Chapter 12 Obstetric Complications

PRETERM LABOR, PROM, IUGR, POSTTERM PREGNANCY, AND IUFD

Preterm Labor

Preterm Labor

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

The estimated causes of preterm birth are listed in Table 12-1. Private patients have a much higher proportion of spontaneous preterm labor, whereas black patients in public institutions have a higher proportion of deliveries due to PPROM.

| Cause | Estimated Percentage of Preterm Births |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous preterm labor | 35-37 |

| Multiple pregnancies∗ | 12-15 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) | 12-15 |

| Pregnancy-associated hypertension | 12-14 |

| Cervical incompetence or uterine anomalies | 12-14 |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 5-6 |

| Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) | 4-6 |

∗ Increasing proportion due to advancing maternal age and assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

PREVENTION

Four potential pathways leading to preterm delivery have been identified:

UTERINE TOCOLYTIC THERAPY

It is assumed that physiologic events leading to the initiation of labor also occur in preterm labor. The pharmacologic agents presently being used all seem to inhibit the availability of calcium ions, but they may also exert a number of other effects. The agents currently used and their dosages are presented in Box 12-1.

BOX 12-1 Uterine Tocolytic Agents

Magnesium Sulfate

Magnesium Sulfate

Although magnesium levels required for tocolysis have not been critically evaluated, it appears that the levels needed may be higher than those required for prevention of eclampsia. Levels from 5.5 to 7.0 mg/dL appear to be appropriate. These can be achieved using the dosage regimen outlined in Box 12-1. After the loading dose is given, a continuous infusion is maintained, and plasma levels should be determined until therapeutic levels are reached. The drug should be continued at therapeutic levels until contractions cease unless the labor progresses. Because magnesium is excreted by the kidneys, adjustments must be made in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance. Once successful tocolysis has been achieved, the infusion is continued for at least 12 hours, and then the infusion rate is weaned over 2 to 4 hours and then discontinued. In high-risk patients (advanced cervical dilation or continued labor in very-low-birth-weight cases), the infusion can be continued until the fetus has been exposed to glucocorticoids to enhance lung maturity.

Premature Rupture of the Membranes

Premature Rupture of the Membranes

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Two types of fetal growth restriction have been described: symmetrical and asymmetrical. In fetuses with symmetrical growth restriction, growth of both the head and the body is inadequate. The head-to-abdominal circumference ratio may be normal, but the absolute growth rate is decreased. Symmetrical growth restriction is most commonly seen in association with intrauterine infections or congenital fetal anomalies. When asymmetrical growth restriction occurs, usually late in pregnancy, the brain is preferentially spared at the expense of abdominal viscera. As a result, the head size is proportionally larger than the abdominal size. The liver and fetal pancreas undergo the most dramatic anatomic and biochemical changes, and these changes are now thought to play an important role in programming the fetus for a greater risk for obesity and diabetes later in life (see Chapter 1).

DIAGNOSIS

Growth restriction may go undiagnosed unless the obstetrician establishes the correct gestational age of the fetus (Box 12-2), identifies high-risk factors from the obstetric database, and serially assesses fetal growth by fundal height or ultrasonography. Fetal or neonatal IUGR is usually defined as weight at or below the 10th percentile for gestational age.

BOX 12-2 Factors Evaluated in Dating a Pregnancy

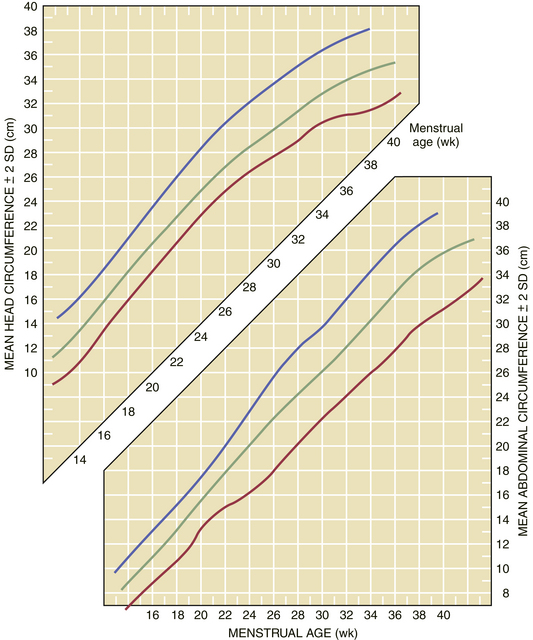

At present, a number of sonographic parameters are used to diagnose IUGR: (1) biparietal diameter (BPD), (2) head circumference, (3) abdominal circumference (Figure 12-1), (4) head-to-abdominal circumference ratio, (5) femoral length, (6) femoral length–to–abdominal circumference ratio, (7) amniotic fluid volume, (8) calculated fetal weight, and (9) umbilical and uterine artery Doppler. Of these, the abdominal circumference is the single most effective parameter for predicting fetal weight because it is reduced in both symmetrical and asymmetrical IUGR. Most formulas for estimating fetal weight incorporate two or more parameters to reduce the variance of measurements.

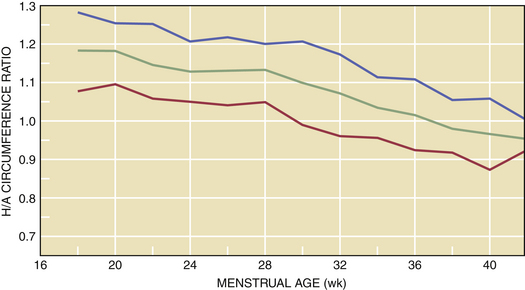

During advancing gestation, the head circumference remains greater than the abdominal circumference until about 34 weeks, at which point the ratio approaches 1 (Figure 12-2). After 34 weeks, the normal pregnancy is associated with an abdominal circumference that is greater than the head circumference. When asymmetrical growth restriction occurs, usually in the third trimester, the BPD is essentially normal, whereas the ratio of head to abdominal circumference is abnormal. With symmetrical growth restriction, the head-to-abdominal circumference ratio may be normal, but the absolute growth rate is decreased, and estimated fetal weight is reduced.

MANAGEMENT

Antepartum

Fetuses clinically suspected of IUGR could be approached as follows:

Doppler-derived umbilical artery systolic-to-diastolic ratios are abnormal in IUGR fetuses. Fetuses with growth restriction tend to have increased resistance to flow and to demonstrate low, absent, or reversed diastolic flow This noninvasive technique can be used to evaluate high-risk patients and may help in the timing of delivery when used in conjunction with the modified biophysical profile (see Chapter 7 for more information about Doppler assessment of fetal well-being).

PROGNOSIS

The long-term prognosis for infants with IUGR must be assessed according to the varied etiologies of the growth restriction. If infants with chromosomal abnormalities, autoimmune disease, congenital anomalies, and infection are excluded, the outlook for these newborns is generally good. However, the IUGR infant is at greater risk for adult-onset diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (see Chapter 1).

Intrauterine Fetal Demise

Intrauterine Fetal Demise

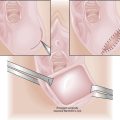

FOLLOW-UP

A search should be undertaken to determine the cause of the intrauterine death. TORCH (see Table 7-1) and parvovirus studies and cultures for Listeria are indicated. In addition, all women with a fetal demise should be tested for the presence of anticardiolipin antibodies. Testing for the hereditary thrombophilias should also be considered. If congenital abnormalities are detected, fetal chromosomal studies and total body radiographs should be done, in addition to a complete autopsy. The autopsy report, when available, must be discussed in detail with both parents. In a stillborn fetus, the best tissue for a chromosomal analysis is the fascia lata, obtained from the lateral aspect of the thigh. The tissue can be stored in saline or Hanks’ solution. A significant number of cases of IUFD are the result of fetomaternal hemorrhage, which can be detected by identifying fetal erythrocytes in maternal blood (Kleihauer-Betke test).

Subsequent pregnancies in a woman with a history of IUFD must be managed as high-risk cases.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. ACOG Committee Opinion No 273. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:871-873.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Evaluation of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. ACOG Committee Opinion No 383. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:963-966.

Caritis S. Adverse effects of tocolytic therapy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(Suppl 1):74-88.

Nardin JM, Carroli G, Alfirevic Z: Combination of tocolytic agents for inhibiting preterm labour (Protocol). Most recent amendment: 22 July 2006. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com.

National Center for Health Statistics: 2004 Final Nationality Data. March of Dimes Perinatal Data Center, 2007. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.com/peristats.

Tucker J., McGuire W. Epidemiology of preterm birth. BMJ. 2004;329:675-678.

Tests of Pulmonary Maturity

Tests of Pulmonary Maturity Surfactant Therapy

Surfactant Therapy

Postterm Pregnancy

Postterm Pregnancy