Chapter 10 Obstetric Hemorrhage and Puerperal Sepsis

Antepartum Hemorrhage

Antepartum Hemorrhage

It is critical for the well-being of both the mother and the fetus that the patient who presents with third-trimester bleeding be evaluated and managed emergently. The differential diagnosis of third-trimester bleeding is listed in Box 10-1.

Abnormal Placentation

Abnormal Placentation

CLASSIFICATION

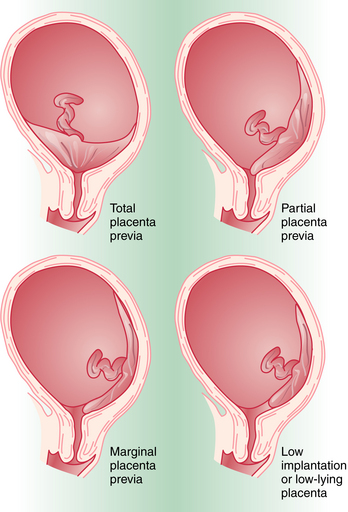

Placenta previa is classified according to the relationship of the placenta to the internal cervical os (Figure 10-1). Complete placenta previa implies that the placenta totally covers the cervical os. A complete placenta previa may be central, anterior, or posterior, depending on where the center of the placenta is located relative to the os. Partial placenta previa implies that the placenta partially covers the internal cervical os. A marginal placenta previa is one in which the edge of the placenta extends to the margin of the internal cervical os.

Abruptio Placentae

Abruptio Placentae

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Factors associated with an increased incidence of abruption are noted in Box 10-2. The most common of these risk factors is maternal hypertension, either chronic or as a result of preeclampsia. The risk for recurrent abruption is high: 10% after one abruption and 25% after two.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum Hemorrhage

ETIOLOGY

Most of the blood loss occurs from the myometrial spiral arterioles and decidual veins that previously supplied and drained the intervillous spaces of the placenta. As the contractions of the partially empty uterus cause placental separation, bleeding occurs and continues until the uterine musculature contracts around the blood vessels and acts as a physiologic-anatomic ligature. Failure of the uterus to contract after placental separation (uterine atony) leads to excessive placental site bleeding. Other causes of postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Box 10-3.

UTERINE ATONY

Most postpartum hemorrhages (75% to 80%) are due to uterine atony. The factors predisposing to postpartum uterine atony are listed in Box 10-4.

Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage and Obstetric Shock

Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage and Obstetric Shock

GENITAL TRACT TRAUMA

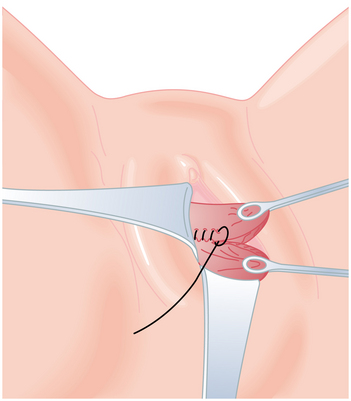

When postpartum hemorrhage is related to genital tract trauma, surgical intervention is necessary. When repairing genital tract lacerations, the first suture must be placed well above the apex of the laceration to incorporate any retracted bleeding arterioles into the ligature. Repair of vaginal lacerations requires good light and good exposure, and the tissues should be approximated without dead space. A running lock suture technique provides the best hemostasis (Figure 10-2). Cervical lacerations need not be sutured unless they are actively bleeding. Large, expanding hematomas of the genital tract require surgical evacuation of clots and a search for bleeding vessels that can be ligated, then packed for hemostasis. Stable hematomas can be observed and treated conservatively. A retroperitoneal hematoma generally begins in the pelvis. If the bleeding cannot be controlled from a vaginal approach, a laparotomy and bilateral hypogastric artery ligation may be necessary.

RETAINED PRODUCTS OF CONCEPTION

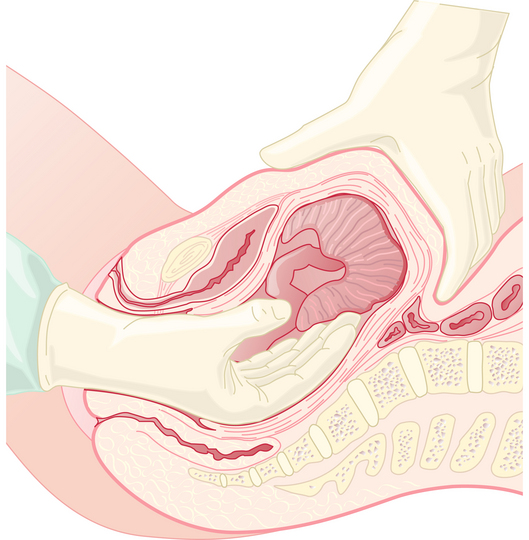

When the placenta cannot be delivered in the usual manner, manual removal is necessary (Figure 10-3). This should be performed urgently if bleeding is profuse. Otherwise, it is reasonable to delay 30 minutes to await spontaneous separation. General anesthesia may be required. Following manual removal of the placenta or placental remnants, the uterus should be scraped with a large curette.

COAGULOPATHY

When postpartum hemorrhage is associated with coagulopathy, the specific defect should be corrected by the infusion of blood products, as outlined in Table 10-1 and Box 10-5. Patients with thrombocytopenia require platelet concentrate infusions; those with von Willebrand’s disease require factor VIII concentrate or cryoprecipitate.

TABLE 10-1 BLOOD PRODUCTS USED TO CORRECT COAGULATION DEFECTS

| Blood Product | Volume (mL) in 1 Unit∗ | Effect of Transfusion |

|---|---|---|

| Platelet concentrate | 30-40 | Increases platelet count by about 20,000 to 25,000 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 15-25 | Supplies fibrinogen, factor VIII, and factor XIII (3-10 times more concentrated than the equivalent volume of fresh plasma) |

| Fresh-frozen plasma | 200 | Supplies all factors except platelets (1 g of fibrinogen) |

| Packed red blood cells | 200 | Raises hematocrit 3%-4% |

∗ Quantity obtained from 1 Unit (500 mL) of fresh whole blood.

BOX 10-5 Laboratory Evaluation of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation.

Puerperal Sepsis

Puerperal Sepsis

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Predisposing factors for the development of a puerperal genital tract infection are shown in Box 10-6.

Adesiyun A.G. Septic postpartum uterine inversion. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:943-945.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Postpartum hemorrhage. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1039-1047.

Castagnola D.E., Hoffman M.K., Carlson J., Flynn C. Necrotizing cervical and uterine infection in the postpartum period caused by group A streptococcus. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:533-535.

Dane B, Dane C: Maternal death after uterine rupture in an unscarred uterus: A case report. J Emerg Med 2008 Mar 31 (Epub ahead of print).

Maharaj D. Puerpueral pyrexia: A review. Parts 1 and 2. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:393-406.

Papathanasiou K., Tolikas A., Dovas D., et al. Ligation of internal iliac artery for severe obstetric and pelvic hemorrhage: 10 Year experience with 11 cases is a university hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;28:183-184.

Uterine Rupture

Uterine Rupture Fetal Bleeding

Fetal Bleeding Obstetric Shock

Obstetric Shock