CHAPTER 8 Obstetrics

Anaesthesia for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy

In descending order of preference:

Regional anaesthesia

Epidurals give excellent/satisfactory analgesia in 91% of mothers. Increased use of regional techniques probably accounts for the continuing reduction in maternal mortality by avoiding risks of failed intubation and aspiration. Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET) 2001 showed that women requesting analgesia for pain relief were more likely to require instrumental delivery if receiving 0.25% bupivacaine boluses rather than low dose bupivacaine infusion or combined spinal/epidural, but no significant difference in LSCS rates between groups (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Advantages and disadvantages of epidural anaesthesia

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Maternal participation at delivery | May take too long to perform if there is fetal distress |

| Avoids risk of failed intubation | Hypotension |

| Reduced risk of aspiration | Risk of patchy, incomplete block |

| Avoids morbidity from GA drugs | Backache |

| Avoids risk of awareness | Urinary retention |

| Earlier breast-feeding | |

| Good postoperative analgesia | |

| Less postnatal depression |

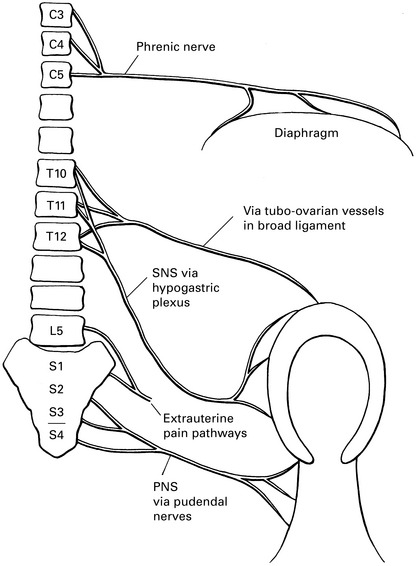

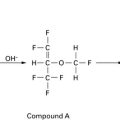

Pain pathways (Fig. 8.1)

LSCS stimulates sensory nerves to T10 in addition to phrenic. Aim to block from T8 to S5.

Aspiration

Postpartum

Oaa/Aagbi Guidelines for Obstetric Anaesthesia Services

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for obstetrical anesthesia. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Task Force on Obstetrical Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:600-611.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and the Obstetric Anaesthetists Association. Revised Guidelines, 2005. OAA/AAGBI guidelines for obstetric anaesthesia services. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Bogod D.G. The postpartum stomach – when is it safe? Editorial. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:1-2.

Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET) Study Group UK. Effect of low-dose mobile vs traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:19-23.

Duley L., Neilson J.P. Magnesium sulphate and pre-eclampsia. BMJ. 1999;319:3-4.

Gomar C., Fernandez C. Epidural analgesia–anaesthesia in obstetrics. Eur J Anaesth. 2000;17:542-558.

Levy D.M. Emergency caesarean section: best practice. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:786-791.

McDonnell N.J., Keating M.L., Muchatuta N.A., et al. Analgesia after caesarean delivery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:539-551.

McGlennan A., Mustafa A. General anaesthesia for caesarean section. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2009;9:148-151.

Ong K.-B., Sashidharan R. Combined spinal–epidural techniques. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:38-41.

Levy D.M. Anaesthesia for caesarian section. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:171-176.

Macarthur A.J., Gerard W. Ostheimer ‘What’s new in obstetric anesthesia’ lecture,. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:777-785.

McGrady E., Litchfield K. Epidural analgesia in labour. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2004;4:14-17.

May A. Obstetric anaesthesia and analgesia. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1186-1189.

Morris S. Management of difficult and failed intubation in obstetrics. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:117-121.

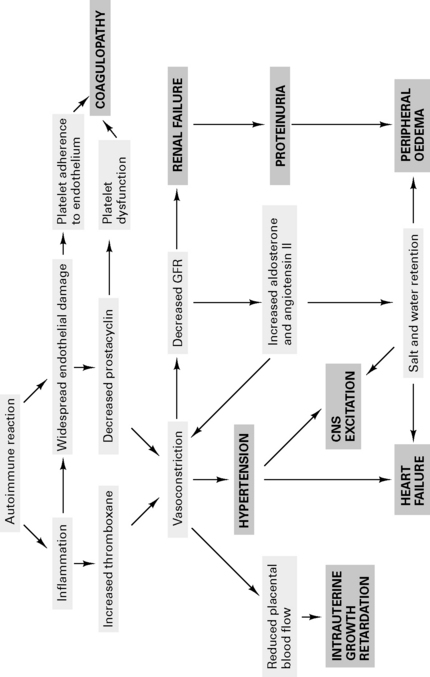

Turner J.A. Severe preeclampsia: anesthetic implications of the disease and its management. Am J Ther. 2009;16:284-288.

Maternal and fetal physiology

Maternal physiology

Cardiovascular

Respiratory

Gastrointestinal

Blood

Metabolism

Fetal physiology

Effect of anaesthesia and surgery on the fetus during LSCS

Effect of anaesthetic drugs on the fetus during LSCS

Fetal and maternal effects of epidurals

Cardiotocograph

Intraoperative Blood Cell Salvage in Obstetrics

National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2005(www.nice.org.uk/IPG144distributionlist)

Gaiser R.R. Old concepts applied to new problems: the fetus as a patient. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1998;11:251-253.

Heidemann B.H., McClure J.H. Changes in maternal physiology during pregnancy. BJA CEPD Rev. 2003;3:65-68.

NICE. Intraoperative blood cell salvage in obstetrics. Interventional Procedures Guideline, 144. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2005.