Chapter 65 Occupational dermatology

1. What is the most common type of skin disease due to workplace exposures?

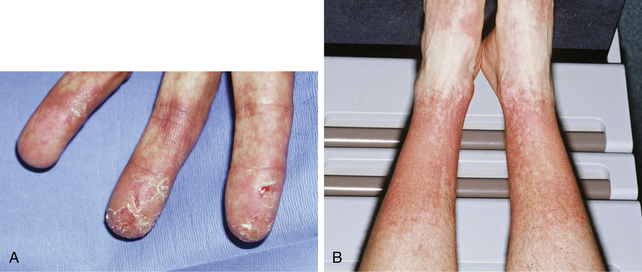

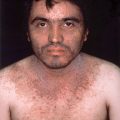

Contact dermatitis accounts for >90% of occupational skin disease (OSD) cases. The most common location of job-related contact dermatitis is workers’ hands. It is generally accepted that 80% of the contact dermatitis cases are irritant (Fig. 65-1), while 20% are allergic (Fig. 65-2). Recent studies have challenged those figures, demonstrating that up to 40% of work-related skin diseases were from allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). Pure allergic contact dermatitis in the occupational setting is uncommon because a component of irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is frequently present. Bureau of Labor and Statistics data show that OSD accounted for 16.5% of all occupational illnesses in 2005. Some have estimated the true number of cases to be 10 to 50 times higher than that due to underreporting and underdiagnosis. The “standard” allergens patch test screens for only approximately 75% of common allergens, so additional specialized testing with industrial chemicals to which the worker is exposed is frequently warranted. Testing should only be done with known materials in accepted concentrations.

Lushniak, BD: Occupational contact dermatitis, Dermatol Ther 17:272–277, 2004.

3. Are there any risk factors for the development of an OSD?

Various investigators have found a personal history of atopic dermatitis to be a significant risk factor. Other preexisting skin diseases with compromised epidermal barriers, such as xerosis or nummular eczema, can predispose a person to contact dermatitis because of enhanced absorption of irritants and allergens through the skin. Poor personal hygiene plays a role in patients who neglect to wash off irritating and sensitizing chemicals, thereby prolonging contact time. However, overwashing is actually the more common problem. The use of harsh soaps and frequent wetting/drying cycles induce chapping and desiccation, which compromises the skin barrier. Environmental factors are also important. If it is hot and humid, workers may perspire, which can solubilize particulate matter, enhancing its penetration into the skin. Sweat can also leach out allergens, such as chromates from leather shoes, inducing an allergic contact dermatitis. Conversely, low temperature and humidity causes chapping of the skin, which can lead to irritant contact dermatitis. Certain jobs also are more likely to be associated with OSD, such as nursing and health care aides.

4. My patient has a hand dermatitis that appeared to begin at his job. Does this mean he has an occupationally related skin disease?

Not necessarily. Just because a patient has a rash, and he or she works, does not mean it is job-related. To help make that determination, investigators have outlined seven criteria to be assessed. Four out of the seven should be present for reasonable medical probability:

1. Is the eruption consistent with a contact dermatitis? It should look like an eczematous dermatitis and not like other disorders (i.e., vasculitis).

2. Are there occupational exposures to possible irritants or allergens? There should be known documented irritating or sensitizing compounds to which the patient has been exposed at work.

3. Is the anatomic location of the eruption consistent with the exposure a worker would obtain on the job? For example, a worker may handle a chemical daily and break out with dermatitis only on his back. This is not consistent with an OSD because he should have developed an eruption where he contacted the compound the most, namely, his hands.

4. Is the onset and time course of the eruption consistent with contact dermatitis? Allergic contact dermatitis is a delayed reaction (occurring 48 to 72 hours after exposure), while irritant reactions may be immediate or delayed. Contact dermatitis is not, for example, consistent with a worker’s one-time exposure to a chemical when a rash occurs 3 months after that one incident.

5. Are nonoccupational exposures excluded as a possible cause of the dermatitis? Hobbies, second jobs, and household contactants should be pursued as possible sources of contact dermatitis.

6. Does the eruption improve away from work? Work-related eruptions tend to improve when a worker is away from his job, although sometimes the same allergens and irritants may be found at home. Also, approximately 25% of workers with an OSD have a chronic and persistent dermatitis despite leaving their job and therapeutic intervention, and improvement does not occur when the worker is away from his place of employment.

7. Does patch testing reveal a likely causative agent? If a positive patch test reveals a likely allergen source with which the worker had contact, it is useful for pointing to the job exposure as the problem. However, patch tests must be interpreted within the context of the patient’s history and physical examination. A positive test does not necessarily mean the allergen is responsible for the patient’s current dermatitis, because it could be unrelated sensitization. The patch test reaction must always be assessed for its relevance to the present eruption.

5. How do I find out what a worker is exposed to on his job?

By law, employers must provide their employees information regarding all possible workplace exposures. Each of these information sheets, known as Material Safety Data Sheets, has information about a particular compound, including hazardous ingredients that it contains in concentrations >1%. They also list the manufacturer’s name and phone number, which is useful for the dermatologist to check on other ingredients, because many cutaneous allergens are present in the final product in concentrations <1%. Dermatology and occupational medicine textbooks also provide general lists of allergens and irritants that may be specific to a particular occupation. On occasion, a more in-depth investigation may require a visit to the patient’s place of employment. It is a unique opportunity to observe the worker performing his duties, the general working conditions, protective measures used, and other contactants that the patient might have overlooked.

Adams R: Occupational skin disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1999, WB Saunders.

6. What are some typical workplace irritants and allergens?

• Irritants: Water, soaps and detergents, solvents, particulate dusts, food products, fiberglass, plastics, resins, oils, greases, agricultural chemicals, and metals. Of note, irritating compounds can be allergenic, and allergenic compounds can be irritating.

• Allergens: Metals (e.g., nickel), germicides (e.g., formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde), plants (e.g., poison ivy), rubber additives (e.g., thiurams), organic dyes (e.g., para-phenylenediamine in hair dye), plastic resins (e.g., acrylics and epoxies), and first-aid medications containing neomycin.

Table 65-1 summarizes possible contactants associated with common occupations.

Table 65-1. Selected Occupations and Their Possible Contactants

| OCCUPATIONS | IRRITANTS | ALLERGENS |

|---|---|---|

| Construction workers | Cleansers, solvents, cement, dirt | Chromium (cement, leather boots), rubber chemicals (gloves), epoxy resin (adhesives) |

| Hairdressers | Shampoo, water, permanent wave solutions | Para-phenylenediamine (hair dyes), formaldehyde (shampoos), fragrances (shampoos and cosmetics), glyceryl monothioglycolate (permanent hair wave solutions) |

| Housekeepers | Cleansers, disinfectants, water | Rubber chemicals (gloves), fragrances and preservatives (cleaning and disinfectant solutions) |

| Health care workers | Soap, water, gloves, disinfectants | Rubber chemicals (gloves), glutaraldehyde (cold sterilizer for instruments), preservatives (skin care products) |

| Photographers | Water, developers, fixers, bleaches | Color developers, black and white developers |

Elsner P: Occupational dermatoses. In Burgdorf WH, Plewig G, editors: Braun-Falco’s dermatology, ed 3, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009, Springer, pp 402–408.

7. What is the prognosis of an OSD?

In general, workers with occupational hand dermatitis do not fare well. Approximately 25% have complete remission, 50% have periodic recurrences, and 25% have chronic persistent dermatitis, despite a change in jobs and therapeutic intervention. Some remediable reasons for persistent dermatitis include failure to diagnose and remove the sensitizer responsible for allergic contact dermatitis, continued exposure to nonspecific irritants at home and work, continued inadvertent allergen exposure, and secondary sensitization (e.g., to preservatives contained in moisturizers and topical steroids that physicians give as treatment). Early diagnosis can be important in preventing chronic OSD. Studies have shown that delay of diagnosis for more than 1 year and continual exposure are crucial factors for chronicity.

8. Aren’t gloves enough protection for preventing OSD?

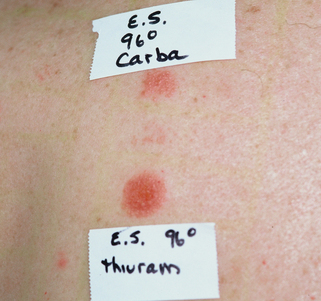

No. There is a widespread misconception that gloves guarantee safety. Although gloves are recommended on a routine basis to protect against environmental insults, they are also the cause of a great deal of contact dermatitis themselves. Irritant dermatitis occurs because patients sweat underneath their gloves. Allergic contact dermatitis occurs commonly with rubber gloves containing the chemicals thiuram, mercaptobenzothiazole, and carbamates, which are “rubber accelerator” chemicals used to speed up the vulcanization process. Some allergens can penetrate various glove materials and become trapped against the skin. For example, acrylics, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, and epoxy resins all penetrate latex gloves (Fig. 65-3).

9. How do you treat an occupationally related skin disease?

Remove the allergen and as many irritants as possible from both work and home. Allergens must be substituted with less sensitizing alternatives. For example, vinyl gloves can be used in place of rubber gloves. Patients must be instructed to avoid both excessive water exposure and frequent hand washing. The constant wetting and drying can lead to chapping, which makes all hand dermatitis worse. Hands can be protected from the elements by using cotton glove liners to absorb perspiration inside a proper protective glove for the job. Moisturizers should be used immediately after wetting the hands or whenever they appear dry and scaling. Topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy for occupational contact dermatitis, with systemic steroids reserved for acute, severe situations. Other treatments for severe chronic OSD have included cyclosporine, methotrexate, topical tacrolimus, and phototherapy. With treatment and hand protection, many workers can and do continue to work despite a hand dermatitis. Job change should only be considered in patients whose inadvertent and direct exposure to irritants or an allergen cannot be eliminated adequately. Most workers suffer financial and social consequences from changing occupations and do best with environmental modifications that allow them to remain on their job.