Chapter 39 OBESITY AND ABNORMAL LIVER FUNCTION TESTS

INTRODUCTION

Fatty liver or steatosis refers to the accumulation of fat within the liver. The fatty liver disorders are the most common cause of disturbances of liver function tests in the Western world. While there are several causes of fatty liver, including that of excessive consumption of alcohol (see Chapter 40), the commonest cause is that of insulin resistance usually (but not always) associated with one or a combination of obesity, hyperlipidaemia and/or hyperglycaemia. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the term used to describe steatosis unrelated to excessive alcohol consumption. NAFLD is a form of metabolic liver disease nearly always associated with insulin resistance and very often with the metabolic, or insulin resistance (IR), syndrome.

Risk factors

NAFLD is associated with central adiposity, obesity, hyperlipidaemia (particularly hypertriglyceridaemia, insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes—all conditions associated with insulin resistance (see Table 39.1). In addition, NAFLD is associated with rapid weight loss, particularly that observed after jejunoileal bypass surgery (Table 39.2).

TABLE 39.1 When to think about the insulin resistance syndrome

TABLE 39.2 Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its clinical associations

Natural history and prognosis

Obesity and fatty liver disorders have been associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, however the exact risk is not known. In a high proportion of patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis, the cirrhosis appears to be related to ‘burnt out’ NASH. That is, these patients fulfil the clinical profile of a patient with an underlying clinical profile of insulin resistance.

DIAGNOSIS

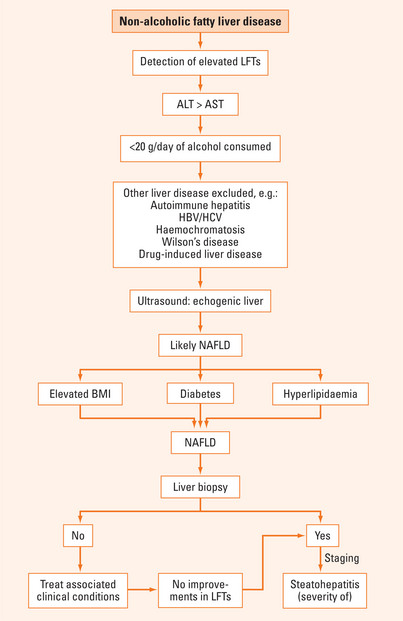

NAFLD is a clinicopathological diagnosis that requires the exclusion of other liver disorders. In particular, significant alcohol consumption (>20 g ethanol per day) must be excluded. Other common conditions that need to be excluded are chronic viral hepatitis (B and C), drug-induced liver disease, haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease and autoimmune liver disease. Certain drugs cause steatohepatitis (Table 39.3).

INVESTIGATIONS

Measurement of lipids

Hyperlipidaemia is frequently observed in patients with NAFLD. Elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels are commonly detected, usually with a disproportionate elevation of the triglyceride levels.

Who to biopsy?

Pathology

Steatosis or fatty infiltration is required to be present for a diagnosis of NAFLD. NASH, in addition, requires the presence of inflammation, liver cell injury and/or fibrosis. The extent of fibrosis is the most important prognostic variable when looking at severity and does not necessarily parallel liver enzyme levels.

MANAGEMENT

Lifestyle modifications

Minimising alcohol consumption (even abstaining) is very important. Alcohol consumption aggravates the formation of steatosis and induces pro-oxidant cofactors. This further enhances cellular injury. Interestingly, obesity and insulin resistance are now known to be important risk factors for fibrotic progression in alcoholic liver disease. The latter reflects the fact that many patients happen to have both heavy alcohol consumption and risk factors for NASH (obesity, insulin resistance, etc) and, consequently, the fatty liver disease has multiple aetiologies (both alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD).

Medications

SUMMARY

NAFLD is already the most common cause of abnormal liver function tests in the Western world. This acronym includes bland steatosis, steatosis with inflammation and/or fibrosis. Obesity, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia are frequently associated with NAFLD. Therefore, it is not surprising that most patients with NAFLD have underlying insulin resistance. Furthermore, the prevalence of NAFLD is increasing, paralleling the rise in the obesity epidemic observed in the Western world. Patients usually come to medical attention because of the detection of elevated liver enzymes, particularly elevated transaminases with an ALT >AST (Figure 39.1). Liver ultrasound frequently reveals a pattern of increased echogenicity. It is important to be aware that patients with NAFLD have an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Investigations include the need to measure lipid and blood glucose levels. Liver biopsy is frequently performed to confirm the diagnosis of NAFLD, to differentiate steatosis from NASH and to stage the disease. A proportion of patients with NAFLD develop progressive liver disease, ultimately leading to the development of cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation and (less commonly) hepatocellular carcinoma. The basis of management is that of slow and steady weight loss with appropriate dietary measures and exercise. Hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycaemia may require pharmacotherapy including the use of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, fibrates, biguanides and thiazolidinediones.

Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S99-S112.

Grant LM, Lisker-Melman M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:93-99.

McCullough AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:521-533. viii

Neuschwander-Tetri B. Fatty liver and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:193-198.