15 Obesity

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

BMI is calculated using a formula (weight (kg) ÷ [height (m)]2) or by using a BMI calculator, such as that provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/index.html.) BMI should be calculated and plotted on the appropriate standardized graph to ascertain the BMI percentile at every well-child visit.

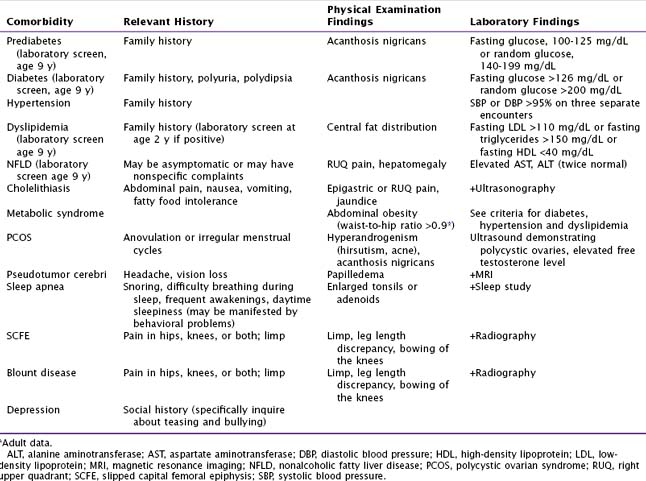

Laboratory evaluation such as fasting glucose, liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), and fasting lipids are used to screen patients for the common comorbidities associated with obesity. Additional tests should be ordered based on the history and physical examination (Table 15-1).

Management

Treatment Options

Behavioral

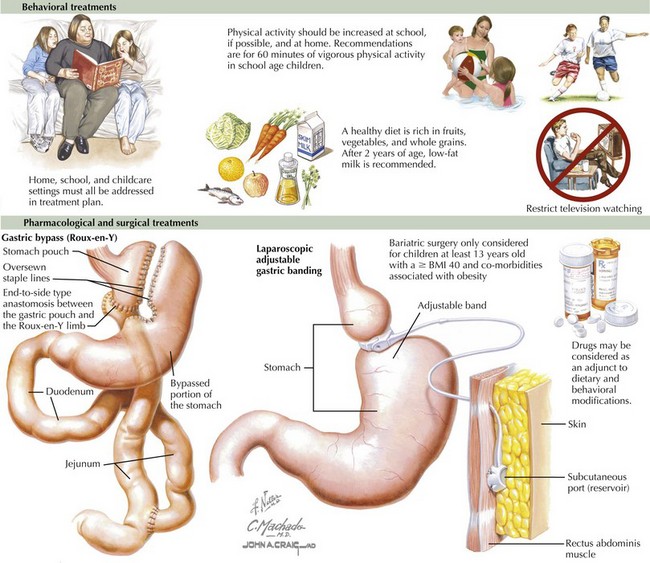

The management of obesity requires a multidisciplinary approach and should involve the patient’s family in all aspects of treatment planning. Research provides evidence that behavior modification is the most useful modality in the treatment of pediatric obesity. It is essential to use motivational interviewing and consider the readiness of the patient and his or her family in adopting the lifestyle changes necessary for management of obesity. Lifestyle interventions can focus on any or all areas of a child’s life: home, school, and childcare settings (Figure 15-1).

The American Heart Association has published recommendations for diet and exercise for children age 2 years and older. These include a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole-grain breads, and cereals with only a limited amount of juices, sugar-sweetened beverages, and processed foods. Children can easily consume excess calories in the form of beverages, and it is therefore important to follow current recommendations that include limiting juice intake to 4 to 6 oz/d, to include three servings of milk (whole milk until 2 years of age and then skim or 1% thereafter), and to frequently offer water (after age 6 months). Additionally, it is suggested that parents concentrate on limiting portion sizes and refer to nutritional labels when serving and preparing meals (see Figure 15-1).

For a number of reasons, over the past 30 to 40 years, schools have dramatically decreased their curriculum involving physical activity. Recent recommendations have included the addition of 60 minutes of vigorous physical activity in an average school day (see Figure 15-1).

Baranowski T, Berkowitz R, et al. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/meetings/workshops/child-obesity/

Barlow SE. the Expert Committee: Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(suppl):S164-S192.

2006 Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and the Brookings Institute: Childhood Obesity. The Future of Children. 16(1), 2006.