CHAPTER 93 Odontogenesis, Odontogenic Cysts, and Odontogenic Tumors

Background

Root Development

The periodontal ligament is actually a joint known as a gomphosis joint. Though the cementum cannot be distinguished except by location, the body, for instance, during orthodontic movement will resorb the bone on the lamina dura side of the periodontal ligament and not the cementum on the tooth side of the ligament. The tooth with the periodontal ligament will retain a certain amount of mobility within the joint. The reader is again referred to various texts for a more in-depth coverage of odontogenesis.1–5,5a

Summary

There are a number of odontogenic epithelial stages and each may provide a basis for odontogenic cysts or tumors. The four main stages considered are (1) dental lamina, (2) enamel organ, (3) reduced enamel epithelium, and (4) Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath. The rests of Serres and Malassez are considered along with their respective progenitors of the dental lamina and Hertwig’s root sheath. In addition, the stomodeal epithelium gives rise to Rathke’s pouch, which retains odontogenic potential. Shafer and colleagues6 suggest the original basal epithelium of the stomodeum also retains potential. In the adult this basal epithelium is represented by the gingival and alveolar mucosal surfaces.6 This concept seems to be supported when peripheral ameloblastomas appear to develop directly from overlying gingival epithelium. With that said, most clinicians would consider the adult basal epithelium to be a rare source of odontogenic neoplasia. The rests of Malassez are common sources of inflammatory odontogenic cysts but retain little neoplastic potential. The rests of Serres, the enamel organ, and reduced enamel epithelium are generally considered the stages most likely to become neoplastic. All stages have the potential to form cysts but to variable degrees. Dentigerous cysts with their origin from the reduced enamel epithelium and radicular cysts from rests of Malassez make up the overwhelming majority of odontogenic cysts.

Odontogenic Cysts

Classification

When reading various sources it becomes quickly clear that what a cyst “is” varies by author and that the classification schemata are in disarray as well. The modified classification scheme seen in Box 93-1 is my attempt at organization. The odontogenic cyst of undetermined origin is a new, admittedly descriptive “diagnosis” used by some oral pathologists. Unfortunately the descriptive nature of that term will not be available to look up in other texts or journals. However, it replaces the diagnosis of primordial cyst. The need to use a descriptive term instead of primordial cyst is due to the ambiguous use of primordial cyst both as an odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) and a simple nonkeratinizing cyst that cannot be classified in relation to the tooth. The descriptive role is to provide a pigeonhole in which to place lesions that are histologically ambiguous, not directly associated with a tooth but located in the alveolus and thus presumably odontogenic in origin.

Box 93-1 Classification of Odontogenic with Other Selected Maxillofacial Cysts

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; WHO, World Health Organization.

Several classification schemata for odontogenic cysts and oral and maxillofacial cysts exist.7–9 The classification scheme seen here is modified from that of the World Health Organization (WHO). In 1992 WHO published the second edition of Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumors.10 Unfortunately the most recent WHO treatise on odontogenic tumors is contained within the Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumors.11 In this change odontogenic cysts are no longer covered within the text. Box 93-1 also contains selected nonodontogenic cysts for completeness and comparison.

By definition a cyst is considered a “pathologic cavity at least partially lined by epithelium.” To be an odontogenic cyst the epithelial lining must be derived from odontogenic epithelium. The best advice to the reader is that all classification schemata are artificial to some extent. The key is to organize them the way that is most useful to you. This modification in Box 93-1 is an attempt at self-clarification and will hopefully be useful for others in either its pure or modified form.

Pathogenesis

Cyst expansion occurs because of numerous factors including accumulation of inflammatory cells, fibrin, serum, and desquamated epithelial cells. As these products enter the cystic cavity, it is the accumulation of the intraluminal products that spurs the cystic expansion of the wall.12–14 Alternatively, cyst expansion may be spurred on by the inherent mitotic activity of the cyst wall itself. If this mitotic activity is the major component of the cyst expansion, it may be better to consider the lesion a cystic neoplasm rather than a simple cyst.14–20 This debate lies at the center of how to classify the OKC, as well as the calcifying odontogenic cyst.21 In the case of the OKC, WHO has renamed it the keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Discussion of this entity is in the odontogenic cyst section. In the case of the calcifying odontogenic cyst (the tumor version), the reader is referred to more detailed articles on the epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor.

Multilocularity may in itself be a signal that the lesional growth is mitotically or multifocally driven rather than hydraulically driven.22–25 For this reason the potentially multilocular odontogenic cysts, such as the botryoid odontogenic and glandular odontogenic cyst, may arguably have a neoplastic potential as well.22,26–30 However, in the case of the botryoid cyst the possibility of multifocality cannot be ignored. Cell regulation protein studies to determine cell inhibition and division activities may be helpful in future classifications.31,32 In addition, the ability of epithelia to break down elements of the connective tissue wall could be important.33–37

However, even simple cysts like the periradicular cyst derived from rests of Malassez must possess some mitotic activation, or growth would be impossible. Activation is thought to occur as a result of inflammatory production within the periodontal membrane.13,38 In the skin and gingiva it has been shown that inflammation leads to release of inhibitors, which then allow the renewal of mitotic activity.15 Once a solid epithelial sphere has been formed, it is thought that it eventually outgrows its vascular nourishment and the central area degenerates to form a lumen.15,16 Following the formation of the central lumen, transepithelial flow of fluid is sustained by osmotic forces. Thus hydrostatic pressure plays a role in the development of the classic unilocular appearance of most cysts. How the pressure results to produce osteoclastic resorption is less clear.17,39–41

Cysts that are derived from the more neoplastic dental lamina, or are in themselves “cystic neoplasms,” probably occur as a result of self-sustained or unregulated mitotic activity.42 Even in neoplastic cysts, luminal expansion may occur through degenerative effects, debris accumulation, and hydraulic and mitotic activity.43–45

Periapical Cyst (Radicular Cyst, Periradicular Cyst)

The periapical cyst must be associated with a nonvital tooth. The tooth may be rendered nonvital by trauma, caries, or periodontal space extension. As such, these cysts may be seen at any age, although permanent teeth are more likely to be involved than deciduous teeth.46 They are thought to be derived from rests of Malassez.

Radiographic Features

Periapical cysts present as a unilocular radiolucency at the apical portion of the tooth. Though well defined, the border varies from corticated to sclerotic to merely well defined. Variations depend on the amount of inflammation present. Long-standing, neglected lesions can get quite large, though most are less than 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 93-1).

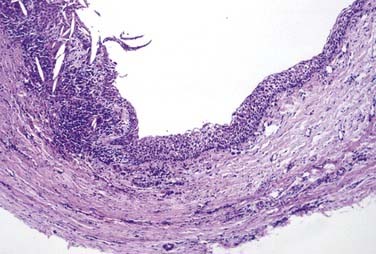

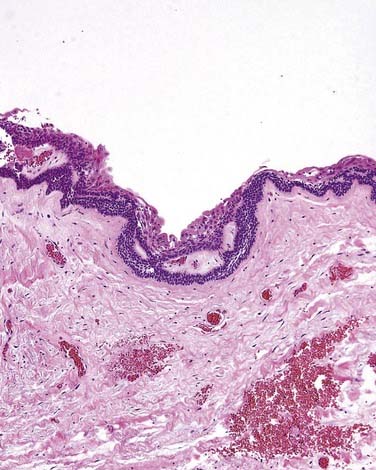

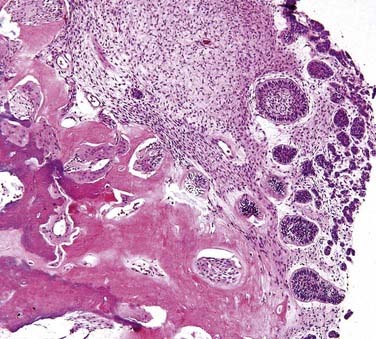

Microscopic Features

This is the classic inflamed “common odontogenic cyst” and as such the luminal lining will consist of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. This is an inflammatory cyst and inflammation is invariably present if sufficient sampling is performed (Fig. 93-2). Rests of Malassez are possible in the connective tissue. However, odontogenic rests are rarely seen in the cyst wall even though these rests are thought to be the source of the epithelial proliferation. Cholesterol slits, foreign body giant cells, and hemosiderin deposits are common findings. As in all “common odontogenic cysts,” squamous odontogenic tumor-like” proliferations may be seen in long-standing lesions. These epithelial islands will be cytopathologically benign without evidence of dysplasia. If squamous odontogenic cystlike proliferations are noted, they should essentially be ignored and are of no prognostic significance. In endodontically treated teeth, foreign bodies secondary to endodontic therapy are common.47 Bacterial colonies may also be seen in these cysts. Though actinomycetes colonies may portend a tendency for being slow to resolve, their presence should not result in a diagnosis of osteomyelitis. Such colonies are more commonly an incidental rather than a significant finding. Thus, for multiple reasons, the proper diagnosis of periapical cyst requires radiographic or clinical corroboration.

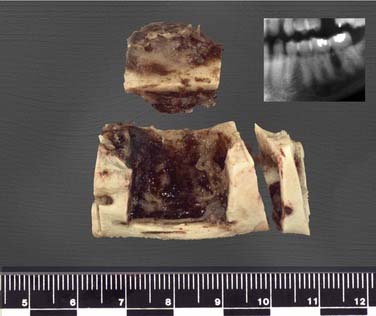

Treatment

This cyst is treated with simple enucleation (Fig. 93-3). Enucleation is often accomplished at the time of tooth extraction. Uncounted numbers of these cysts are probably adequately resolved with endodontic therapy. If a radiolucency persists longer than 6 months following endodontic therapy, enucleation and histopathologic review are necessary.48–50

Residual Cyst

The majority of these cysts will be the result of leaving a periapical cyst “behind” following tooth extraction. All of these cysts are inflammatory cysts. Occasionally an inflamed dentigerous cyst is incompletely removed and could also be the source of a residual cyst. The clinical, microscopic, radiographic, and histologic features are identical to the periapical cyst.48,49,51,52

Inflammatory Collateral Cyst

This may or may not be considered by some to be a true cyst. However, because it is an occasionally used diagnosis, a quick summary is included here. This lesion is associated with periodontal disease of a vital tooth. Uncommonly, a deep intrabony periodontal pocket may be sufficiently isolated to allow for hydraulic expansion of the bone (Fig. 93-4). As such, radiographically there will be a radiolucent periradicular lesion (Fig. 93-5). There will also be a periodontal pocket associated with that radiolucency. This diagnosis should be limited to those cases where the clinician indicates the diagnosis as the most likely choice. Otherwise, the clinical, microscopic, radiographic, and histologic features are identical to the periapical cyst.53

Dentigerous Cyst (Follicular Cyst)

The dentigerous cyst by definition must be associated with the crown of an unerupted tooth, developing tooth, or odontoma. The eruption cyst is essentially a subtype of dentigerous cyst that is confined just by the overlying alveolar mucosa. Dentigerous cysts form when fluid accumulates between reduced enamel epithelium and tooth crown.14 As alluded to earlier, the accumulation of fluid may be partially or largely surrounded by connective tissue and epithelium.54,55 Because the third molars and maxillary canines are the teeth most frequently impacted, they are also the most likely to be associated with dentigerous cysts. However, any impacted tooth has an increased risk. There also may be inherent differences in impacted tooth development and how the reduced enamel epithelium is transformed/resorbed.56 They are generally found in the teenage years and early adulthood.57 However, the longer a tooth is impacted, the greater the chance a dentigerous cyst will develop.58

Radiographic Features

A dentigerous cyst presents as a unilocular radiolucency, which is associated with an unerupted tooth (Fig. 93-6). Dentigerous cysts may also involve odontomas that, by nature, also have “tooth crowns.” The radiolucency is generally well demarcated and well corticated. The border may become sclerotic or display rarifying osteitis if secondary infection is present. Even large cysts that have pushed the associated tooth considerable distances will display evidence of origin from the cementoenamel junction if the film angle is adequate. In large lesions the origin from the cementoenamel junction is best visualized as an area of cortication at the cementoenamel junction. There is considerable overlap between the appearance of small dentigerous cysts and hyperplastic follicles.56

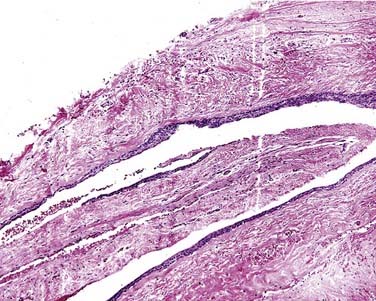

Microscopic Features

The specimen will present primarily as variably dense fibrocollagenous connective tissue with some areas being loose and myxomatous. Odontogenic epithelial rests are usually scattered within the connective tissue and are most common near the epithelial lining. The luminal lining consists of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The presence of mucous prosoplasia within the lumen is not uncommon. Care should be taken to not overinterpret the mucus prosoplasia. Cholesterol slits and their associated multinucleated giant cells may be present in inflamed cysts and are generally associated with the connective tissue wall.47 As mentioned earlier, the lumen may be partially or mostly lined by connective tissue.14 If present in the specimen, crevicular epithelium may make microscopic separation of an inflamed dentigerous cyst from pericoronitis impossible. Thus proper diagnosis requires radiographic or clinical corroboration.

Neoplastic Potential

Dentigerous cysts appear to retain the ability to transform into true neoplasms. One study reported that 17% of ameloblastomas were associated with an existing dentigerous cyst.59 This figure varies by study, however.60–62 Both squamous cell carcinomas and mucoepidermoid carcinomas have been reported.63–67

Eruption Cyst

The eruption cyst is a form of dentigerous cyst that is found in the soft tissue overlying an erupting tooth. Because by definition it must be associated with an erupting tooth, eruption cysts occur only during the ages of tooth development.7 They may be seen with erupting deciduous or permanent teeth, but the majority of lesions are seen in the first decade.68 The lesion will present as a soft tissue swelling of the alveolar ridge overlying an area of age-appropriate tooth development. Some eruption cysts will have a slightly blue hue color, though the normal coral pink color of the surrounding mucosa is common (Fig. 93-8). Unlike dentigerous cysts, it is not uncommon for an eruption cyst to be associated with deciduous teeth. Eruption cysts may be seen in newborns with an incidence of 2 per 1000 births reported.69 Clinical follow-up may also serve to confirm the diagnosis because the tooth will erupt within several weeks to months through the cystic expansion.70–74

Paradental Cyst

The paradental cyst is considered by some to be a variant of the dentigerous cyst. This is because the various forms of paradental cyst all originate from the cementoenamel junction just like the dentigerous cyst. However, the paradental cysts are almost uniformly inflamed, so they are generally classified as inflammatory cysts rather than as developmental cysts. Paradental cysts occur on the buccal or distal aspect of an erupted mandibular molar. Though the mesial aspect of a mandibular tooth may rarely be involved, there have been no reported occurrences to the lingual. Craig75 reported the occasional presence of developmental enamel projections near the furcation of some teeth. This is particularly true of the subcomponent of paradental cysts known as infected buccal bifurcation cysts. How big a role these projections play in pathogenesis remains debatable.76–81 In one series the paradental cyst accounted for 3% of all odontogenic cysts.82

Odontogenic Cyst of Undetermined Origin

The problem in diagnosis comes when a cyst is not associated with the crown of a tooth, residually or with the root of a nonvital tooth. Additionally, the cyst is not consistent with a fissural cyst but is at least partially located in the alveolar process. Historically, any cyst that occurred in an area where a tooth should have developed, or where supernumerary teeth could occur, were originally called primordial cysts.83 This term was used to allude to development from the tooth primordium. Unfortunately, this was proposed in 1945 before delineation of the features defining the OKC and a large percentage of these “primordial” cysts had features of what would now be diagnosed as an OKC. When the OKC was defined in the 1950s, some pathologists had already recognized those histologic features in what they termed primordial cysts and thus they began to use the term interchangeably with OKCs. International journals, especially, came to use the term primordial cyst as a synonym of the OKC.45,84 Americans often avoided the term primordial or left the moniker of primordial cyst for those lesions without features of a keratocyst.

Definition of the Odontogenic Cyst of Undetermined Origin

An odontogenic cyst of undetermined origin is a unilocular radiolucent cyst of the jaws with histologic features of common odontogenic cysts but lacking the clinical, histologic, and radiographic features of any defined common odontogenic cyst (Fig. 93-9).

Lateral Periodontal Cyst

These cysts are thought to be derived from the dental lamina and are thus thought to retain some limited neoplastic growth potential. This limited neoplastic potential is best displayed by the associated lesion known as a botryoid odontogenic cyst. Lateral periodontal cysts are located on the lateral surface of a vital tooth.85,86 This assumes that the tooth has not been rendered nonvital by dental caries or trauma unrelated to cyst formation. The most common location is the mandibular premolar/canine area. If present in the maxilla, the lateral incisor area is the most common location. However, the lateral periodontal cyst may be seen in any area of the alveolar processes. This cyst is seen in the interproximal area between tooth roots and is usually an incidental radiographic finding.87,88 Demographically the cyst is most common in males by a 2 : 1 ratio with a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades.89 The gingival cyst of the adult and the botryoid odontogenic cysts are essentially subtypes of lateral periodontal cysts. Other cysts, especially the OKC, odontogenic cyst of undetermined origin, and the lateralized periapical cyst, also present interproximally. Histopathologic features and tooth vitality are important diagnostic considerations to separate these lesions. All of these lesions can be separated histologically and the lateralized periradicular cyst will be associated with a nonvital tooth.

Radiographic Features

The lesion presents as a unilocular radiolucency of the alveolus that is usually well corticated. Larger lesions may result in diverged roots.90 Multilocular lesions are a special subset and are classified as botryoid odontogenic cysts (see “Botryoid Odontogenic Cyst” later).27

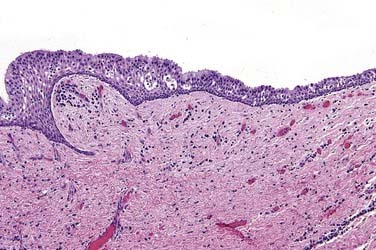

Microscopic Features

The cyst lining is composed of nonkeratinized simple to stratified squamous epithelium. The lining is most notable for being only a few cells in thickness (Fig. 93-10). Intermixed within this otherwise thin epithelial lining are nodular epithelial thickenings or plaques. The plaques may display somewhat whorled epithelial cell aggregates. The central cells in the aggregate may display cytoplasmic clearing. The clear cells contain glycogen, which can be digested with diastase. Scattered mucous cells may be seen in some lesions but should not be a dominant feature.90,91 The diagnosis of lateral periodontal cyst must be reserved for lesions displaying the thin epithelium described earlier. The plaquelike thickenings are helpful microscopic features but are not always found. The connective tissue wall may contain dental lamina rests, but they are not required for diagnosis.

Botryoid Odontogenic Cyst

The botryoid odontogenic cyst will usually present as a multilocular lesion and is a special variant of the lateral periodontal cyst. Botryoid refers to the fact that these lesions may appear like grapelike clusters, both histologically and usually radiographically as well.23,25,27

Radiographic Features

Radiographically the botryoid odontogenic cyst presents in the same preferred alveolar process locations as the lateral periodontal cyst. Small locules may not be seen on radiographs.23

Gingival Cyst of the Adult

Clinical Features

This lesion is essentially the soft tissue equivalent of the lateral periodontal cyst. As with the lateral periodontal cyst, it derives from dental lamina or rests of Serres.92–94 These lesions generally present as an asymptomatic bluish nodule on the facial aspect of the gingiva. The sessile elevation will be centered in the attached gingiva, though extension below the mucogingival line is possible. Unlike the lateral periodontal cyst, there may be a slightly increased incidence in women.95 The mandibular gingiva is most commonly involved and the peak incidence occurs in the fifth and sixth decades.9,96 Other odontogenic cysts may also occur in the gingiva. Histologically distinctive odontogenic cysts that are appropriately diagnosed histopathologically should not be descriptively called gingival cysts. The possibility of some cysts of the gingivae arising from traumatically implanted surface epithelium does exist. Whether it is best to call these histologically different cysts epithelial inclusion cysts is debatable.95 The term gingival cyst of the adult must be reserved for those lesions with histologically distinct microscopic criteria.

Gingival Cyst of the Newborn (Dental Lamina Cyst, Alveolar Cyst of the Newborn)

These cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of newborns. They are generally only a few millimeters in diameter and seen only in the first few months of life. Though studies are appropriately devoid of histologic sampling data, some clinical reports estimate these cysts occur in up to 50% of all newborns. The cysts are sessile and vary from normal in color to yellow or white. Similar-appearing inclusion cysts of the palatal midline (Epstein’s pearls) or at the junction of the hard and soft palates (Bohn’s nodules) are differentiated by location. The gingival cyst of the newborn is a soft tissue cyst and does not have an intrabony component (Fig. 93-11).97

Keratinizing Odontogenic Cyst (Orthokeratinizing Odontogenic Cyst, Orthokeratinizing Odontogenic Keratocyst)

Recognition of the keratinizing odontogenic cyst is a rather recent phenomenon. When the OKC was first defined, the definition did not separate these lesions. Over time several reviewers noted and separated keratinizing cysts that did not seem to otherwise conform with the microscopic criteria of the OKC.98–100 The most notable difference in these cysts was the presence of orthokeratin rather than parakeratin, though other features such as lack of tombstoning, corrugation, and hyperchromatism are more important criteria. Wright101 was the first to formally separate this group of cysts and proposed the name of OKC, orthokeratinizing variant. He noted the different histopathologic features and ably reported the lack of recurrences associated with these orthokeratinized cysts. However, the nomenclature of including the term keratocyst has created quite a bit of confusion, at least anecdotally. Historically, older texts and articles described keratinization of various odontogenic cysts and recognized the difference of these cysts from OKCs.47,100

The designation as orthokeratinized OKC (OKC, orthokeratinized variant) has evolved since first being described. Current nomenclature has evolved to avoid confusion with the “standard” OKC. It is also worth noting that some OKCs can contain orthokeratin, and the original series of “orthokeratinizing OKCs” described by Wright included 7 of 60 cysts with parakeratin.101 Thus classification based solely on the type of keratin alone is unwise.

The separation of the keratinizing odontogenic cyst is clinically important because the reported recurrence rate of the keratinizing odontogenic cyst is only 2%. The peak incidence of keratinizing odontogenic cysts is in the third, fourth, and fifth decades, with about three fourths of them being in a dentigerous cyst relationship. Other locations are possible, in various relationships to the teeth. Most cysts are asymptomatic, though pain and swelling was reported respectively in 22% and 13% of cases.98,99 The keratinizing odontogenic cyst is not associated with basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin-Goltz syndrome).

Radiographic Features

The cyst presents as a well-defined unilocular radiolucency with the border generally being well corticated. If it is in a dentigerous cyst position, a cyst may be large (Fig. 93-12).

Microscopic Features

The epithelial lining will most often be thin with keratinization. However, the thickness will be somewhat variable. Keratin production varies and may only occur on a portion of the cyst wall. Orthokeratin is characteristic but not pathognomonic.102 Most notable are the features that are not present. The features defining an OKC are absent.

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst (Sialo-odontogenic Cyst)

Clinical Features

Controversy encompasses this lesion and undoubtedly further delineation of features will evolve. The glandular odontogenic cyst is usually asymptomatic and involves the mandible more often than the maxilla.29,103 Large cysts may be destructive and expansile.104,105 The glandular odontogenic cyst involves adults and its pathogenesis is not yet understood.106 This cyst may be either multilocular or unilocular. The cyst is generally well defined and often well corticated.

Radiographic Features

The lesion is radiolucent and may be unilocular, but it is more commonly multilocular. The radiographic margins are well defined and usually display a sclerotic rim.107

Microscopic Features

This cyst is lined by cuboidal epithelium of varying thickness, which may display cilia. Unfortunately, separating this particular microscopic feature from “normal” (and insignificant) mucus prosoplasia is sometimes difficult. The following features are more important in establishing the diagnosis. The cyst lining will be mucicarmine positive. The mucin detected by mucicarmine collects in small pools. Characteristically there are cuboidal cells near the surface, which give a slightly papillary appearance to the lumen.103 The epithelium will also contain spheroid aggregates of cells.108,109 The presence of mucous cells in other odontogenic cysts is not diagnostic for this lesion. This lesion, in this author’s opinion, is “overcalled” and second opinion is often necessary. Standard “common odontogenic cysts” with mucus prosoplasia are often “upgraded” to glandular odontogenic cysts (Fig. 93-13). Glandular odontogenic cysts may be “upgraded” to central mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Great care to properly designate these lesions is necessary to ensure proper patient care.

Treatment

Recurrence after enucleation has been reported.103 As in any multilocular lesion, nucleation and curettage of bone is recommended. Few cases are available to draw further treatment conclusions, but the overall prognosis is good.30 Suggestions to treat this cyst aggressively appear to be misguided.

Odontogenic Keratocyst (Parakeratinizing Odontogenic Keratocyst, Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor)

The OKC remains an enigma for the clinician and researcher, although knowledge gains in recent years have allowed for an improved understanding of this interesting lesion. The lesion was first described by Philipsen in 1956, but even 5 decades later the debate continues over the pathogenesis, behavior, treatment, and classification of this cystic neoplasm.18–20 One major dilemma is whether to classify it as a cyst or a neoplasm. The current World Health Organization (WHO) nomenclature stresses the neoplastic nature and uses the term keratocystic odontogenic tumor.

Soft tissue extension, extension into adjacent bones, and expansion with associated bony destruction have been reported. These reports have prompted clinicians to question what the most appropriate method of treatment really is. Scharfferter and colleagues110 documented increased mitotic activity within the epithelial lining of the OKC, which seems to support its neoplastic nature.

Of particular interest to the clinician is the biologic behavior of the OKC. Recurrence rates of up to 62.5% have been reported with enucleation alone. However, modern reports have a much lower recurrence rate when enucleation and careful curettage are performed. Most modern recurrence rates are less than 10%.111,112 Reasons to explain the recurrence rate include daughter or satellite cyst formation113; incomplete removal of the epithelial lining, leaving satellite cysts left behind; collagenase activity of the cyst114; dental lamina rests left in the cyst wall or overlying mucosa; prostaglandin-induced bone resorption115; and increased mitotic activity. A handful of articles have demonstrated that the OKC can proliferate within muscle, and death from intracranial extension of mandibular OKCs has been reported by Jackson and colleagues.84,116,117 Though these case reports should be remembered, the need to aggressively treat all OKCs should be resisted.

Radiographic Features

OKCs may be unilocular or multilocular, multiple, or single. OKCs with calcifications within a cyst wall have been reported, but calcification is rare and OKCs are considered radiolucent lesions. OKCs are highly variable in size (Fig. 93-14). They can appear pericoronally, periradicularly, interradicularly, apically, and even peripherally. In summary, OKCs may occur in all areas of odontogenesis and they may extend significant distances.97 The borders are well defined and often corticated.98,118 Patients involved with Gorlin syndrome are more likely to present with metachronous or synchronous cysts. CT scans may be helpful in assessing large lesions and CTs are often essential in assessing maxillary lesions.119–121

Treatment

A handful of reports with significant complications have led some clinicians to perform aggressive surgical procedures on all lesions. Debate persists about how to best manage OKC lesions in general. Treatment should center on decreasing the recurrence rate to a rate expected of the modern era and one that reduces patient morbidity. The reader is referred to other articles. After reading many treatises, the following is my opinion.111,112,122–130

If the patient has more than one cyst, the possibility of basal cell nevus syndrome is elevated. All cysts should still be examined histopathologically to confirm diagnosis. Clinical work-up to assess for syndrome is always prudent when multiple concurrent or sequential OKCs are diagnosed. Even when OKCs are in teenagers or younger patients are diagnosed with a single lesion, at least a cursory family history and gross clinical assessment for the syndrome should be performed. Some investigators have claimed good success with decompression and subsequent enucleation, while others advocate enucleation, excision of overlying mucosa, peripheral osteotomy, and chemical curettage.125,129

The use of Carnoy’s solution is controversial. Carnoy first reported use of his fixative for the study of nematodes in 1887.131 His goal was to fix the tissue and preserve nuclear detail for microscopic examination. However, fixation of the tissue intraoperatively for future microscopic exam is not really the effect that surgeons desire. Surgeons desire the chemical cauterization effect that the solution produces.

Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome (Gorlin Syndrome, Gorlin-Goltz Syndrome, Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome)

This complex syndrome is called by many names, and the nomenclature often depends on what portions of the syndrome (e.g., bifid ribs, OKC) are present. In the Gorlin and colleagues132–134 description, no fewer than 37 anomalies have been associated with this syndrome. The reader is referred to the original sources.

OKCs are often the first diagnosis of the syndrome to present in childhood and often aid in establishing a diagnosis. This is especially true in cases in which there are new mutations with no prior familial history.135 Up to 40% of cases may be new mutations, though genetic testing is advancing and there may be large variations in expression in this autosomal dominant disease.134 One patient’s first cyst occurred in the seventh decade. For this reason the syndrome should not be ruled out even in a middle-aged patient, and family history and phenotype may help in all age groups.

Treatment

The key to management of these patients is to at least phenotypically evaluate any patient that has an OKC for the syndrome. The assessment may be as simple as screening the patient for clinical evidence of any anomalies. In syndromic patients, “recurrences” should be presumed new occurrences rather than recurrences. Decompression is highly desirable in large lesions, and teeth should generally be saved rather than extracted if possible. Undoubtedly some teeth will need to be removed for access, but canines, incisors, and first molars should be heavily favored for retention. Each case is highly variable. As a medical advisor for this syndrome’s support group I invite all providers to contact www.bccns.org for information.

Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst (Gorlin Cyst)

The calcifying odontogenic cyst (COC) is an unusual odontogenic lesion. As with the OKC, experts debate whether to classify the COC as a cyst or neoplasm. In this chapter the primarily cystic lesion with ghost cells is considered first, and the more solid epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor is considered later. The cyst was described by Gorlin and colleagues136,137 in 1962. It is worthy of delineation because of its unusual clinical and histopathologic features. The COC occurs both within the bone and peripherally in the gingiva. COCs are often associated with odontomas or active products of odontogenesis.138

The separation of the cystic lesions from the solid lesions is appropriate. The solid/neoplastic version is considered briefly in the odontogenic tumor section under epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor.139 The occurrence of the COC compared with the epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor may approach 40 : 1. Subclassification of the cysts is more of a histologic exercise than of prognostic or therapeutic importance. The reader is directed to articles by Praetorius and colleagues and Hong and colleagues for subclassification schemata.140,141

The origin of the COC is probably the early dental lamina. This may be best supported by the fact that craniopharyngiomas of the pituitary region often mimic the COC. COCs occur over a large age range. Though the mean age at occurrence is in the fourth decade, the peak incidence is in the second and third decades. Lesions in young adults are often associated with odontomas. The anterior portion of the jaws is more commonly involved than posterior regions, though any area can be involved. There is essentially equal distribution between females and males when all types are considered. There may be a slight maxillary predominance over the mandible.139 Peripheral COCs will be centered in the attached gingiva.

Radiographic Features

The radiographic appearance is highly variable. As with the OKC, it may be either unilocular or multilocular, though unilocular lesions are more common. This is one of the odontogenic lesions that is classically considered to be mixed radiolucent radiopaque, though most lesions are purely radiolucent in the absence of an associated odontoma. If mineralization occurs in COCs without an odontoma, the radiopacities are often peripherally located. This appearance has been compared to “snowdrifting.”142

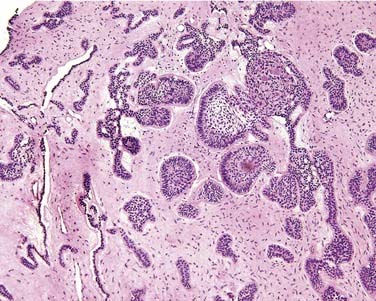

Microscopic Features

Ghost cells are the classic cells seen in the COC. Ghost cells are not pathognomonic of COCs. In fact, ghost cells may be seen with other lesions such as odontomas, ameloblastic fibro-odontomas, and ameloblastomas. Of more significance is the presence of odontogenic epithelium with hyperchromic nuclei and somewhat of a palisaded basilar layer (Fig. 93-15). The thickness of the cyst wall is fairly thin and generally less than 10 cells thick. However, the thickness varies along the luminal wall and plexiform connections are often present, which creates a multicystic appearance in more complicated cysts.

Treatment

Treatment of the COC is simple enucleation of unilocular lesions. As in any multilocular lesion, enucleation with bony curettage is adequate therapy for the central lesions. The peripheral lesions require simple excision.143 Recurrence is not expected, though radiographic follow-up is prudent.

Malignant Odontogenic Tumors and Malignancies Arising in Odontogenic Cysts or Tumors

Malignant transformation of odontogenic cysts is fortunately a rare occurrence but nonetheless occurs.144–146 Many malignant transformations are considered to arise from residual cysts and occur in an edentulous area.147,148 Transformation from an associated dentigerous cyst is seen in 25% of the reported cases.146 Some OKCs have shown dysplastic features with few actually undergoing malignant transformation.149,150 In summary, any cyst can undergo malignant transformation but such lesions are rare. Malignant lesions are likely to present with pain and swelling, but dysthesia is a foreboding symptom. Gardner reviewed the literature from 1889 to 1967 and found 25 acceptable examples of carcinoma arising from an odontogenic cyst.151 A MEDLINE search for this chapter yields more than 100 additional examples.

Central mucoepidermoid carcinomas are thought to arise directly from prosoplastic cells of odontogenic cyst linings.67,152–154 However, almost all types of salivary gland malignancy have been reported centrally in the jaw and the possibility of entrapped salivary tissue cannot be totally excluded. Bruner and Batsakis153,155–157 reviewed a total of 66 reported cases of central mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the jaws, which indicates they may be more commonly reported than central squamous cell carcinoma malignancies.

Elzay156 offered a classification for primary intraosseous carcinomas of the jaw in 1982. A scheme of classification is offered in Box 93-2 with modifications from that of Elzay to allow for salivary malignancies (especially mucoepidermoid carcinomas), origin from odontogenic tumors (other than ameloblastoma), and inclusion of sarcomas.

Box 93-2 Classification of Malignant Odontogenic Tumors with Other Selected Malignancies

Verifying carcinomas arising de novo is difficult, but de novo cancers may be assumed if confined to intra-alveolar bone without a soft tissue component. Cysts appear to be a more common site of origin than odontogenic tumors. But nearly all odontogenic tumors have been reported to have malignant counterparts. The age at occurrence is in the sixth or seventh decade with some reports of a 2 : 1 male predominance, but full-ranging reviews are lacking.157 And even if such reviews were available for all lesions seen in Box 93-2, their wildly variable characters would most likely be as appropriate as comparing apples with oranges.

Odontogenic Tumors

The odontogenic tumors are a heterogeneous group of tumors that are generally separated in classification schemes by what components of odontogenesis are present within the tumor. Box 93-3 shows the classifications used in this chapter. When reviewing the treatment of these tumors, multiple considerations must be accounted for. When many articles are reviewed it becomes clear that there is a great desire for a “cookie cutter” type of recipe approach for every lesion based on diagnosis alone. Unfortunately, this just is not a realistic approach and in this author’s opinion has resulted in gross overtreatment in a number of patients. As with the odontogenic cysts, the presence of scalloping and particularly multilocularity makes curettage following enucleation necessary. Although scalloping and multilocularity may be seen on planar films, intraoperatively the surgeon is in an ideal position to assess for these features in three dimensions. If scalloping or multiple locules are noted intraoperatively, curettage is appropriate at the time of biopsy to avoid having to reoperate.

Box 93-3 Classification of Odontogenic Tumors

In the mandible more emphasis needs to be paid to inferior and posterior cortical bone relationships to the tumor to potentially avoid discontinuity resections of these benign lesions. With the exception of ameloblastoma, there are only a handful of reports of mandibular benign odontogenic tumors “getting away” from the surgeon into soft tissues or nearby bones. Yet a cookie cutter approach is often applied. Ameloblastoma-like therapeutic models are applied to many benign odontogenic tumors. I am not aware of any studies on the morbidities associated with nonameloblastoma recurrences in the modern world of imaging. Likewise, despite studies associated with the jaw resections and obturators (generally in cancer therapy),159–168 there are no studies on quality-of-life issues associated with benign odontogenic tumor therapy. Evidence to support recommended treatment margins is usually based on comparing recurrence rate with ameloblastomas, not the biologic behavior of the tumor. In addition, the 1-, 1.5-, and 2-cm margins recommended are often unclear. Regarding benign odontogenic lesions other than ameloblastomas, studies that have actually controlled for confirmed resection margins, pathologically and radiographically before and after surgery, are terribly lacking. For ameloblastomas Carlson and Marx169 do a credible job in advocating resection. They also account for frozen sections, biologic barriers, and utilization of intraoperative radiographs (Fig. 93-16). However, they fail to recognize the simple fact that the actual goals are to ensure and confirm tumor removal, not to have a one-size-fits-all guideline. They also discuss confusion about solid and nonunicystic cystic ameloblastomas. More discussion of this problem is provided later. Gardner does an excellent job on the problems of doing retrospective analysis of the literature on ameloblastomas.170

In the maxilla, 1-cm bony margins are sometimes recommended in the proximal-distal direction. However, the anatomy of the sinuses, nasal cavity, orbit ethmoids, and pterygoid plates in many instances makes the use of anatomic boundaries more appropriate. In general, one or two anatomic boundaries are sufficient to ensure excision. In all lesions, even the ameloblastoma, the periosteum is thought to be an effective tumor barrier.171 The interested lifetime/evidence-based learner is invited to perform a MEDLINE search of actual invasive benign odontogenic tumors. A 4-decade review by Leibovitch and colleagues172 found only 11 reported cases of ameloblastomas with orbital involvement. A MEDLINE search for this chapter revealed about the same amount of reports (using search terms of ameloblastoma combined sequentially with “invasi,” “extension,” and “involve”) revealed, in a cursory review of abstracts, approximately 25 to 40 cases/reports with the majority being from an original maxillary lesion. Without a doubt, soft tissue extension of recurrent ameloblastomas is a real problem, with Sampson and Pogrel documenting a high percentage of ameloblastomas involving soft tissues in a series of 26 cases.173 But the ameloblastoma is a special case and is covered more thoroughly later. The following section discusses general principles concerning the other odontogenic tumors. With the exception of malignant variants, the reports of other odontogenic tumors extending, involving, or invading other adjacent structures are extremely rare.

The maxillary lesions are more problematic due to the short distance needed to involve areas difficult to operate in and oblate the tumor. Such areas include but are not limited to the pterygoid plates, orbital floor, and pterygopalatine fissure. The head and neck surgeon realizes that in some areas any benign tumor is difficult to access and completely remove. Thus persistence of tumors in these areas is more a problem of location than of the inherent invasive potential of the tumor. Carlson and Marx169 do a good job of discussing biologic barriers in their article.

Unicystic Ameloblastoma

Unicystic ameloblastomas account for approximately 15% of all ameloblastomas. Unicystic ameloblastomas may be found in any odontogenic tissue–bearing area. Most unicystic ameloblastomas are found in the posterior mandible. Unicystic ameloblastomas most often occur in the second and third decades, a somewhat younger population than reported for the solid ameloblastoma. As with other odontogenic cysts and tumors, unicystic ameloblastomas are usually asymptomatic unless secondarily inflamed.97

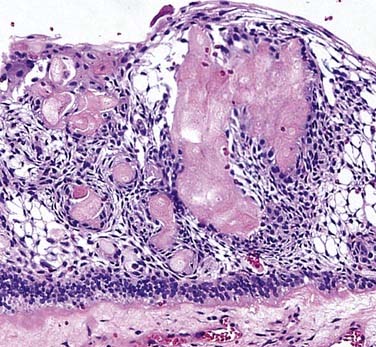

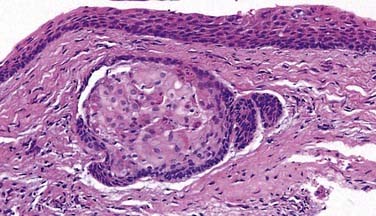

Microscopic Features

The microscopic features known as Vickers and Gorlin criteria define the unicystic ameloblastoma. These features are (1) columnar basilar cells, (2) palisading of basilar cells, (3) polarization of basilar layer nuclei away from the basement membrane, (4) hyperchromatism of basal cell nuclei in the epithelial lining, and (5) subnuclear vacuolization of the cytoplasm of the basal cells. Above the basal layer, loosely aggregated stellate cells resembling the stratum spinosum of a developing tooth are noted (Fig. 93-17).174 It is important to realize that some portions of unicystic ameloblastomas may not show all these features. A variation of unicystic ameloblastoma described by Gardner allows for a plexiform variant. Inflammation may disrupt the diagnostic features of unicystic ameloblastoma.175–177

Definitions, Clarifications, and Treatment Recommendations

A unicystic ameloblastoma must be unilocular, as well as unicystic, and display the pathologic features of an ameloblastoma lining the lumen but not invade the connective tissue (Fig. 93-18). From the beginning, criteria have varied and caused confusion, but this definition applies in the following discussion.

The unicystic ameloblastoma was separated from the “standard” ameloblastoma by Robinson and Martinez in 1977.178 The subtitle of that seminal paper was “a prognostically distinct entity.” Since that time the application of their original definition has been problematic, with others often further muddying the picture. A number of authors have attempted to provide evidence of predicted behavior for different types of unicystic ameloblastomas.178–183

The first premise in this chapter’s coverage of the unicystic ameloblastoma is that the only reason to separate the unicystic ameloblastoma is for therapeutic planning and expected clinical behavior. Ever since the original paper, it has been regrettable that multilocularity and connective tissue invasion were sometimes allowed within the diagnostic criteria. Ackermann and colleagues183 have analyzed unicystic ameloblastomas with connective tissue invasion as “type 3.” They found that they often recur if only enucleation is performed as therapy. For this reason, though, they should be more thoroughly studied and managed like a standard ameloblastoma. And thus separation as a “unicystic” ameloblastoma is spurious at best. Likewise, Philipsen and Reichart182 found that multicystic or multilocular cystic ameloblastomas recurred with simple enucleation. Again, this should make it clear that they should not be grouped under the designation of unicystic ameloblastoma. These features are seen in “regular” ameloblastomas, and determining where to draw the line of what is too much multilocularity or too much connective tissue proliferations is totally subjective and unwise unless future studies define a method to separate lesions. Until such studies, unicystic ameloblastomas should be considered as such only if they are unicystic and unilocular and display no connective tissue invasion.

Some additional background information may also be helpful. Eversole and colleagues184 found recurrences more common (actually all four recurrences) in lesions larger than 2 cm. Unfortunately they did not stratify their data to state whether these larger lesions were multilocular or how the connective tissue wall was invaded.184 But this report implies that large or expansile lesions may recur even if the ameloblastoma is cystic. Likewise, a review of the original paper by Vickers and Gorlin,174 which defined the features of ameloblastomas, reveals that all their cases were recurrences of what today would have been diagnosed as unicystic ameloblastomas.

Unicystic does not mean unilocular. Some authors allow for a multilocular radiographic appearance.185 These authors often use terms such as cystic or cystogenic instead of unicystic. Regardless, the intent is to attempt to group these lesions with the unicystic ameloblastoma. Some purport that histologically the multilocular lesion was unicystic (how they confirm three dimensionally how a single cyst can make multiple locules and remain unicystic has never been adequately explained in my opinion). However, in my review of the literature, multilocularity increases the chance of recurrence and multilocular lesions should be at least enucleated and curetted rather than just enucleated. In my institution, multilocular and multicystic lesions would be signed out simply as ameloblastoma and presumed to be treated as such. Unilocular lesions may be histologically multicystic. Multicystic lesions are not unicystic lesions, so they should be considered standard ameloblastomas and treated as such.

In their review of 193 “unicystic” ameloblastomas, Philipsen and Reichert182 found wide variations in definitions, nomenclature, and what lesions were included under the heading “unicystic” ameloblastoma. Simply put, the literature is horrible. Even separation of terms such as luminal, intraluminal, and mural varies among authors.

As proposed originally by Robinson and Martinez,178 the reason for the diagnosis of “unicystic ameloblastoma” was to separate “a prognostically distinct entity.” Even in their report, Robinson and Martinez had a recurrence rate of about 20%. But they allowed for connective tissue nests, multilocularity, and large cysts. Two of their three lesions described as “large dentigerous cysts” recurred. Eversole and colleagues184 later used 2 cm as a cutoff for size because they found that larger “cystogenic” ameloblastomas had a propensity to recur with simple enucleation. Robinson and Martinez178 did not separate lesions by connective tissue involvement. But authors including Philipsen, Reichart, and Ackerman and colleagues (in various publications) have shown that connective tissue involvement is an important predictor of recurrence with simple enucleation. They designate these as what they call type 3 unicystic ameloblastomas and state that they tend to recur (i.e., behave like “standard” ameloblastomas if only enucleation is performed). Current wisdom is that the 20% recurrence rate of Robinson and Martinez may have been due to large size or connective tissue proliferations.

Simple Unicystic Ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma, Intraosseous Type*

Definition

Intraosseous ameloblastomas occur in the mandible and maxilla with the mandible accounting for about 80% of all cases. In the maxillae, ameloblastomas may evolve in the maxillary sinonasal region, as well as during the alveolar process. The location of the tumor is an important factor in the long-term prognosis. Tumors that are in the anterior maxilla or body of the mandible or are confined to the mandible are less likely to cause significant problems. Conversely, those penetrating the mandible in the posterior ramus region and those of the posterior maxilla can extend into areas difficult to manage.186

Radiographic Findings

Small ameloblastomas appear as a unilocular radiolucency with well-demarcated and at least partially corticated borders. These radiolucent lesions are indistinguishable from other cysts or benign tumors of the jaws (Fig. 93-19). Larger lesions may be easier to recognize radiographically. The classic description of larger lesions is a “soap bubble” or honeycomb appearance. Roots of adjacent teeth may show resorption in long-standing lesions. An ameloblastoma commonly displaces unerupted or erupted teeth. These radiographic features describe all histologic variants except for some desmoplastic ameloblastomas. In desmoplastic ameloblastomas of sufficient duration, a mixed radiolucent radiopaque lesion rather than a pure radiolucency may be seen. Additionally, the desmoplastic ameloblastoma is more common in the maxilla and anterior portion of the jaws.97

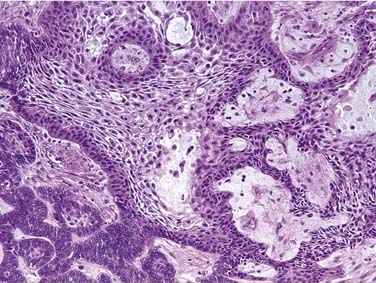

Microscopic Features

Multiple microscopic subtypes of ameloblastoma exist. Although they are of importance to the pathologist, these histologic subtypes are not of therapeutic or prognostic importance. But in summary, histologic subtypes include follicular, plexiform, granular cell, acanthomatous, desmoplastic, basal cell, and keratinizing. The classic features of ameloblastoma were described by Vickers and Gorlin.174 These features are columnar basilar cells, palisading of basilar cells, polarization of basilar layer nuclei away from the basement membrane, hyperchromatism of basal cell nuclei in the epithelial lining, and subnuclear vacuolization of the cytoplasm of the basal cells. Above the basal layer, loosely aggregated stellate cells resemble the stratum spinosum of a developing tooth (Fig. 93-20).

Natural History and Treatment

Gardner pointed out two main factors that explain the behavior of ameloblastomas: (1) their ability to infiltrate medullary bone and a relative inability to infiltrate compact bone; (2) the location of the tumor. As noted earlier, tumors near vital structures such as the orbit or cranial base are much more difficult to control and pose greater clinical problems. Free margins of excision are difficult to obtain in ameloblastomas arising in the posterior maxilla. Dense compact bone such as that of the inferior border of the mandible or ramus acts as the first-line barrier.187 The outer periosteum appears to serve as a backup barrier to prevent tumor spread, but once it is broken, access to vital structures may occur.171 In the maxilla, only a thin cortical plate exists between contiguous bones and is generally thought of as a poor barrier to prevent the spread of ameloblastomas.169 Tumors of the posterior maxilla involving the orbit are the most difficult to treat and manage. Undoubtedly such lesions will present with unique and specific problems related to the individual case.188

Simple enucleation of ameloblastomas is not considered standard care in the United States. Even when it is combined with curettage, ameloblastomas are known to recur. Yet successful results with enucleation and curettage have been reported.189,190 The recurrence rate is thought to be due to the fact that ameloblastoma infiltrates the trabeculae of cancellous bone. The reported success with curettage (or peripheral ostectomy with rotary bur) is probably due to relatively efficient/aggressive medullary bone removal. It is generally considered a fact that tumor infiltration frequently extends beyond the apparent radiographic margin. Ensuring even amounts of bone removal with enucleation and curettage can be difficult. Small bits of tumor may remain within the bone without the ability to assess margins grossly or histologically. It is thought that resection with adequate margin is the most predictable method to assure that the tumor will not recur. A resected specimen allows for intraoperative radiographic assessment of adequate margins and postoperative histologic confirmation of margins.

What an adequate radiographic margin should be is more controversial and probably varies by case. Even after en bloc resections, reportedly well past radiographic evidence of tumor, recurrence rates of 10% to 15% have been reported. Although some surgeons advocate larger margins, the general consensus is that resection should be 1 cm past the radiographic limits of the tumor. Unfortunately, there are no well-controlled studies of radiographs of the resected specimen compared with postsurgical defects to actually confirm what margins were achieved. Likewise, although there are anecdotal reports, there are no controlled studies of resected specimens correlated with radiographs to assess how far the tumor actually extended histologically past that radiographic evidence. Carlson and Marx have made initial attempts to accumulate such data, but a well-documented study has not yet been performed.169 Due to the lack of reliable data, the following discussion is yet another anecdotal opinion on how to manage ameloblastomas.

Management of Maxillary Ameloblastomas

Assessing bone margins in maxillary bone resection specimens is even more important. Some authors recommend 1- to 2-cm margins in the maxillae. The larger end of the range is probably unnecessary in the anterior region and difficult to obtain when lesions approach the orbit or pterygoids, or both. Again, such margin recommendations pertain to attempted bony margins and not to soft tissues. Soft tissue margins must be assessed by frozen section or on properly oriented permanent sections. Treatment of maxillary lesions varies greatly and depends on both CT and MRI interpretation. Follow-up of maxillary lesions is extremely important and it is assumed that attempts to spare vision and vital structures of the region may alter initial treatment plans. Excision to extend two biologic barriers past the tumor serves as a rule of thumb. The en bloc specimen should be examined intraoperatively from multiple radiographic views. Final margin assessment occurs after demineralization. Though not often recommended, radiotherapy may occasionally play a role in unresectable tumors.191 Similar to the mandibular tumors, the periosteum above the level of muscle attachment is the surgical margin. Overlying mucoperiosteum, teeth, gingiva, and mucosa are submitted with the resected specimen.

Peripheral Ameloblastoma (Extraosseous Ameloblastoma)

Peripheral ameloblastomas present as mucosal masses and arise from the gingiva or alveolar mucosa. The actual proliferation may come from dental lamina rests or basal cells of the overlying mucosa. Histopathologically the lesions appear as any of the previously mentioned variants, though the basal cell variant is the classic subtype. By definition these tumors do not infiltrate the underlying bone. If there is an intraosseous component, the lesion is not a peripheral ameloblastoma. If there is bone involvement, the lesion is treated as an intraosseous ameloblastoma. Peripheral ameloblastoma may become quite large. Lesions may be imaged with MRI or CT. Treatment is to assure excision with histopathologically confirmed margins.209–218

Malignant Ameloblastoma

Malignant ameloblastomas are lesions that have any of the classic benign histopathologic features of ameloblastoma but metastasize to a distant location. In many cases the metastases are long delayed and may occur years after the initial tumor was treated. The lung is the most common site for metastases. Cervical lymph node involvement has also been reported. Treatment varies by degree and site of involvement. Though excision is preferred, radiotherapy may be the only practical option.219–224

Ameloblastic Carcinoma

Ameloblastic carcinoma, in contrast to malignant ameloblastoma, shows cytopathologic features associated with malignancy (e.g., increased mitotic activity, increased nuclear and cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromatism). The cytopathologic/histopathologic features allow for this being diagnosed in the primary location. The tumor may or may not metastasize, but like the primary tumor the cytopathologic features display the anaplastic features of malignancy. These are rare lesions.225–234

Ameloblastic Fibroma

The ameloblastic fibroma is a benign odontogenic neoplasm characterized by proliferation of immature mesenchymal and ameloblastic cells, both of which are characteristic of a developing tooth. Unlike the ameloblastic fibro-odontoma or the odontoma (complex and compound), the ameloblastic fibroma does not have the capacity of producing enamel, dentin, or cementum. The tumor can be found in any tooth-bearing site. However, the tumor is most often seen in the premolar-molar region of the posterior mandible. There is no gender predilection, but the lesion is usually identified in a bimodal age distribution. The majority of lesions are diagnosed before age 20, though another smaller group of lesions is seen in middle age. As with other odontogenic neoplasms, the lesion is slow growing and asymptomatic unless secondarily inflamed. A firm expansion of the buccal cortical plate of the mandible or maxilla is the most common clinical finding. The lesions are most often small and unilocular. It is thought that an early version of odontoma necessarily goes through a stage that is histopathologically indistinguishable from an ameloblastic fibroma. Separating these early odontomas from a “real” ameloblastic fibroma is impossible. However, there are reports of large and destructive ameloblastic fibromas that clearly require the ameloblastic fibroma to be classified as a neoplasm rather than a hamartoma. The tumors that become large and destructive are perhaps more likely to be seen in older patients.235–239

Microscopic Findings

The histopathologic features of an ameloblastic fibroma are characterized by the proliferation of both epithelial and mesenchymal elements. The mesenchymal component presents as a relatively cellular-young, basophilic, fibromyxoid tissue suggestive of a developing tooth pulp or dental papillae. The fibroblastic cells vary from stellate to spindled. Admixed within the mesenchymal background are islands, cords, or nests of odontogenic epithelium. The outer epithelial cells near the basement membrane become cuboidal and occasionally columnar, at least focally. These islands are essentially identical to islands seen in follicular ameloblastomas. By definition, ameloblastic fibromas will have no areas of mineralization. If mineralization is seen, the lesion is actually an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma (Fig. 93-21).97

Treatment

Conservative surgical enucleation of the tumor is the treatment of choice for all small, unilocular lesions. The tumor does not have the infiltrative margins characteristic of an ameloblastoma and therefore recurrence rates are low. With early detection and removal, the long-term prognosis is favorable. However, larger multilocular lesions may be destructive and reports of recurrence up to 40% were reported in a 1972 article from a series of cases at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.239 Segmental resection is not indicated in any tumor except those that have essentially already destroyed the integrity of the jaw involved.

Ameloblastic Fibro-odontoma

The ameloblastic fibro-odontoma is a rare odontogenic tumor. The lesion has had some controversy in the literature in regard to its appropriate classification. Similar to the ameloblastic fibroma, it is thought that a maturing odontoma necessarily goes through a stage that is histopathologically indistinguishable from an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma. However, reports of large and destructive ameloblastic fibro-odontomas clearly confirm its ability to act as a neoplasm rather than a hamartoma. The majority of patients with ameloblastic fibro-odontoma are young, with a mean age of 10 years. Whether these data are skewed from improper inclusion of maturing odontomas is difficult to assess. Undiscovered tumors can cause significant cortical plate expansion. Most are discovered during other radiographic studies or when a tooth has failed to erupt. Occasionally the tumor can persist or recur. It is probably most prudent to assess the individual tumor and patient in its context. If the tumor is large and destructive, it is more likely to be acting neoplastically. Multilocular tumors should be assumed to be neoplastic.97,240,241

Radiographic Findings

The tumor is a well-circumscribed, unilocular or multilocular lesion.242 Though evidence of mineralization must be present histopathologically to make the diagnosis, the mineralizations will not always be evident radiographically. Therefore early lesions may be radiolucent. The amount of mineralization varies widely.

Microscopic Findings

The histopathologic features of an ameloblastic fibro-odontoma are characterized by the proliferation of both epithelial and mesenchymal elements. The mesenchymal component presents as a relatively cellular-young, basophilic, fibromyxoid tissue suggestive of a developing tooth pulp or dental papillae. Admixed in the fibromyxoid tissue are mineralized and premineralized elements including enamel, enamel matrix, dentinoid, dentin, cementoid, and cementum. Admixed within the mesenchymal background are islands, cords, or nests of odontogenic epithelium. These scattered epithelial components are identical to those seen in the ameloblastic fibroma (Fig. 93-22).243–246

Treatment

Small ameloblastic fibro-odontomas are generally treated with simple enucleation. Multilocular lesions should be additionally treated with curettage/peripheral ostectomy with a rotary instrument. Unerupted teeth associated with the tumor may be retained. Depending on the amount of displacement and root development, they may or may not need orthodontic intervention to ensure eruption. Very large, inherently destructive lesions require complete but conservative surgical removal. Recurrences have been reported but are extremely rare. Segmental resection is not indicated in any tumors except those that have essentially already destroyed the integrity of the jaw involved.247,248

Epithelial Odontogenic Ghost Cell Tumor (Dentinogenic Ghost Cell Tumor, Odontogenic Ghost Cell Tumor)

In conjunction with this brief section, please refer to the earlier discussion on the calcifying odontogenic cyst. The epithelial odontogenic ghost cell tumor is an unusual jaw lesion that consists of a complex (at least focally), solid, tumor-like mass, though a cystic area is usually present as well. As with other odontogenic neoplasms and cysts, the lesion can occur in any tooth-bearing site. Most reports indicate that the lesion occurs most often in the posterior mandible. Most lesions arise centrally within bone; however, lesions may be identified as arising peripherally within the gingiva. Extensive data on these tumors is scarce but is assumed to have a similar age distribution as the calcifying odontogenic cyst. Terms such as malignant and aggressive have been appended to this diagnosis. Personally the malignant appendage should only be used in cases where cytomorphologic characteristics of malignancy are noted. “Aggressive” lesions are identified by inherent destructive behavior or recurrence. Central bony lesions usually present as a firm, expansile mass of the buccal cortical plate. The lesions are asymptomatic unless secondarily inflamed. Gingival lesions appear as a firm, smooth, sessile, soft tissue enlargement involving the attached gingiva or edentulous alveolar ridge. These peripheral masses may present on either the buccal or lingual aspect.139,140,249–261

Review of the International Collaborative Study on Ghost Cell Tumours is a must-read when one of these lesions is encountered.139 A pathologist well versed with all forms of this tumor should be consulted for proper classification.

Calcifying Epithelial Odontogenic Tumor (Pindborg Tumor)

The calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor is an unusual odontogenic neoplasm characterized by sheets of hyperchromatic, pleomorphic cells with foci of amyloid and mineralization. Calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumors occur more often in the mandible than the maxilla with a ratio of about 2 : 1. Within the arch, they are often located in the molar-premolar region. As with other odontogenic tumors, they may or may not be associated with unerupted tooth crowns. Those seen in the second decade are often associated with an unerupted tooth. The tumors are rare but have been reported more often in males. The tumor most often occurs in the third through fifth decades.97 This tumor is rarely seen peripherally as a gingival mass or alveolar ridge mass.262,263

Radiographic Findings

The tumor is usually well circumscribed with a multilocular appearance being more common than a unilocular lesion. Though evidence of mineralization is often present histopathologically, radiographically the mineralizations will sometimes not be evident. However, this is one of the classic mixed radiolucent-radiopaque lesions of the jaws. The amount of mineralization varies widely with some lesions having minimal evidence of radiopacity (Fig. 93-23). The peripheral lesions may produce a cupping effect of the underlying bone. In these instances the cupping is thought to be secondary to pressure resorption.

Microscopic Findings

The tumor is characterized by islands and sheets of epithelial cells dispersed throughout a nonspecific fibrous stroma. In many instances the polygonal, epithelial cells show remarkable pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromasia. Borders of the epithelial cells are well defined and prominent intracellular bridges are characteristic. The cytoplasm is often strikingly eosinophilic, but tumors may display a prominent clear cell component.264,265 Foci of homogeneous eosinophilic amyloid may be present.

Odontogenic Myxoma

The odontogenic myxoma is a relatively uncommon, benign neoplasm apparently arising from the mesenchymal portion of the tooth-forming unit known as the dental papillae/dental sac. Odontogenic myxomas have been identified most often in the posterior tooth-bearing areas of the dental arches and present in both upper and lower jaws. The mandible is more commonly involved than the maxilla. Most tumors are identified during the second or third decades of life. No gender predilection has been identified. As with other odontogenic neoplasms, clinical findings usually consist of a smooth, bony, hard expansion of the alveolus. The primary process of the odontogenic myxoma is to infiltrate through medullary spaces. Intraoperatively the myxoma is seen as gelatinous material (Fig. 93-24). Judging where the gelatinous material ends intraoperatively and especially radiographically may be difficult. In some instances odontogenic myxomas do penetrate the cortex. They have also been reported as forming outside the body of the mandible, in which case they would present as a smooth-surfaced gingival enlargement.97,267–271

Radiographic Findings

As with many other odontogenic neoplasms, an odontogenic myxoma may present as either a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency. Most lesions show radiolucency with variable cortication. When the cortical bone is penetrated, a periosteal reaction may result in apparent osseous production. Residual or reactive bone may also be seen intraosseously272 and give a somewhat mixed radiopaque/radiolucent appearance. Cone beam CT may be helpful.273 When residual bone is somewhat organized, the appearance has been described as similar to either a honeycomb or tennis strings.274

Treatment and Prognosis

Due to the loose, gelatinous nature of the tumor, surgical enucleation can be difficult to judge. However, the odontogenic myxoma is another lesion where the tumor has not been reported to “get away” from the surgeon on recurrence. The goal of treatment should center on removal of medullary bone well past the radiographic borders. Recommendations of how much medullary bone to remove vary,271,275 but 0.5 to 1 cm of medullary bone removal appears to be prudent. Removal of cortical bone in areas of penetration is also recommended. Recurrence rates can vary significantly from case to case and often show a direct correlation with the size of the lesion at initial diagnosis. Large and clinically aggressive tumors may necessitate segmental resection. In such cases the surgery is derived not from the diagnosis but by the nature of the lesion at hand. Intraoperative radiographs as described in treatment of ameloblastomas are also appropriate. Confirmation of margins histopathologically is also essential before reconstruction. Grossly the gelatinous material may also be easily seen at resected margins intraoperatively (Fig. 93-25).

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor

The adenomatoid odontogenic tumor is a relatively infrequent odontogenic tumor that has vague histologic similarities to ameloblastoma. Unfortunately the histologic similarity led to past nomenclature as adenoameloblastoma or ameloblastic adenomatoid tumor. The vague microscopic similarity is this tumor’s only similarity with that more aggressive tumor. Clinically the adenomatoid odontogenic tumor is by far the most innocuous odontogenic tumor, at least if the odontoma is considered a hamartoma. It appears that the tumor derives from the enamel organ epithelium but may arise from dental lamina rests. Though the actual ratio varies slightly by report, the adenomatoid odontogenic tumor is often known as the two-thirds tumor because it occurs two thirds of the time in females and two thirds of the time in the maxilla. Two thirds of the time this tumor is associated with impacted teeth (especially the canine), and two thirds of these tumors are found in teenagers. It is unusual in patients older than 30 years of age. Occasionally an adenomatoid odontogenic tumor arises peripherally within the gingiva. It is most often discovered radiographically when exploring the reason that a canine has not erupted long after its contralateral partner.97,276–279

Microscopic Features

The tumor consists predominantly of spindle-shaped epithelial cells that form whorled masses or rosettes in a scant fibrous stroma. Ductlike structures lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells are the classic histopathologic feature. Foci of amyloid, if present, are usually seen in the rosette/adenomatoid arrears. Other mineralized material may also be seen. These mineralizations are usually not well organized but may resemble dentin, cementum, or aborted attempts at enamel production.280–282 Cystic spaces are also common. Some may be true luminal surfaces, though the largest surface lumen is probably adjacent to the tooth crown.

Treatment

These lesions are very well encapsulated and therefore easily enucleated. Aggressive behavior is never anticipated and recurrence is not a problem, though large lesions have been reported.276 The lesion can be enucleated and the tooth can be left in place for eventual eruption or orthodontic therapy.

Odontomas

Odontomas are the most commonly diagnosed odontogenic tumors. They are considered by many to be a hamartoma rather than a true neoplasm. Odontomas are subdivided into two subtypes: complex and compound odontomas. Complex odontomas, when fully developed, consist almost entirely of intermingled aggregates of enamel, enamel matrix, dentin, and cementum arranged in a haphazard manner. Compound odontomas consist of enamel matrix, dentin, and cementum. Unlike the complex odontoma, the mineralized elements are organized with the overall appearance suggestive of multiple small, malformed, but easily identifiable teeth. These toothlike elements can easily be seen at the grossing table. Some epithelial elements may be seen peripherally. These epithelial cells represent the reduced enamel epithelium from which the hard tissues were formed. Odontogenic rests are also seen peripherally. Just as with an unerupted tooth, these epithelial linings and rests may lead to formation of dentigerous cysts. Likewise, any odontogenic cyst or tumor may also develop in association with an odontoma. Complex and compound odontomas occur with equal frequency and some lesions show features of both subtypes. Depending on size and location, they may deform adjacent teeth or delay eruption.97,283,284

Squamous Odontogenic Tumor

This tumor is mentioned briefly because it is extremely rare with fewer than 100 ever reported. The lesions are generally small and usually present as “inverted” periodontal bone loss. Gingival tumors have also been described.285,286 That is, in periodontal disease the triangular base is toward the cementoenamel juntion. In the squamous odontogenic tumor the base is toward the tooth apex. Familial and multifocal cases have been reported. Any portion of the tooth-bearing area may be involved, and the paucity of cases does not allow for much demographic analysis. The importance of the tumor is that the squamous epithelial islands seen microscopically may be misinterpreted. The squamous islands are cytopathologically totally benign. Yet their presence deep in connective tissue may be misinterpreted as invasion. The invasive appearance may lead to misdiagnosis as either an acanthomatous ameloblastoma or, worse, a squamous cell carcinoma. Tumors are easily treated with enucleation and simple conservative curettage.286–289 Squamous, odontogenic, tumor-like proliferations are well known as being occasionally associated with inflammatory odontogenic cysts. These proliferations are inconsequential and do not warrant additional treatment or diagnostic proclamation.290–292

Odontoameloblastoma

Controversy surrounds the definition of odontoameloblastoma, and several lesions have likely been described under this designation. One subset of lesions given the moniker of odontoameloblastoma most likely represents an ameloblastoma arising from the epithelial elements of an odontoma. Other reports describe aggressive, large tumors that would be difficult to separate histologically from an “aggressive” ameloblastic fibro-odontoma.293–295 One report of dentinoid production with an ameloblastoma could be an additional subset.296 LaBriola and colleagues297 also reviewed the difficulties associated with this diagnosis and reported one case, as did other researchers.298,299 Generally these tumors define themselves by their destructive and/or recurrent behavior. Because of difficulties in histologic criteria, the diagnosis should always be made in consultation with a pathologist well versed in head and neck/oral pathology.

Ackermann GL, Altini M, Shear M. The unicystic ameloblastoma: a clinicopathological study of 57 cases. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:541-546.

Baden E. Odontogenic tumors. Pathol Annu. 1971;6:475-568.

Brannon RB. The odontogenic keratocyst. A clinicopathologic study of 312 cases. Part ii. Histologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43(2):233-255.