies between the medial aspect of the mandible and the medial pterygoid muscle (see Fig. 12-15). This space becomes involved from spread posteriorly of the sublingual and submandibular spaces and from soft tissue infection around the third molar. When this space is involved, there is little or no swelling extraorally, but there is significant trismus, a clue to the diagnosis.

The temporal space is posterior and superior to the masseteric (lateral) and pterygomandibular (medial) spaces (see Fig. 12-15). Bounded laterally by the temporalis fascia and medially by the skull, it is divided into two portions by the temporalis muscle: superficial and deep. Infection in these spaces is more uncommon, unless the infection is overwhelming. Involvement may occur occasionally with extension of a soft tissue infection around a maxillary third molar, in which case the infratemporal portion of this space may first become infected. This area is just the inferior portion of the temporal space and is contiguous with the deep compartment. Swelling is evident over the temporal area, and if the superficial compartment is singularly involved, the swelling can be dramatic.

Collectively, these three secondary spaces are known as the masticator space, since they are bounded by the muscles of mastication: masseter, medial pterygoid, and temporalis. These spaces communicate freely with one another, so it is most common to find multiple spaces involved in any one infection. Again, the singular diagnostic symptom of masticator space involvement is trismus (Fig. 12-17).

Cervical (Deep Neck) Spaces

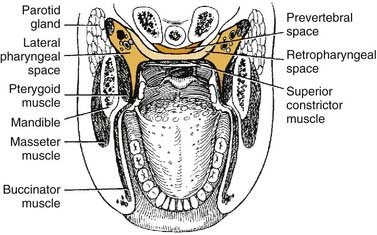

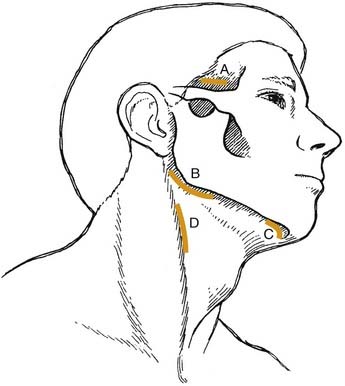

The lateral pharyngeal space is classically described as having the shape of an inverted pyramid. The base is the skull base at the sphenoid bone, and the apex is at the hyoid bone. It is located between the medial pterygoid muscle laterally and the superior pharyngeal constrictor medially (Fig. 12-18). Anteriorly the boundary is the pterygomandibular raphe, around which it communicates with the spaces of the mandible. Posteromedially it extends to and is bounded by the prevertebral fascia and communicates freely with the retropharyngeal space. The styloid process and its attached muscles and fascia divide the lateral pharyngeal space into an anterior compartment, which contains muscles, and a posterior compartment, which contains the carotid sheath and cranial nerves.

When the lateral pharyngeal space is involved in an odontogenic infection, there is trismus, because there is extension from the mandibular secondary spaces. If it is severe, it may interfere with accurate diagnosis and treatment. Lateral neck swelling, especially beyond the angle of the mandible, is usually seen, and intraorally, the lateral pharyngeal wall, when visualized, bulges toward the midline. One can differentiate it from a primary peritonsillar abscess primarily because the latter rarely has significant trismus (Fig. 12-19).

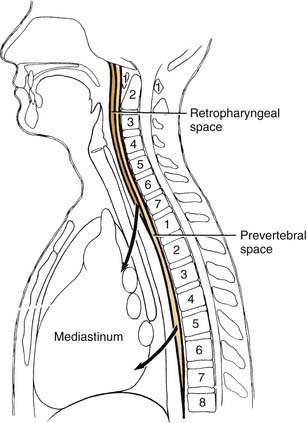

The retropharyngeal space lies posteromedial to the lateral pharyngeal space. It is bounded anteriorly by the superior pharyngeal muscle and its investing fascia and posteriorly by the alar layer of prevertebral fascia (see Fig. 12-18). The space begins at the skull base and extends inferiorly to the level of C7 or T1, where the alar and buccopharyngeal layers of fascia fuse (Fig. 12-20), at the level of the posterosuperior mediastinum.

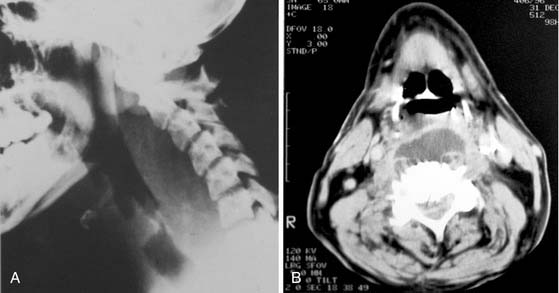

When the infection has extended into the retropharyngeal space, the situation is grave and requires immediate attention. Trismus is severe in essentially all patients at this stage and evaluation of the retropharyngeal space is best performed by evaluation of a lateral radiograph of the neck and a computed tomography (CT) scan, as long as time is not delayed in obtaining one. Average widths of the prevertebral tissues have been well established.23 The soft tissue shadow should be no more than 7 mm (average: 3.5 mm) at C2 and no more than 20 mm (average: 14 mm) at C6, that is, behind the trachea. The CT scan can be very valuable as well (Fig. 12-21).

Involvement of the retropharyngeal space may also include the prevertebral space, which is a potential space between the two layers of prevertebral fascia, the alar and prevertebral layers. It extends from the skull base inferiorly to the diaphragm. The space is also known as the danger space No. 4.24

With infection involvement of these deep neck spaces, the patient is seriously ill and is in grave danger of death. Three great potential complications exist: first, the upper airway is in danger of obstruction due to anterior displacement of the posterior pharyngeal wall into the oropharynx (see Fig. 12-21); second, spontaneous rupture of the abscess can result in aspiration, pneumonia, and asphyxiation or this rupture may be caused by attempts at insertion of an endotracheal tube to secure the airway; third, once the infection has gained access to the retropharyngeal spaces, the mediastinum may become infected also (see Fig. 12-20).

Management of Odontogenic Infections

History and Physical Examination

After a thorough history and physical examination, the clinician should proceed with imaging studies. Experience and the evaluation of the physical examination indicate whether plain films, such as a panoramic radiograph, are sufficient for diagnosis and treatment. In general, CT scans are recommended in addition to plain radiography, if fascial space infections have spread to the orbit or neck.18

Airway Establishment

In patients with Ludwig’s angina, airway embarrassment is the primary cause of death. Once Ludwig’s angina is diagnosed, it is imperative that the patient be monitored frequently and carefully for airway problems. These patients cannot lie flat and have difficulty in swallowing. If the decision is made to establish an artificial airway early, intubation with fiberoptic assistance (or blind nasal technique) can be attempted. These procedures should be carried out on awake, unparalyzed patients. Administration of neuromuscular blocking agents is not warranted because their administration may cause airway loss that cannot be regained. These cases require that an experienced anesthesiologist be present. If the decision to establish an artificial airway is delayed or cannot be accomplished, a tracheostomy or a cricothyroidotomy followed by a tracheostomy is the only option. An unhurried approach with a local anesthetic is preferred.22

Choice of Antibiotic

The drug of choice for odontogenic infections continues to be parenteral penicillin. Even for serious fascial space infections, including Ludwig’s angina,21 penicillin is preferred. Large doses of up to 20 million units daily for intravenous penicillin may be required for serious infections.

Surgical Drainage and Decompression

Jaw Space Infections

The submental space is drained via a horizontal incision, which parallels the inferior border of the symphysis of the mandible (Fig. 12-22). The area between the anterior belly of the digastric muscles is explored posterior to the hyoid bone.

The buccal, submandibular, masseteric, pterygomandibular, and sublingual spaces can all be drained via a horizontal incision parallel and inferior to the angle of the mandible (see Fig. 12-22). An incision from as short as 0.5 cm to as long as 5 cm may be used. If the infection is a tense cellulitis that involves several mandibular spaces, a larger incision is indicated to relieve pressure. After the incision is made, blunt dissection is used to explore the involved spaces. The tip of the hemostat is advanced to hit bone at the inferior border of the mandible. It can then be directed laterally and medially. This medially directed exploration will allow for the medial pterygoid component (pterygomandibular space) to be drained, since it is the most commonly missed space. It can also be directed somewhat anteriorly to drain the submandibular space/sublingual space or a separate incision can be made more anteriorly at the inferior border. The inferior portion to the lateral pharyngeal space just medial to the pterygoid muscle can be explored by this approach as well. In severe infections, anterior (submental), posterior (submandibular), and superior (superficial temporal) incisions may all be required. Penrose drains are inserted to the extent of the dissection to facilitate drainage. Irrigation and suction catheters may be useful in more severe infections,25 because anaerobic bacteria cause significant tissue damage and this debris needs to be flushed out of the wound. In infections drained by multiple incisions, through-and-through drains should be used, because intraoral incisions can also be of value to ensure thorough treatment.

Resolution of these infections depends on several factors: conditions of host defenses, seriousness of the original infection, appropriateness of antibiotic therapy, and extensiveness of surgical exploration. Of these, a failure to perform adequate surgical drainage is most likely to occur, especially if the patient reaches a plateau and does not continue to progress as expected. It may be necessary to repeat CT scans to identify an additional loculation that was not drained at the initial surgery. In the patient with severe cellulitis, overlying induration may prevent the clinical diagnosis of an abscess formation, especially if the patient was taken to the operating room before any scanning. Again additional surgery may be necessary.26

Deep Neck Spaces

Involvement of the deep cervical spaces as a result of odontogenic infection is an uncommon but life-threatening event. A large proportion of these deep neck infections are the result of odontogenic infections that have spread from the primary and secondary spaces of the mandible, because mandibular molars are the likely etiology. When deep cervical involvement does occur, usually beginning in the submandibular space and extending through the pterygomandibular space, the major diagnostic goal is to determine whether the lateral pharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces are involved. The clinical examination, radiography (using anteroposterior [AP], and lateral soft tissue views of the neck; see Fig. 12-21A), and CT (see Fig. 12-21B) may all be required to make the diagnosis. Lateral and AP neck radiographs and CT scans may reveal the presence of gas in the soft tissue as well as soft tissue swelling. The presence of gas in the tissue in this setting signifies an anaerobic infection and indicates immediate and aggressive surgical therapy, because not only does pus need to be drained, but a continuing necrotizing fasciitis is also a concern.

Medical management with antibiotic therapy and host defense support may be used initially without surgery; however, a rapidly progressing infection of the neck should be explored. If gas emphysema, a foul-smelling discharge, or other signs indicating anaerobic infection exist, the indication for surgical intervention increases. If the infection continues to progress rapidly despite aggressive antibiotic therapy, surgical drainage becomes mandatory. If fluctuance is noted, pus should be drained immediately.27–29

Drainage of the lateral pharyngeal space is best accomplished by a combined transoral-extraoral approach. An incision is made lateral to the pterygomandibular raphe, and the space is explored by blunt dissection posterior and inferior to the angle of the mandible with a long Kelly hemostat. A skin incision is made over the clamp tip along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see Fig. 12-22). Loculations of pus are disrupted by blunt dissection with the hemostat and by finger pressure. Through-and-through drains are placed.

Brook I. Treatment of anaerobic infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5(6):991-1006.

Carlson ER, Hudson JW. Odontogenic infections. 4th ed. Cummings CW, et al, editors. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Vol 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby. 2005.

Goldberg MH, Topazian RG, Hupp JR. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections, 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Hudson JW. Osteomyelitis of the jaws: a 50-year perspective. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:1294-1301.

Moutsopoulos NM, Madianos PN. Low-grade inflammation in chronic infectious diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:251-264.

Seymour GJ, Ford PJ, Cullinan MP, et al. Relationship between periodontal infections and systemic disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(Suppl 4):3-10.

1. Moutsopoulos NM, Madianos PN. Low-grade inflammation in chronic infectious diseases, paradigm of periodontal infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1088:251-264.

2. Goldberg MH, Topazian RG. Odontogenic infections and deep fascial space infections of dental origin. In: Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:158-187.

3. Schuster GS. Microbiology of the orofacial region. In: Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:30-42.

4. Rega AJ, Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB, et al. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivities of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1377-1380.

5. Riggio MP, Aga H, Murray CA, et al. Identification of bacteria associated with spreading odontogenic infections by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2007;103(5):610-617.

6. Huang TT, Tseng FY, Yeh TH, et al. Factors affecting the bacteriology of deep neck infections: a retrospective study of 128 patients. Acta Otolaryng. 2006;126(4):396-401.

7. Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, et al. Bacteriology and antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive cocci isolated form pus specimens of orofacial odontogenic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17(2):132-135.

8. Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, et al. Bacteriologic features and antimicrobial susceptibility in isolates from orofacial infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90(5):600-608.

9. Quayle AA, Russell C, Hearn B, et al. Organisms isolated from severe odontogenic soft tissue infections: their sensitivities to cefotetan and seven other antibiotics, and implications for therapy and prophylaxis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:34-44.

10. Peterson LJ. Odontogenic Infections. 2nd ed. Cummings CW, editor. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Vol 2. St. Louis: Mosby. 1998:1354-1371.

11. Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Levi MH, et al. Severe odontogenic infections, part 1: prospective report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1093-1103.

12. Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Hayes C, et al. Severe odontogenic infections, part 2: prospective outcomes study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1104-1113.

13. Peterson LJ. Principles of surgical and antimicrobial infection management. In: Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors. Oral and Maxillofacial Infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:99-111.

14. Blandino G, Milazzo I, Fazio D, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility and beta-lactamase production of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria isolated from pus specimens from orofacial infections. J Chemother. 2007;19(5):495-499.

15. Brook I. Treatment of anaerobic infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5(6):991-1006.

16. Wexter HM. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):593-621.

17. Rush DE, Abdel-Haq N, Zhu JF, et al. Clindamycin versus Unasyn in the treatment of facial cellulitis of odontogenic origin in children. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46(2):154-159.

18. Carlson ER, Hudson JW. Odontogenic infections. 4th ed. Cummings CW, Flint PW, Harker LA, et al, editors. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Vol 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby. 2005:1544-1559.

19. Fielding AF, et al. Cavernous sinus thrombosis: report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;106:342.

20. Karlin RJ, Robinson WA. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:449.

21. Greenberg SL, et al. Surgical management of Ludwig’s angina. Aust N Z J Surg. 2007;77:540-543.

22. Ovassapian A, et al. Airway management in adult patients with deep neck infections: a case series and review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:585-589.

23. Wholey MH, et al. The lateral roentgenogram of the neck. Radiology. 1958;71:350.

24. Grodensky M, Holyoke EA. The fascia and fascial spaces of the head, neck, and adjacent region. Am J Anat. 1938;63:367.

25. Flynn TR, Hoekstra CW, Lawrence FR, et al. The use of drains in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a review and a new approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:508.

26. Lazow SK, Kim D. Imaging head and neck infections. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2001;13:585-602.

27. Beck HJ, Salassa JR, McCaffrey TV, et al. Life-threatening soft tissue infections of the neck. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:354.

28. Dzyak WR, Zide MF. Diagnosis and treatment of lateral pharyngeal space infections. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:243.

29. Haug RH, Picard V, Indresano AT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of retropharyngeal abscess in adults. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;28:34.