Chapter 17 Obstetric Procedures

Prenatal Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures

Prenatal Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures

ULTRASOUND

Obstetric transvaginal and transabdominal sonography plays a pivotal role in contemporary obstetric care, with ultrasonic imaging being done in about 70% of pregnancies in the United States today. Human data have shown no adverse fetal effects of ultrasound. Box 17-1 lists common abnormalities that may be identified prenatally with ultrasound.

Transvaginal Ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasound is useful in the first trimester of pregnancy because the close proximity of the intravaginal ultrasonic transducer allows for high-frequency scanning and thus better resolution of the pelvic organs and developing pregnancy than transabdominal imaging. Transvaginal ultrasound is commonly used in the first trimester to determine accurate dating of the pregnancy as well as fetal location and number. The nuchal translucency measurement (first-trimester screening), a sonographically derived assessment of the subcutaneous fluid collection at the level of the fetal neck, is a screening test for chromosomal and structural abnormalities that is performed between 11 and 14 weeks’ gestation, typically by a transabdominal but also a transvaginal approach (see Figure 7-2, pg 81). First-trimester vaginal ultrasound can also identify structural malformations. Transvaginal sonographic measurement of cervical length in the mid-trimester can be used to identify patients at risk for preterm delivery. The median length of the cervix at 24 to 28 weeks is 3.5 cm. Patients with a cervical length less than 2.0 cm are at significantly increased risk for preterm birth (threefold to fivefold). Finally, transvaginal ultrasonic imaging of the lower uterine segment in the second or third trimester allows for very precise identification of placental location in relation to the internal cervical os. In a patient with vaginal bleeding, excluding placenta previa is important in management.

Transabdominal Ultrasound

Ultrasonic visualization of aspects of fetal behavior (body movement, breathing) provides highly predictive information regarding fetal oxygenation and well-being. These aspects are combined to determine the biophysical profile (Box 17-2). The risk for fetal death within the week following a biophysical profile score of 8 or more is less than 1%.

AMNIOCENTESIS

Therapeutic Amniocentesis

The primary role of therapeutic amniocentesis has been in the management of polyhydramnios and twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Polyhydramnios, typically defined as a single deepest vertical pocket of amniotic fluid greater than 8 cm on ultrasound, can cause maternal respiratory embarrassment or premature labor. Excessive amniotic fluid volume may arise from lack of fetal swallowing or from excessive fetal urination. The latter condition occurs in the twin-twin transfusion syndrome (see Chapter 13). Serial amniocenteses to remove large volumes of excessive amniotic fluid from the sac of the recipient twin have been associated with improved perinatal outcome; however, recent data suggest that laser ablation of placental vascular connections between twin placentas with twin-twin transfusion syndrome is significantly better.

Cervical Cerclage

Cervical Cerclage

Cervical insufficiency or incompetence is defined as the inability of the uterine cervix to retain a pregnancy in the absence of contractions or labor (see Chapter 19). Cervical cerclage, a circumferential suture placed into the cervix, has been proposed as a surgical treatment for this condition. The cerclage is usually placed at 13 to 16 weeks.

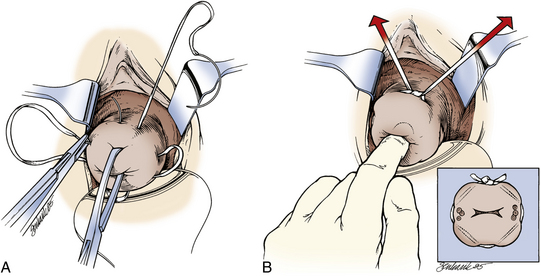

The most common procedure, McDonald’s cerclage, entails placement of a simple pursestring monofilament suture near the cervicovaginal junction (Figure 17-1). Shirodkar’s cerclage differs in that the stitch is placed as close to the internal os as possible. The bladder and rectum are dissected off the cervix, the woven tape-like suture is tied, and the mucosa is replaced over the knot. Transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage is rarely indicated and is reserved for select patients with previously failed vaginal cerclage, cervical hypoplasia, or a cervix severely scarred from prior lacerations or prior surgery. This type of cerclage entails dissection of the bladder from lower uterine segment through an abdominal incision. For transvaginal cerclage, the suture is typically removed before the onset of labor. For abdominal cerclage, cesarean delivery is performed. Patients must be counseled thoroughly regarding the risks associated with cerclage, which include bleeding, infection, iatrogenic rupture of amniotic membranes, and damage to adjacent organs (bladder and bowel).

Operative Delivery

Operative Delivery

OBSTETRIC FORCEPS

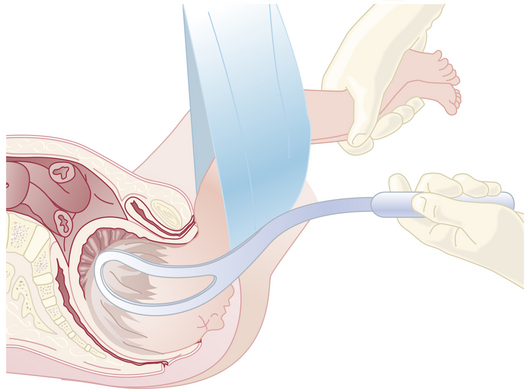

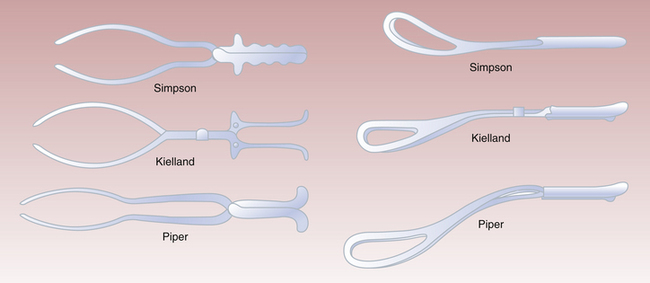

Forceps are instruments designed to provide traction and rotation of the fetal head when the expulsive efforts of the mother are insufficient to accomplish safe delivery of the fetus. Commonly used forceps are shown in Figure 17-2. There are two classes of obstetric forceps: classic forceps and specialized forceps. Forceps selection depends on the obstetric indication.

FIGURE 17-2 Types of obstetric forceps in use. Simpson forceps are an example of classic or standard forceps. Kielland forceps (for midforceps rotation) are an example of specialized forceps and are used infrequently. Piper forceps are used for breech delivery of the aftercoming head (see Figure 17-4).

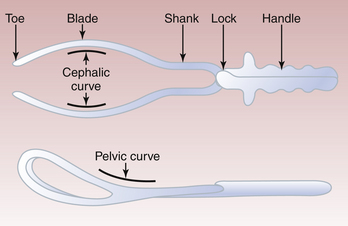

Classic or standard forceps are used to effect delivery by applying traction to the fetal skull. The components of each blade are illustrated in Figure 17-3. The blades have a cephalic curve designed to conform to the curvature of the fetal head. Simpson forceps (an example of classic or standard forceps) have a tapered cephalic curve that is designed to fit on a molded fetal head. The pelvic curve of classic forceps approximates the shape of the birth canal.

Indications

In general, there are four indications for an operative vaginal delivery:

Types of Forceps Operations

VACUUM EXTRACTION

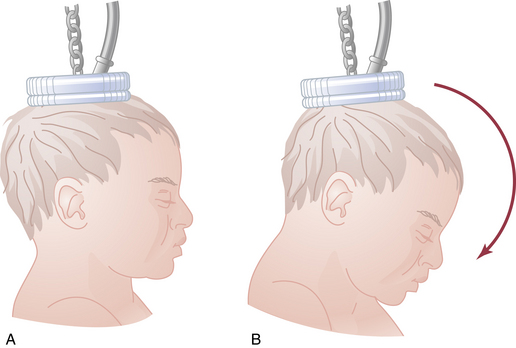

The vacuum extractor is an instrument that uses a suction cup that is applied to the fetal head. Because of relative ease of use compared with forceps, vacuum delivery has become more prevalent in the United States. After confirming that no maternal tissue is trapped between the cup and the fetal head, the vacuum seal is obtained using a suction pump. Traction is then applied using similar principles described previously for a forceps delivery. Flexion of the fetal head must be maintained to provide the smallest diameter to the maternal pelvis by placing the posterior edge of the suction cup 3 cm from the anterior fontanelle squarely over the sagittal suture. This is illustrated in Figure 17-5. With the aid of maternal pushing efforts, traction is applied parallel to the axis of the birth canal. Detachment of the suction cup from the fetal head during traction is termed a pop-off. If progress down the birth canal is not obtained with appropriate traction, or if two pop-offs occur, the procedure should be discontinued in favor of a cesarean delivery. The indications for vacuum delivery are the same as for forceps delivery.

CESAREAN DELIVERY

Types of Cesarean Deliveries

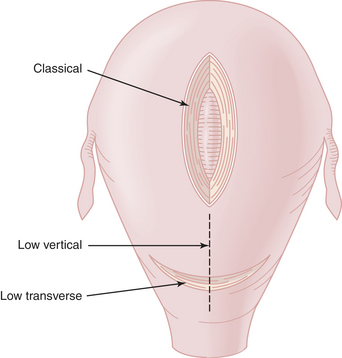

Cesarean deliveries are classified by the uterine incision (Figure 17-6), not the skin incision. In the low transverse cesarean delivery (LTCD), the uterine incision is made transversely in the lower uterine segment after establishing a bladder flap. The advantages of this approach include decreased rate of rupture of the scar in a subsequent pregnancy and a reduced risk for bleeding, peritonitis, paralytic ileus, and bowel adhesions.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cervical insufficiency. In ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 48. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2003.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 54. Obstet Gynecol, 104; 2004:203-212.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 77. Obstet Gynecol, 109; 2007:217-227.

Fox N.S., Chervenak F.A. Cervical cerclage: A review of the evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:58-65.