Obstetric disorders

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Definitions

Oedema is defined as the development of pitting oedema or a weight gain in excess of 2.3 kg in a week. Oedema occurs in the limbs, particularly in the feet and ankles and in the fingers, or in the abdominal wall and face (Fig. 8.1). Oedema is very common in otherwise uncomplicated pregnancies, this is the least useful sign of hypertensive disease. It has therefore been dropped from many classifications.

Classification

The various types of hypertension are classified as follows:

• Gestational hypertension is characterized by the new onset of hypertension without any features of pre-eclampsia after 20 weeks of pregnancy or within the first 24 hours postpartum. Although by definition the blood pressure should return to normal by 12 weeks after pregnancy; it usually returns to normal within 10 days after delivery.

• Pre-eclampsia is the development of hypertension with proteinuria after the 20th week of gestation. It is commonly a disorder of primigravida women.

• Eclampsia is defined as the development of convulsions secondary to pre-eclampsia in the mother.

• Chronic hypertensive disease is the presence of hypertension that has been present before pregnancy and may be due to various pathological causes.

• Superimposed pre-eclampsia or eclampsia is the development of pre-eclampsia in a woman with chronic hypertensive disease or renal disease.

• Unclassified hypertension includes those cases of hypertension arising in pregnancy on a random basis where there is insufficient information for classification.

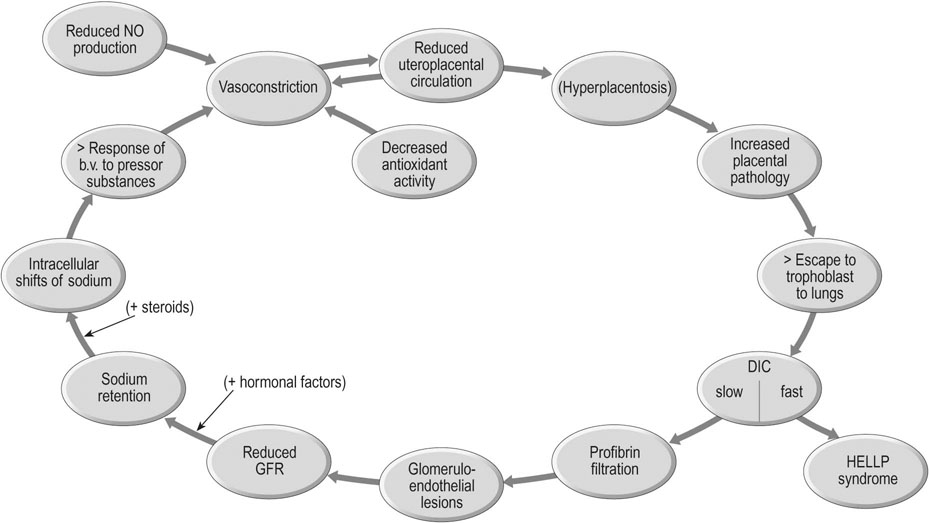

Pathogenesis and pathology of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

The pathophysiology of the condition, as outlined in Figure 8.2, is characterized by the effects of:

• Arteriolar vasoconstriction, particularly in the vascular bed of the uterus, placenta and kidneys.

Blood pressure is determined by cardiac output (stroke volume × heart rate) and peripheral vascular resistance. Cardiac output increases substantially in normal pregnancy, but blood pressure actually falls in the mid-trimester. Thus the most important regulatory factor is the loss of peripheral resistance that occurs in pregnancy. Without this effect, all pregnant women would presumably become hypertensive!

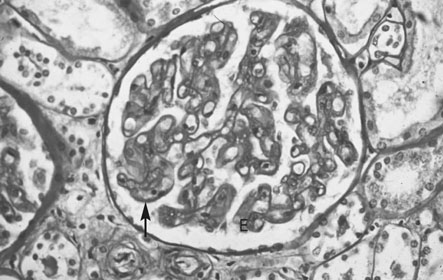

The renal lesion

The renal lesion is, histologically, the most specific feature of pre-eclampsia (Fig. 8.3). The features are:

• Swelling and proliferation of endothelial cells to such a point that the capillary vessels are obstructed.

• Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the intercapillary or mesangial cells.

• Fibrillary material (profibrin) deposition on the basement membrane and between and within the endothelial cells.

The characteristic appearance is therefore one of increased capillary cellularity and reduced vascularity. The lesion is found in 71% of primigravid women who develop pre-eclampsia but in only 29% of multiparous women. There is a much higher incidence of women with chronic renal disease in multiparous women.

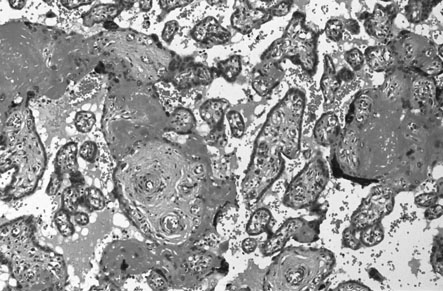

Placental pathology

Placental infarcts occur in normal pregnancy but are considerably more extensive in pre-eclampsia. The characteristic features in the placenta (Fig. 8.4) include:

• increased syncytial knots or sprouts

• proliferation of cytotrophoblast

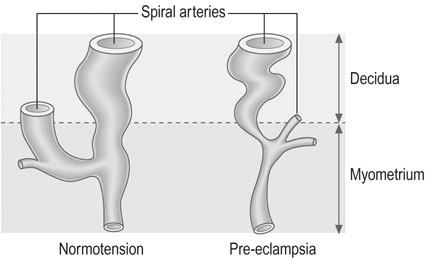

In the uteroplacental bed, the normal invasion of extravillous cytotrophoblast along the luminal surface of the maternal spiral arterioles does not occur beyond the deciduomyometrial junction and there is apparent constriction of the vessels between the radial artery and the decidual portion (Fig. 8.5). These changes result in reduced uteroplacental blood flow and results in placental hypoxia.

Management of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia

Maternal investigations

The most important investigations for monitoring the mother are:

• The 4-hourly measurement of blood pressure until such time that the blood pressure has returned to normal.

• Regular urine checks for proteinuria. Initially, screening is done with dipsticks or spot urinary protein/creatinine ratio but, once proteinuria is established, 24-hour urine samples should be collected. Values in excess of 0.3 g/L over 24 hours are abnormal.

Laboratory investigations

• Full blood count with particular reference to platelet count.

• Tests for renal and liver function.

• Uric acid measurements: a useful indicator of progression in the disease.

• Clotting studies where there is severe pre-eclampsia.

• Catecholamine measurements in the presence of severe hypertension, particularly where there is no proteinuria to rule out phaeochromocytoma.

Fetoplacental investigations

Measurements of fetal growth every 2 weeks. Parameters measured are fetal biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length.

Measurements of fetal growth every 2 weeks. Parameters measured are fetal biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length.

• Doppler flow studies up to twice weekly. The use of serial Doppler waveform measurements in the fetal umbilical artery and the maternal uterine artery makes it possible to assess increasing vascular resistance and hence impairment of uteroplacental blood flow typical of pre-eclampsia. In the second trimester poor diastolic flow in the uterine artery waveform warns of an increased risk of pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction later in pregnancy. In the third trimester, an increase in the systolic/diastole flow ratio in the fetal umbilical artery due to a progressive diminution of flow in diastole warns of worsening placental vascular disease. Absent or reverse flow in diastole indicates severe vessel disease, probable fetal compromise and delivery of the fetus must be considered if the cardiotocography (CTG) is abnormal.

• Antenatal CTG: Used in conjunction with Doppler assessment, the measurement of fetal heart rate in relation to uterine activity provides a useful, but by no means infallible indication of fetal wellbeing. The presence of episodes of fetal deceleration and the loss of baseline variability may indicate fetal hypoxia.

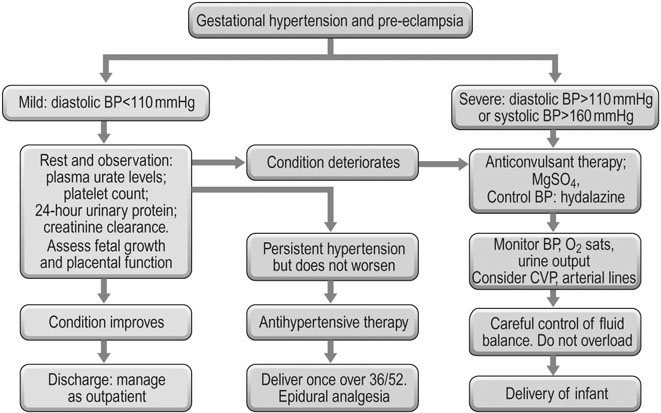

A summary of the various management strategies is shown in Figure 8.6. This flow diagram shows the various pathways of progression and their management. An initial presentation of mild hypertension may get better with conservative management or it may progress rapidly to the severe forms of pre-eclampsia and ultimately eclampsia.

Symptoms of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

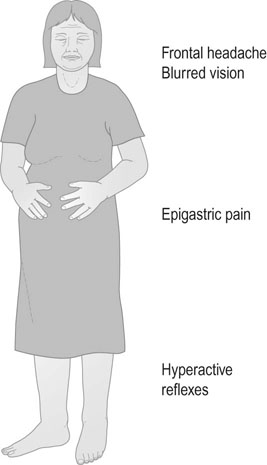

Pre-eclampsia is commonly an asymptomatic condition. However, there are symptoms that must not be overlooked and these include frontal headache, blurring of vision, sudden onset of vomiting and right epigastric pain. Of these symptoms, the most important is the development of epigastric pain – either during pregnancy or in the immediate puerperium (Fig. 8.7).

Induction of labour

If the decision has been made to proceed to delivery, the choice will rest with either the induction of labour or delivery by caesarean section. Antenatal steroids should be given for gestations of less than 34 weeks to minimize neonatal morbidity.

If the cervix is ripe, labour is induced by artificial rupture of membranes and oxytocin infusion (see Chapter 11).

Complications

Complications can be grouped as follows:

severe pre-eclampsia is associated with a fall in blood flow to various vital organs. If the mother is inadequately treated/the fetus is not delivered in a timely manner, complications include renal failure (raised creatinine/oliguria/anuria), hepatic failure, intrahepatic haemorrhage, seizures, DIC, adult RDS (ARDS), cerebral infarction, heart failure

severe pre-eclampsia is associated with a fall in blood flow to various vital organs. If the mother is inadequately treated/the fetus is not delivered in a timely manner, complications include renal failure (raised creatinine/oliguria/anuria), hepatic failure, intrahepatic haemorrhage, seizures, DIC, adult RDS (ARDS), cerebral infarction, heart failure

Management of eclampsia

The three basic guidelines for management of eclampsia are:

Control of fits

In the past various drugs were used to control the fits:

• Eclamptic seizures are usually self-limiting. Acute management is to ensure patient safety and protecting the airway

• Magnesium sulphate is the drug of choice for the control of fits thereafter. The drug is effective in suppressing convulsions and inhibiting muscular activity. It also reduces platelet aggregation and minimizes the effects of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Treatment is started with a bolus dose of 4 g given over 20 minutes as 20 mL of a 20% solution. Thereafter blood levels of magnesium are maintained by giving a maintenance dose of 1 g/h administered as a solution with 5 g/500 mL and run at 100 mL/h. The blood level of magnesium should only by measured if there is significant renal failure or seizures recur. The therapeutic range is 2–4 mmol/L. A level of more than 5 mmol/L causes loss of patellar reflexes and a value of more than 6 mmol/L causes respiratory depression. Magnesium sulphate can be given by intramuscular injection but the injection is often painful and sometimes leads to abscess formation. The preferred route is by intravenous administration.

Management after delivery

The following points of management should be observed:

• Maintain the patient in a quiet environment under constant observation.

• Maintain appropriate levels of sedation. If she has been treated with magnesium sulphate, continue the infusion for 24 hours after the last fit.

• Continue antihypertensive therapy until the blood pressure has returned to normal. This will usually involve transferring to oral medication and, although there is usually significant improvement after the first week, hypertension may persist for the next 6 weeks.

• Strict fluid balance charts should be kept and blood pressure and urine output observed on an hourly basis. Biochemical and haematological indices should be made on a daily basis until the values have stabilized or started to return to normal.

Although most mothers who have suffered from pre-eclampsia or eclampsia will completely recover and return to normal, it is important to review all such women at 6 weeks after delivery. If the hypertension or proteinuria persist at this stage, then they should be investigated for other factors such as underlying renal disease. Women should also be investigated for the possibility of an autoimmune, thrombophilic or antiphospholipid cause of her disease.

Antepartum haemorrhage

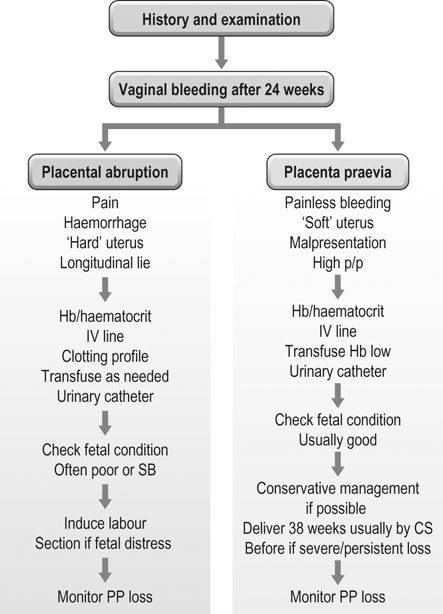

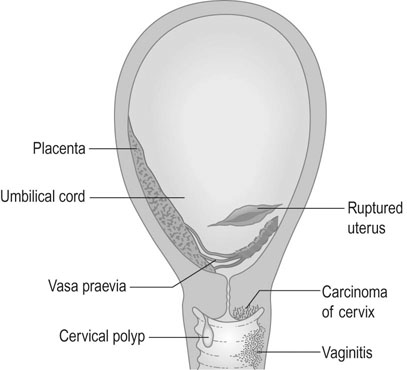

Vaginal bleeding may be due to:

• Haemorrhage from the placental site and uterus: placenta praevia, placental abruption, uterine rupture.

• Lesions of the lower genital tract: heavy show/onset of labour (bleed from cervical epithelium), cervical ectropion/carcinoma, cervicitis, polyps, vulval varices, trauma, infection.

Placenta praevia

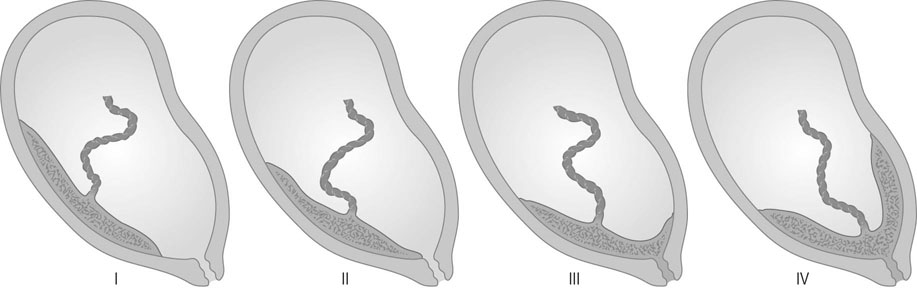

The placenta is said to be praevia when all or part of the placenta implants in the lower uterine segment and therefore lies beside or in front of the presenting part (Fig. 8.8).

Classification

There are numerous classifications of placenta praevia. The classification that affords the best anatomical description and clinical information is based on grades. Grade I being defined by the placenta encroaching on the lower segment but not on the internal cervical os; grade II when the placenta reaches the internal os; grade III when the placenta is covering the cervical os with some placental tissue also being in the upper segment; and grade IV when all the placenta is in the lower segment with the central portion close to the cervical os (see Fig. 8.8). Women with a grade I or grade II placenta on the anterior wall of the uterus will commonly achieve a normal vaginal delivery without excess blood loss. A posterior grade II placenta praevia where the placental mass in front of the maternal sacrum prevents the descent of the fetal head into the pelvis, along with a grade III and IV placenta praevia will require delivery by caesarean section, either urgently if labour or significant bleeding commences preterm, or electively at term.

Diagnosis

Abdominal examination

• Displacement of the presenting part: The finding of painless vaginal bleeding with a high central presenting part, a transverse or an oblique lie strongly suggests the possibility of placenta praevia. Although a speculum examination may be undertaken by a skilled obstetrician in these cases to check for the site of the bleeding, a digital vaginal examination must not be undertaken until an ultrasound has been performed. A digital examination may disrupt the placenta and cause excessive bleeding.

• Normal uterine tone: Unlike with abruption, the uterine muscle tone is usually normal and the fetal parts are easy to palpate.

Diagnostic procedures

• Ultrasound scanning: Transabdominal and, for posterior placentas, transvaginal ultrasound is used to localize the placenta where there is a suggestion of placenta praevia. Anteriorly, the bladder provides an important landmark for the lower segment and diagnosis is more accurate. When the placenta is on the posterior wall, the sacral promontory is used to define the lower segment, however if this cannot be seen with transabdominal scanning, a transvaginal scan is used to determine the distance from the cervical os to the lower margin of the placenta. Localization of the placental site in early pregnancy may result in inaccurate diagnosis, as development of the lower segment will lead to an apparent upward displacement of the placenta by 30 weeks.

• Magnetic resonance imaging: This is used when the placenta is implanted on the lower uterine segment over an old caesarean scar. It may help to determine if the placental tissue has migrated through the scar (placenta percreta) or even into the bladder tissue.

Management

• When there is serious doubt about the diagnosis due to inadequate ultrasound facilities and labour appears to have commenced. First the examination has to be through the fornices to feel whether the presenting part can be felt easily. If there is difficulty in palapating or a boggy mass is felt then it is likely to be placenta. If the presenting part is felt via the fornices, careful digital examination can be done via the cervix with the intention of rupturing the membranes. Blood should be in the theatre and anaesthetist and theatre staff ready for caesarean section should there be a torrential haemorrhage.

It is, in fact, often difficult to establish a diagnosis of placentae praevia by vaginal examination where the placenta is lateral, and there is a serious risk of precipitating massive haemorrhage if the placenta is central. If the placenta is lateral, then it may be possible to rupture the membranes and allow spontaneous vaginal delivery if the head of the baby is in the pelvis.

Abruptio placentae

Clinical types and presentation

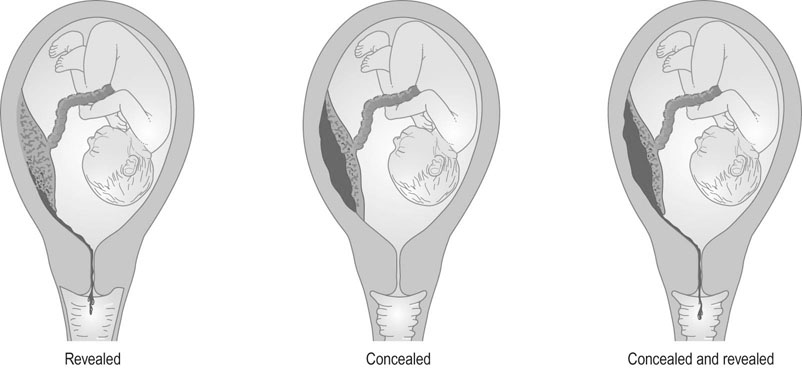

Although three types of abruption have been described, i.e. revealed, concealed or mixed (Fig. 8.9), this classification is not clinically helpful. Commonly the classification is made after delivery when the concealed clot is discovered.

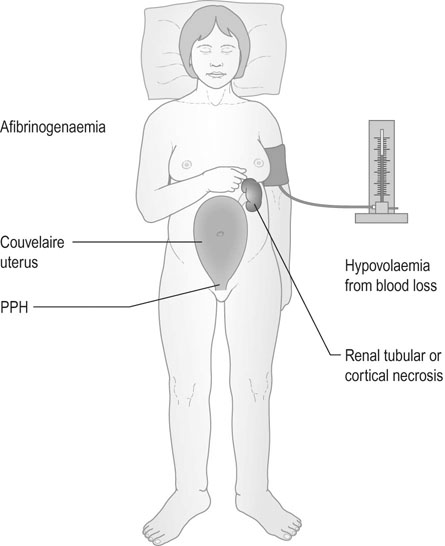

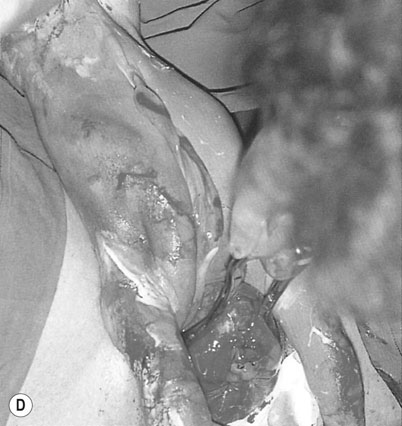

Haemorrhage

In some severe cases, haemorrhage penetrates through the uterine wall and the uterus appears bruised. This is described as a Couvelaire uterus. On clinical examination the uterus will be tense and hard and the uterine fundus will be higher than is normal for the gestational age. With this severe form of abruption the mother will often be in labour and in approximately 30% of cases the fetal heart sounds will be absent and the fetus will be stillborn.

Management

The patient must be admitted to hospital and the diagnosis established on the basis of the history, examination findings (Fig. 8.10) and ultrasound findings. In preterm pregnancy, mild cases (mother stable and CTG normal) may be treated conservatively. An ultrasound examination should be used to assess fetal growth and wellbeing, and the placental site should be localized to confirm the diagnosis. If the fetus is preterm, the aim of management is to prolong the pregnancy if the maternal and fetal condition allow. Conditions that are associated with abruption, e.g. hypertension, should be managed appropriately. If the haemorrhage is severe, resuscitation of the mother is the first prerequisite, following which fetal condition can be addressed.

Multiple pregnancy

Types of twinning and determination of chorionicity

Any multiple pregnancy may result from the release of one or more ova at the time of ovulation.

Monozygotic multiple pregnancy

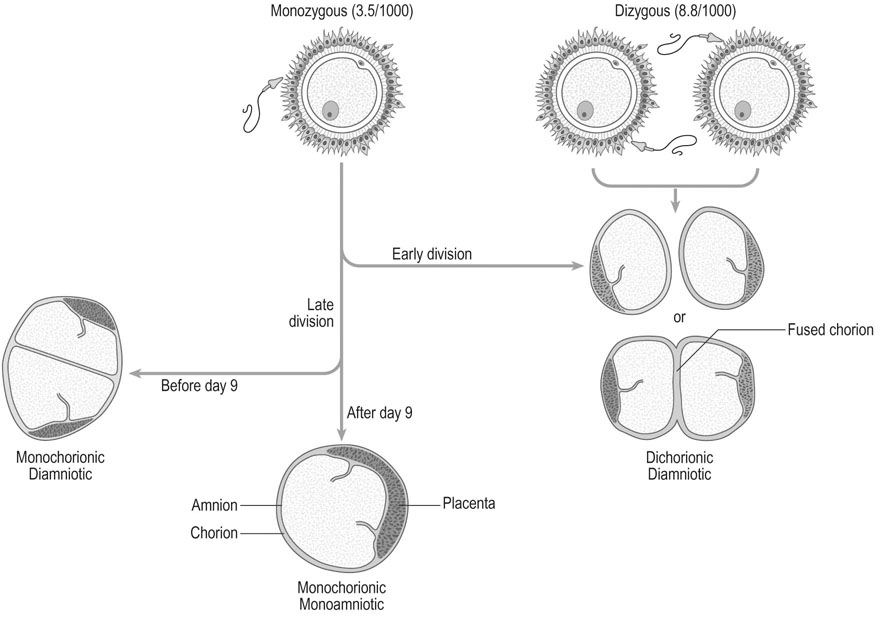

If a single ova results in a multiple pregnancy the embryos are called monozygotic, with alternative names of uniovular and identical. The rate of monozygotic twins is approximately 1/280 pregnancies, is unaffected by race, and is increased by reproductive technology for unknown reasons. The zygote divides sometime after conception (Fig. 8.13). If the split postconceptually occurs at:

0–4 days there will be 2 embryos, 2 amnions, 2 chorions (as for dizygotic twins): 25–30%

4–8 days there will be 2 embryos, 2 amnions, 1 chorion: 65–70%

9–12 days there will be 2 embryos, 1 amnion and 1 chorion: 1–2%

13+ days there will be conjoint twins, 1 amnion and 1 chorion: <1%

Given that the embryo splits under some unknown influence, monozygotic multiple pregnancy is considered to be an anomaly of reproduction. Occasionally the embryo splits into 3 resulting in monozygotic triplets. In the case of triplets the splitting may occur at the same time or sequentially resulting in conjoint twins with a separate singleton pregnancy all within one chorion!

Dizygotic twins

These come from the separate fertilization of separate ova by different sperm. In 50% of such pregnancies the fetuses are male–female, with 25% being male–male and 25% being female–female. All will have either 2 separate placentas on ultrasound or a single placenta with a thick membrane with a ‘twin peak’ sign. The presence of lambda (chorion in between membranes) or T (absence of chorion in between membranes) sign at the site of membrane insertion of the placenta in the first trimester has been valuable to determine whether they are monochorionic diamniotic or dichrionic diamniotic twins (Fig. 8.14). Monochorionic diamniotic twins may have placental vascular anastomosis and may give rise to complications of twin to twin transfusion and its consequent sequelae.

The rate of dizygotic twins varies with:

• Familial factors: The familial tendency is apparent in dizygotic twinning, but this appears to be on the maternal side only. In a study of records at Salt Lake City, the twinning rates of women who were themselves dizygotic twins was 17.1/1000 maternities compared with 11.6/1000 maternities for the general population, but the rate for males who were themselves dizygotic twins was only 7.9/1000 maternities.

• Parity and maternal age: Studies in Aberdeen have shown that the rate increases from 10.4/1000 in primigravidae to 15.3/1000 in the para 4+ group. There is also a small increase in twinning in older mothers.

• Ovulation induction: Multiple pregnancy is common following the use of drugs to induce ovulation. It is important to note that the use of gonadotrophin therapy can result in twins, triplets or even higher order pregnancies. To some degree this can be avoided by monitoring ovarian follicular development and withholding the injection of human chorionic gonadotrophin if excessive numbers of follicles develop. The use of fertility drugs accounts for 10–15% of all multiple pregnancies and has therefore significantly altered the incidence of multiple pregnancy.

As mentioned earlier the risk of multiple pregnancy as a result of IVF has decreased with the limitation of the number of embryos transferred.

Complications of twin pregnancy

It is thus to be expected that the increased strain put on the system by carrying more than one fetus will result in a higher incidence of complications (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

Risks associated with twin pregnancies

| Obstetric complication | Risk* |

| Anaemia | x2 |

| Pre-eclampsia | x3 |

| Eclampsia | x4 |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | x2 |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | x2 |

| Fetal growth restriction | x3 |

| Preterm delivery | x6 |

| Caesarean section | x2 |

Complications unrelated to zygosity

Preterm labour

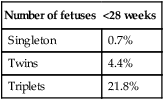

The occurrence of preterm labour is the most important complication of twin pregnancy (Table 8.2). The onset of labour before 37 weeks gestation occurs in over 40% of twin pregnancies. The phenomenon appears to be associated with overdistension of the uterus associated with the presence of more than one fetus and is further increased if the amniotic fluid volume is increased.

Table 8.2

Rates of preterm delivery by fetal number

| Number of fetuses | <28 weeks |

| Singleton | 0.7% |

| Twins | 4.4% |

| Triplets | 21.8% |

Management of labour and delivery

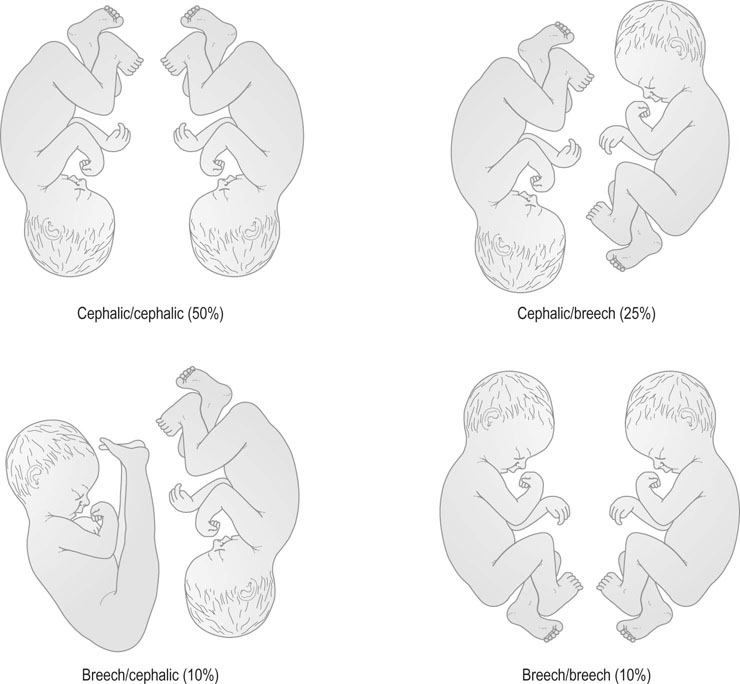

Presentation at delivery

There are a number of permutations for presentation in twin pregnancy at delivery, which are partly influenced by the management of the second twin. Rounded-up figures for these presentations are shown in Figure 8.16.

Prolonged pregnancy

The term ‘postmaturity’ refers to the condition of the infant and has characteristic features (Box 8.1). These are all indicators of intrauterine malnutrition and may therefore occur at any stage of the pregnancy if there is placental dysfunction. Postmaturity is often associated with oligohydramnios, an increased incidence of meconium in the amniotic fluid and an increased risk of intrauterine aspiration of meconium-stained fluid into the fetal lungs. It is found in 2% of pregnancies at 41 weeks and up to 5% of pregnancies at 42 weeks. Unexpected stillbirth in such prolonged pregnancies is a particular tragedy for the mother, and she and her carer will always live with the knowledge that the child would almost certainly have survived had action to deliver the baby been taken earlier.

Breech presentation

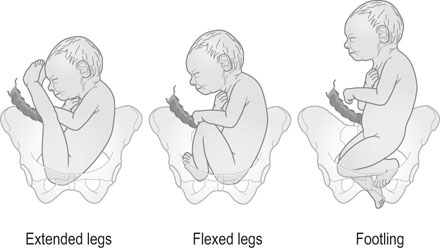

Types of breech presentation

The breech may present in one of three ways (Fig. 8.17):

• Frank breech: The legs lie extended along the fetal trunk and are flexed at the hips and extended at the knees. The buttocks will present at the pelvic inlet. This presentation is also known as an extended breech.

• Flexed breech: The legs are flexed at the hips and the knees with the fetus sitting on its legs so that both feet present to the pelvic inlet.

• Knee or footling presentation: one or both of the lower limbs of the fetus are flexed and breech of the baby is above the maternal pelvis so that a part of the fetal lower limb (usually feet) descends through the cervix into the vagina.

The position of the breech is defined using the fetal sacrum as the denominator. At the onset of labour the breech enters the brim of the true pelvis with the bitrochanteric diameter (less than 10 cm) being the diameter of descent. This diameter is slightly smaller than the biparietal diameter in the full-term fetus. The type of breech presentation has a significant impact on the risk of vaginal breech delivery. The more irregular the presenting part, the greater is the risk of a prolapsed cord or limb. A foot pressing into the vagina below the cervix may stimulate the mother to bear down before the cervix is fully dilated and thus lead to entrapment of the head (Fig. 8.17).

Causation and hazards of breech presentation

There is also evidence to suggest that persistent breech presentation may be associated with the inability of the fetus to kick itself around from breech to vertex and that there may therefore be some neurological impairment of the lower limbs (Box 8.2).

Delivery by the breech carries some specific hazards to the infant as compared with normal vertex presentation, particularly in preterm infants and in infants with a birth weight in excess of 4 kg:

• There is an increased risk of cord compression and cord prolapse because of the irregular nature of the presenting part. This is particularly the case where the legs are flexed or there is a footling presentation.

• Entrapment of the head behind the cervix is a particular risk with the preterm infant, in whom the bitrochanteric diameter of the breech is significantly smaller than the biparietal diameter of the head. This means that the trunk may deliver through an incompletely dilated cervix, resulting in entrapment of the larger head. If the delivery is significantly delayed, the child may be asphyxiated and either die or suffer brain damage.

• The fetal skull does not have time to mould during delivery and therefore, in both preterm and term infants, there is a significant risk of intracranial haemorrhage.

• Trauma to viscera may occur during the delivery process, with rupture of the spleen or gut if the obstetrician handles the fetal abdomen.

Management

Antenatal management

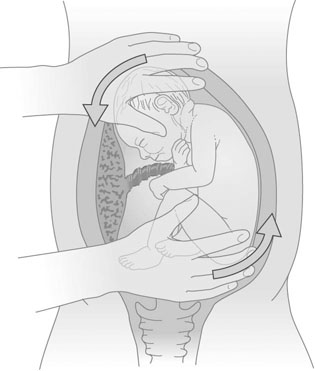

External cephalic version (ECV)

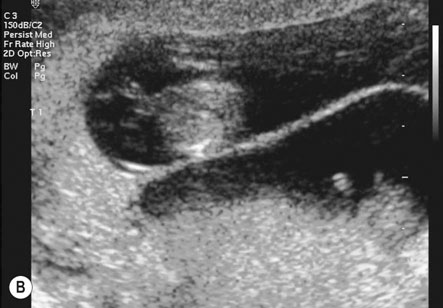

Technique

The mother rests supine with the upper body slightly tilted down. The presentation and placental position are confirmed by ultrasound. The fetal heart rate is checked preferably with a small strip of CTG. A tocolytic agent (oral nifedipine or IM terbutaline) is given to relax the uterus as this improves the success rate (Fig. 8.18).

Method of delivery

Vaginal breech delivery

Technique

When the cervix is fully dilated, and the presenting part is low in the pelvis the mother is encouraged to bear down with her contractions until the fetal buttocks and anus come on view (Fig. 8.19). To minimize soft tissue resistance, an episiotomy should be considered under either local or epidural anaesthesia, unless the pelvic floor is already lax and offers little resistance. The legs are then lifted out of the vagina by flexing the fetal hip and knees. The baby is then expelled with maternal pushing with the obstetrician only touching the upper thighs and then only to ensure that the fetal back remains anterior. Once the trunk has delivered as far as the scapula, the arms can usually be easily delivered one at a time by sliding the fingers over the shoulder and sweeping them downwards across the fetal head. If the arms are extended and pose difficulty in delivering, the body of the fetus is rotated by holding the baby’s pelvis till the posterior arm comes under the symphysis pubis. The arm can then be delivered by flexing at the elbow and the shoulders. The procedure is repeated by rotating the body to deliver the other arm (Loveset’s manouvre). The trunk is then allowed to remain suspended for about 30 seconds to allow the head to enter the pelvis and then the legs are grasped and swung upwards through an arc of 180° until the child’s mouth comes into view. At this point the baby may spontaneously deliver, however a number of techniques including the use of forceps can be used to ensure the safe delivery of the head.

The cord is then clamped and divided and the third stage is completed in the usual way.

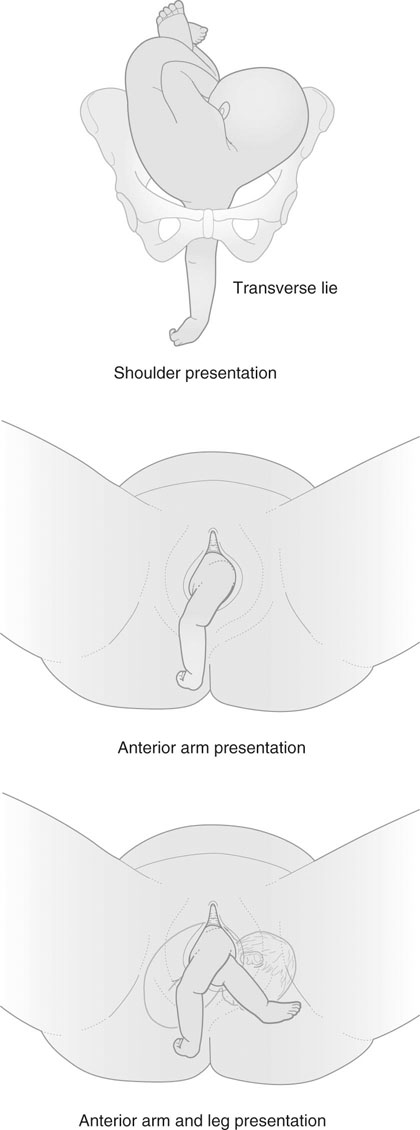

Unstable lie, transverse lie and shoulder presentation

Management

• Keep the mother in hospital and await spontaneous correction of the lie, or correct the lie as labour starts spontaneously.

• Stabilizing induction, performed by first correcting the lie to a cephalic presentation, and rupturing the membranes as the head approaches the pelvic brim assisted by gentle suprapubic pressure, followed by oxytocin infusion.

If there are any other complicating factors, it may on occasions be advisable to deliver the mother at term by planned elective section (Box 8.3).