Chapter 27 OBESITY SURGERY

DEFINITIONS OF OBESITY

The increasing prevalence of obesity is a worldwide phenomenon and it is a disease with protean adverse physical, social and psychological effects. The classification of obesity defines the relationship between a person’s height and weight, the body mass index (BMI) to stratify patients according to their risk of obesity-related medical conditions (Table 27.1).

| BMI (kg/m2) | Obesity class | |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | – |

| Normal | 18.5–24.9 | – |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | – |

| Obesity | 30.0–34.9 | I |

| 35.0–39.9 | II | |

| Extreme obesity | 40.0+ | III |

* The term ‘morbid obesity’ relates to BMI 35.0–39.9 with medical comorbidities or BMI 40 and above.

TREATMENT OF OBESITY

Having surgery entails taking on some risks, so it is obvious that this is not a treatment that can be applied liberally. The effects of any operation, both positive and negative, may be permanent and some complications may develop insidiously many years later and, therefore, may not be related to the operation. Current, generally accepted criteria for selecting patients for surgery are listed in Table 27.2.

| Body weight | BMI >40 |

| BMI 35–39.9 with medical comorbidities | |

| No endocrine cause | |

| Resistant obesity | Obesity present >5 years |

| Multiple failed non-surgical attempts | |

| Psychological profile | No alcohol or drug use |

| No or controlled psychiatric conditions | |

| Understanding of surgery and commitment to follow-up |

Weight-loss surgery

Obesity is a chronic, probably life-long disease and, therefore, the current surgical solutions are designed to cause permanent alterations to gastrointestinal physiology. These physiological alterations, while necessary for the maintenance of weight-loss, may become disordered and lead to the patient presenting for medical or surgical care. There are a range of bariatric surgical procedures currently undertaken, and a number of historical procedures that remain of interest due to the large number of patients who have undergone them in the past. Thankfully there is sufficient homology between all of the historic and current procedures to allow them to be grouped into categories when discussing them. Complications following surgery may be related to weight loss itself (e.g. gallstones), anatomic changes (e.g. vomiting, obstruction) or altered nutritional status (e.g. decreased intake, decreased absorption or gastrointestinal losses). Most of the subtle nutritional complications that can arise after this type of surgery are beyond the scope of this chapter and will not be discussed.

BARIATRIC OPERATIONS

Operations for morbid obesity are grouped into:

These terms are historically based and fail to take into account the often complex variations between individual operations; they also inadequately explain the mechanisms by which the procedures work.

Gastroplasty

Adjustable gastroplasty

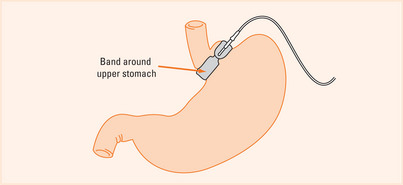

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) is a procedure that has been responsible for the increase in uptake of bariatric surgery in many countries outside the USA. The band is placed just below the cardia, so that the volume of stomach above the band stoma is a couple of millilitres in size only (Figure 27.1).

A more difficult cause of vomiting or reflux is stoma obstruction caused by pouch dilation and prolapse of stomach above the band. In extreme cases, this can cause strangulation and necrosis of the proximal stomach, so any LAGB patient in whom vomiting is not relieved by band deflation can be assumed to require an operation to remove or revise the band. Further contrast radiology may cause unnecessary delay and adversely affect the outcome, especially if the patient is unwell or in pain.

Investigating patients after gastroplasty

The majority of patients will present with reflux and dysphagia symptoms, and in most of these cases the underlying pathology will be the result of an ‘obstruction’ with proximal dilation and/or a hiatus hernia. In many cases, the hiatus hernia will be small, and any barium studies will be misreported. In Figure 27.2 only the first barium swallow (left panel) was interpreted correctly as reflux and a small hiatus hernia, the second (second panel from the left) of a VBG with reflux and hiatus hernia and the third (second panel from the right) with reflux and a slipped gastric band were not. Note the transverse lie of the band on the AP radiograph, which is a finding that is always associated with anterior pouch prolapse. The correct orientation of the band is seen on the fourth image (right panel), with the lie of the band pointing at 2 o’clock on the anteroposterior film.

Malabsorptive operations

Of the current malabsorptive operations, the Scopinaro and biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) procedures are the most effective long-term operations available with regards to maintenance of weight loss, and they have unparalleled results in diabetes and hyperlipidaemia resolution. They involve a limited gastrectomy and subtotal small intestine bypass which is achieved by anastomosing the ileum to the stomach (or pylorus), and bypassing the entire jejunum which is then anastomosed to the terminal ileum. Typically patients will have a short ‘enteric limb’ in which carbohydrate is absorbed and a ‘common channel’ of 25–100 cm of terminal ileum where biliary and pancreatic juices are mixed with the food to allow limited fat absorption.

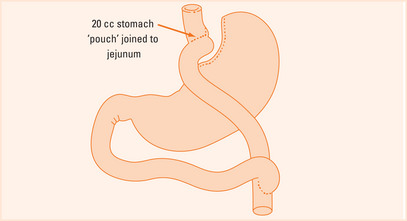

Gastric bypass

Gastric bypass is the most frequently performed bariatric procedure performed worldwide, and it may be performed via a laparoscopic or open approach. Gastric bypass is essentially just that, a bypass of the stomach, and gastroenterologists dealing with these patients can consider that they have had an operation analogous to a total gastrectomy (Figure 27.3).

Outside the early postoperative period where a therapeutic endoscopist may be asked to plug, glue or stent a leaking enteric anastomosis, potential complications revolve around the excluded stomach, the gastrojejunal anastomosis and bowel obstruction.

The most significant complication following gastric bypass surgery is the risk of small bowel obstruction and internal herniation of bowel through mesenteric defects with volvulus or ‘closed-loop’ obstruction. This can present insidiously as recurrent abdominal pain, sometimes mimicking biliary colic, pancreatitis, or appendicitis. Vomiting and obstipation may occur very late in the clinical course of the illness as a prelude to or a result of intestinal infarction. Plain abdominal radiology is unreliable or misleading, but high-resolution computed tomography (CT) with oral and intravenous contrast will usually diagnose those with evolving obstruction, often only recognised as an abnormality in mesenteric vasculature. For patients with intermittent or recurrent symptoms, laparoscopy is the only diagnostic test with sufficient predictive value to either prove or disprove recurrent obstruction, and elective repair of any defects is usually straightforward.

SUMMARY

Bariatric surgery complications are common. Potential complications can be grouped into:

Buchwald H, Buchwald J. Evolution of operative procedures for the management of morbid obesity 1950-2000. Obes Surg. 2002;12:705-717.

Buchwald H, Williams SE. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2003. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1157-1164.

Colquitt J, Clegg A, Sidhu M, et al. Surgery for morbid obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2003. CD003641

Dixon AF, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding induces prolonged satiety: a randomized blind crossover study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:813-819.

Greenway SE, Greenway FL, Klein S. Effects of obesity surgery on non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1109-1117.

Livingston E. Obesity and its surgical management. Am J Surg. 2002;184:103-113.

Vage V, Solhaug JH, Berstad A, et al. Jejunoileal bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a 25-year follow-up study of 36 patients. Obes Surg. 2002;12:312-318.