Chapter 23 OCCULT GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING AND IRON DEFICIENCY ANAEMIA

This chapter concentrates on unexplained or occult gastrointestinal bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract and small intestine.

AETIOLOGY

Arteriovenous malformations

Bleeding may be occult or severe. The most common presentation is with haematemesis or melaena. The diagnosis of gastric AVMs is made with upper endoscopy and in the small intestine using capsule endoscopy. The lesions are bright red and well circumscribed and they may be flat or raised. It is frequently difficult to determine whether a visualised AVM is the actual bleeding site. Generally, evidence for bleeding is required, as indicated by active bleeding from the lesion or an affixed clot.

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

The treatment of PHG consists of addressing the underlying portal hypertension. Unlike variceal bleeding, this condition cannot be treated with band ligation. Effective treatment requires a reduction in portal pressure. This can be accomplished with β-blockers, such as propranolol, portal decompression using radiological placement of a transjugular, portosystemic intrahepatic shunt, or surgical shunting. Somatostatin infusion is routine first-line treatment for actively bleeding cirrhotic patients with PHG.

Small intestine neoplasms

Benign small intestine tumours are more common than malignant tumours. Of these, the leiomyomas are most frequently associated with bleeding. Frequently, abdominal pain and nausea are associated presenting symptoms. Leiomyomas are diagnosed endoscopically and, in recent times, increasingly using capsule endoscopy. Arteriography demonstrates a well circumscribed tumour blush in most lesions. Treatment for all symptomatic leiomyomas is surgical resection, because they are macroscopically indistinguishable from malignant leiomyosarcomas. Adenomas are the most common mucosal tumour of the small intestine, typically occurring in the periampullary region. Bleeding may occur in large polypoid lesions. All adenomas should be removed, usually endoscopically, because of the risk that they may progress to carcinoma. Other small intestine tumours such as carcinoids, adenocarcinomas, lymphomas and metastatic disease can also present with chronic blood loss.

Aorto-enteric fistulas

Aorto-enteric fistulas are a rare source of chronic blood loss but frequently present with massive haemorrhage, usually in the form of haematemesis, melaena or haematochezia. Consequently, this condition is life-threatening. Think about this possibility in anyone who has had an aortic graft or a diagnosed aortic aneurysm. Most fistulas communicate with the third or fourth portion of the duodenum. Fistulas may be primary and associated with aneurysms, or secondary, following aortic reconstructive surgery. Characteristically, the bleeding is intermittent, often starting with a ‘herald bleed’ and subsequently (usually within 1–3 weeks) presenting with an exsanguinating haemorrhage. Ultimately the diagnosis is made at laparotomy, although endoscopic visualisation with upper endoscopy or push enteroscopy and aortography can make the diagnosis in up to 50% of cases.

Treatment-induced mucosal lesions

Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may cause small intestinal inflammation, ulceration and web-like structures, which, if sufficiently severe, may result in blood loss presenting as haemoccult-positive stools and iron deficiency anaemia. Such medication-induced mucosal lesions are best diagnosed with capsule endoscopy.

INVESTIGATION OF UNIDENTIFIED GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

The discussion is based on the premise that the patient has already had a gastroscopy and colonoscopy, which have not been able to identify the source of bleeding (see Table 23.2).

Small bowel series and enteroclysis

Positive findings on routine small bowel series are rare in patients presenting with bleeding of obscure origin. While Crohn’s disease is often diagnosed with the use of this standard examination, only around 5% of small bowel follow-through examinations detect an intestinal bleeding site. Overall, therefore, a small bowel series is regarded as a poor test for elucidating the source of occult gastrointestinal bleeding.

Nuclear scans

A Meckel’s scan using technetium-99m pertechnetate is used to identify a Meckel’s diverticulum.

Angiography

Angiography can detect bleeding at a rate of 0.5 mL/min and can localise a site of bleeding in 50%–70% of patients with massive haemorrhage. However, the yield decreases to around 25% when active bleeding has slowed or stopped. In addition to demonstrating active bleeding, angiography can diagnose non-bleeding lesions such as angiodysplasias and small bowel tumours. When haemorrhage is active, the site of bleeding is usually identified rapidly by technetium-labelled red blood cell scan and/or mesenteric angiography. If no diagnosis can be made, and the patient continues to bleed profusely, exploratory surgery is sometimes essential. Intraoperative enteroscopy is frequently performed initially as an aid to making a diagnosis.

Capsule endoscopy

The capsule is propelled via peristalsis through the gastrointestinal tract, capturing about 55,000 digital images and is excreted in the faeces. CE has become an important investigative tool in patients with occult gastrointestinal bleeding, suspected small intestine tumours and other abnormalities. Its interplay with the new technique of double balloon enteroscopy enables the small intestine to receive proper attention, similar to other parts of the gastrointestinal tract.

SUMMARY

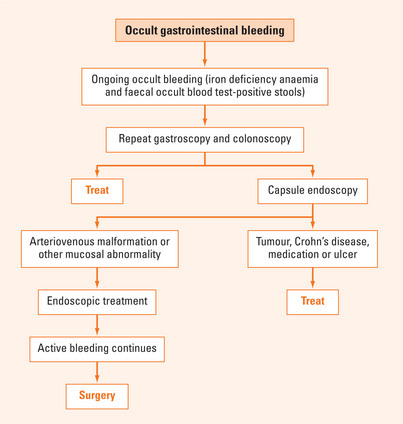

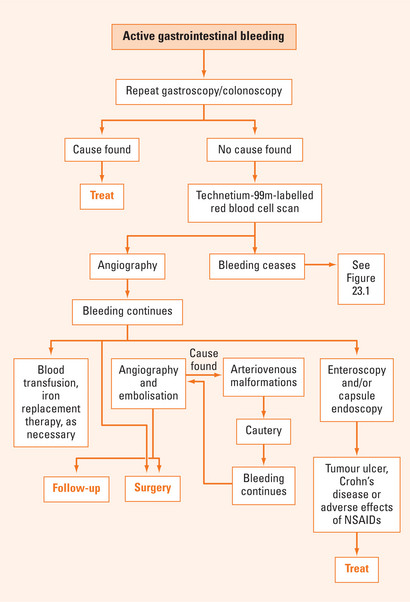

Patients presenting with obscure gastrointestinal haemorrhage represent a difficult diagnostic and management problem. This patient group frequently requires sophisticated investigations in an effort to make a specific diagnosis. Patients with anaemia and faecal occult blood test-positive stools can be investigated as outpatients (Figure 23.1). However, patients who present with massive haemorrhage certainly require prompt hospital referral for resuscitation and further investigation (Figure 23.2). When gastroscopy and colonoscopy fail to identify a source of bleeding, it may be necessary to investigate the small intestine. While radiological techniques are still frequently utilised, the advances in technology such as capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy are now incorporated into clinical practice.

Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, et al. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95.

Eliakim AR. Video capsule endoscopy of the small bowel (PillCam SB). Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:124-127.

Martins NB, Wassef W. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:612-619.

May A, Nachbar L, Pohl J, et al. Endoscopic interventions in the small bowel using double balloon enteroscopy: feasibility and limitations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:527-535.

Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:699-718.