Ocular Surface Neoplasias

Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is an umbrella term used to describe cancerous epithelial lesions of the cornea and conjunctiva, ranging from dysplasia to carcinoma-in-situ to invasive squamous cell carcinoma.1 The term conjunctival and corneal epithelial neoplasia (CIN) describes varying degrees of dysplasia confined to the surface epithelium, and when it is full thickness is called carcinoma-in-situ. When invading the basement membrane, the term squamous cell carcinoma applies.

Epidemiology

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) has an estimated incidence in the United States of 0.03 per 100 000 persons.2 Higher incidences have been reported in other parts of the world with more sun exposure, with an estimated incidence of 1.9 per 100 000 persons in Australia3 and 3.5 per 100 000 persons in Uganda.4 It is the most common, non-pigmented ocular surface tumor.5 OSSN occurs more commonly in middle-aged or elderly individuals. Lee and Hirst reported an average age of occurrence of 56 years, with a range of 4 to 96 years.3 Patients with xeroderma pigmentosum and human immunodeficiency virus develop OSSN at younger ages.6,7 It is also more common in fair-skinned individuals and males, with a fivefold higher incidence in Caucasian males.2

Etiology

Solar Ultraviolet Radiation

Numerous epidemiologic studies have identified ultraviolet B (UV-B) light as a major etiologic factor in the pathogenesis of OSSN.1,2,8,9 Newton et al. demonstrated a 49% decline in the rate of OSSN for each 10-degree increase in latitude, due to the decrease in solar ultraviolet radiation with increasing latitude.9

In a case control study, Lee at al. identified fair skin, pale irises, a propensity to sunburn, and prolonged sun exposure in early life as risk factors for OSSN.8

UV-B light is known to cause DNA damage through formation of pyrimidine dimers.10 Patients with xeroderma pigmentosum, who are more susceptible to the effects of sunlight, due to a defect in DNA repair mechanisms, have increased incidences of OSSN.6 It has been proposed the effect of UV-B radiation may be due to the overexpression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene.11

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection

The increased frequency of OSSN since the advent of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, strongly suggests the role of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in increasing the risk of developing OSSN.7,12 In a study in Malawi, 79% of patients diagnosed with OSSN were found to be HIV positive. In HIV patients, OSSN occurs at a younger age and tends to be more aggressive.12 This emphasizes the importance of testing for HIV in younger patients diagnosed with OSSN, as it may be the first presenting sign of the disease.7,12

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection

Whereas, the role of HPV in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer has been well established, the role of HPV as an etiologic factor in OSSN remains unclear. Various studies have demonstrated an association between HPV subtypes and OSSN,13,14 while other studies have failed to show any association.15,16 Further evidence confusing the etiologic role of HPV includes the presence of unilateral OSSN in patients with bilateral conjunctival HPV DNA, the presence of HPV in normal conjunctival tissue, and the persistence of HPV infection many years after eradication of OSSN 13,17,18 It is possible HPV may not act alone but may require a cofactor, such as HIV or UV-B light, in order to cause disease.17,19

Other Etiologic Factors

Other risk factors reported in the literature include heavy smoking and exposure to petroleum derivatives.20,21 It has also been reported in association with pterygium.22 Finally, there have been case reports of OSSN in immunosuppressed patients with neoplasia (lymphoma, leukemia) and following organ transplantation.23

Clinical Features

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia, most commonly presents with foreign body sensation, irritation, redness, or a growth on the ocular surface.1 Lesions are typically unilateral and slow growing. More than 95% of these lesions occur in the mitotically active limbal region, within the sun-exposed interpalpebral zone.24,25 More rarely, it can involve the cornea or bulbar conjunctiva alone. It also can occasionally involve the forniceal or palpebral conjunctiva or involve the bulbar conjunctiva or cornea alone. The lesion may be fleshy and markedly elevated, sessile, or minimally elevated.

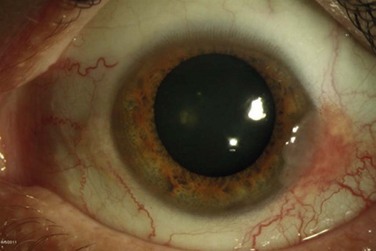

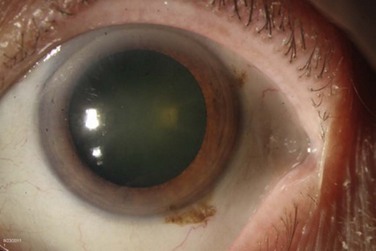

The classic macroscopic appearance of OSSN is a gelatinous limbal mass with feeder vessels. It can be also have a papilliform appearance with a strawberry-like papillary growth at the limbus or demonstrate leukoplakic changes. (Fig. 19.1).1,26 Nodular and diffuse are two other appearances that have been described. The nodular form is well circumscribed and rapidly growing, while the diffuse form may mimic a chronic conjunctivitis and has a tendency for metastasis to regional lymph nodes.1

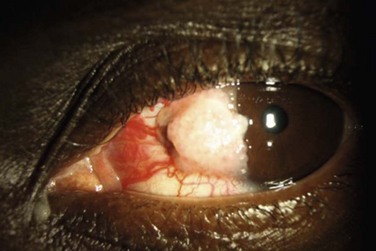

It may be difficult to distinguish CIN from squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) based on clinical examination. SCC may be larger and more elevated with a feeder vessel, and adherent to the underlying tissues (Fig. 19.2).27,28 CIN lesions tend to be freely mobile over the sclera.

Differential Diagnosis

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia is most commonly misdiagnosed as pinguecula, pterygium, actinic keratosis and squamous papilloma, or episcleritis.29 Hirst et al. found in a histopathologic review of 533 pterygium specimens, 9.8% were found to have evidence of dysplasia.30 This supports the notion that all excised pterygium specimens should be submitted for pathology at the time of removal. The differential diagnosis includes other benign entities, such as pyogenic granuloma, inflammatory pannus, phlyctenulosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Amelanotic melanoma, sebaceous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma can also rarely simulate OSSN.29,31 Keratoacanthoma can be distinguished by its rapid growth over several months.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Exfoliative Cytology

Papanicolaou smear cytology is widely accepted as a valuable diagnostic tool in the detection of cervical cancer and has also been described to be useful in the diagnosis of external ocular tumors.32 A cytobrush or spatula is used to scrape the surface of the suspicious lesion and the cells are sent on a slide to pathology, fixed with 95% alcohol, and stained using a Papanicolaou technique. A major disadvantage is that the superficial nature of the sample may lead to missing the tumor cells. In addition, with this technique, it is not possible to determine the degree of tissue invasion or localize the tumor.26

Impression Cytology

Impression cytology is another technique that can be used to obtain cells from the surface of the conjunctival lesion, with its use first described in limbal tumors in 1954.33 In this technique, a filter paper composed of cellulose acetate, millipore filter paper, or a biopore membrane device, is placed on the ocular surface using gentle pressure and subsequently fixed and stained with the Papanicolaou stain. Nolan and Hirst reported a sensitivity for the diagnosis of OSSN with impression cytology of only 78%.34 Unlike exfoliative cytology, this method allows for localization of the lesion with preservation of cell-to-cell relationships. Similar to exfoliative cytology, only superficial cells are obtained and thus, the presence of invasion cannot be determined.

The advantage of both impression and exfoliative cytology is that they there are relatively simple, painless, and minimally invasive methods, which can be performed in the office after the application of topical anesthesia. They may also be a simple method for the detection of recurrences.32

Confocal Microscopy

There have been several reports of in vivo confocal microscopy as a useful tool in the diagnosis of OSSN.35,36 Confocal microscopy allows for real-time, noninvasive imaging at the cellular level by optical microscopic sectioning of the ocular surface. Malandrini and colleagues described a case of CIN, with a clear distinction between the healthy and pathological epithelium on confocal microscopy. The epithelial cells near the lesion were larger in size, more irregularly shaped, and demonstrated brighter nuclei.35

Ultra-High Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography

More recently, ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography (UHR- OCT) has been described as a noninvasive diagnostic tool to evaluate ocular surface lesions. This technology allows for morphologic visualization of the corneal architecture, with an axial resolution of 2–3 µm. Kieval et al. found that UHR-OCT of pterygia and OSSN lesions demonstrated a high degree of correlation to histopathological specimens.37 The UHR-OCT of OSSN showed thickened epithelium with an abrupt transition from normal to neoplastic tissue (Fig. 19.3). UHR-OCT of pterygia demonstrated a normal thin epithelium, with thickening of the underlying subepithelial mucosal layers. The sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between OSSN and pterygia using UHR-OCT with an epithelial thickness cutoff of 142 µm was 94% and 100%, respectively.37

Pathology

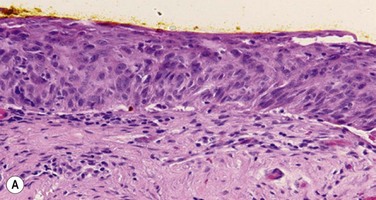

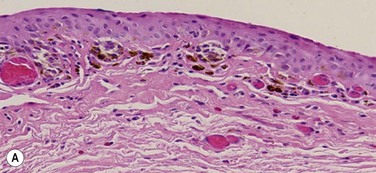

Pre-invasive OSSN lesions are classified as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the extent of replacement of the epithelium by dysplastic cells that lack normal maturation (Fig. 19.4A). The cells are usually long and elongated. Mild dysplasia (CIN grade I) is when the dysplasia is confined to the lower one-third of the epithelium. In moderate dysplasia (CIN grade II), the abnormal cells extend to the middle third of the epithelium. Severe dysplasia (CIN grade III) involves the full-thickness epithelium with total loss of the normal cellular polarity and is also known as CIS. The epithelial basement membrane is intact.

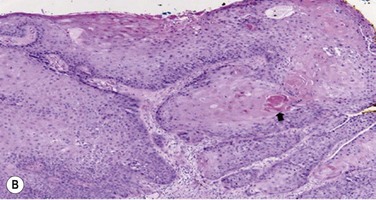

Most conjunctival SCCA’s are well differentiated, demonstrating individually keratinzed cells (dyskeratosis) and concentric collections of keratinized cells (horn cells). Well-differentiated tumors demonstrate varying degrees of cellular pleomorphism with hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli and the presence of mitotic figures. Hyperparakeratosis and parakeratoses are also present (Fig. 19.4B).26,27

Histopathologic variants with more aggressive behavior are spindle cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and adenoid squamous cell carcinoma.26

Treatment

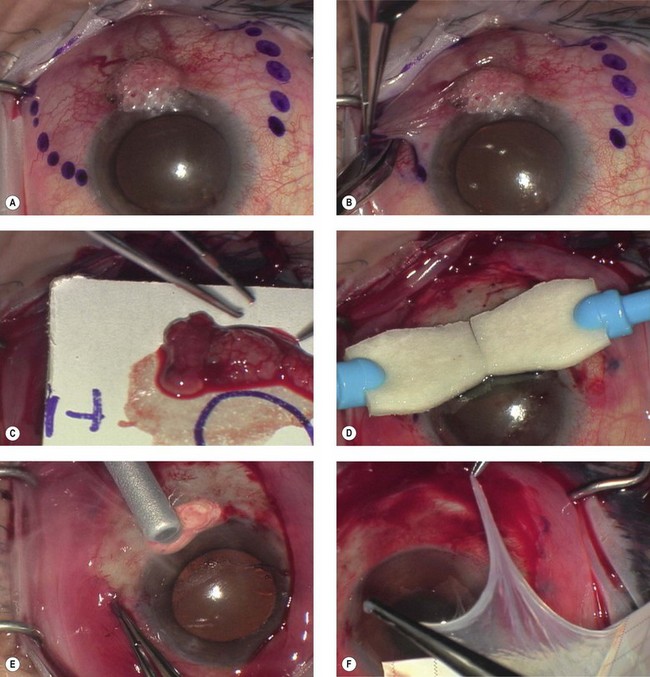

Surgical Excision with Cryotherapy

Surgical excision, alone or in combination with medical therapy, is the most established treatment for OSSN. With surgical excision alone, the rate of recurrence is high, ranging from 5% to 33% with negative margins and up to 56% with positive surgical margins.26 A ‘no touch’ technique, in which touching the tumor with any instruments is avoided, reduces the risk of tumor seeding.38 Wide margins of 4–6 mm should be obtained. If the lesion extends into the sclera or cornea, a superficial keratectomy or partial-thickness sclerectomy may be needed.

Absolute alcohol epitheliectomy of the involved cornea is also recommended.

To delineate the margins of the lesion, rose bengal staining or UHR-OCT can be used. However, there is evidence that the microscopic signs of OSSN may extend beyond the macroscopic border the tumor,17 and many surgeons prefer adjuvant cryotherapy to the limbus and conjunctival margins at the time of excision.

Cryotherapy is thought to work initially by its thermal effect and also by obliteration of the microcirculation, resulting in ischemic infarction and a double freeze–slow thaw technique is recommended.1 The rates of recurrence with excision and cryotherapy have been reported to be lower than with excision alone, at about 12%.19,39 Excess cryotherapy should be avoided, since side effects include iritis, abnormal intraocular pressure, sector iris atrophy, hyphema, ablation of the peripheral retina, corneal neovascularization, and limbal stem cell deficiency.1,19

Since wide excisions are recommended, surgical excision often results in large defects, necessitating the use of a conjunctival autograft, an oral mucosal graft, or an amniotic membrane transplant. A number of studies have described successful reconstruction of the ocular surface with preserved amniotic membrane after excision of CIN, SCC, primary acquired melanosis, and melanoma.40,41 Amniotic membrane is a helpful technique, since defects of any size can be closed, and the membrane has additional properties of promoting epithelialization, and reducing neovascularization, scarring and fibrosis.40 In addition, the use of fibrin glue, instead of sutures to secure the membrane reduces inflammation.42 The use of a conjunctival autograft of adequate size from either the same or opposite eye is an option. Care needs to be taken to avoid large areas of stem cell removal, which may lead to scarring, symblepharon, and limbal stem cell deficiency. Thick buccal or labial grafts are generally reserved for cases with extensive symblephara and might potentially interfere with the ability to observe for recurrence of the underlying tumor.40

In summary, the preferred technique for OSSN removal involves excision of the tumor with wide margins, absolute alcohol epitheliectomy of the involved cornea, cryotherapy using a double freeze–slow thaw cycle to the limbus and conjunctival margins, and amniotic membrane transplantation (Fig. 19.5).

Antimetabolites

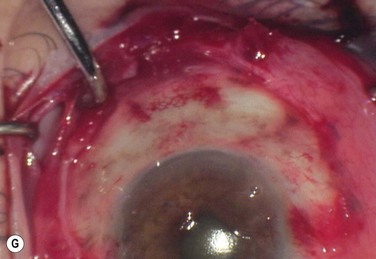

MMC is an alkylating agent that inhibits DNA synthesis by the production of free radicals. It is used as a topical drop at concentration of 0.02% or 0.04% four times daily for 7 to 14 days in cycles. One week is allowed between cycles to minimize ocular toxicity. Excellent responses raging from 87.5% to 100% have been reported.43,44 Side effects include conjunctival hyperemia, blepharospasm, corneal punctate erosions, punctal stenosis, and limbal stem cell deficiency.44 Punctal plugs should be used to prevent punctal stenosis. Refrigeration is required and at our institution (Bascom Palmer Eye Institute) the cost is about US$225 per bottle.

5-FU is a pyrimidine analogue that inhibits the incorporation of thymidine into DNA, during the S-phase of the cell cycle. It is prescribed as a 1% topical solution applied four times daily for 4 to 7 days, with 30–35 days off for a total of two to five cycles.45 It has also been used for 4 weeks continuously.46 5-FU may lead to ocular surface irritation and thus, 4 to 7 days a month dosing is preferred by the authors. Unlike MMC, it does not require refrigeration and is less costly (about US$75 per bottle).

Interferon α-2b

Interferon α is a family of proteins, secreted by leukocytes, with antiviral and antineoplastic properties. It has been used in the treatment of many cancers, including cervical intraepithelial neoplasia,47 cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,48 and renal cell carcinoma.49 It has also been used to treat viral lesions, including hepatitis B and C, and condyloma acuminata.50 INF α-2b is a recombinant protein that has been used in the treatment of OSSN with success rates of above 80%.51,52 It can be given as topical eye drops or a subconjunctival injection, and a combination of both may be used.

Topical INF α-2b is much better tolerated than MMC and 5-FU. Interferon drops are very gentle and well tolerated. Reported side effects include mild conjunctival hyperemia and follicular conjunctivitis.53 Topical INF α-2b (1 million IU/mL) is dosed four times daily and given continuously until the tumor resolves. It is not cycled like MMC and 5-FU and the cost is about US$225 per month for the eye drops. On average, the time on the medication is 3 months. Figure 19.6 demonstrates the case of a 54-year-old male with OSSN, which resolved after 12 weeks of treatment with topical INF α-2b.

Interferon can also be given as subconjunctival injections. These may be given once to thrice weekly. Side effects of subconjunctival delivery include fever, chills, headache, myalgias, and arthralgias, which may last a few hours after the injection. Acetaminophen at a dose of 1000 milligrams every 6 hours is helpful. The time to tumor resolution is generally faster with subconjunctival injections (average 1.4 months), as compared to resolution topical INF α-2b drops (average 2.8 months).51,52 The subconjunctival dose is 0.5 mL (3 million IU/0.5 mL solution) repeated one to three times a week until clinical resolution occurs.

A comparison of MMC, 5-FU, and INF-α-2b are summarized in Table 19.1.

Prognosis

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia is considered a low-grade malignancy with a good prognosis, as the tumor is generally slow growing. Local recurrences are common, with most occurring within the first 2 years.1 Intraocular invasion and metastasis are extremely rare. Intraocular invasion is thought to occur by tumor cells entering the eye at the limbus and invading the trabecular meshwork, anterior chamber, ciliary body, iris and choroid.54 Sites of metastasis include the parotid gland, submandibular and submaxillary glands, preauricular, cervical lymph nodes, lungs, and bone and are related to a delay in management.55

Melanoctyic Tumors

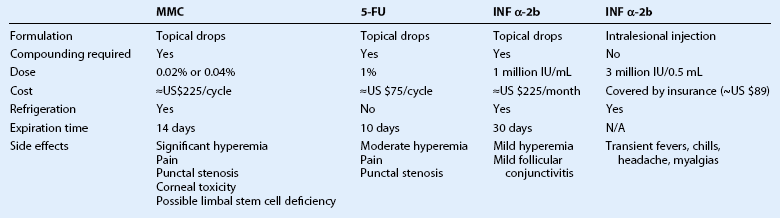

Conjunctival melanoma is a tumor that arises from the melanocytes in the basal layer of the conjunctival epithelium. Other melanocytic lesions of the ocular surface include conjunctival nevi, racial melanosis, ocular melanocytosis, and primary acquired melanosis. Clinical features of each are summarized in Table 19.2.

Conjunctival Nevus

A conjunctival nevus is a pigmented or nonpigmented mass, which is mobile, circumscribed, and elevated. It is the most common conjunctival tumor, accounting for 28% of all conjunctival tumors and 52% of those classified as melanocytic tumors.5 Nevi usually present in childhood or early adolescence, most commonly located in the bulbar conjunctiva, caruncle, or plica semiluminaris. Intralesional cysts are commonly visible at the slit lamp (Fig. 19.7). Growth may occur with hormonal changes, such as during puberty or pregnancy, but otherwise the lesion size remains stable. In a study of 410 patients with conjunctival nevi, 1% showed evolution into melanoma over an interval of 7 years.56

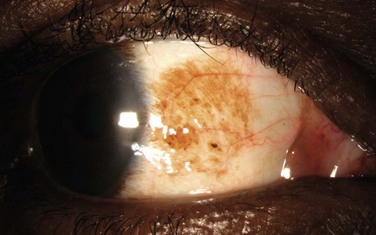

Primary Acquired Melanosis

Conjunctival primary acquired melanosis (PAM) accounts for 11% of all conjunctival tumors and 21% of melanocytic lesions.5 It presents as a unilateral, patchy area of conjunctival pigmentation in middle-aged or elderly adults with fair skin (Fig. 19.8). The pigmentation can wax or wane over time.28 PAM with atypia can only be distinguished from PAM without atypia by histologic examination. In a study of 311 eyes with PAM, lesions without atypia or mild atypia showed 0% progression to melanoma and lesions with severe atypia showed progression to melanoma in 13%.57 In addition, those with a greater extent of PAM in clock hours had a greater risk for transformation into melanoma. In the Armed Formed Institute of Pathology series of 41 patients with PAM, progression to melanoma occurred in 0% with PAM without atypia and in 46% if the PAM showed microscopic evidence of atypia.58

Melanoma

Conjunctival melanoma is a rare tumor, accounting for 2–5% of ocular melanomas.59 It accounts for 13% of all conjunctival tumors and 25% of all melanocytic tumors.5 The estimated incidence in the United States is 0.5 per million.60 There is evidence that the incidence of conjunctival melanoma has been increasing in the United States, Sweden, and Finland.61–63 Based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study by the National Cancer Institute, the incidence of conjunctival melanoma has increased from 0.22 cases per million, per year in 1973–1979, to 0.46 in 1990–1999.62 This increase was most notable in white men.

Conjunctival melanoma is more common in middle-aged and elderly people, with the majority of patients between 40 and 70 years of age. 59 It has been reported rarely in children, with age 10 being the youngest age of diagnosis.59,64 It is also uncommon in non-white populations. In a series of 382 patients with conjunctival melanoma, 94% patients were white, 3% were black, and 3% were Hispanic or Asian.64

Etiology

Unlike cutaneous melanoma, there is no clear evidence regarding the association of UV exposure and conjunctival melanoma. A study in Sweden demonstrated an increase in the incidence of conjunctival melanoma in sun-exposed areas (bulbar, limbal and caruncular conjunctiva) over time, while the incidence in non-sun-exposed areas (tarsal and forniceal conjunctiva) remained constant. 61 Conjunctival melanoma can arise from a conjunctival nevus (7%), primary acquired melanosis (74%), or de novo (19%).64

Clinical Features

The clinical appearance of conjunctival melanoma is variable. It generally occurs as a brown to tan elevated lesion that is relatively immobile (Fig. 19.9). Prominent feeder vessels might be present. As the lesion frequently arises from PAM, surrounding flat PAM might be present. The most frequently involved locations are the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus. Less commonly, the fornix, palpebral conjunctiva, and caruncle may be involved.64 The majority of melanomas are pigmented (59%), but up to 20% are non-pigmented (amelanotic) and 21% are mixed.64 The cornea may be involved by growth of the tumor cells from the limbus, but the tumor cells generally do not penetrate Bowman’s layer.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma includes other pigmented lesions, such as nevi, racial melanosis, ocular melanocytosis, and PAM. Nevi rarely present in the palpebral conjunctiva or fornix and thus, any lesions presenting in these area should be removed. Unlike PAM, racial melanosis occurs in darkly pigmented individuals and is bilateral. The pigmentation is usually around the limbus, often for 360 degrees (Fig. 19.10). Ocular melanoctyosis is a congenital pigmentation of the sclera and periocular skin that can be mistaken for primary acquired melanosis. However, the gray-brown pigment is located beneath the conjunctival tissue. Patients with this condition have a 1 : 400 risk of developing uveal melanoma in their lifetime.65

Epithelial lesions, such as squamous papilloma and OSSN, can acquire pigment in darkly pigmented individuals and resemble melanoma.66 Rarely, there can be extraocular extension from a ciliary body melanoma or melanocytoma to the epibulbar surface.67 Metastatic cutaneous melanoma to the conjunctiva has also been reported. 68 Other lesions in the differential include staphylomas, hematic cysts, foreign bodies, blue nevus, subconjunctival hematomas, ochronosis deposits in patients with alkaptonuria and adreonchrome pigment in the inferior fornix in patients previously on epinephrine eyedrops.69,70

Diagnostic Work-Up

Any pigmented lesion presenting in adulthood demonstrating growth or change in pattern of pigmentation or vascularity should undergo excisional biopsy.59 Slit lamp clinical photos are helpful in monitoring for any changes.

Definitive diagnosis of conjunctival melanoma can only be made with surgical excision histopathology. Incisional biopsy should not be performed on a suspected conjunctival melanoma, as it has been associated with increased risk of tumor recurrence, likely due to seeding of cells.71 Ultrasound biomicroscopy can be useful in detecting the presence of intraocular invasion and in measuring tumor dimensions.72 Anterior segment OCT can detect intralesional cysts in conjunctival nevi.73

All patients with melanoma should be referred to an oncologist for a complete systemic work-up. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and orbits is important in cases of suspected orbital extension and to rule out brain metastasis.74 Sentinel lymph node biopsy to detect micrometastatic disease, is currently being investigated, but long-term survival benefit of this has not yet been established. Some advocate the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy when the risk of metastasis is high, such as with non-limbal tumors and with a tumor thickness greater than 2 mm.75

Pathology

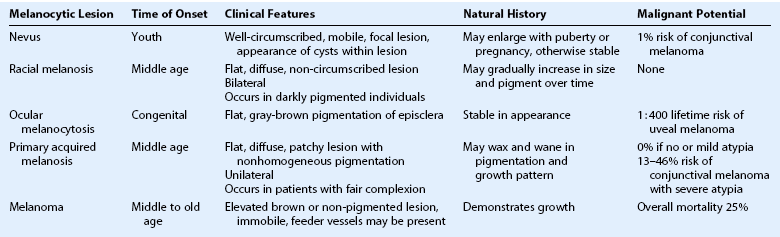

Conjunctival melanoma is composed of malignant melanocytic cells with nuclear atypia, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm. Jakobiec and colleagues described four types of atypical melanocytes found in conjunctival melanomas: small polyhedral cells; large, round epitheloid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm; spindle cells; and balloon cells.27,76 The abnormal cells initially begin in the basal area of the epithelium, but then invade the stroma where they gain access to conjunctival lymphatic vessels.27 There may be microscopic evidence of a pre-existing nevus or PAM.

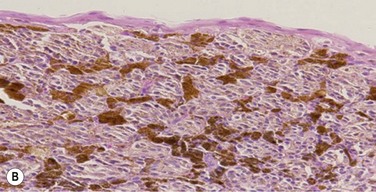

PAM without atypia is defined as increased pigmentation of the conjunctival epithelium, with or without an increase in the melanocytes. The melanocytes are confined to the basal layer of the epithelium and do not show any cytologic atypia. In PAM with mild atypia, the melanocytes show cellular atypia but are still confined to the basal layer of the epithelium. PAM with severe atypia is defined by the presence of epithelioid cells and/or extension of the atypical melanocytes into the more superficial layers of the epithelium (pagetoid spread) (Fig. 19.11).77

Histopathologic features predictive of worse prognosis include pagetoid spread, the presence of epithelioid cells, histologic evidence of lymphatic invasion, and high numbers of mitotic figures.58,59,70 As demonstrated with cutaneous melanomas, depth of invasion is a major prognostic factor. Immunohistochemical markers, such as S100, Melan A, or HMB-45, can be used to aid in the diagnosis.78

Treatment

The primary treatment for conjunctival melanoma is surgical excision, with wide margins (4–6 m), using a ‘no touch’ technique, a partial sclerectomy if the tumor is adherent to the sclera, absolute alcohol epitheliectomy of the involved cornea, and cryotherapy using a double freeze–slow thaw cycle to the limbus and conjunctival margins. Excision with cryotherapy versus excision alone has been shown to reduce local recurrence rate from 68% to 18%.79 To avoid seeding of tumor cells, it is critical to use fresh instruments after tumor removal. The resulting defect can be closed with amniotic membrane transplantation. Lesions that extend into the globe require enucleation and lesions that extend in the orbit may require exenteration.

Diffuse, multifocal, or recurrent conjunctival melanomas may be more difficult to treat with surgical excision. In these cases, topical chemotherapy using MMC or IFN-α-2b can be used. The majority of the data available is with MMC.80 There are few studies on the use of IFN,81,82 and further studies are needed. For PAM with atypia, topical MMC has similar recurrence rates as reported following local excision and cryotherapy.83

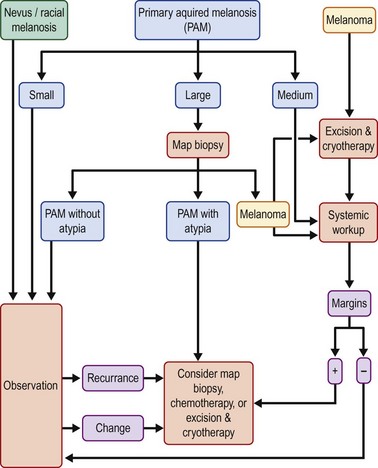

Metastatic disease to the regional lymph nodes may be treated with lymph node dissection and adjuvant therapy in the form of radiation or chemotherapy. Disseminated conjunctival melanoma is treated with systemic chemotherapy combined with interferon.59 Figure 19.12 summarizes the algorithm for the management of pigmented lesions of the conjunctiva.

Prognosis

Local recurrence is common after surgery, with recurrence rates estimated to be as high as 43% to 50% at 10 years.71,84 Any recurrence of tumor, whether pigmented or not, should be surgically excised and treated with cryotherapy. Shields and colleagues found that regional or distant tumor metastasis was present in 16% of patients at 5 years, 26% at 10 years, and 32% at 15 years.71 The most common regional lymph nodes to be involved are the preauricular, submandibular, and deeper cervical lymph nodes. The most common sites of distant metastasis are the brain, liver, and lungs. The 10-year mortality rate has been reported to range from 13% to 30%.71,85 Unfavorable prognosis is associated with non-limbal tumors, the presence of positive tumor margins on pathology, and de novo melanoma.64 Shields and colleagues found that the 10-year mortality rate of tumors with de novo origin (35%) was four times greater than the mortality rate of those with melanoma arising from nevus or PAM (9%).64

Due to the high rate of metastases, patients should be monitored regularly for metastatic disease. Physical examination should include palpation of the lymph nodes of the head and neck. An annual chest X-ray and brain MRI are advised.74

Conjunctival Lymphoma

Conjunctival lymphomas are the third most common conjunctival malignancy after melanoma, accounting for 1.5% of all conjunctival tumors.86 Ocular adnexal lymphoma is most common in the orbit (64%), followed by the conjunctiva (28%), and the eyelids (8%).87 It accounts for 2% of all cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and 8% of all cases of NHL at extranodal sites.88 The average age of presentation for conjunctival lymphoma is in the sixth decade of life.89 Bilateral presentation occurs 20% to 38% of the time and systemic involvement is present in 20% to 31% of cases.90 The majority of ocular adnexal lymphomas are mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, a subtype of extranodal marginal zone lymphomas.

Etiology

The association between gastric MALT lymphoma and H. pylori infection has been well established. Recently, H. pylori has been detected in conjunctival MALT lymphomas as well.91 Although this relationship is not yet well established, further investigation is warranted.

An association between the intracellular bacterium C.psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphoma has also been reported.92,93 This has led to a strong interest in the use of doxycycline in treating ocular adnexal lymphomas, which has been demonstrated with some success.93 Other studies have demonstrated no association with C. psittaci94 or a variable association in different geographic areas.92

Clinical Features

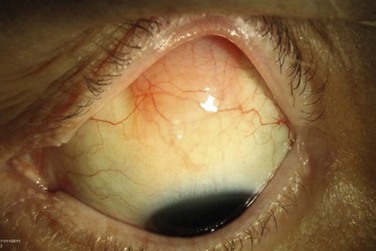

Conjunctival lymphoma can present in one of two ways. Most commonly, it presents as a diffuse, slightly elevated, pink, fleshy mass with the classic description of ‘salmon patch’ (Fig. 19.13). It is most commonly located in the forniceal or midbulbar conjunctiva, hidden under the eyelid in the superior and inferior quadrants.90 It is usually painless with an insidious onset. Less commonly, conjunctival lymphoma presents as a chronic follicular conjunctivitis.

Pathology

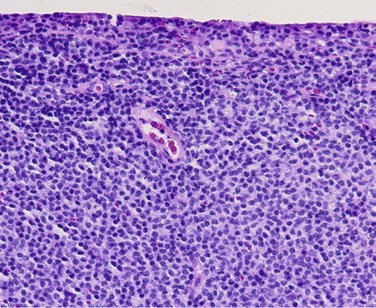

Lymphoid tumors are composed of solid sheets of lymphocytes and may be classified as benign reactive hyperplasia, atypical lymphoid hyperplasia, or malignant lymphoma.27,90 The vast majority of conjunctival lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s B-cell tumors. Two-thirds of tumors are the MALT/EBZL subtype.95 Other histologic subtypes include follicular cell, lymphoplasmacytic, mantle cell, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. MALT, follicular cell, and lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas are low-grade tumors with an indolent course, while mantle cell and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are considered high-grade tumors with an aggressive course.96

Under light microscopy, MALT lymphoma demonstrates a diffuse cellular infiltrate composed of small round lymphocytes, atypical lymphocytes with cleaved nuclei, monocytoid cells, and plasma cells (Fig. 19.14). Neoplastic cells expand the margin zone and may proliferate within germinal centers, creating numerous poorly formed secondary follicles.97 Follicular cell lymphoma demonstrates well-formed follicles with a germinal center arrangement.

Immunophenotypic analysis and flow cytometry can provide information regarding cell population type by identifying markers, such as the CD20 antigen on B cells. Molecular genetic analysis can be useful in identifying overexpression of heavy rearrangements, as well as translocations specific to tumor types.96 The genetic analysis is critical for differentiating a monoclonal versus benign polyclonal population.

Treatment

When localized to the conjunctiva, the standard of treatment is external beam radiation. Radiotherapy has been proven to be effective for all different subtypes of conjunctival lymphoma, with local control rates ranging from 91% to 100%.89 Recommended radiation doses are approximately 30–40 Gy, with the dosage based on tumor grade or type.98 The major adverse effects of radiation include dry eye, conjunctivitis, cataract, and radiation retinopathy.

Surgical excision with cryotherapy for localized disease can be considered when lesions are small and circumscribed.90 Intralesional injections of interferon α-2b have been reported with success.99 In a recent interventional pilot study of three patients with relapsed conjunctival lymphoma, Ferreri and colleagues demonstrated disease remission after intralesional rituximab injections for localized disease.100

When systemic involvement is present, first-line treatment is typically rituximab alone or in combination with chemotherapy. Rituximab is a recombinant mouse/human chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, that is being investigated as a first-line treatment of CD20-positive lymphomas with systemic involvement. By binding the CD20 antigen on B cells, rituximab triggers apoptosis and antibody-mediated cytotoxicity. Salepci et al. reported a case of bilateral conjunctival MALT lymphoma, which relapsed after radiation treatment. Remission was achieved with six weekly cycles on intravenous rituximab.101 Ferreri and colleagues demonstrated lymphoma regression in five patients with newly diagnosed ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma treated with intravenous rituximab as a single agent. However, four of five patients demonstrated relapse at a median time of 5 months, suggesting a lower efficacy than reported for gastric MALT lymphoma.102

Rituximab in combination with chemotherapy may achieve greater success. In a study of nine patients with newly diagnosed ocular adnexal lymphomas, first-line therapy with rituximab and chlorambucil achieved complete remission in 89% of patients, with a median follow-up of 2 years.103 The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group is currently conducting a multicenter trial to determine whether the addition of rituximab to chlorambucil will improve the outcome of MALT lymphoma in comparison to treatment with chlorambucil or rituximab alone.104

Another agent being investigated in the treatment of systemic lymphomas is ibritumomab tiuxetan (trade name ZevalinTM). Zevalin is a combination of a mouse Ig1 monoclonal antibody with the chelator tiuxetan, to which the radioactive isotope yttrium-90 is added. It binds to the C20 antigen of B cells and the radiation from the isotope kills cells. Zevalin was FDA approved in 2002, to treat patients with relapsed or refractory, low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In a pilot study of 12 patients with ocular adnexal lymphoma, treated with rituximab followed by Zevalin, 83% of patients achieved a complete response, with no evidence of recurrence at median follow-up time of 20 months.105 Adverse effects included pancytopenia, fatigue, nausea, and headache. The most serious adverse effect is the increased incidence of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia, as a recent study showed a 5-year cumulative incidence of 8.29% of these cancers after treatment with Zevalin.106

Due to the association between C. psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas, doxycycline has emerged as a promising management option. In a multicenter prospective trial of 27 patients with untreated or relapsed ocular adnexal MALT, Ferreri and colleagues investigated the effect of 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily for 3 weeks on lymphoma remission. Doxycycline treatment produced an overall response rate of 48% among the entire patient population, and a 64% response rate in those with ocular adnexal lymphomas positive for Cp DNA. At 2 years, 67% of those with Cp DNA-positive lymphomas had no evidence of recurrence. In addition, doxycycline eliminated C. psittaci infection in all patients with positive Cp DNA. The International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has initiated a large international prospective trial to investigate the effect of the doxycycline.107 The major advantage of doxycycline treatment is that it is relatively safe and inexpensive.

Prognosis

Conjunctival lymphoma has the best prognosis of the ocular adnexal lymphomas, with systemic lymphoma developing in only 20% to 31% of patients. In lymphomas of the orbit and eyelid, systemic involvement is present in 35% and 70%, respectively.90 Since systemic involvement can occur up to several years after ocular diagnosis, patients should be monitored for systemic involvement every 6 months for 5 years and yearly thereafter.

The prognosis is best for MALT lymphomas compared with follicular, diffuse large B-cell, mantle cell and lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas. Spontaneous regression of MALT lymphomas 1 to 5 years following biopsy has been reported.108

Miscallenous Tumors

Prior to the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) was one of the most common acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related illnesses.109 It is a vascular tumor that most commonly affects the skin, but can also involve the mucous membranes and internal organs. Conjunctival and adnexal KS were among the first ocular lesions described in individuals with AIDS and can be an AIDS-defining illness.110

In 1995, Chang and colleagues identified a new herpes virus in KS lesions from patients with AIDS, now known as the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8).111 HHV-8 is found in 95% of patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma and is thought to be important in the pathogenesis of KS. 112

Although most commonly presenting as an eyelid tumor, KS can also develop in the conjunctiva. Conjunctival KS is most commonly seen in the lower fornix, followed by the bulbar conjunctiva and the upper fornix.113 Clinically, it appears as a painless, reddish vascular mass that may resemble a hemorrhagic conjunctivitis.

Pathology demonstrates malignant spindle-shaped cells with elongated oval nuclei surrounding a complex arrangement of capillary channels and vascular spaces without endothelium.113

Conjunctival KS typically has an indolent course, with the goal of treatment being palliation of symptoms and preservation of vision.114 If small, circumscribed, and localized to the bulbar conjunctiva, surgical excision may be performed.

KS tumors are radiosensitive and local radiation can produce palliation of symptoms.115 Intralesional α-2b has also been reported to be effective in case reports.116 Systemic treatment includes chemotherapy and immune reconstitution with highly active antiretroviral therapy.113

Conjunctival Metastatic Tumors

Metastatic tumors to the conjunctiva are rare. In a report of 1643 tumors of the conjunctiva, 13 cases of conjunctival metastasis were described.5 The most commonly reported primary cancers associated with metastasis are breast, lung, and cutaneous melanoma. Laryngeal cancer has also been reported.68 Rarely, bilateral conjunctival infiltrates may be the first sign of relapsed acute leukemia.117

Most patients presenting with conjunctival metastasis have a previously diagnosed primary malignancy, as conjunctival metastasis occurs at advanced stages of disease. Occasionally, it may be the first presenting sign of an underlying systemic cancer that has not yet been diagnosed.118 The mean survival time after diagnosis of conjunctival metastasis is on the order of months.68

Sebaceous Cell Carcinoma

Sebaceous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm arising from meibomian glands, Zeiss glands, or the sebaceous glands of caruncle. It accounts for 1–5.5% of all eyelid malignancies, occurring typically between the ages of 60 to 70.119

The conjunctival epithelium can be secondarily involved in 40% to 80% of cases by pagetoid (intraepithelial) spread. When there is diffuse intraepithelial involvement of the bulbar, forniceal, or tarsal conjunctiva, sebaceous cell carcinoma can mimic a chronic unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis. In rare cases, it may arise within the conjunctival epithelium, without any underlying glandular carcinoma.31

The most common site of metastasis is the regional lymph nodes, reported in 8% to 14% of cases.120 Increased awareness, leading to earlier detection and treatment has improved mortality rates from 24% in the past to less than 10%.120

Secondary Conjunctival Involvement from Adjacent Tumors

The conjunctiva may be involved by extraocular extension of intraocular tumors and by extension of eyelid and orbital tumors. Extrascleral extension of a ciliary body melanoma into subconjunctival tissue can simulate a conjunctival melanoma.28 Rhabdomyosarcoma of the orbit, the most common orbital malignancy of childhood, can also demonstrate extension into subconjunctival tissue from the anterior orbit and thus, can present as a conjunctival mass.121 It can also rarely present localized to the conjunctiva without orbital involvement.122

References

1. Lee, GA, Hirst, LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:429–450.

2. Sun, EC, Fears, TR, Goedert, JJ. Epidemiology of squamous cell conjunctival cancer. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:73–77.

3. Lee, GA, Hirst, LW. Incidence of ocular surface epithelial dysplasia in metropolitan Brisbane. A 10-year survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:525–527.

4. Ateenyi-Agaba, C. Conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, Uganda. Lancet. 1995;345:695–696.

5. Shields, CL, Demirci, H, Karatza, E, et al. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1747–1754.

6. Gaasterland, DE, Rodrigues, MM, Moshell, AN. Ocular involvement in xeroderma pigmentosum. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:980–986.

7. Karp, CL, Scott, IU, Chang, TS, et al. Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. A possible marker for human immunodeficiency virus infection? Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:257–261.

8. Lee, GA, Williams, G, Hirst, LW, et al. Risk factors in the development of ocular surface epithelial dysplasia. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:360–364.

9. Newton, R, Ferlay, J, Reeves, G, et al. Effect of ambient solar ultraviolet radiation on incidence of squamous-cell carcinoma of the eye. Lancet. 1996;347:1450–1451.

10. Trosko, JE, Krause, D, Isoun, M. Sunlight-induced pyrimidine dimers in human cells in vitro. Nature. 1970;228:358–359.

11. Dushku, N, Hatcher, SL, Albert, DM, et al. p53 expression and relation to human papillomavirus infection in pingueculae, pterygia, and limbal tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1593–1599.

12. Spitzer, MS, Batumba, NH, Chirambo, T, et al. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia as the first apparent manifestation of HIV infection in. Malawi. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:422–425.

13. McDonnell, JM, McDonnell, PJ, Sun, YY. Human papillomavirus DNA in tissues and ocular surface swabs of patients with conjunctival epithelial neoplasia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:184–189.

14. Scott, IU, Karp, CL, Nuovo, GJ. Human papillomavirus 16 and 18 expression in conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:542–547.

15. Eng, HL, Lin, TM, Chen, SY, et al. Failure to detect human papillomavirus DNA in malignant epithelial neoplasms of conjunctiva by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:429–436.

16. Guthoff, R, Marx, A, Stroebel, P. No evidence for a pathogenic role of human papillomavirus infection in ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Germany. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:666–671.

17. Basti, S, Macsai, MS. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a review. Cornea. 2003;22:687–704.

18. McDonnell, JM, Wagner, D, Ng, ST, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in ocular and cervical swabs of women with genital tract condylomata. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:61–66.

19. Kiire, CA, Srinivasan, S, Karp, CL. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:35–46.

20. Napora, C, Cohen, EJ, Genvert, GI, et al. Factors associated with conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: a case control study. Ophthalm Surg. 1990;21:27–30.

21. Pe’er, J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ophthalmol Clin N Am. 2005;18:1–13. [vii].

22. Degrassi, M, Piantanida, A, Nucci, P. Unexpected histological findings in pterygium. Optometry and Vision Science. 1993;70:1058–1060.

23. Shields, CL, Ramasubramanian, A, Mellen, PL, et al. Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma arising in immunosuppressed patients (organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus infection). Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2133–2137. [e1].

24. Farah, S, Baum, TD, Conlon, R, et al. Tumors of the cornea and conjunctiva. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, eds. Principles and practice of ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 2000:1002–1019.

25. Warner, MA, Mehta, MN, Jakobiec, FA. Squamous neoplasms of the conjunctiva. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby; 2005:461–475.

26. Pe’er, J, Frucht-Pery, J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. In: Singh AD, ed. Clinical ophthalmalmic oncology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:136–140.

27. Shields, JA, Shields, CL. Eyelid, conjunctival, and orbital tumors : an atlas and textbook, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [p. xiii, 805].

28. Shields, CL, Shields, JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:3–24.

29. Rudkin, AK, Dodd, T, Muecke, JS. The differential diagnosis of localised amelanotic limbal lesions: a review of 162 consecutive excisions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:350–354.

30. Hirst, LW, Axelsen, RA, Schwab, I. Pterygium and associated ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:31–32.

31. Margo, CE, Grossniklaus, HE. Intraepithelial sebaceous neoplasia without underlying invasive carcinoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:293–301.

32. Gelender, H, Forster, RK. Papanicolaou cytology in the diagnosis and management of external ocular tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:909–912.

33. Larmande, A, Timsit, E. Importance of cytodiagnosis in ophthalmology: preliminary report of 8 cases of tumors of the sclero-corneal limbus. Bulletin des sociétés d’ophtalmologie de France. 1954;5:415–419.

34. Nolan, GR, Hirst, LW. Impression cytology in the diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:888.

35. Malandrini, A, Martone, G, Traversi, C, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy in a patient with recurrent conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86:690–691.

36. Duchateau, N, Hugol, D, D’Hermies, F, et al. Contribution of in vivo confocal microscopy to limbal tumor evaluation. Journal français d’ophtalmologie. 2005;28:810–816.

37. Kieval, JZ, Karp, CL, Shousha, MA, et al. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography for differentiation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2011;119:481–486.

38. Shields, JA, Shields, CL, De Potter, P. Surgical management of conjunctival tumors. The 1994 Lynn B. McMahan Lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:808–815.

39. Peksayar, G, Soyturk, MK, Demiryont, M. Long-term results of cryotherapy on malignant epithelial tumors of the conjunctiva. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:337–340.

40. Gündüz, K, Uçakhan, OO, Kanpolat, A, et al. Nonpreserved human amniotic membrane transplantation for conjunctival reconstruction after excision of extensive ocular surface neoplasia. Eye. 2006;20:351–357.

41. Espana, EM, Prabhasawat, P, Grueterich, M, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation for reconstruction after excision of large ocular surface neoplasias. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:640–645.

42. Hick, S, Demers, PE, Brunette, I, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation and fibrin glue in the management of corneal ulcers and perforations: a review of 33 cases. Cornea. 2005;24:369–377.

43. Prabhasawat, P, Tarinvorakup, P, Tesavibul, N, et al. Topical 0.002% mitomycin C for the treatment of conjunctival-corneal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Cornea. 2005;24:443–448.

44. Sepulveda, R, Pe’er, J, Midena, E, et al. Topical chemotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: current status. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:532–535.

45. Yeatts, RP, Engelbrecht, NE, Curry, CD, et al. 5-Fluorouracil for the treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia of the conjunctiva and cornea. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2190–2195.

46. Midena, E, Angeli, CD, Valenti, M, et al. Treatment of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma with topical 5-fluorouracil. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:268–272.

47. Chakalova, G, Ganchev, G. Local administration of interferon-alpha in cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia associated with human papillomavirus infection. Journal of B.U.ON. 2004;9:399–402.

48. Edwards, L, Berman, B, Rapini, RP, et al. Treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas by intralesional interferon alfa-2b therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:1486–1489.

49. Decatris, M, Santhanam, S, O’Byrne, K. Potential of interferon-alpha in solid tumours: part 1. BioDrugs. 2002;16:261–281.

50. Bergman, SJ, Ferguson, MC, Santanello, C. Interferons as therapeutic agents for infectious diseases. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2011;25:819–834.

51. Galor, A, Karp, CL, Chhabra, S, et al. Topical interferon alpha 2b eye-drops for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a dose comparison study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:551–554.

52. Karp, CL, Galor, A, Chhabra, S, et al. Subconjunctival/perilesional recombinant interferon alpha-2b for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a 10-year review. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2241–2246.

53. Karp, CL, Moore, JK, Rosa, RH, Jr. Treatment of conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia with topical interferon alpha-2b. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1093–1098.

54. Stokes, JJ. Intraocular extension of epibulbar squamous cell carcinoma of the limbus. Transactions – American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1955;59:143–146.

55. Tabbara, KF, Kersten, R, Daouk, N, et al. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:318–321.

56. Shields, CL, Fasiuddin, AF, Mashayekhi, A, et al. Conjunctival nevi: clinical features and natural course in 410 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:167–175.

57. Shields, JA, Shields, CL, Mashayekhi, A, et al. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva: risks for progression to melanoma in 311 eyes. The 2006 Lorenz E. Zimmerman lecture. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:511–519. [e2].

58. Folberg, R, McLean, IW, Zimmerman, LE. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:129–135.

59. Seregard, S. Conjunctival melanoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:321–350.

60. Hu, DN, Yu, G, McCormick, SA, et al. Population-based incidence of conjunctival melanoma in various races and ethnic groups and comparison with other melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:418–423.

61. Triay, E, Bergman, L, Nilsson, B, et al. Time trends in the incidence of conjunctival melanoma in Sweden. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1524–1528.

62. Yu, GP, Hu, DN, McCormick, S, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: is it increasing in the United States? Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:800–806.

63. Tuomaala, S, Eskelin, S, Tarkkanen, A, et al. Population-based assessment of clinical characteristics predicting outcome of conjunctival melanoma in whites. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3399–3408.

64. Shields, CL, Markowitz, JS, Belinsky, I, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: outcomes based on tumor origin in 382 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:389–395. [e1–e2].

65. Singh, AD, De Potter, P, Fijal, BA, et al. Lifetime prevalence of uveal melanoma in white patients with oculo(dermal) melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:195–198.

66. Folberg, R, Jakobiec, FA, Bernardino, VB, et al. Benign conjunctival melanocytic lesions. Clinicopathologic features. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:436–461.

67. Char, DH. Surgical management of melanocytoma of the ciliary body with extrascleral extension. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:404–405.

68. Kiratli, H, Shields, CL, Shields, JA, et al. Metastatic tumours to the conjunctiva: report of 10 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:5–8.

69. Brownstein, S. Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva. Cancer Control. 2004;11:310–316.

70. Pe’er, J, Folberg, R. Conjunctival melanoma. In: Singh AD, Damato BE, Pe’er J, et al, eds. Clinical ophthalmic oncology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

71. Shields, CL, Shields, JA, Gunduz, K, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1497–1507.

72. Ho, VH, Prager, TC, Diwan, H, et al. Ultrasound biomicroscopy for estimation of tumor thickness for conjunctival melanoma. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35:533–537.

73. Shields, CL, Belinsky, I, Romanelli-Gobbi, M, et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography of conjunctival nevus. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:915–919.

74. Shields, CL, Shields, JA. Ocular melanoma: relatively rare but requiring respect. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27:122–133.

75. Tuomaala, S, Kivela, T. Metastatic pattern and survival in disseminated conjunctival melanoma: implications for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:816–821.

76. Jakobiec, FA, Folberg, R, Iwamoto, T. Clinicopathologic characteristics of premalignant and malignant melanocytic lesions of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:147–166.

77. Folberg, R, McLean, IW. Primary acquired melanosis and melanoma of the conjunctiva: terminology, classification, and biologic behavior. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:652–654.

78. Iwamoto, S, Burrows, RC, Grossniklaus, HE, et al. Immunophenotype of conjunctival melanomas: comparisons with uveal and cutaneous melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1625–1629.

79. De Potter, P, Shields, CL, Shields, JA, et al. Clinical predictive factors for development of recurrence and metastasis in conjunctival melanoma: a review of 68 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:624–630.

80. Kurli, M, Finger, PT. Topical mitomycin chemotherapy for conjunctival malignant melanoma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia: 12 years’ experience. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:1108–1114.

81. Finger, PT, Sedeek, RW, Chin, KJ. Topical interferon alfa in the treatment of conjunctival melanoma and primary acquired melanosis complex. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:124–129.

82. Herold, TR, Hintschich, C. Interferon alpha for the treatment of melanocytic conjunctival lesions. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:111–115.

83. Pe’er, J, Frucht-Pery, J. The treatment of primary acquired melanosis (PAM) with atypia by topical Mitomycin C. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:229–234.

84. Norregaard, JC, Gerner, N, Jensen, OA, et al. Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva: occurrence and survival following surgery and radiotherapy in a Danish population. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:569–572.

85. Seregard, S, Kock, E. Conjunctival malignant melanoma in Sweden 1969–91. Acta Ophthalmologica. 1992;70:289–296.

86. Grossniklaus, HE, Green, WR, Luckenbach, M, et al. Conjunctival lesions in adults. A clinical and histopathologic review. Cornea. 1987;6:78–116.

87. Knowles, DM, Jakobiec, FA, McNally, L, et al. Lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma occurring in the ocular adnexa (orbit, conjunctiva, and eyelids): a prospective multiparametric analysis of 108 cases during 1977 to 1987. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:959–973.

88. Bairey, O, Kremer, I, Rakowsky, E, et al. Orbital and adnexal involvement in systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1994;73:2395–2399.

89. Tsai, PS, Colby, KA. Treatment of conjunctival lymphomas. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20:239–246.

90. Shields, CL, Shields, JA, Carvalho, C, et al. Conjunctival lymphoid tumors: clinical analysis of 117 cases and relationship to systemic lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:979–984.

91. Lee, SB, Yang, JW, Kim, CS. The association between conjunctival MALT lymphoma and Helicobacter pylori. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:534–536.

92. Chanudet, E, Zhou, Y, Bacon, CM, et al. Chlamydia psittaci is variably associated with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in different geographical regions. J Pathol. 2006;209:344–351.

93. Ferreri, AJ, Ponzoni, M, Guidoboni, M, et al. Bacteria-eradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a multicenter prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1375–1382.

94. Rosado, MF, Byrne, Jr, GE., Ding, F, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107:467–472.

95. Auw-Haedrich, C, Coupland, SE, Kapp, A, et al. Long term outcome of ocular adnexal lymphoma subtyped according to the REAL classification. Revised European and American Lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:63–69.

96. Bardenstein, DS. Orbital and adnexal lymphoma. In: Singh AD, Damato BE, Pe’er J, et al, eds. Clinical ophthalmic oncology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

97. Cahill, M, Barnes, C, Moriarty, P, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma-comparison of MALT lymphoma with other histological types. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:742–747.

98. Martinet, S, Ozsahin, M, Belkacemi, Y, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in orbital lymphoma: a Rare Cancer Network study on 90 consecutive patients treated with radiotherapy. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:892–898.

99. Blasi, MA, Tiberti, AC, Valente, P, et al. Intralesional interferon-alpha for conjunctival mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma long-term results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:494–500.

100. Ferreri, AJ, Govi, S, Colucci, A, et al. Intralesional rituximab: a new therapeutic approach for patients with conjunctival lymphomas. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:24–28.

101. Salepci, T, Seker, M, Kurnaz, E, et al. Conjunctival malt lymphoma successfully treated with single agent rituximab therapy. Leukemia Res. 33, 2009.

102. Ferreri, AJ, Ponzoni, M, Martinelli, G, et al. Rituximab in patients with mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Haematologica. 2005;90:1578–1579.

103. Rigacci, L, Nassi, L, Puccioni, M, et al. Rituximab and chlorambucil as first-line treatment for low-grade ocular adnexal lymphomas. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:565–568.

104. International Exranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Multicenter randomized trial of chlorambucil versus chlorambucil plus rituximab versus rituximab in extranodal marginal zone b-cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT Lymphoma). Available from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00210353.

105. Esmaeli, B, McLaughlin, P, Pro, B, et al. Prospective trial of targeted radioimmunotherapy with Y-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) for front-line treatment of early-stage extranodal indolent ocular adnexal lymphoma. Annals of. Oncology. 2009;20:709–714.

106. Guidetti, A, Carlo-Stella, C, Ruella, M, et al. Myeloablative doses of yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan and the risk of secondary myelodysplasia/acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:5074–5084.

107. International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. A clinico-pathological study to investigate the possible infective causes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the ocular adnexae. Available from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01010295.

108. Matsuo, T, Yoshino, T. Long-term follow-up results of observation or radiation for conjunctival malignant lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1233–1237.

109. Dal Maso, L, Serraino, D, Franceschi, S. Epidemiology of AIDS-related tumours in developed and developing countries. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1188–1201.

110. Holland, GN, Gottlieb, MS, Yee, RD, et al. Ocular disorders associated with a new severe acquired cellular immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:393–402.

111. Chang, Y, Cesarman, E, Pessin, MS, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869.

112. Moore, PS, Chang, Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1181–1185.

113. Jeng, BH, Holland, GN, Lowder, CY, et al. Anterior segment and external ocular disorders associated with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:329–368.

114. Kohanim, S, Daniels, AB, Huynh, N, et al. Local treatment of Kaposi sarcoma of the conjunctiva. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2011;51:183–192.

115. Ghabrial, R, Quivey, JM, Dunn, Jr, JP., et al. Radiation therapy of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi’s sarcoma of the eyelids and conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:1423–1426.

116. Qureshi, YA, Karp, CL, Dubovy, SR. Intralesional interferon alpha-2b therapy for adnexal Kaposi sarcoma. Cornea. 2009;28:941–943.

117. Font, RL, Mackay, B, Tang, R. Acute monocytic leukemia recurring as bilateral perilimbal infiltrates. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural confirmation. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1681–1685.

118. Shields, JA, Gunduz, K, Shields, CL, et al. Conjunctival metastasis as the initial manifestation of lung cancer. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:399–400.

119. Kass, LG, Hornblass, A. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular adnexa. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;33:477–490.

120. Shields, JA, Demirci, H, Marr, BP, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2151–2157.

121. Shields, JA, Shields, CL. Rhabdomyosarcoma: review for the ophthalmologist. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:39–57.

122. Joffe, L, Shields, JA, Pearah, JD. Epibulbar rhabdomyosarcoma without proptosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1977;14:364–367.