Oculodermal Surface Disease

A variety of disorders affect both the skin and the ocular surface. This chapter will focus on the oculodermal disorders that primarily affect the ocular surface, their clinical findings and principles of management. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid will be covered in greater detail in Chapters 30 and 31, respectively.

Rosacea

Acne rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the central facial skin and may involve the eyes in up to 58% of patients.1,2 Albeit common, rosacea is often overlooked, even though ocular rosacea is classified as one of the defined clinical subtypes of the disease. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial in order to avoid disfiguring facial involvement, ocular morbidity and the emotional distress that untreated disease may cause.3

Epidemiology

Rosacea affects 16 million Americans and is commonly recognized to be more prevalent in fair-skinned patients of Celtic or Scandinavian origin.4 Women are more commonly affected than men, and the onset is typically between the ages of 30 and 50 years.4

Etiology

The precise etiology of rosacea is uncertain. Among the various theories of causation are inflammatory, infectious, dietary, and psychological theories. Several studies support an inflammatory mechanism. An elevated concentration of interleukin-1 and greater activity of gelatinase B (MMP-9) were found in the tear fluids of patients with ocular rosacea.5 Vascular dilation and incompetence may also contribute to the signs and symptoms of the disease.6 Microbial organisms such as Helicobacter pylori and Demodex folliculorum have been identified as possible causative factors of the disease.6 Molecular studies suggest that an altered innate immune response may be involved in the pathogenesis of this disorder, inducing high levels of cathelicidin, an antimicrobial peptide with vasoactive and pro-inflammatory actions.7

Diagnosis

There is no objective diagnostic test specific to rosacea. The diagnosis is clinical, and the disease is often underdiagnosed since patients may be unaware of their symptoms, and physicians may not recognize the early findings, especially early ocular disease.3

A standard classification proposed by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee was published in 2002. This classification system describes primary and secondary features of rosacea and defines four subtypes of the disease (erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular). Evolution from one subtype to another may or may not occur. The features of rosacea are listed in Table 22.1.4

Table 22.1

Primary and Secondary Features of Rosacea

| Primary Features | Description |

| Flushing (transient erythema) | Frequent blushing or flushing |

| Non-transient erythema | Persistent redness of the facial skin |

| Papules and pustules | Red papules with or without pustules. Nodules. |

| Telangiectasia | Telangiectases are common but not necessary for a rosacea diagnosis |

| Secondary Features | Description |

| Burning or stinging sensations | |

| Elevated plaques | |

| Dry appearance | Dry appearance of central facial skin |

| Edema | Facial edema |

| Ocular manifestations | |

| Peripheral location | |

| Phymatous changes |

The presence of one or more of the primary signs with an axial facial distribution is indicative of rosacea. One or more of the secondary features may or may not be present.4

(Adapted from the Standard Classification of Rosacea, proposed by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee (Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M et al. Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:584–7)

Clinical Findings

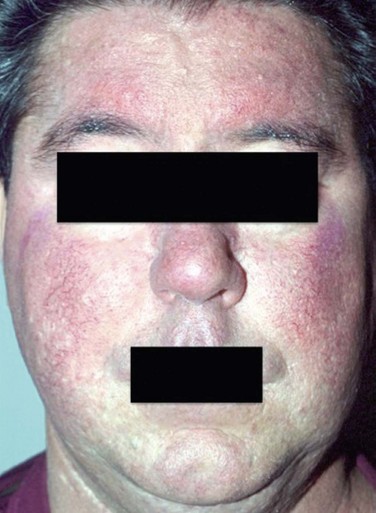

Rosacea develops gradually and begins with transient flushing that may be triggered by certain factors that are specific to each individual. The most common triggers are listed in Table 22.2. As disease progresses, transitory erythema and telangiectasia of the skin become apparent. Chronic, untreated disease may present with persistent erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules and sebaceous gland hypertrophy localized primarily on the convexities of the central face (cheeks, chin, nose and forehead) (Fig. 22.1).4

Table 22.2

Most Common Trigger Factors of Rosacea

| Foods and Drinks | Environmental | Emotional |

| Spicy food | Sun exposure | Anger |

| Chocolate | Heat | Stress |

| Soy sauce | Excessive cold | Embarrassment |

| Dairy products | Wind | Others |

| Alcohol | Humidity | Exercise |

| Hot drinks | Menopause |

Ocular Rosacea

Ocular involvement has been reported in up to 58% of patients with rosacea and corneal involvement in 33%.3 As many as 90% of patients with ocular rosacea may have only very subtle skin changes, and in 20% of the cases, the ocular signs may precede skin involvement, making the diagnosis particularly challenging.1

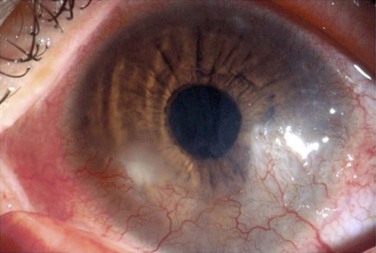

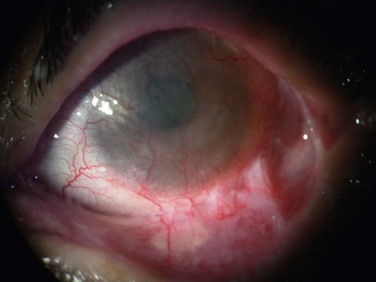

The findings in ocular rosacea are often non-specific, the most common being meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis (Fig. 22.2). A history of recurrent hordeolum and chalazia is common. Chronic conjunctivitis characterized by interpalpebral conjunctival hyperemia may be present. When corneal involvement is present, it typically begins with peripheral neovascularization, which may coalesce into characteristic triangular subepithelial marginal infiltrates (Fig. 22.3). These ‘spade-shaped’ inflammatory infiltrates can progress to the central cornea and lead to ulceration and perforation.2 Other reported ocular findings include dendritic keratopathy, iritis, episcleritis, scleritis and even scleral perforation (Fig. 22.4).3,8

Treatment

The initial management of rosacea is the identification and avoidance of trigger factors. With manifest early skin disease, the dermatologic manifestations of rosacea may be controlled with topical medications, such as metronidazole cream (0.75% and 1% formulations), azelaic acid gel 15% and sulfacetamide/sulfur.9,10 Other topical treatments include clindamycin, erythromycin, pimecrolimus, tacrolimus and tretinoin.10 When topical treatment alone is insufficient, systemic therapy should be initiated. Oral tetracyclines (500 mg twice daily) and doxycycline (40–100 mg daily from 8 to 16 weeks) have safely improved both skin and ocular rosacea. In 2006, the FDA approved a daily formulation of 40 mg doxycycline monohydrate (Oracea®, Galderma) for the treatment of rosacea. In unresponsive cases and those when tetracyclines are contraindicated, oral azythromycin (500 mg/day for 2 weeks) is considered an option. Oral isotretinoin (0.3 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) is recommended in more severe intractable cases. Vascular laser therapy and intense pulsed light can be used for treatment of resistant skin telangiectasias and persistent erythema.9,10

The management of mild ocular rosacea includes warm compresses and lid hygiene. Antibiotic ointments prescribed daily, at bedtime, may decrease eyelid flora and help soften collarettes. Moderate ocular rosacea should be treated with oral tetracycline or doxycycline in addition to local ocular therapy. As in the management of skin rosacea, tetracyclines may be initially administered 500 mg twice daily, or 250 mg four times daily for 3–4 weeks, and then tapered according to monitored clinical response. Doxycycline may be prescribed in a regimen of 40–100 mg once or twice daily for 6–12 weeks.10 Many patients present with flare-ups once the medication is discontinued and may, therefore, require long-term maintenance therapy at a titrated maintenance dose. Topical azithromycin can be useful as an off-label treatment for posterior blepharitis in ocular rosacea, particularly in patients intolerant to oral antibiotics mentioned earlier.

In cases of severe ocular surface inflammation, episcleritis, iritis and keratitis, topical steroids may prove beneficial but must be monitored for steroid-induced side effects.10 If corneal thinning or perforation occurs, surgical intervention may be necessary. Placement of cyanoacrylate glue, lamellar patch grafts, and penetrating keratoplasty are management options.

Ocular Cicatricial pemphigoid

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid) consists of a group of chronic and progressive autoimmune subepithelial blistering diseases that may affect the oral, ocular, pharyngeal, laryngeal, genital and anal mucosa.11 Characteristically, cicatricial pemphigoid demonstrates linear deposits of IgG, IgA, or C3 in the epithelial basement membrane on immunofluorescence microscopy or immunoperoxidase analysis.11

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) that involves primarily the ocular surface, as chronic and progressive cicatrizing conjunctivitis is referred to as ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP). However, ocular manifestations are present in 60% to 77% of all MMP patients.11,12

Epidemiology

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is considered a relatively rare disease, and its incidence is estimated to be between 1 in 15 000 and 1 in 60 000 ophthalmic patients.11 The average age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Women are more commonly affected than men (2 : 1 ratio). No geographical or racial predilection has been reported.11,12

Clinical Findings

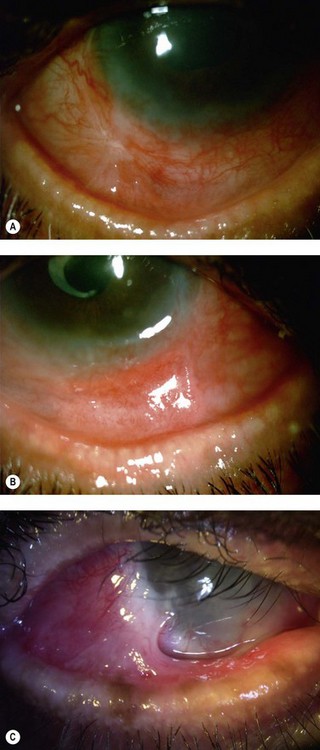

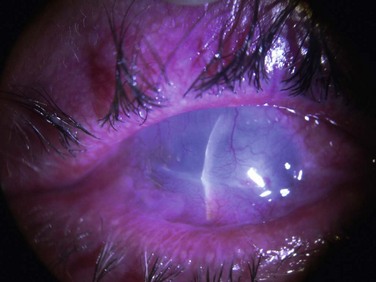

The findings in OCP are usually bilateral but may be asymmetric. Patients initially complain of non-specific symptoms: irritation, tearing, burning, foreign body sensation and excessive mucus production. Early signs include recurrent papillary conjunctivitis and fine subepithelial scarring at the tarsal conjunctiva (Fig. 22.5).11 Episodes of aggravation of the conjunctival inflammation followed by quiescent phases are observed throughout the course of the disease. With progression, worsening of the cicatrizing conjunctivitis, foreshortening of the conjunctival fornices and symblepharon formation (Fig. 22.6) occur. In more advanced cases, ankyloblepharon, cicatricial entropion, keratinization of the eyelid margins and trichiasis may develop.11

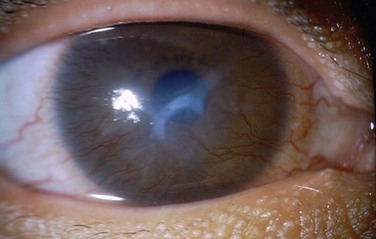

Corneal function is compromised in advanced disease as a result of chronic exposure, abnormal lid/globe contact and trauma from aberrant eyelashes. Dry eye also contributes to disruption of the corneal surface and is secondary to a combination of diminished aqueous tear production, mucin deficiency due to loss of conjunctival goblet cells and an accompanying predisposition to blepharitis. Corneal findings range from localized or diffuse punctate epitheliopathy to ulceration, opacification, neovascularization (Fig. 22.7) keratinization, and perforation that may lead to blindness. The compromised ocular surface is also at increased risk of bacterial and fungal keratitis.11

Figure 22.7 Severe corneal involvement in OCP.

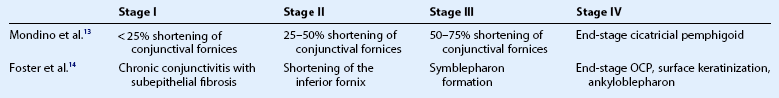

Staging Systems

There are two widely accepted staging systems: one described by Mondino et al. and another by Foster et al.13,14 Table 22.3 describes both systems. Since the disease is asymmetric, each eye should be evaluated separately.

Treatment

Dapsone is commonly used as the initial therapeutic agent in mild to moderate OCP.15,16 For severe or more rapidly progressive disease, more aggressive therapy with systemic corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents such as cyclophosphamide is recommended.11,15 Systemic treatments with methotrexate, cyclosporine A, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy have also been used effectively.11 Recommended doses are listed in Table 22.4. However, despite immunosuppression, some patients progress to end-stage ocular surface disease and eventual blindness.

Table 22.4

List of Main Systemic Immunosuppressive Agents Used for the Control of Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid

| Immunossuppressive Agent | Dose |

| Dapsone* | 50–200 mg/day |

| Prednisone | 1 mg/kg/day |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1–2 mg/kg/day |

| Azathioprine | 1–2 mg/kg/day |

| Methotrexate+ | 5–10 mg/week |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2–3 g/day |

*Contraindicated in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) deficiency due to risk of severe hemolytic anemia.

†Should be used with alternate-day folic acid (5 mg) to reduce the risk of adverse effects.

Local adjunct management includes preservative-free lubricant drops, and punctal occlusion may also improve dry eye. Topical tacrolimus and subconjunctival mitomycin C have also been employed to decrease conjunctival inflammation and reverse the formation of symblepharon respectively. Topical corticosteroids do not effectively control the progression of disease and should, therefore, be avoided as the sole treatment of acute flare-ups or as a sole prolonged therapeutic approach.11 Aberrant eyelashes may be treated with epilation or cryotherapy. Scleral contact lenses may be useful in protecting the ocular surface from trichiatic lashes and maintaining a wet corneal surface, permitting epithelial defects to heal.17

Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) constitute a group of acute, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases involving mucosal membranes and the skin. SJS is considered the less severe of the two conditions. Both are characterized by epidermal necrosis and mucosal involvement that can be induced by certain drugs or infections. A genetic predisposition has also been implicated.18 Both diseases are rare, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1.2–6 and 0.4–1.2 cases per million persons, respectively.19 Gender distribution is almost equal. Even with appropriate therapy, high mortality rates are observed in severe SJS and in TEN, and survivors suffer from long-term ocular surface complications that can lead to functional blindness.20

Etiology

The drugs most commonly associated with SJS and TEN are nevirapine, abacavir, lamotrigine, allopurinol, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, sulfonamide and beta-lactam antibiotics, tetracyclines, quinolones and NSAIDs. Infections associated with SJS and TEN include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, group A streptococci, hepatitis B virus, herpes simplex virus, Epstein–Barr virus, enterovirus and HIV.18

Clinical Findings

In 1993, a consensus definition was established, and the clinical criteria for SJS were defined as widespread macules or flat atypical target lesions and epidermal detachment on less than 10% of the body surface area (Fig. 22.8).18 Involvement of more than 30% of the body surface area was classified as TEN. Epidermal detachment between 10% and 30% was classified as SJS/TEN overlap.18 Initial manifestations are usually fever and malaise. Cutaneous erythema, vesicular eruption and hemorrhagic erosions of mucous membranes follow these initial findings.

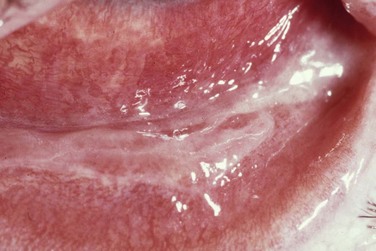

The ocular mucosa is involved in 69–82% of cases of SJS and in 50–88% of cases of TEN during the acute phase.19 Chronic ocular complications are present in up to 35% of patients.21 Other mucous membranes may also be affected, with the oral mucosa most commonly involved (Fig. 22.9). Internal organ involvement is uncommon.

Figure 22.9 Hemorrhagic erosions of oral mucosa in SJS.

Ocular Manifestations

The acute stage of ocular surface disease is is usually in the first 2 weeks after onset of symptoms. The initial ocular findings are lid edema, conjunctival inflammation and necrosis. Fifteen to seventy-five percent of the patients develop bilateral membranous conjunctivitis (Fig. 22.10) that is often difficult to control.21 Corneal involvement including epithelial defects and corneal infiltrates develop in approximately 25% of hospitalized patients.21

Figure 22.10 SJS with pseudomembranous conjunctivitis.

Chronic inflammation may also lead to extensive scarring and symblepharon formation (Fig. 22.11), ankyloblepharon and alterations of the lid margins including trichiasis, entropion, and punctal occlusion. Sight-threatening corneal sequelae result from blink-related microtrauma caused by these cicatricial complications.18 The destruction of goblet cells causing severe mucin deficiency dry eye and keratinization of the ocular surface are other common long-term complications.

Treatment

Identification and withdrawal of the inducing drug is crucial. If an infection is the cause, adequate antimicrobial treatment must be initiated promptly. A multidisciplinary approach is required in the management of the affected patient. In the acute stage, immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids, cyclosporine and intravenous immunoglobulins are controversial but are commonly employed.18,19 Immunosuppressive intervention may reduce inflammation, but may increase the risk of infection. Additional treatment is based on supportive care, including repletion of fluid loss, prevention of infection is necessary, and in the severest of cases, patients are managed similar to burn patients.

Ocular mucosal lesions require close monitoring. Topical prophylactic antibiotics and corticosteroids may be used for acute management. Ocular maintenance includes the frequent use of preservative-free lubricant drops and ointment. Corneal epithelial defects may be treated using bandage contact lenses. Intravenous steroid pulse therapy has shown promising results in preventing ocular complications.20

Transplantation of cryopreserved amniotic membrane within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms has shown promising results in promoting healing and reducing ocular surface inflammation and scarring.21

Prevention of symblepharon formation may reduce long-term complications. Removal of pseudomembranes, lysis of symblepharon using a glass rod and debridement of loose epithelium may improve the prognosis for the chronic stage.21

Treatment of long-term complications may require transplantation of limbal stem cells prior to keratoplasty. Because limbal stem cell deficiency is usually bilateral in SJS/TEN, transplantation of allogeneic limbal stem cells is frequently necessary, requiring systemic immunosuppression, and is associated with a guarded prognosis.22

Keratoprosthesis is another option for visual rehabilitation in more severe cases; however, the results in SJS are worse than in non-autoimmune disorders.22

Ectodermal Dysplasias

Ectrodactyly–Ectodermal Dysplasia-Cleft Lip (EEC) Syndrome

The EEC syndrome is characterized by ectrodactyly (lobster claw deformity of hands and feet), ectodermal dysplasia and cleft lip and palate (Fig. 22.12). It is an autosomal dominant condition, with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity, caused by mutations in the p63 gene.23,24

Figure 22.12 Lobster claw deformity of the hands in EEC syndrome.

Ocular Involvement and Therapy

The most common ocular manifestations are partial or complete absence of the meibomian glands and abnormalities of the lacrimal drainage system with resulting keratopathy.23 Anomalies of the lacrimal drainage system are present in up to 87% of patients and include absence or atresia of the puncta, incomplete development of the canaliculi, lacrimal sac or nasolacrimal ducts. Corneal involvement includes punctate keratopathy, stromal infiltration, opacification, thinning, pannus formation, neovascularization, and limbal stem cell deficiency.24 Recurrent erosions and corneal perforations have also been reported.25 Other ocular manifestations have been observed in EEC syndrome including telecanthus, micro/anophthalmia, trichiasis, entropion, madarosis (paucity of lashes and eyebrows) and blepharoconjunctivitis.25 Linear deposition of anti-basement membrane autoantibodies, similar to that seen in mucous membrane pemphigoid, was observed in four of six EEC syndrome patients with cicatrizing conjunctivitis.26

Ankyloblepharon–Ectodermal Defects-Cleft Lip/Palate (AEC) Syndrome

The AEC syndrome, or Hay–Wells syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant syndrome associated with mutations in the p63 gene.27 It is characterized by ankyloblepharon, cleft lip/palate and ectodermal defects such as sparse hair, nail and dental changes, impairment in sweating and skin erosions. Such cutaneous erosions, especially in the scalp, are characteristic features of neonates with this disorder and are often complicated by infections.27

Keratitis–Icthyosis–Deafness (KID) Syndrome

The KID syndrome is a rare congenital disorder characterized by keratitis, deafness, and skin manifestations that are better classified as erythrokeratoderma than as ichthyosis.28 Autosomal recessive and dominant cases have been reported.28 Mutations in the GJB2 gene coding for connexin 26, a component of gap junctions in epithelial cells, have been observed.29

Early in life, neonates develop a transient generalized erythema. The skin findings gradually progress into hyperkeratotic plaques located on the forehead, cheeks, perioral area, and scalp, and the patient develops a leonine facies.28,30 Hyperkeratosis may also be found on the trunk, elbows, knees and palmoplantar areas. During early infancy, the patient may develop keratitis and moderate to severe neurosensorial hearing impairment. There is also a predisposal to squamous cell carcinoma and increased risk of infections.28,30

Ocular Involvement and Therapy

Bilateral asymmetric corneal involvement with superficial and deep vascularization is present in more than 80% of patients (Fig. 22.13). Recurrent corneal erosions, corneal scarring, decreased tear production and limbal stem cell deficiency are other common signs.31 Lid margin alterations include meibomian gland dysfunction, trichiasis and keratinization. Sparse eyebrows and eyelashes are also frequently present.31

Figure 22.13 Corneal findings in KID syndrome.

Preservation of useful vision may be a challenge. Therapy includes lubricant drops and ointment, topical corticosteroids and cyclosporine, and oral doxycycline. Bandage contact lenses may be used for treatment of recurrent epithelial erosions.32 Recommended surgical procedures include amniotic membrane transplantation, superficial keratectomy and limbal allograft transplantation. Lamellar and penetrating keratoplasty as well as keratoprosthesis may be attempted for visual rehabilitation.32

References

1. Ghanem, VC, Mehra, N, Wong, S, et al. The prevalence of ocular signs in acne rosacea: comparing patients from ophthalmology and dermatology clinics. Cornea. 2003;22:230–233.

2. Alvarenga, LS, Mannis, MJ. Ocular rosacea. Ocul Surf. 2005;3:41–58.

3. Cohen, AF, Tiemstra, JD. Diagnosis and treatment of rosacea. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:214–217.

4. Wilkin, J, Dahl, M, Detmar, M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584–587.

5. Afonso, AA, Sobrin, L, Monroy, DC, et al. Tear fluid gelatinase B activity correlates with IL-1alfa concentration and fluorescein clearance in ocular rosacea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2506–2512.

6. Crawford, GH, Pelle, MT, James, WD. Rosacea: I. Etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327–341.

7. Meyer-Hoffert, U, Schröder, JM. Epidermal proteases in the pathogenesis of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:16–23.

8. Vieira, AC, Mannis, MJ. Spontaneous scleral perforation in ocular rosacea. Vision Pan-America. 2009;8(1):149–151.

9. Odom, R, Dahl, M, Dover, J, et al. Standard management options for rosacea, Part 1: Overview and broad spectrum of care. Cutis. 2009;84:43–47.

10. Odom, R, Dahl, M, Dover, J, et al. Standard management options for rosacea, Part 2: options according to subtype. National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. Cutis. 2009;84:97–104.

11. Kirzhner, M, Jakobiec, FA. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: a review of clinical features, immunopathology, differential diagnosis, and current management. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011;26:270–277.

12. Chang, JH, McCluskey, PJ. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: manifestations and management. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005;5:333–338.

13. Mondino, BJ, Brown, SI. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmol. 1981;88:95–100.

14. Foster, CS. Cicatricial pemphigoid. Trans Am Opthalmol Soc. 1986;84:527–663.

15. Chan, LS, Ahmed, AR, Anhalt, GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:370–379.

16. Bruch-Gerharz, D, Hertl, M, Ruzicka, T. Mucous membrane pemphigoid: clinical aspects, immunopathological features and therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:191–200.

17. Schornack, MM, Baratz, KH. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: the role of scleral lenses in disease management. Cornea. 2009;28:1170–1172.

18. Mockenhaupt, M. The current understanding of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:803–815.

19. Fu, Y, Gregory, DG, Sippel, KC, et al. The ophthalmologist’s role in the management of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ocul Surf. 2010;8:193–203.

20. Araki, Y, Sotozono, C, Inatomi, T. Successful treatment of Stevens–Johnson syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:1004–1011.

21. Gregory, DG. The ophthalmologic management of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2008;6:87–95.

22. Sayegh, RR, Ang, LP, Foster, CS, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:43–444.

23. Kaercher, T. Ocular symptoms and signs in patients with ectodermal dysplasia syndromes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:495–500.

24. Di Iorio, E, Kaye, SB, Ponzin, D, et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency and ocular phenotype in ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome caused by p63 mutations. Ophthalmoogy. 2012;119:74–83.

25. McNab, A, Potts, M, Welham, R. The EEC syndrome and its ocular manifestations. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:261–264.

26. Saw, V, Dart, J, Sitaru, C, et al. Cicatrising conjunctivitis with anti-basement membrane autoantibodies in ectodermal dysplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1403–1410.

27. Fete, M, vanBokhoven, H, Clements, S, et al. Conference report: international research symposium on ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip and/or palate (AEC) syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1885–1893.

28. Abdollahi, A, Hallaji, Z, Esmaili, N, et al. KID syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:11.

29. Schütz, M, Auth, T, Gehrt, A. The connexin26 S17F mouse mutant represents a model for the human hereditary keratitis–ichthyosis–deafness syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:28–39.

30. Gonzales, ME, Tlougan, BE, Price, HN, et al. Keratitis, icthyosis and deafness (KID) syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:11.

31. Meesmer, EM, Kenyon, KR, Rittinger, O, et al. Ocular manifestations of keratitis–icthyosis–deafness syndrome. Ophthalmol. 2005;112:e1–e6.

32. Djalilian, AR, Kim, JY, Saeed, HN, et al. Histopathology and treatment of corneal disease in keratitis, ichthyosis, and deafness (KID) syndrome. Eye (Lond). 2010;24:738–740.