Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an increasingly common treatment for hematologic, immunologic, metabolic and neoplastic diseases. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a complication of allogeneic HSCT where an immunologic response by donor cells against host tissues occurs due to incompatibility between the recipient and donor cells. The prevalence of GVHD varies between 10% and 90% depending on age, donor cell compatibility, host environment, and prophylaxis protocols.1,2 Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers are the most important factors, triggering the immune response and leading to the onset of GVHD. Tissues most commonly targeted by donor cells include, the gastrointestinal system, liver, lungs, skin and eyes.

Clinical Manifestations

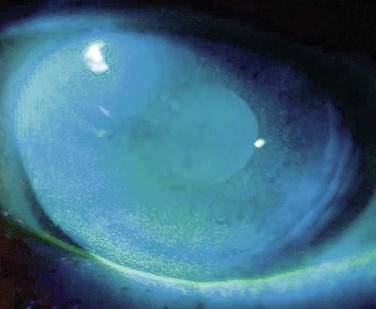

Ocular GVHD affects 60–90% of patients with chronic systemic GVHD and may be the initial presentation of systemic GVHD.3,4 Ocular manifestations vary widely from mild findings, to severe ocular sequelae and can affect the eyelid, lacrimal gland, conjunctiva, tear film, cornea, lens, vitreous, retina and optic nerve.3,5–7 The most common presentation includes diseases of the ocular surface and lacrimal gland, with symptoms of dryness, irritation, blurred vision, photophobia, redness, and mucous discharge. Dry eye syndrome (DES) or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) occurs in 70% of GVHD patients. Patients, especially those with severe disease, frequently demonstrate conjunctival edema, chemosis, and pseudomembrane formation. Disease progression may lead to punctate keratopathy, corneal epithelial erosions, and corneal infections and ulcerations (Fig. 23.1). In addition to keratoconjunctivitis sicca, frequent manifestations of ocular GVHD include, conjunctival inflammation and fibrosis, cicatricial lagophthalmos, sterile conjunctivitis and uveitis.6,8 It may also manifest with lacrimal gland dysfunction, spontaneous lacrimal punctual occlusion (SLPO), cicatricial ectropion or entropion, trichiasis, meibomian gland dysfunction, calcareous corneal degeneration, corneal perforation, synechiae, cataract, retinal vasculitis, retinal hemorrhage and optic neuropathy.5–7,9–12 Ocular GVHD can have clinical manifestations similar to those of autoimmune and collagen vascular diseases affecting the eye, but ocular GVHD does not typically affect the posterior chamber.

Pathophysiology

Conjunctivitis is commonly observed as a localized ocular reaction in GVHD. Although the mechanism is not fully understood, flow cytometry has demonstrated the proliferation of T cells in subconjunctival immunogenic inflammation.13 Histopathology has revealed lymphocyte exocytosis and satellitosis, dyskeratotic cells, epithelial cell necrosis, subepithelial microvesicle formation and eventually, total separation of the epithelium in the conjunctiva of patients with GVHD.6,14 Epithelial attenuation and goblet cell depletion have also been observed.9

In GVHD, donor lymphocytes infiltrate the lacrimal gland, leading to widespread fibrosis and aqueous tear deficiency.15 Histopathology of the lacrimal gland in patients with chronic GVHD and DES reveals PAS-positive material accumulation in the acini and ductules, predominant T-cell infiltration in periductal areas, increased number and activation of stromal fibroblasts and excessive extracellular matrix fibrosis.16 There is also prominent fibrosis of the glandular interstitium, similar to the chronic skin GVHD changes with generalized sclerodermal lichenoid.9 Postmortem autopsy studies of the lacrimal gland in patients with GVHD have shown stasis of lacrimal gland secretions, epithelial cell debris within the lumina of lacrimal glands and periductal inflammation and fibrosis.15 Additionally, immunohistochemical studies show primarily CD4 and CD8 T-cell infiltration in periductal areas of lacrimal glands of patients with chronic GVHD.15

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) can also lead to dry eye symptoms in patients with GVHD. The meibomian glands secrete the lipid component of the tear film in order to retard tear evaporation. A recent study reported that 63% of chronic GVHD patients had MGD, with significant correlation in severity of DES symptoms.6

Diagnosis

A thorough patient history and ocular examination are necessary for the clinical diagnosis of ocular GVHD. Essential components of the history include extent of systemic GVHD, as well as systemic medications. The diagnostic criteria for ocular GVHD were established by the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease in 2005. The Diagnosis and Staging Working Group has stated that a mean Schirmer value of 5 mm at 5 minutes or new onset of keratoconjunctivitis sicca by slit lamp examination, with a mean Schirmer value of 6–10 mm, is sufficient for the diagnosis of chronic GVHD, if accompanied by involvement of at least one other organ system.17

Conjunctival biopsy may also aid in the diagnosis of ocular GVHD. Histopathology may reveal lymphocyte exocytosis and satellitosis, dyskeratotic cells, epithelial cell necrosis, subepithelial microvesicle formation and eventual total separation of the epithelium in the conjunctiva of patients with GVHD.6,14

Classification

Multiple classification systems have been used to categorize ocular GVHD. In 1989, Jabs et al. proposed a clinical staging system for conjunctival involvement in ocular GVHD (Table 23.1).14 In 1998, Kiang et al. characterized the course of ocular GVHD into four stages (Table 23.2).18

Table 23.1

Clinical Staging System for Conjunctivitis in Ocular GVHD

| Stage I | Hyperemia |

| Stage II | Hyperemia with chemosis and/or serosanguineous exudates |

| Stage III | Pseudomembranous/membranous conjunctivitis |

(Adapted from Jabs DA, Wingard J, Green WR, et al. The eye in bone marrow transplantation. III. Conjunctival graft-vs-host disease. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:1343–8.)

Table 23.2

| Stage 1 | Subclinical stage | Tearing, mild nonspecific discomfort and photophobia. Mild chemosis, possible rose bengal staining. Lasting from a few days up to 1 month before other systemic symptoms of GVHD occur or the patient progresses to a more severe form of ocular GVHD. |

| Stage 2 | Active stage | Mucopurulent conjunctivitis, pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, punctate keratitis or corneal abrasion. Patients usually have systemic manifestations of GVHD. |

| Stage 3 | Convalescent stage | Secondary sicca. Irregular eyelid margins with obstructed meibomian gland orifices, tarsal and forniceal scarring and punctate corneal epitheliopathy |

| Stage 4 | Necrotizing stage | Corneal melting and possible corneal perforation. |

(Adapted from Kiang E, Tesavibul N, Yee R, et al. The Use of Topical Cyclosporine A in Ocular Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Bone Marrow Transplantation 1998;22:147–51.)

An alternative classification system was proposed by Robinson et al. in 2004.19 In this system, clinically relevant grading criteria for conjunctival GVHD are based on conjunctival pathology, observed in chronic GVHD patients (Table 23.3).

Table 23.3

Clinical Grading Criteria For Conjunctival GVHD

| Grade 1 | Conjunctival hyperemia occurring on the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva in at least one eyelid |

| Grade 2 | Palpebral conjunctival fibrovascular changes occurring along the superior border of the upper eyelid, or the lower border of the tarsal plate of the lower eyelid, with or without conjunctival epithelial sloughing, involving < 25% of the total surface area in at least one eyelid |

| Grade 3 | Palpebral conjunctival fibrovascular changes occurring along the superior border of the upper eyelid, or the lower border of the tarsal plate of the lower eyelid, involving 25–75% of the total surface area in at least one eyelid |

| Grade 4 | Palpebral conjunctival fibrovascular changes involving > 75% of the total surface area with or without a cicatricial entropion in at least one eyelid |

(Adapted from Robinson MR, Lee SS, Rubin BI, et al. Topical Corticosteroid Therapy for Cicatricial Conjunctivitis Associated with Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Bone Marrow Transplantation 2004;33:1031–5.)

Management

Prevention

Prevention of disease plays an important role in decreasing the morbidity associated with ocular GVHD. Environmental modifications and decreased exposure to low-humidity settings may reduce DES symptoms. Cool mist humidifiers can be particularly helpful for environmental modifications at home, including bedside use while sleeping. Minimizing ultraviolet light exposure and regular surveillance with ophthalmologic evaluation, can monitor for the development of infection, cataract, and intraocular pressure elevation. Therefore, a thorough ocular examination is recommended prior to HSCT. Prophylactic use of topical cyclosporine 0.05% might also reduce severity of disease.20

Local Medical Treatment

Lubrication and Reduction of Tear Evaporation

Preservative-free artificial tears and ophthalmic lubricating ointments are effective approaches in providing lubrication and diluting inflammatory mediators in the tear film.2,21 Punctal occlusion can effectively decrease tear drainage from the ocular surface, with either silicone plugs or permanent thermal cauterization. Moisture chamber goggles may also prove beneficial in reducing tear evaporation and increasing patient comfort.

Topical Cyclosporine A

Topical cyclosporine A is an anti-inflammatory agent, which produces local inhibition of T lymphocytes and cytokine production in the conjunctiva. As a result, cyclosporine can minimize destruction of lacrimal gland tissue and reduce keratitis sicca. Numerous studies have reported improvement in dry eye symptoms, corneal sensitivity, tear evaporation rate, tear break-up time, vital staining scores, goblet cell density, conjunctival squamous metaplasia grade and inflammatory cell numbers after treatment with topical cyclosporine 0.05%.20,22–24 This has been used primarily in patients of chronic GVHD and KCS with minimal improvement, despite lubrication and topical steroids.

Autologous Serum Eye Drops

Autologous serum tears 20–50% have been used safely and effectively in the treatment of DES in patients with ocular GVHD. Unlike artificial tears, they contain albumin, epidermal growth factor, fibronectin, vitamin A, neurotrophic growth factor, and hepatocyte growth factor, all of which can assist in maintaining a healthy and stable tear film. Preliminary studies suggest that autologous serum acts to suppress apoptosis in both corneal and conjunctival epithelium.25 A potential concern with this treatment modality is the risk of contamination, leading to infection.

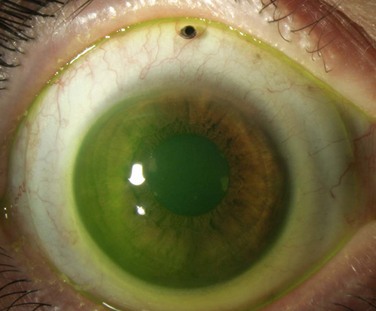

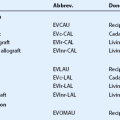

Contact Lenses

Scleral contact lenses have also been used with success in patients with severe or refractory dry eye disease. These larger contact lenses function to create a tear-filled vault on the corneal surface without corneal contact. These include Jupiter lenses, as well as the custom-designed PROSE (Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem) lenses from the Boston Foundation for Sight (Fig. 23.2). Studies have demonstrated improvement in both subjective symptoms and quality of life measures.26

References

1. Ferrara, JL, Levine, JE, Reddy, P, et al. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561.

2. Ferrara, J, Antin, J. The pathophysiology of graft-versus-host disease. In: Forman SJ, ed. Hematopoietic cell transplantation. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999:305–315.

3. Kim, SK. Update on ocular graft versus host disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:344–348.

4. Couriel, D, Carpenter, PA, Cutler, C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:375–396.

5. Mencucci, R, Rossi Ferrini, C, Bosi, A, et al. Ophthalmological aspects in allogenic bone marrow transplantation: Sjögren-like syndrome in graft-versus-host disease. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7:13–18.

6. Ogawa, Y, Okamoto, S, Wakui, M, et al. Dry eye after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1125–1130.

7. Franklin, RM, Kenyon, KR, Tutschka, PJ, et al. Ocular manifestations of graft-vs-host disease. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:4–13.

8. Ratanatharathorn, V, Ayash, L, Lazarus, HM, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: clinical manifestation and therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:121–129.

9. Krachmer, JH. Cornea, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2011.

10. Deeg, HJ. Graft-versus-host disease and the development of late complications. Transfus Sci. 1994;15:243–254.

11. Lavid, FJ, Herreras, JM, Calonge, M, et al. Calcareous corneal degeneration: report of two cases. Cornea. 1995;14:97–102.

12. Kamoi, M, Ogawa, Y, Dogru, M, et al. Spontaneous lacrimal punctal occlusion associated with ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:837–842.

13. Cousins, SW, Streilein, JW. Flow cytometry detection of lymphocyte proliferation in eyes with immunogenic inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2111–2122.

14. Jabs, DA, Wingard, J, Green, WR, et al. The eye in bone marrow transplantation. III. Conjunctival graft-vs-host disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1343–1348.

15. Ogawa, Y, Kuwana, M. Dry eye as a major complication associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cornea. 2003;22:S19–S27.

16. Balaram, M, Rashid, S, Dana, R. Chronic ocular surface disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Ocul Surf. 2005;3:203–211.

17. Filipovich, AH, Weisdorf, D, Pavletic, S, et al. Diagnosis and scoring of chronic graft-versus-host disease. NIH consensus development conference on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956.

18. Kiang, E, Tesavibul, N, Yee, R, et al. The use of topical cyclosporine A in ocular graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:147–151.

19. Robinson, MR, Lee, SS, Rubin, BI, et al. Topical corticosteroid therapy for cicatricial conjunctivitis associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:1031–1035.

20. Malta, JB, Soong, HK, Shtein, RM, et al. Treatment of ocular graft-versus-host disease with topical cyclosporine 0.05%. Cornea. 2010;29:1392–1396.

21. Kim, SK, Couriel, D, Ghosh, S, et al. Ocular graft vs. host disease experience from MD Anderson Cancer Center: Newly described clinical spectrum and new approach to the management of stage III and IV ocular GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(2S1):49.

22. Rao, SN, Rao, RD. Efficacy of topical cyclosporine 0.05% in the treatment of dry eye associated with graft-versus-host disease. Cornea. 2006;25:674–678.

23. Lelli, GJ, Jr., Musch, DC, Gupta, A, et al. Ophthalmic cyclosporine use in ocular GVHD. Cornea. 2006;25:635–638.

24. Wang, Y, Ogawa, Y, Dogru, M, et al. Ocular surface and tear function after topical cyclosporine treatment in dry eye patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:293–302.

25. Kojima, T, Higuchi, A, Goto, E, et al. Autologous serum eye drops for the treatment of dry eye diseases. Cornea. 2008;27:S25–S30.

26. Jacobs, DS, Rosenthal, P. Boston scleral lens prosthetic device for treatment of severe dry eye in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Cornea. 2007;26:1195–1199.