Chapter 45 Occupational Rehabilitation

Epidemiology

Occupational injuries are both common and expensive. For example, occupational low back pain occurs in 2% of workers per year. In those younger than 45 years, low back pain is the most common cause of disability. Direct costs include medical expenses; indirect costs include lost worker productivity. The total annual direct costs are in excess of $65 billion; indirect costs are more than $106 billion. Occupational injuries and illnesses are insufficiently appreciated contributors to the total burden of health care costs.18

The largest and most expensive source of injuries is work-related musculoskeletal disorders. A National Academy of Sciences study found that musculoskeletal disorders of the back and arm cause more than 1 million workers to miss time from their job each year, at an annual cost of more than $50 billion.25 When one takes into account such indirect costs as reduced productivity, loss of customers as a result of errors made by replacement workers, and regulatory compliance, the total yearly cost of all workplace injuries is estimated to be well over $1 trillion, or 10% of the U.S. gross domestic product.23,24,26 A small percentage of injured workers account for a large percentage of costs. For example, 7.4% of cases of absence from work for 6 months in a cohort of occupational back pain claimants accounted for about 70% of lost days, medical costs, and wage replacement costs.1

History

Workers’ compensation acts were passed near the end of the nineteenth century in Germany (1884), Austria (1887), Great Britain (1897), and France (1898). In the United States, the Bureau of Labor Statistics was established in 1869 to study industrial accidents. The Employer’s Liability Law (1877) established the potential for employer liability in workplace accidents. After a long study of the German insurance plan, workers’ compensation legislation was finally passed into law in the United States in 1911. Further concerns over workers’ safety led to the formation of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970.10,12

Because workers’ compensation is state run, the rules of coverage vary. Each state can decide for itself how to define a work injury, how cases will be managed, and what benefits are provided. The federal government oversees workers’ compensation only for small specific groups such as railroad workers. This varied approach to injured workers is even more marked in other countries. In economies with a strong social benefit system, such as France, the injured workers do not return to work so quickly. Throughout much of the world, low back pain is considered a normal part of life rather than a severely disabling injury. This approach to low back pain is probably healthier and more cost-effective. Given the same level of back injury, compared with those in other countries, individuals in the United States are more disabled.30

Principles

An injury occurs after a specific event can be pinpointed at a particular place and time. This generally refers to minor trauma or a specific lifting injury. An example of an occupational injury would be a nurse’s aide hurting her back while lifting a patient. An occupational illness, on the other hand, comes on gradually. This can occur after repetitive microtrauma and can result in a cumulative trauma disorder such as carpal tunnel syndrome. Cumulative trauma disorder, repetitive motion disorder, and repetitive strain injury are among the terms used to refer to the work-related musculoskeletal disorders associated with occupational illness. Cumulative trauma disorder causation is multifactorial and generally is thought to include diagnoses such as carpal tunnel syndrome and lateral epicondylitis. A cumulative trauma disorder is not a specific medical diagnosis but is a general description. A pathoanatomic diagnosis is often not possible. Compared with other workers’ compensation cases, the mean cost per case of upper limb cumulative trauma disorders is nearly 10 times higher. Sixty percent of new occupational illnesses are associated with repetitive motion.21

Although occupational risk factors have been identified, recent literature shows less of a direct causation of overuse syndromes than was previously thought. For example, studies have shown that computer use does not pose a severe occupational hazard for developing symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome.2 Although there are psychologic risk factors for developing symptoms, there appears to be little scientific evidence for the effectiveness of biopsychosocial rehabilitation on repetitive strain injuries.16

Few high-quality studies of effective injury prevention have been published. One such large-scale, randomized, controlled trial of an educational program to prevent work-associated low back injury found no long-term benefits associated with training.3 Many employers include education regarding lifting techniques in new employee orientation. Nurses with mechanical lifting devices and lifting teams in their workplace are significantly less likely to have a musculoskeletal injury or disorder.8,13,14,32

Multiple risk factors are known for occupational injury claims. These include smoking, low educational status, job dissatisfaction, lower socioeconomic status, deconditioning, and previous history of injuries or disabilities. Other physical risk factors include repetitive motion, improper positioning, forceful movement, contact stresses, whole body vibration, cold temperatures, and unaccustomed work. It is less well known how altering these risk factors will affect injury rates.25 Workers with the greatest physical work requirements and those with the shortest duration of employment are at the highest risk of back injuries.11

Improving one’s flexibility, strength, and aerobic fitness reduces pain, improves sleep, and improves workplace functioning. A review of controlled trials looking at education, lumbar supports, exercises, ergonomics, and risk factor modification found that only exercise demonstrated sufficient evidence of back or neck pain prevention.19,33 A cohort study suggested that correct dynamic trunk extension performance can protect against back-related permanent work disability.29

Musculoskeletal fitness is a vital component of the overall health-related fitness equation that has not been fully appreciated. Achieving an adequate level of muscle strength and flexibility enhances dynamic joint stabilization. Joint stabilization helps prevent excessive load transmission across joints and reduces the abnormal movement patterns that can predispose one to injury.15

Personal modifiable factors are major influences in the recovery from work-related disorders. A relationship exists between subjective well-being and work ability in the general population. Life dissatisfaction predicts subsequent work disability, especially among the physically healthy.17 Factors associated with better recovery include exercise or physical activity outside work and lower stress levels. Factors associated with higher disability levels over time are cigarette smoking and bed rest.28 Although risk factors for developing occupational disability have been identified, overall there has been low predictive power of such regression models.27

Risk factors for delayed recovery have been identified and have been called yellow flags. Identifying yellow flags in individuals and using aggressive case management with them can be helpful in reducing workers’ compensation costs. Focusing on reducing the perception of disability at the time of injury is critical to preventing time loss.31 Non–return to work is associated with higher psychosocial morbidity.20 The doctor’s proactive communication regarding return to work can improve outcomes. According to a prospective study on doctor–patient communication, during the subacute or chronic phase (>30 days of disability), a 60% higher return to work rate was achieved from a positive return to work recommendation.4

Evaluations

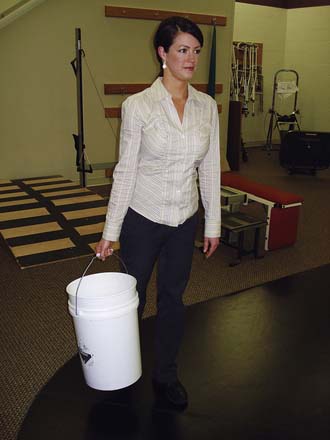

Job descriptions are generally available for each injured worker and should be reviewed to help identify whether that person can return to his or her regular job. Job site analyses done by ergonomists and occupational therapists can help to evaluate whether a worker can perform the particular job safely. These analyses can also help determine whether job modifications are needed to permit the worker to perform the job safely. Ergonomics refers to the study of how the human body interacts with the environment. Certain physical arrangements increase work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Ergonomists are experts in making modifications and suggestions to reduce the risks of injury (Figures 45-1 and 45-2).

FIGURE 45-2 Demonstration of proper lifting technique. Note that she flexed her knees, not her spine.

Preplacement evaluations can be helpful in finding work for an individual who has a higher than average risk for injury. Such persons should not be placed in a job that is known to have a high injury rate. Many employers, such as automotive manufacturers, perform median nerve conduction studies on new hires. These tests are considered a baseline and can be used for comparison purposes later if the employees develop carpal tunnel symptoms.

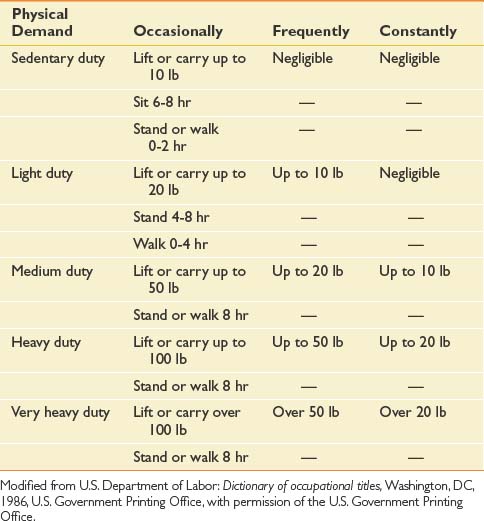

Restricted duty allows the injured worker to maintain current function and employment without risking further injury. This is often a better option than being off work. The Department of Labor has published a book called the Dictionary of Occupational Titles34 that clarifies categories of work. They are as follow: sedentary, light, medium, heavy, and very heavy. The occasional maximal lifting that corresponds to each of these is 10 lb, 20 lb, 50 lb, 100 lb, and more than 100 lb, respectively (Tables 45-1 and 45-2).

| Percentage of Day | Handling Repetitions | |

|---|---|---|

| Infrequent | 1-2 | 1-4 |

| Occasional | 3-33 | 5-32 |

| Frequent | 34-66 | 33-250 |

| Constant | 67-100 | 251-2000 |

Modified from U.S. Department of Labor: Dictionary of occupational titles, Washington, DC, 1986, U.S. Government Printing Office, with permission of the U.S. Government Printing Office.

Treatment

Acute Injury

Longer durations of the initial episode of care or work disability are among the most powerful predictors of recurrence. This implies that shorter episodes of care and early return to work contribute to better outcomes.35 A direct correlation exists between the number of days to first recheck and the days to final release of patients with back pain injuries. On average, reducing time between initial visit and first recheck by 1 day shortens the number of days to final release by 3.1 days.6 One study of occupational medicine physicians found that those with the best patient outcomes placed only 35% of their patients with low back pain on restrictions and kept less than 1% off work.7

Subacute Phase of Care

The subacute stage of care has been increasingly studied and found to be a critical period in preventing disability. Interventions in this stage that address maladaptive cognitions and behavior, as well as focus on return to work, have demonstrated reductions in lost work time and disability.9 Because of the incidence of serious pathology during the subacute phase, there is often an indication for imaging. In addition to imaging, injections can be helpful for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Injections can be performed with an anesthetic agent or a steroid medication, depending on the intended purposes. Maximizing functional recovery can be achieved with physical therapy. The physical therapy goals are to reduce pain as well as restore function and prevent reinjury.

Case Closure

A permanent partial impairment (PPI) rating might be appropriate once the point of MMI has been attained. The PPI rating is designed to compensate the individual for any future lost earnings as a result of their residual dysfunction after the work-related injury. If there was a preexisting condition, an adjustment or apportionment might be needed (Table 45-3). The most widely accepted methodology for evaluating impairment is the AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, published by the American Medical Association. It is updated periodically and is currently in its sixth edition. Several states require its use in PPI determinations, whereas other states allow or require the use of other editions or their own state guide.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Precipitation | Injury causes a “latent” disease process to appear |

| Acceleration | Injury hastens appearance of an underlying disease process |

| Aggravation | Permanent worsening of a previous condition by a particular event |

| Exacerbation | Temporary worsening of a previous condition by an injury |

| Recurrence | Signs or symptoms of a previous illness or injury occur in the absence of a new provocative event |

Modified from Demeter SL, Andersson GBJ, editors: Disability evaluation, ed 2, St Louis, 2003, Mosby, with permission.

Functional Capacity Evaluations

Functional capacity evaluations are extensive and formalized physical and occupational testing. FCEs are done by specially trained physical and occupational therapists. These evaluations last anywhere from 4 hours to 2 days. They assess many aspects of the person’s functioning. FCEs emphasize validity and consistency, overall functional ability, and the ability to perform a particular type of employment. The FCE often can guide or clarify what Dictionary of Occupational Titles category job the injured worker can perform. FCE testing is helpful in documenting inconsistencies, decreased effort, and lack of validity on repeat testing (Figures 45-3 to 45-10).

Vocational Rehabilitation

Vocational rehabilitation varies regionally in its availability and quality. Vocational rehabilitation is often recommended, after case closure has been reached, if an individual has persistent impairment and disability limiting his or her potential employment. Vocational rehabilitation is particularly helpful when workers are unable to return to their previous employment.

Medicolegal Aspects of Occupational Rehabilitation

Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a federal law designed to help protect the rights of disabled citizens. Employers cannot avoid hiring impaired persons solely because of their impairment and disability, as long as they are able to perform the key components of the job. Preemployment physicals are not allowed under the ADA. After an individual has been hired, however, a preplacement physical can be used to help find the most appropriate job for that individual. Employers are also responsible for making reasonable accommodations to allow disabled individuals to perform their job functions. An approved list notes diagnoses that are considered disabilities. The list also includes some diagnoses that can be perceived as disabilities (e.g., an able-bodied HIV-positive worker). This federal legislation is broad-sweeping and has not yet been fully tested in the courts, although case law continues to accumulate.

Causation

When doctors state their opinions on a medicolegal issue, they need to state them within “a reasonable degree of medical certainty.” This reasonable certainty means that, based on the available evidence, the truth of the statement is more likely than not. This corresponds to the civil law standard of “preponderance of the evidence.” Physicians’ scientific training prepares them to meet a higher standard of certainty (normally 95%). This corresponds to the criminal law standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Doctors are not expected to be that certain in medicolegal cases.22

1. Abenhaim L., Suissa S. Importance and economic burden of occupational back pain: a study of 2,500 cases representative of Quebec. J Occup Med. 1987;29:670-674.

2. Andersen J.H., Thomsen J.F., Overgaard E., et al. Computer use and carpal tunnel syndrome: a 1-year follow-up study. JAMA. 2003;289(22):2963-2969.

3. Daltroy L.H., Iversen M.D., Larson M.G., et al. A controlled trial of an educational program to prevent low back injuries. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:322-328.

4. Dasinger L.K. Doctor proactive communication, return-to-work recommendation, and duration of disability after a workers’ compensation low back injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43:515-525.

5. Demeter S.L., Andersson G.B.J., editors. Disability evaluation, ed 2, St. Louis: Mosby, 2003.

6. Derebery J., Anderson J.R. From Concentra Health Services analysis based on year-to-date [November 1999] data. Low back pain: an evidence-based, biopsychosocial model for clinical management. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Press; 2002.

7. Derebery J., Anderson J.R. Low back pain: an evidence-based, biopsychosocial model for clinical management. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Press; 2002.

8. Engkvist I.L., Hjelm E.W., Hagberg M., et al. Risk indicators for reported over-exertion back injuries among female nursing personnel. Epidemiology. 2000;11:519-522.

9. Feldman J.B. The prevention of occupational low back pain disability: evidence-based reviews point in a new direction. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(1):1-14.

10. Felton J.S. History of occupational health and safety. Introduction to occupational health and safety. Itasca, Ill: National Safety Council; 1986.

11. Gardner L., Landsittel D.P., Nelson N.A., et al. Risk factors for back injury in 31,076 retail merchandise store workers. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(8):825-833.

12. Goetsch D.L. Occupational safety and health, ed 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1996.

13. Guthrie P.F., Westphal L., Dahlman B., et al. A patient lifting intervention for preventing the work-related injuries of nurses. Work. 2004;22:79-88.

14. Hignett S., Crumpton E., Ruszala S., et al. Evidence-based patient handling: systematic review. Nurs Stand. 2003;17(33):33-36.

15. Hunt A. Musculoskeletal fitness: the keystone in overall well-being and injury prevention. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;1(409):96-105.

16. Karjalainen K., Malmivaara A., van Tulder M., et al. Biopsychosocial rehabilitation for upper limb repetitive strain injuries in working age adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:1.

17. Koivumaa-Honkanen H., Koskenvuo M., Honkanen R.J., et al. Life dissatisfaction and subsequent work disability in an 11-year follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):221-228.

18. Leigh J.P., Markowitz S.B., Fahs M., et al. Occupational injury and illness in the United States: estimates of costs, morbidity, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1557-1568.

19. Linton S.J., van Tulder M.W. Preventive interventions for back and neck pain problems: what is the evidence? Spine. 2001;26:778-787.

20. Mason S. Outcomes after injury: a comparison of workplace and nonworkplace injury. J Trauma. 2002;53:98-103.

21. Melhorn J.M. Cumulative trauma disorders and repetitive strain injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;351:107-126.

22. Melhorn J.M. Impairment and disability evaluations: understanding the process. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(12):1905-1911.

23. Melhorn J.M., Gardner P. How we prevent prevention of musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace. Clin Orthop. 2004;419:285-296.

24. Melhorn J.M., Wilkinson L.D., O’Malley M.D. Successful management of musculoskeletal disorders. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment Journal. 2001;7(7):1801-1810.

25. National Academy of Sciences. Musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace: low back and upper extremities. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2001.

26. National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Work related musculoskeletal disorders: report, workshop summary, and workshop papers. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, Institute of Medicine; 1999. 1–240

27. Okurowski L., Pransky G., Webster B., et al. Prediction of prolonged work disability in occupational low-back pain based on nurse case management data. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:763-770.

28. Oleske D.M., Neelakantan J., Andersson G.B., et al. Factors affecting recovery from work-related, low back disorders in autoworkers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(8):1362-1364.

29. Rissanen A., Heliovaara M., Alaranta H., et al. Does good trunk extensor performance protect against back-related work disability? J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:62-66.

30. Sanders S.H., Brena S.F., Spier C.J., et al. Chronic low back pain patients around the world: cross-cultural similarities and differences. Clin J Pain. 1992;8:317-320.

31. Tate R.B., Yassi A., Cooper J. Predictors of time loss after back injury in nurses. Spine. 1999;24(18):1930-1936.

32. Trinkoff A.M., Brady B., Nielsen K. Workplace prevention and musculoskeletal injuries in nurses. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(3):153-158.

33. Tveito T.H., Hysing M., Eriksen H.R. Low back pain interventions at the workplace: a systematic literature review. Occup Med. 2004;54:3-13.

34. US Department of Labor. Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1986.

35. Wasiak R. Risk factors for recurrent episodes of care and work disability: case of low back pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:68-76.