Chapter 24 Obstetric operations

INDUCTION OF LABOUR

Induction of labour may be required to ‘rescue’ the fetus from a potentially hazardous intra-uterine environment in late pregnancy for a variety of reasons, or because continuation of the pregnancy is dangerous to the expectant mother. Indications for induction of labour are listed in Table 24.1.

| Indication | Proportion of Inductions |

|---|---|

| Prolonged pregnancy (41 or more weeks) | 26% |

| Hypertensive disorders | 12% |

| Prelabour/prolonged rupture of membranes | 10% |

| Diabetes – pregestational and gestational | 7% |

| Intra-uterine growth restriction | 5% |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | 2% |

| Fetal death in utero (FDIU) | 1% |

| Blood group isoimmunization | 0.2% |

| Chorioamnionitis | 0.1% |

| Social induction | 16% |

| Others | 21% |

The method adopted depends on:

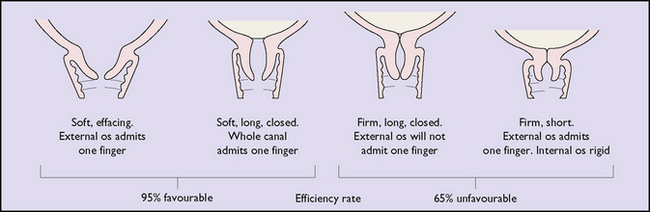

Fig. 24.1 The relationship between the condition of the cervix and success rate of surgical induction.

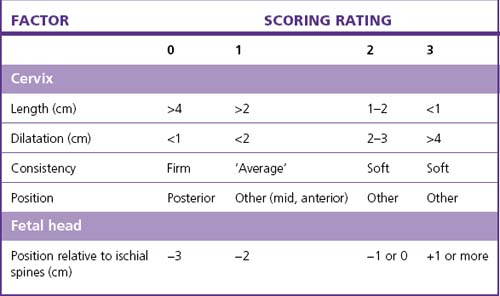

The highest rate of success, (i.e. that the induction is followed by a vaginal birth within 24 hours) occurs in a woman whose cervix is favourable and whose Bishop score is 5 or more (Table 24.2).

If the chances of success are evaluated as low, the doctor may recommend caesarean section.

Techniques of inducing labour

Induction of labour using drugs

Two agents are available: prostaglandins and oxytocin.

Prostaglandins

Three prostaglandins with different properties are used.

Surgical induction of labour (amniotomy)

The problems following amniotomy are:

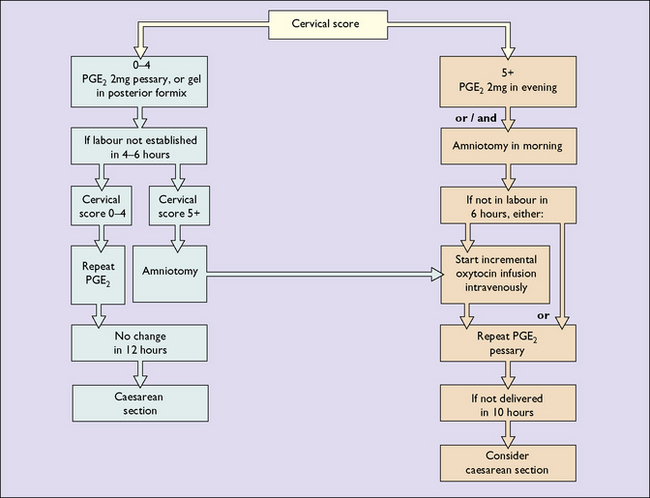

A suggested schema (flow chart) for the induction of labour is shown in Figure 24.2.

AUGMENTATION OF LABOUR

In cases where the quality of the uterine contractions is poor (see p. 174), their strength may be augmented by performing ARM and, if necessary, by setting up an incremental oxytocic infusion, or both.

INSTRUMENTAL DELIVERY

Obstetric forceps

Types of forceps delivery

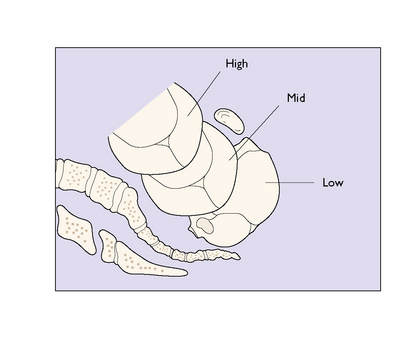

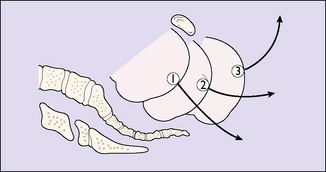

As shown in Figure 24.3, the station of the fetal head is used to describe the type of forceps delivery.

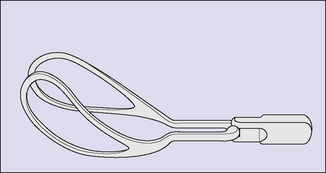

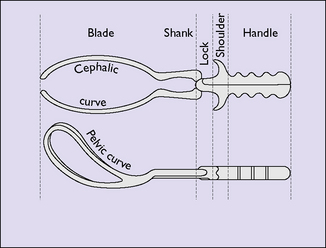

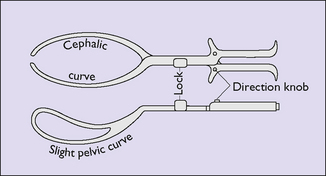

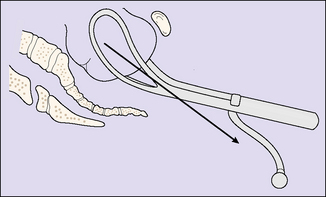

The short-shanked forceps is used for low or outlet forceps procedures (Fig. 24.4). The long-shanked forceps is used for midforceps delivery after manual rotation of the fetal head if it is arrested in the transverse diameter of the pelvis (Fig. 24.5). They are also suitable for low or outlet deliveries. Kjelland’s forceps has a sliding lock and can be used to rotate the fetal head and deliver it (see Fig. 24.6).

All forceps compress the fetal head to some extent and apply traction to effect the birth.

Technique of forceps delivery

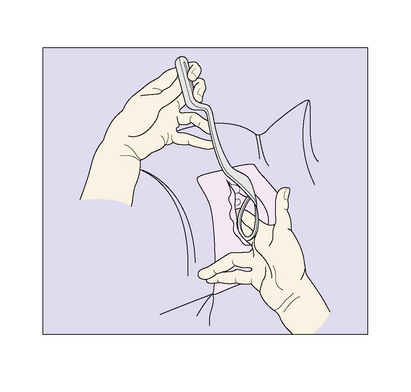

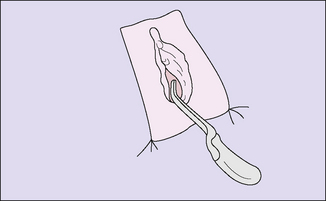

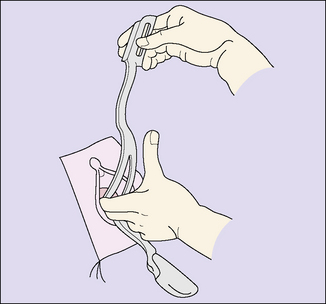

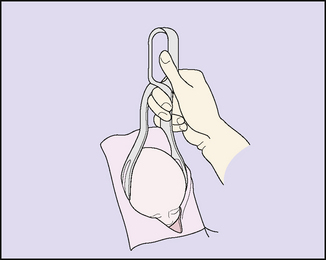

The technique of forceps delivery is shown in Figures 24.7–24.15.

Midforceps

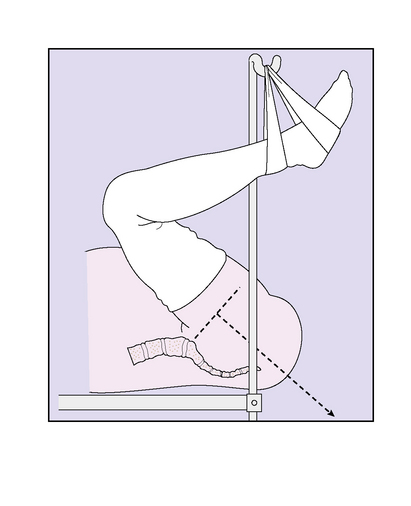

Because the head has to be pulled through the pelvic curve, the mother should be positioned correctly, with her legs in stirrups and her buttocks projecting over the end of the bed (see Fig. 24.11). This is because the pull required to deliver the baby has to be downwards initially and then curving upwards (see Fig. 24.12). Some obstetricians use the axis traction device, but skill is required to use it properly (see Fig. 24.13).

If the baby’s head is arrested in the transverse diameter of the midpelvis manual rotation may be attempted (see Fig. 24.14), followed by midforceps delivery. Alternatively, Kjelland’s forceps may be used or a caesarean section performed.

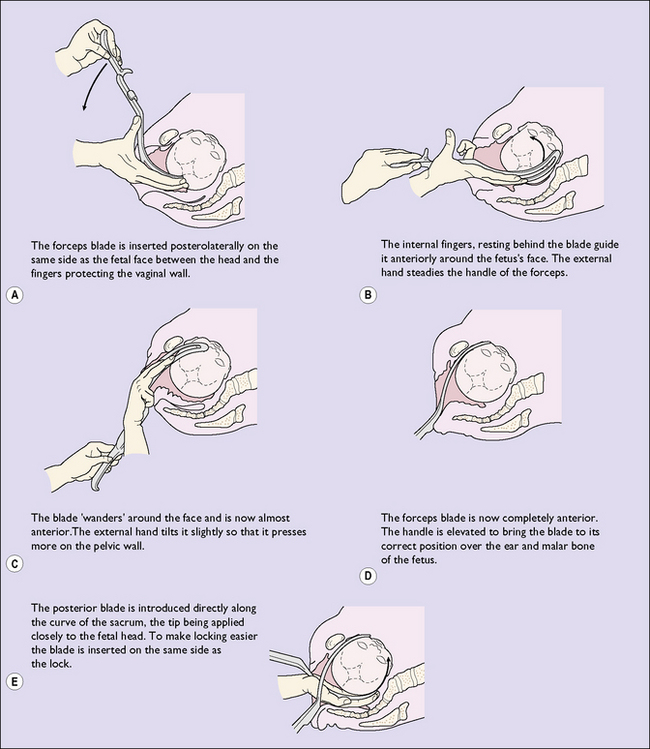

Kjelland’s forceps

The forceps is held in front of the woman’s vulva and positioned so that the dot on the shoulders of the instrument points to the side of the pelvis where the baby’s occiput lies. The remainder of the application of Kjelland’s forceps is shown in Figure 24.15. Usually a wide episiotomy is made, as perineal damage is almost inevitable. Alternative methods of delivery are vacuum extraction, manual rotation of the fetal head and forceps delivery, or caesarean section.

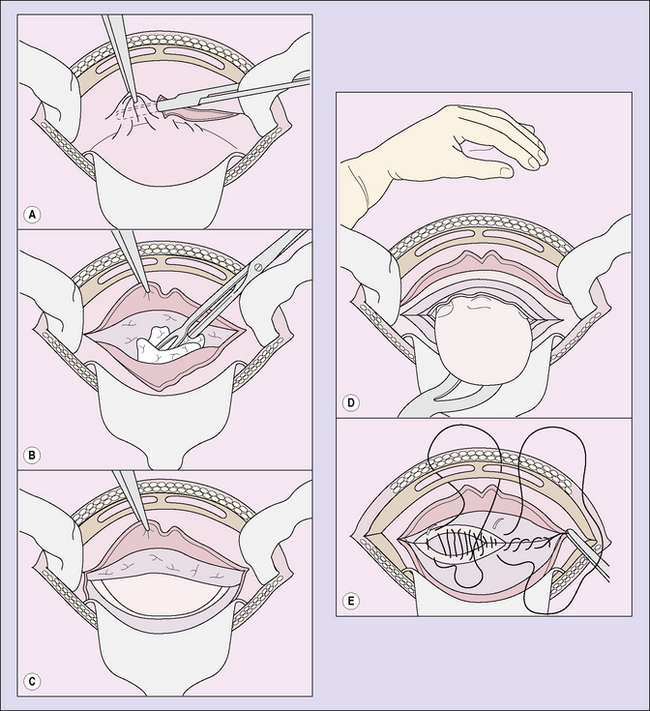

CAESAREAN SECTION

Indications for caesarean section

These have broadened in recent years and are listed in Box 24.1.

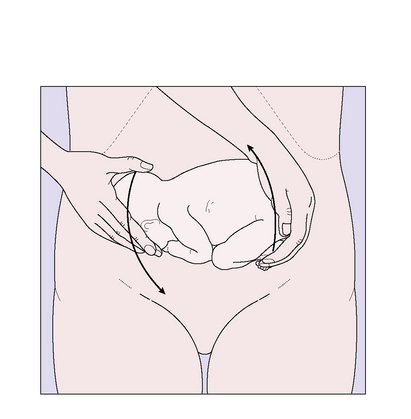

VERSION

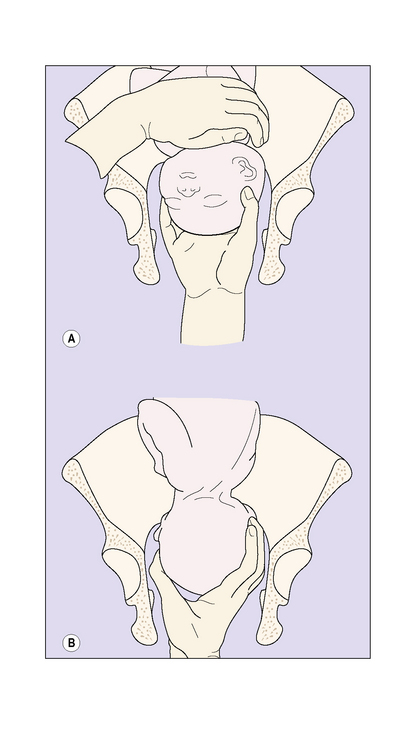

Some doctors give a tocolytic drug intravenously before the attempt. The version is performed gently. The breech is mobilized and the version attempted by lifting it with one hand and pushing the fetal head down with the other (Fig. 24.18). The fetal heart rate is either monitored continuously or every 2 minutes during, and for 30 minutes after, the version. If the fetal heart rate falls below 90 bpm during the version, the attempt is abandoned. Short-term bradycardia occurs in 20% but delivery by emergency caesarean section, because of persistent bradycardia, is required in only 0.2%.