Chapter 7 Obstructive sleep apnea: decision making and treatment algorithm

1 INTRODUCTION

Numerous treatment options for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) presently exist. These treatments range from non-invasive behavioral modifications to nightly use of positive airway pressure (PAP) devices to surgical treatments that alter airway anatomy. Selection of patients for these treatments is complex given the range of variability in patient anatomy and physiology, patient preference, disease severity, and controversy with regard to the effectiveness of available treatments. The threshold for treatment is also in flux with some arguing that symptoms of sleepiness are more important than measured disease severity in most patients.1 What can result from this is a confusing array of treatment options and treatment guidelines which leave patients and physicians unsure as to what decision is most appropriate for the individual. This chapter seeks to provide a framework for these issues and a guide for synthesis and evaluation of treatment options in this disease.

2 DEFINITIONS OF DISEASE

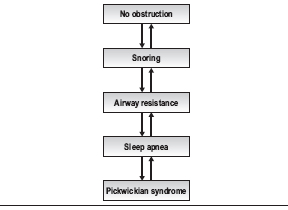

Sleep-disordered breathing can be viewed as a continuum from normal non-obstructed breathing at one end to a patient with sleep apnea and Pickwickian syndrome at the other (Table 7.1). The level of disease in an individual patient can improve or worsen, moving the patient up or down this continuum both over time and on a night-to-night basis. For instance, a normal patient who gains a significant amount of weight may begin to snore, develop arousals during the night and begin to move into a disease state. With additional weight gain, this patient may develop increased airway resistance or sleep apnea. A patient who consumes alcohol on a given night can also move on the scale in a similar fashion; as muscle tone decreases, obstruction increases. Similarly, a patient with sleep apnea who loses weight may develop less severe airway resistance, simple snoring, or even achieve a normal state of breathing at night. Thus, the number generated on a polysomnogram must be viewed in the context of the patient’s overall disease and night-to-night variation of their sleep-disordered breathing.

Table 7.1 The continuum of sleep disordered breathing

Although there are numerous metrics to measure the severity of obstructive sleep apnea, disease severity is generally described in terms of the number of apneas plus hypopneas per hour of sleep, or via the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) and O2 saturation as measured on an overnight sleep study, or polysomnogram. The polysomnogram represents a snapshot in time which may not reflect a patient’s level of disease over a long period of time, but it is still the best measure of disease severity available at present.

Lastly, a respiratory effort-related arousal (RERA) is an event that occurs when a patient develops an arousal on electroencephalogram in conjunction with increasing inspiratory effort during sleep. RERAs can be added to apneas and hypopneas to create the Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) which many use to guide treatment.2

3 EFFECTS OF SLEEP APNEA AND TREATMENT THRESHOLDS

The physiological manifestations are important and principally relate to cardiovascular consequences of OSA, though there are other physiological effects of disordered breathing during sleep, such as alterations in inflammatory biomarkers, which also occur. Cardiovascular consequences include associations with stroke, hypertension and myocardial infarction and are being studied rigorously in the Sleep Heart Health Study, which is longitudinally tracking a cohort of OSA patients with measures of OSA and medical outcomes.3

The behavioral effects of sleep disruption are commonly evident. These may manifest as tiredness in the morning or daytime, falling asleep in permissive situations such as watching TV or reading a book, an increased incidence of motor vehicle accidents, and losses of concentration and productivity. A simple patient self-report scale, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, was designed to quantify this level of tiredness4 though there are also objective measures of alertness such as the psychomotor vigilance test.5 The behavioral effects of OSA can be variable among patients where a patient with snoring may have significant tiredness whereas a patient with an elevated AHI and greater nighttime obstruction may not display tiredness. This discrepancy appears to make behavioral measurement alone insufficient to fully characterize the disease or its treatment.

In light of the variability in the manifestation of OSA in patients and the gaps in our knowledge as to which patients will suffer cardiovascular consequences of this disease, significant controversy exists with respect to selection of patients for OSA treatment. In a review article on OSA, Ward Flemons writes, ‘In the majority of patients without coexisting conditions … the primary reason to test for and treat sleep apnea is the potential to improve the quality of life.’1 Studies vary in determining the magnitude of effects of mild to moderate OSA on hypertension and cardiovascular consequences. However, ongoing studies of large cohorts of patients such as the Sleep Heart Health Study are yielding important data that will provide guidelines for treatment in the future.6 With information on physiological consequences of OSA such as effects on inflammatory and other biomarkers as well as data from the Sleep Heart Health Study emerging, our threshold and circumstances for intervention will certainly evolve.

Nevertheless, physicians are faced today with patients needing treatment and decisions must be made. The best available evidence is synthesized to assist with these decisions, and treatment thresholds developed. In an attempt to help delineate a treatment threshold, one oft-quoted study determined that patients with an Apnea Index (AI) of >20 were at increased cardiovascular risk.7 Many use the cut-off of an AHI of 20 as the threshold for treatment (note the original cut-off of AI >20 has been subsequently adopted as AHI >20). While virtually all admit that patients with an AHI of >30 should be treated regardless of co-morbidity or behavioral effects, rigorous evidence for treatment of patients with an AHI of <30 is lacking.2 However, patients with AHI <30 with significant co-morbidity or behavioral effects (e.g. tiredness, loss of concentration) are also considered candidates for treatment of OSA.

It is the opinion of the author that all patients with an AHI >30 should be treated for OSA and symptomatic patients with an AHI <30 should be treated. Patients with an AHI <30 may have other factors that bring them to treatment including medical co-morbidities or other parameters on the polysomnogram that mandate treatment (e.g. low oxygen saturation, arrhythmias).

4 EVALUATION FOR OSA

4.1 HISTORY

A history of snoring, gasping, or witnessed apneas may be characteristic of sleep-disordered breathing, and the duration of the problem should be noted. Patients may be tired in the morning or daytime and may fall asleep in permissive situations. Patients should be generally questioned about their sleep habits and relevant history. Various questionnaires are available to evaluate the patient with sleep-disordered breathing. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is particularly easy to administer, it is quantitative, and gives insight into the degree of sleepiness that the patient is experiencing.4

4.2 PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On physical examination, the patient’s height and weight, height 1 year and 5 years ago, and neck circumference should be recorded. Examination of the nose, oral cavity, oropharynx, bony structure of the head and neck, and a fiberoptic examination should be undertaken. Sleep endo-scopy has been used more commonly in the evaluation to further examine patients in a pharmacologically induced state of sleep.8 Fiberoptic endoscopy is performed during pharmacologically induced sleep to determine the site of airway collapse, typically using propofol. It is hoped that use of this method will increase the accuracy in determining the site of obstruction in patients with OSA.

4.3 ADJUNCTIVE STUDIES

Adjunctive studies such as polysomnography are typically necessary if the patient’s history and examination point toward sleep-disordered breathing as a possibility. The type of study may be a full-night diagnostic study, a split-night study with the CPAP trial, or a home study. In some patients, multiple sleep latency tests or arterial blood gases may be helpful in discerning the effects of sleep-disordered breathing or differentiating OSA from narcolepsy. Cephalometric radiography may help in delineating the bony structure of the patient by assessing craniofacial abnormalities that may guide treatment. Additional imaging studies, such as static and dynamic MRI and CT scanning, have been used in protocols for upper airway assessment, though no data support their clinical use at this point.9

5 TREATMENT OPTIONS

5.1 BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION

In general, all patients should be informed of behavioral modifications that can reduce or eliminate OSA without the need for medicines, device use, or surgery. In patients with moderate or severe OSA, these maneuvers are not likely to be effective as stand-alone therapy; however, they can help to mitigate some effects of OSA in these patients and can also assist in education of the patient in the pathogenesis of their disease (e.g. with regard to weight loss or sleep position).

Behavioral modifications include principally sleep position therapy, weight loss where appropriate, and avoidance of sedatives, alcohol, or large meals before bedtime. In sleep position therapy, the patient sleeps on their side or stomach as opposed to on the back, as most patients obstruct more in the supine position. Pillows or positioners can be helpful to assist in this type of postural therapy. Patients should be encouraged to lose weight if they are overweight or obese, as weight loss reduces the bulk of tissue in the neck which narrows the airway, and reduces airway collapse. As surgical intervention for obesity has become safer and more refined, recommendations for surgical treatment of obesity are becoming more common.10 Patients should be counseled to avoid sedatives, including alcohol and other medications prior to bedtime, as sedatives may be important in causing loss of muscle tone and causing airway collapse during sleep. Eating a large or fatty meal or one replete with carbohydrates before bedtime can have the same effect by reducing muscle tone during sleep and should be avoided.

5.2 DEVICES THAT CAN BE WORN

Positive airway pressure (PAP)

The delivery of positive airway pressure is available in many forms, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure, automatically titrating positive airway pressure, and demand positive airway pressure. A description of each is beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it to say that each provides posi-tive pressure to the airway through a device worn on the face, and serves as an internal pneumatic splint for the airway. CPAP, which is the most commonly used form of PAP, typically uses between 5 and 15 cm of water pressure to maintain airway patency. These devices have the advantage of a high rate of effectiveness in the laboratory setting in reversing sleep-disordered breathing. Unfortunately, not all patients are able to wear the device regularly in the home setting, making compliance a significant issue. Additionally, patients frequently misrepresent their PAP use as being more compliant, necessitating close follow-up and the use of covert monitoring that is integrated into the device.11 Issues with regard to use of PAP such as desensitization of the patient to mask use at night, comfort and leaking at the mask interface, and claustrophobia must be reconciled and may require working with the patient intensively.

Oral appliances

Oral appliances, principally a mandibular repositioning device, can also be used for sleep-disordered breathing.12 Mandibular repositioning devices advance the mandible anteriorly, which brings forward the tongue and other muscles of the oropharynx and hypopharynx. The position of the palate is also changed with the mandibular repositioning device, likely through action of the palatoglossus muscle, and airway patency is typically improved. It is used principally for patients with simple snoring and mild apnea and has reduced effectiveness in patients with more severe disease.12 Patients with pre-existing disorders of the temp-oromandibular joint and edentulous patients are not considered to be good candidates for this device. As with PAP, no training of the airway occurs, therefore nightly use is necessary for treatment effect.

5.3 SURGICAL THERAPY FOR OSA

Surgical therapy for OSA can be classified in three categories. The first category includes procedures on the upper airway which may improve PAP use and compliance. The second category includes surgery that improves OSA without surgically altering the upper airway such as tracheotomy and bariatric surgery. The third category includes surgery that directly alters the upper airway to reduce obstruction of breathing during sleep.

Surgical procedures to improve PAP use

Patients who tolerate PAP and whose sleep-disordered breathing is abolished by PAP do not typically need surgery. However, there is a significant number of patients who do not tolerate PAP because of the need for elevated pressures or because of nasal obstruction. In selected patients with elevated pressures, surgery on the upper airway can reduce PAP pressures and improve compliance. Examples include patients with large tonsils, adenoid hypertrophy or nasal obstruction. If medical treatment of these issues fails, surgical treatment including tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, or nasal surgery may help reduce PAP pressures and/or improve compliance.13 Obstruction from turbinate hypertrophy, deviated septum, or nasal polyps, for example, may benefit from surgical correction.

Non-upper airway surgery for OSA

Despite its efficacy in bypassing upper airway obstruction, tracheotomy is rarely considered as a sole treatment for patients with OSA.14 More commonly, tracheotomy is used on a temporary basis in the perioperative period for patients undergoing upper airway surgery for OSA. The need for an opening in the neck with its associated hygiene and social burdens appropriately limits its routine use. Tracheotomy is typically reserved for morbidly obese patients who are unable to tolerate PAP, morbidly obese patients with Pickwickian syndrome who require upper airway bypass and nocturnal ventilation, and patients who are unable to tolerate PAP with significant co-morbidities in whom other treatment options have failed.14

Since a significant number of patients with OSA are obese and obesity is a major cause of OSA, bariatric surgery has the potential to significantly reduce a patient’s weight and improve sleep-disordered breathing. Bariatric surgery should be considered in patients with a BMI >40 or patients with a BMI >35 with significant medical co-morbidities.10 Patients who fall into this category should preferably be referred to an appropriate center for bariatric surgery for evaluation. This therapy has the significant advantage of treating other co-morbidities associated with obesity such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease in addition to OSA.10

6 ALGORITHM FOR TREATMENT OF OSA AND TREATMENT GOALS

The goal for treatment for OSA is to alleviate sleep-disordered breathing completely when possible manage the disease if complete cure is not possible. Re-evaluation after a treatment has been instituted is critical to determining treatment success. If one cannot normalize a patient completely, one attempts, at minimum, to move the patient into a less severe disease state through behavioral treatments, application of positive airway pressure, or surgery.

| Disease severity* |

|---|

| Mild (5<AHI<15) |

| No symptoms |

| Behavioral modification |

| Symptoms |

| Behavioral modification |

* Additional parameters from the polysomnogram, such as oxygen desaturation nadir, RERAs, and time spent below oxygen saturation of 90% can also be used to guide treatment, as these can shift a patient in to a higher category of disease severity.

1. Flemons WW. Obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl. 2002;347(77):498-504.

2. Loube DI, Gay PC, Strohl KP, Pack AI, White DP, Collop NA. Indications for positive airway pressure treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: a consensus statement. Chest. 1999;115(3):863-866.

3. Quan SF, Howard BV, Iber C, et al. The Sleep Heart Health Study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997;20(12):1077-1085.

4. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

5. Canisius S, Penzel T. Vigilance monitoring – review and practical aspects. Biomed Tech (Berl). 2007;52(1):77-82.

6. Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):19-25.

7. He J, Kryger MH, Zorick FJ, Conway W, Roth T. Mortality and apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea. Experience in 385 male patients. Chest. 1988;94(1):9-14.

8. Croft CB, Pringle M. Sleep nasendoscopy: a technique of assessment in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991;16(5):504-509.

9. Ahmed MM, Schwab RJ. Upper airway imaging in obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12(6):397-401.

10. Crookes PF. Surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:243-264.

11. Kribbs NB, Pack AI, Kline LR, et al. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(4):887-895.

12. Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, Schmidt-Nowara W. Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 2006;29(2):244-262.

13. Zonato AI, Bittencourt LR, Martinho FL, Gregorio LC, Tufik S. Upper airway surgery: the effect on nasal continuous positive airway pressure titration on obstructive sleep apnea patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(5):481-486.

14. Kim SH, Eisele DW, Smith PL, Schneider H, Schwartz AR. Evaluation of patients with sleep apnea after tracheotomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:996-1000.