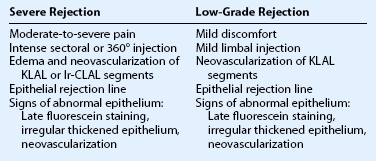

Ocular Surface Transplantation

Outcomes and Complications

Outcomes

The length of follow-up should be at least 1 year to ensure that the surface stability is due to repopulation by transplanted stem cells and not from the donor corneal epithelium that can survive up to 13 months postoperatively.1 Evaluation of shorter-term results may reveal a falsely high success rate initially. For example, an aniridic with conjunctivalization of the cornea and stromal scarring who undergoes a penetrating keratoplasty alone will initially experience dramatic improvement in vision. However, the ocular surface will inevitably fail when the donor epithelium sloughs and is replaced by conjunctivalization.

The preoperative diagnosis and severity of disease will affect outcomes. Schwartz et al.2 classified ocular surface disease based on the extent of limbal stem cell loss and the presence or absence of conjunctival inflammation. Patients with partial limbal stem cell deficiency and no conjunctival inflammation (e.g. contact-lens induced keratitis) will be easier to treat and have better outcomes than patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency and active conjunctival inflammation (e.g. Stevens – Johnson syndrome). The preoperative diagnosis will also affect the visual acuity achieved postoperatively. For example, an aniridic with foveal hypoplasia will not have the potential to achieve the same vision postoperatively as a chemical injured eye with a normal retina. Thus improvement in visual acuity is important, but cannot be the sole factor used to compare outcomes between studies.

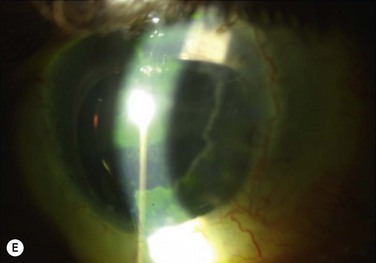

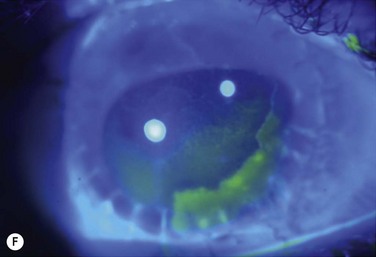

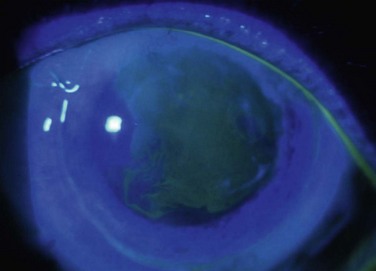

Studies utilize varying definitions of ocular surface stability. Most describe “failure” as the presence of a combination of the following signs of abnormal corneal epithelium: late fluorescein staining, persistent epithelial defects, neovascularization, conjunctivalization, and inflammation. Most describe “success” as the absence of the above signs and the presence of healthy transparent corneal epithelium. Between stability and failure is another category of ‘improved’ surface, defined as partial failure with areas of healthy corneal epithelium and areas of abnormal conjunctival epithelium on the cornea either in a mosaic or sectoral pattern. Figure 47.1 demonstrates partial limbal stem cell failure in a mosaic pattern.

Figure 47.1 Partial stem cell failure. Note the mosaic pattern of late fluorescein staining of abnormal epithelium.

CLAU

In unilateral LSCD, CLAU from the healthy fellow eye remains the procedure of choice, since rejection is not an issue and outcomes are excellent. Rao et al.3 described stable ocular surfaces in 15/16 (93.8%) eyes that underwent CLAU for ocular surface burns. Similarly, Yao et al.4 achieved a stable ocular surface in 32/34 (94.1%) of eyes with severe chemical or thermal burns who underwent simultaneous CLAU and deep lamellar keratoplasty with 27 ± 15.4 months of follow-up.

KLAL

The reported success rates of KLAL surgery vary widely, due to differences in preoperative diagnoses, length of follow-up, and immunosuppressive regimens used. Solomon et al.’s study5 of 39 eyes undergoing KLAL and amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) illustrates how length of follow-up affects success rates. They describe a progressive attrition in the survival of KLAL: 76.9% ± 6.7% at 1 year, 47.4% ± 11.7% at 3 years, and only 23.7% ± 17.7% at 5 years. Similarly, in Ilari and Daya’s study6 of 23 eyes undergoing KLAL, graft survival was 54.4% at 1 year, 33.3% at 2 years, and 27.3% at 3 years and only 21.2% at 5 years. Both studies had a similar mix of preoperative diagnoses with 30/39 eyes in Solomon’s study and 20/23 eyes in Ilari’s study having stage b or c disease (conjunctival involvement). The worse results in Ilari’s study may possibly be attributable to differing immunosuppressive regimens. Oral cyclosporine A (CSA) was used only in high-risk cases (9/20 patients), compared to Solomon’s study in which all patients received oral CSA indefinitely. In comparison, in Holland’s study7 of 31 eyes with aniridia, 74.2% achieved a stable ocular surface at 35.7 months of follow-up. They noted the effect of IS with 90.5% of eyes receiving systemic IS obtaining a stable ocular surface, whereas only 40.0% of eyes receiving systemic IS achieving surface stability. The higher success rate in this study may possibly be attributable to all cases being aniridic and thus having no conjunctival involvement (stage a disease).

lr-CLAL

There are few studies that describe the success rates of lr-CLAL. In a study by Gomes et al.8 of 10 eyes undergoing combined lr-CLAL and amniotic membrane transplantation, six eyes had successful ocular surface reconstruction with 19 months (range 8–27 months) follow-up. Only patients with less than 75% HLA compatibility between recipient and donor received oral immunosuppression with CSA. In a study by Javadi et al.9 32 eyes had lr-CLAL and 40 eyes had KLAL performed for mustard gas-induced LSCD. They found that the rejection-free graft survival rate was 39.1% in the lr-CLAL group and 80.7% in the KLAL group 40 months postoperatively. This result may be explained by the different IS regime used in their two groups: the lr-CLAL group received 1 year of oral CSA, compared to the KLAL group receiving oral CSA for 1.5 to 2 years in addition to mycophenolate mofetil for at least 6 months. Also, they did not use HLA-matching for their lr-CLAL group. The results of their study emphasize the importance of preoperative HLA-matching and postoperative IS in lr-CLAL. At the authors’ institute, combined lr-CLAL and KLAL, ‘the Cincinnati procedure,’ is used to treat patients with the most severe ocular surface failure, having both severe LSCD and conjunctival deficiency, such as in Stevens – Johnson syndrome. In our study10 of 19 eyes undergoing combined lr-CLAL/KLAL, the ocular surface was stable in 54.2%, improved in 33.3%, and failed in 12.5% of eyes with follow-up of 43.4 months (range 12.2 to 125.5 months).

CLET

Shortt et al.11 performed a review of 17 papers of CLET techniques using autograft, allograft, or oral mucosal sources of stem cells. A total of 131 of 170 eyes (77%) treated for partial or total LSCD reported improvement in clinical parameters, with little difference in the rate of improvement between autografts (86/114, 75.4%) and allografts (45/56, 80%). However, the authors warned against interpretation of these results as the outcome measures used to define successful treatment were poorly described by most studies, and lacked objectivity, as there was no comparison of defined pre- and post-treatment parameters.

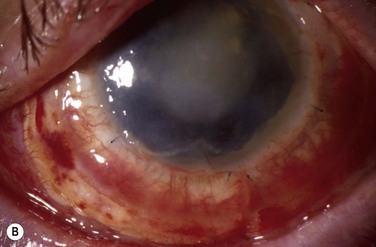

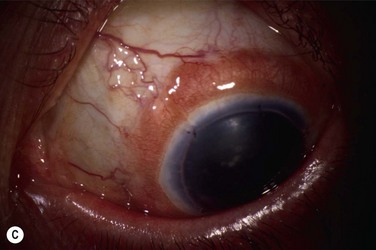

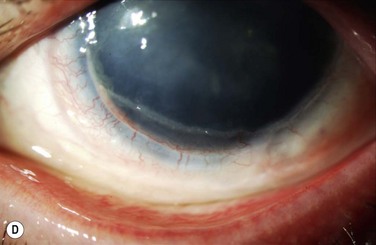

Complications

Immunologic rejection of allograft OSST is the most important cause of stem cell failure. In contrast to corneal transplants that have relative immune privilege, limbal tissue is highly vascularized and rich in antigen-presenting cells and Langerhans cells. Pathologic findings in rejected KLAL specimens indicate that rejection is a T-cell mediated phenomenon.12 Rejection may present clinically as severe or low grade, as shown in Table 47.1 and Figure 47.2. In the authors’ study13 of 222 eyes with mean follow-up of 62.7 months (range 12.0–158.3 months), rejection occurred in 31.1% (69/222) of patients at a mean of 19.3 months postoperatively (range 0.2–93.1 months). This demonstrates that rejection is a long-term concern, due to the perpetuation of donor epithelial cells within the donor limbus. Risk factors for rejection were younger age, KLAL alone (versus lr-CLAL or combination of lr-CLAL/KLAL), and noncompliance with IS. Patients who rejected had a worse outcome despite treatment with increased immunosuppression and repeat OSST if necessary: at the final follow-up visit only 36.6% (26/69) of patients had a stable ocular surface, compared to 71.9% (110/153) of those that did not reject. Even though the transplant may not immediately fail at the time of rejection, these patients have a higher rate of ocular surface failure in the long term.

Patients should be adequately immunosuppressed to prevent rejection. At the authors’ institution, immunosuppression is managed in conjunction with the renal transplant team, using a regimen of short-term oral prednisone (tapered over 1 to 3 months) and longer-term tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (tapered over 2 to 3 years).14 Patients’ tacrolimus levels are monitored to ensure therapeutic effect and compliance, and patients are educated preoperatively regarding the necessity and importance of immunosuppression for a successful transplant. If rejection is suspected, the patient should be treated aggressively with increased topical and systemic immunosuppression. Patients with a prior history of rejection should be maintained on low-dose immunosuppression indefinitely if systemically tolerated.

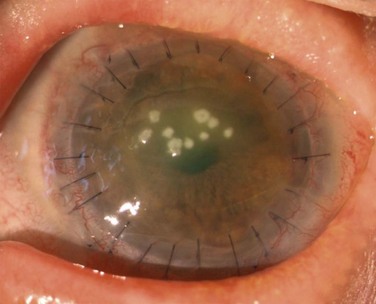

Microbial Keratitis

Patients with OSST and keratoplasty are particularly susceptible to microbial keratitis. The combination of the presence of epithelial defects and the use of immunosuppression (both topical and systemic) sets the environment for opportunistic infections, especially fungal keratitis. Figure 47.3 illustrates a fungal keratitis in an eye that had undergone OSST. In Solomon’s study5 of 39 eyes undergoing KLAL, three of 24 eyes that had also undergone PK developed microbial keratitis. Two corneal grafts that were severely infected by Candida species required therapeutic keratoplasty, and one eye had coagulase negative Staphylococcus. In the authors’ experience, fungal keratitis is difficult to eradicate medically and often requires an early therapeutic keratoplasty. Medical treatment consists of aggressive topical and oral antifungals, cessation of all topical steroids, and reduction of the systemic immunosuppression. If the infection cannot be controlled medically, an early therapeutic keratoplasty should be performed before the infiltrate reaches the graft – host interface.

Etiology of Failure

Concurrent cicatrizing eyelid pathology that occurs in these diseases contributes to OSST failure and should be addressed prior to or at the time of OSST surgery. Disorders of the lid – lash complex may cause microtrauma and perpetuate chronic inflammation through the mechanical rubbing of lashes against the ocular surface. Ectropion or lagophthalmos can cause exposure keratopathy and delay healing after OSST. Conjunctival involvement may result in aqueous and mucin deficiency, and in the most severe cases keratinization of the surface. Holland’s study15 found that keratinization of the conjunctiva was a risk factor of OSST failure, as was a Schirmer test of 2 mm or less at 5 minutes without anesthesia.

References

1. Krachmer, JH, Alldredge, OC. Subepithelial infiltration. A probable sign of corneal transplant rejection. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2234–2237.

2. Schwartz, GS, Gomes, JAP, Holland, EJ. Preoperative staging of disease severity. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, eds. Ocular surface disease: medical and surgical management. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

3. Rao, SK, Rajagopal, R, Sitalakshmi, G, et al. Limbal autografting: comparison of results in the acute and chronic phases of ocular surface burns. Cornea. 1999;18:164–171.

4. Yao, YF, Zhang, B, Zhou, P, et al. Autologous limbal grafting combined with deep lamellar keratoplasty in unilateral eye with severe chemical or thermal burn at late stage. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:2011–2017.

5. Solomon, A, Ellies, P, Anderson, DF, et al. Long-term outcome of keratolimbal allograft with or without penetrating keratoplasty for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1159–1166.

6. Ilari, L, Daya, SM. Long-term outcomes of keratolimbal allograft for the treatment of severe ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1278–1284.

7. Holland, EJ, Djalilian, AR, Schwartz, GS. Management of aniridic keratopathy with keratolimbal allograft: a limbal stem cell transplantation technique. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:125–130.

8. Gomes, JA, dos Santos, MS, Cunha, MC, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for partial and total limbal stem cell deficiency secondary to chemical burn. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:466–473.

9. Javadi, MA, Jafarinasab, MR, Feizi, S, et al. Management of mustard gas-induced limbal stem cell deficiency and keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1272–1281.

10. Biber, JM, Skeens, HM, Neff, KD, et al. The Cincinnati procedure: technique and outcomes of combined living-related conjunctival limbal allografts and keratolimbal allografts in severe ocular surface failure. Cornea. 2011;30:765–771.

11. Shortt, AJ, Secker, GA, Notara, MD, et al. Transplantation of ex vivo cultured limbal epithelial stem cells: a review of techniques and clinical results. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:483–502.

12. Daya, SM, Dugald Bell, RW, Habib, NE, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings in human keratolimbal allograft rejection. Cornea. 2000;19:443–450.

13. Ang, AY, Chan, CC, Biber, JM, et al. Ocular surface stem cell transplantation rejection: incidence, characteristics, and outcomes. Cornea. 2013;32:229–236.

14. Holland, EJ, Mogilishetty, GM, Skeens, HM, et al. Systemic immunosuppression in ocular surface stem cell transplantation: Results of a 10-year experience. Cornea. 2012;31:655–661.

15. Holland, EJ. Epithelial transplantation for the management of severe ocular surface disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1996;19:677–743.