O

Obesity. Common and increasing problem in the Western world. Usually defined according to body mass index (see Table 12; p 79). Approximately 20% of UK adults are obese by this definition and this number has trebled in the last 20 years. Morbid obesity is defined as twice ideal body weight and affects 1% of the population; general mortality in this group is twice that of normal. Distribution of fat is thought to be more important than weight per se, with abdominal deposition particularly detrimental. Thus for a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, a waist (just above the navel) circumference of ≥ 94 cm indicates increased risk and ≥ 102 cm substantially increased risk for men; corresponding values for women are 80 cm and 88 cm respectively.

• Effects:

– reduced FRC because of the weight of the chest wall. FRC is especially reduced in the supine position, due to the weight of the abdominal wall and contents. Thoracic compliance is thus reduced, increasing work of breathing and O2 demand.  mismatch results in hypoxaemia.

mismatch results in hypoxaemia.

– hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction increases work of the right ventricle and may lead to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided cardiac failure.

– obstructive sleep apnoea and alveolar hypoventilation syndrome may occur.

– cardiac output and blood volume increase, to increase O2 flux.

– hypertension occurs in 60%; thus left ventricular work is increased. Left ventricular hypertrophy and ischaemia may occur, with resultant left-sided cardiac failure. Arrhythmias are common.

– ischaemic heart disease is common due to hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and physical inactivity.

other diseases are more likely, e.g. non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (caused by insulin resistance and inadequate insulin production, the latter worsening with age), hypercholesterolaemia, gout and arthritis, gallbladder disease, hepatic impairment due to fatty liver and cirrhosis, CVA, breast and endometrial malignancies.

other diseases are more likely, e.g. non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (caused by insulin resistance and inadequate insulin production, the latter worsening with age), hypercholesterolaemia, gout and arthritis, gallbladder disease, hepatic impairment due to fatty liver and cirrhosis, CVA, breast and endometrial malignancies.

Patients may present for bariatric surgery or other procedures. The former is usually done laparascopically and includes gastric banding, partial gastrectomy and gastric bypass, as single procedures or in combination.

– preoperative assessment for the above complications and appropriate management. Patients may be taking amfetamines or other drugs for weight loss.

– low-mw heparin prophylaxis is routine, because patients are less mobile and risk of DVT is increased. The ideal prophylactic dose is not certain in morbidly obese patients, but suggested regimens include enoxaparin 40 mg sc bd or 0.5 mg/kg od. Intermittent pneumatic calf compression should be used if possible.

– im injection may be difficult because of subcutaneous fat, while anti-DVT stockings may not fit.

– veins may be difficult to find and cannulate.

– hiatus hernia is common, with risk of aspiration of gastric contents. Volume and acidity of gastric contents may be increased. In addition, tracheal intubation may be difficult: insertion of the laryngoscope blade into the mouth may be hindered, the neck may be short and movement reduced.

– hypoxaemia may occur rapidly during apnoea, since FRC (hence O2 reserve) is reduced, and O2 consumption increased. FRC is increased if the patient is positioned head-up before induction of anaesthesia.

– airway maintenance is often difficult, because of increased soft tissue mass in the upper airway. Spontaneous ventilation is often inadequate because of respiratory impairment, which worsens in the supine position (especially in the head-down position or with legs in the lithotomy position). Thus IPPV is usually employed; high inflation pressures may be required.

– monitoring may be difficult, e.g. BP cuff too small, small ECG complexes.

– surgery is more likely to be difficult and prolonged, with increased blood loss.

– appropriate dosage may be difficult; e.g. neuromuscular blocking drugs are given according to lean body weight. Factors affecting drug pharmacokinetics include: changes in the volume of distribution due to decreased fraction of total body water, increased fatty tissue and increased lean body mass; increased drug clearance due to increased renal blood flow, increased GFR and tubular secretion; changes in plasma protein drug binding.

– increased metabolism of inhalational anaesthetic agents is thought to occur, e.g. increased fluoride ion concentrations after prolonged use of enflurane.

– atelectasis and hypoventilation are common, with increased risk of infection, hypoxaemia and respiratory failure. Patients are often best nursed sitting. Elective non-invasive positive pressure ventilation may be beneficial. Difficulty mobilising may be a problem.

– postoperative analgesia, O2 therapy and physiotherapy are especially important. CPAP therapy for obstructive sleep apnoea should be restarted in the immediate postoperative period. HDU or ICU admission is often required.

Similar considerations apply to admission of obese patients to ICU for non-surgical reasons.

Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (Pickwickian syndrome, after a character from Dickens’ Pickwick Papers). Obesity, daytime hypersomnolence, hypoxaemia and hypercapnia, often in the presence of right ventricular failure. Causes are multifactorial:

most patients have restrictive lung disease, resulting in poor compliance, increased work of breathing, alveolar hypoventilation and increased CO2 production. Pulmonary hypertension is present in 60% of patients.

most patients have restrictive lung disease, resulting in poor compliance, increased work of breathing, alveolar hypoventilation and increased CO2 production. Pulmonary hypertension is present in 60% of patients.

patients often have coexisting

patients often have coexisting  mismatch. Cyanosis and plethora are common, due to polycythaemia secondary to hypoxia.

mismatch. Cyanosis and plethora are common, due to polycythaemia secondary to hypoxia.

severe obstructive sleep apnoea is almost invariable. In addition there is a disordered central control of breathing, possibly due to leptin deficiency or resistance. Control is especially poor during sleep and sudden nocturnal death is common.

severe obstructive sleep apnoea is almost invariable. In addition there is a disordered central control of breathing, possibly due to leptin deficiency or resistance. Control is especially poor during sleep and sudden nocturnal death is common.

General and anaesthetic management is as for obesity and cor pulmonale. The FIO2 should be increased cautiously to avoid depression of the hypoxic ventilatory drive. CPAP may be useful to reduce hypercapnia and normalise O2 saturations. Respiratory depressant drugs should also be used cautiously; postoperative respiratory failure may occur.

[Charles Dickens (1812–1870), English author]

Piper AJ, Grunstein RR (2011). Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 183: 282–8

Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia. Strictly, ‘analgesia’ refers to removal of pain during labour and ‘anaesthesia’ is provided for operative delivery and other procedures. Pain during the first stage of labour is thought to be caused by cervical dilatation, and is usually felt in the T11–L1 dermatomes. Back and rectal pain may also occur. Pain often worsens at the end of the first stage. Pain during the second stage is caused by stretching of the birth canal and perineum.

Early attempts at pain relief included the use of abdominal pressure, opium and alcohol. Simpson administered the first obstetric anaesthetic in 1847, using diethyl ether. He used chloroform later that year, subsequently preferring it to ether. Moral and religious objections to anaesthesia in childbirth declined after Snow’s administration of chloroform to Queen Victoria in 1853. Regional techniques were introduced from the early 1900s, and have become increasingly popular since the 1960s.

Choice of technique is related to the physiological effects of pregnancy (especially risk of aortocaval compression and aspiration pneumonitis), and effects of drugs and complications on the fetus, neonate and course of labour. Anaesthesia has until the last 20–30 years been a major cause of maternal death, as revealed in the Reports on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths.

non-drug methods, e.g. TENS, acupuncture, hypnosis, psychoprophylaxis, audioanaesthesia (‘white noise’; high-frequency sound played through headphones), abdominal decompression (application of negative pressure to the abdomen): generally safe for mother and fetus, but of variable efficacy and thus rarely used, except for TENS and psychoprophylaxis.

non-drug methods, e.g. TENS, acupuncture, hypnosis, psychoprophylaxis, audioanaesthesia (‘white noise’; high-frequency sound played through headphones), abdominal decompression (application of negative pressure to the abdomen): generally safe for mother and fetus, but of variable efficacy and thus rarely used, except for TENS and psychoprophylaxis.

systemic opioid analgesic drugs:

systemic opioid analgesic drugs:

– morphine was used with hyoscine to provide twilight sleep in the early 1900s. However, it readily crosses the placenta to cause neonatal respiratory depression. pethidine was first used in 1940 and approved for use by UK midwives in 1950; it is the most commonly used opioid (e.g. 50–150 mg im up to two doses), but some units prefer diamorphine. 30–75% of women gain no benefit from pethidine and there is little evidence that opioids actually reduce pain scores. Nausea, vomiting, delayed gastric emptying and sedation may occur, with neonatal respiratory depression especially likely 2–4 h after im injection. Neonatal respiratory depression is marked after iv injection. Subtle changes may be detected on neurobehavioural testing of the neonate.

– other opioids have been used with similar effects. A lower incidence of neonatal depression has been claimed for partial agonists and agonist/antagonists (e.g. nalbuphine, pentazocine, meptazinol), but they are not commonly used.

– patient-controlled analgesia has been used, e.g. pethidine 10–20 mg iv or nalbuphine 2–3 mg iv (10 min lockout), or fentanyl 10–25 µg following 25–75 µg loading dose (3–5 min lockout). More recently, remifentanil has been used (e.g. 30–40 µg bolus, 2–3 min lockout), though severe respiratory depression has been reported.

– opioid receptor antagonists, e.g. naloxone, may be required if neonatal respiratory depression is marked.

sedative drugs: rarely used nowadays; promazine, promethazine, benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, clomethiazole and chlordiazepoxide have been used. All may cause neonatal depression.

sedative drugs: rarely used nowadays; promazine, promethazine, benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, clomethiazole and chlordiazepoxide have been used. All may cause neonatal depression.

inhalational anaesthetic agents:

inhalational anaesthetic agents:

– ether and chloroform were first used in 1847. Trichloroethylene was used in the 1940s, and methoxyflurane in 1970; formerly approved for midwives’ use with draw-over techniques, their use in the UK ceased in 1984.

– N2O was first used in 1880. Intermittent-flow anaesthetic machines were developed from the 1930s, using N2O with air or O2. Entonox was used in 1962 by Tunstall, and approved for use by midwives in 1965. It is usually self-administered using a face-piece or mouthpiece and demand valve. Slow deep inhalation should start just before a contraction begins, in order to achieve adequate blood levels at peak pain. May cause nausea and dizziness; it is otherwise relatively safe with minimal side effects, although maternal arterial desaturation has been reported, especially in combination with pethidine. Useful in 50% of women but of no help in 30% and, like opioids, there is little evidence that it reduces pain scores. Isoflurane has been added with good effect (Isoxane).

– enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and, more recently, sevoflurane have been used with draw-over inhalation.

general anaesthesia: no longer used for normal vaginal delivery. Problems are as for caesarean section.

general anaesthesia: no longer used for normal vaginal delivery. Problems are as for caesarean section.

regional techniques: involve blockade of the nerve supply of:

regional techniques: involve blockade of the nerve supply of:

– uterus:

– via sympathetic pathways in paracervical tissues and broad ligament to the spinal cord at T11–12, sometimes T10 and L1 also.

– the cervix is possibly innervated via separate S2–4 pathways in addition.

epidural anaesthesia/analgesia:

epidural anaesthesia/analgesia:

– caudal analgesia was first used in obstetrics in 1909 by Stoeckel; a continuous technique was introduced in the USA in 1942.

– reduces maternal exhaustion, hyperventilation, ketosis and plasma catecholamine levels.

– avoids adverse effects of parenteral opioids.

– reduces fetal acidosis and maintains or increases uteroplacental blood flow if hypotension is avoided.

– may improve contractions in incoordinate uterine activity.

– thought to reduce morbidity and mortality in breech delivery, multiple delivery, premature labour, pre-eclampsia, maternal cardiovascular or respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, forceps delivery and caesarean section.

– risk of hypotension, extensive blockade, iv injection and other complications. Post-dural puncture headache is more common than in non-pregnant subjects following accidental dural tap (the maximum acceptable incidence of the latter has been set at about 1% in the UK). Shivering and urinary retention may occur.

– requires 24-h dedicated anaesthetic cover.

– temporary reduction in uterine activity has been reported following injection of solution, though this may be caused by the bolus of crystalloid traditionally given concurrently.

– incoordinate uterine activity may improve.

– ventouse/forceps rate is increased; thought to occur because:

– patients likely to require forceps delivery are more likely to receive epidural analgesia.

– muscle tone is reduced, as above.

– standard techniques are used, but low doses of local anaesthetic agent are used to minimise motor block and risk of adverse effects. If higher doses are used, smaller volumes are required because venous engorgement reduces the volume of the epidural space. Hypotension is common with higher doses of local anaesthetic, especially in the presence of hypovolaemia; it is reduced by preloading with iv fluid, usually crystalloid (e.g. 0.9% saline/Hartmann’s solution, 500 ml). L2–3 or L3–4 interspaces are usually chosen, although, because identification of the lumber interspaces by palpation is not reliable (especially in pregnancy when the pelvis tilts), anaesthetists often place the catheter at a higher interspace than that intended.

– bupivacaine is traditionally preferred, since fetal transfer is least. Others have been used, e.g. lidocaine, chloroprocaine. prilocaine is rarely used because of the risk of methaemoglobinaemia. Ropivacaine is claimed to cause less motor block than bupivacaine when higher concentrations are used. Levobupivacaine has a better safety profile, but with low-dose regimens this difference becomes less relevant.

– use of a test dose is controversial. With low-dose regimens, the first dose is also the test dose.

– epidural opioids have been used alone, but rarely in the UK (see Spinal opioids). Fentanyl is usually added to weak solutions of bupivacaine as above. In the USA, sufentanil is often used. Epidural pethidine has also been used.

– contraindications, complications and management are as for epidural analgesia/anaesthesia. Care should be taken in antepartum haemorrhage (see below). Extensive blockade and accidental iv injection of local anaesthetic are possible following catheter migration. All blocks should be regularly assessed and an anaesthetist should be readily available, with resuscitative drugs and equipment. Maximal doses of local anaesthetic agents should not be exceeded in a 4-h period.

Backache and neurological damage may be caused by labour itself, although epidural analgesia is often blamed by the patient and non-anaesthetic staff.

spinal anaesthesia was first used in 1900. Popular in the USA in the 1920s, it only increased in popularity in the UK towards the end of the 1900s. Technique and management are as standard, but with more rapid onset of hypotension and greater incidence of post-dural puncture headache and variable blocks (especially using plain bupivacaine) than in non-pregnant subjects. Dose requirements are reduced, possibly due to altered CSF dynamics, although changes in CSF pH, proteins and volume have been suggested. Effects are as for epidural anaesthesia. Mostly used for caesarean section, forceps and ventouse delivery and removal of retained placenta. Doses for vaginal procedures: 1.0–1.6 ml heavy bupivacaine 0.5%; lower doses with opioids have also been used.

spinal anaesthesia was first used in 1900. Popular in the USA in the 1920s, it only increased in popularity in the UK towards the end of the 1900s. Technique and management are as standard, but with more rapid onset of hypotension and greater incidence of post-dural puncture headache and variable blocks (especially using plain bupivacaine) than in non-pregnant subjects. Dose requirements are reduced, possibly due to altered CSF dynamics, although changes in CSF pH, proteins and volume have been suggested. Effects are as for epidural anaesthesia. Mostly used for caesarean section, forceps and ventouse delivery and removal of retained placenta. Doses for vaginal procedures: 1.0–1.6 ml heavy bupivacaine 0.5%; lower doses with opioids have also been used.

CSE has been advocated because of its rapid onset and intense quality of analgesia (from the spinal component), with subsequent management as for epidural analgesia. Its routine place in labour is controversial because of its increased cost, the increased risk of post-dural puncture headache, damage to the conus medullaris and (theoretical) concerns over increased risk of infection. In addition, the unreliability of identifying the lumbar interspaces by palpation may result in insertion of the needle at a higher vertebral level than intended. The lowest easily palpable interspace should therefore be chosen, and an epidural-only technique used above L3–4.

CSE has been advocated because of its rapid onset and intense quality of analgesia (from the spinal component), with subsequent management as for epidural analgesia. Its routine place in labour is controversial because of its increased cost, the increased risk of post-dural puncture headache, damage to the conus medullaris and (theoretical) concerns over increased risk of infection. In addition, the unreliability of identifying the lumbar interspaces by palpation may result in insertion of the needle at a higher vertebral level than intended. The lowest easily palpable interspace should therefore be chosen, and an epidural-only technique used above L3–4.

paravertebral block: bilateral blocks are required at either L2 (for sympathetic block) or T11–12 (somatic block).

paravertebral block: bilateral blocks are required at either L2 (for sympathetic block) or T11–12 (somatic block).

paracervical block: rarely performed because of fetal arrhythmias.

paracervical block: rarely performed because of fetal arrhythmias.

pudendal nerve block and perineal infiltration/spraying with local anaesthetic: only of use for the second stage. Pudendal block is used for forceps and ventouse delivery.

pudendal nerve block and perineal infiltration/spraying with local anaesthetic: only of use for the second stage. Pudendal block is used for forceps and ventouse delivery.

local infiltration of the abdomen for caesarean section.

local infiltration of the abdomen for caesarean section.

• Particular problems in obstetric anaesthetic practice:

obstetric conditions, e.g. pre-eclampsia, placenta praevia, placental abruption, postpartum haemorrhage. Haemorrhage may follow any delivery, and facilities for urgent transfusion should be available, including a cut-down set and O-negative uncross-matched blood. DIC may also occur in septic abortion, intrauterine death, hydatidiform mole and severe shock.

obstetric conditions, e.g. pre-eclampsia, placenta praevia, placental abruption, postpartum haemorrhage. Haemorrhage may follow any delivery, and facilities for urgent transfusion should be available, including a cut-down set and O-negative uncross-matched blood. DIC may also occur in septic abortion, intrauterine death, hydatidiform mole and severe shock.

fluid overload associated with oxytocin administration; pulmonary oedema associated with tocolytic drugs.

fluid overload associated with oxytocin administration; pulmonary oedema associated with tocolytic drugs.

specific procedures/presentations:

specific procedures/presentations:

– causes include: shock associated with abruption and DIC, postpartum haemorrhage, total spinal blockade, overdosage or iv injection of local anaesthetic, amniotic fluid embolism, PE, eclampsia, inversion of the uterus and pre-existing disease.

– CPR is hindered by aortocaval compression, relieved by tilting the patient to one side or manually displacing the uterus laterally. Caesarean section should be undertaken within 5 min if there is no improvement in the mother’s condition.

See also, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, neonatal; Ergometrine; Fetal monitoring; Flying squad, obstetric; Labour, active management of; Midwives, prescription of drugs by; Obstetric intensive care

Obstetric intensive care. Required in 0.2–9 cases per 1000 deliveries, depending on the population served and the ICU admission criteria used. Most common reasons for admission are haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome; a mortality of 3–4% is reported in UK series but up to 20% has been reported elsewhere. Main problems are related to the risks to the fetus and the physiological changes of pregnancy: obstetric patients have increased oxygen demands and reduced respiratory reserves, and are more susceptible to aspiration of gastric contents, aortocaval compression, acute lung injury, DVT and DIC.

General management is along standard lines, with attention to the above complications. Excessive fluid administration should be avoided, since ARDS is a common feature of obstetric critical illness. Fetal monitoring should be ensured if antepartum, although the needs of the mother outweigh those of the fetus. Uteroplacental blood flow may be impaired by vasopressors and the mother may be too sick to receive tocolytic drugs should premature labour occur. Caesarean section may be required to improve the mother’s condition. Breast milk may be unsuitable for use because of maternal drugs; if required, lactation can be suppressed with bromocriptine (although hypertension, CVA and MI have followed its use, hence it should be avoided in hypertensive disorders).

Price LC, Slack A, Nelson-Piercy C (2008). Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol; 5: 775–99

See also, Placenta praevia; Placental abruption; Postpartum haemorrhage

Obstructive sleep apnoea, see Sleep apnoea/hypopnoea

Obturator nerve block. Performed to accompany sciatic nerve block or femoral nerve block, or in the diagnosis and treatment of hip pain. The obturator nerve (L2–4), a branch of the lumbar plexus, passes down within the pelvis and through the obturator canal into the thigh, to supply the hip joint, anterior adductor muscles and skin of medial lower thigh/knee.

With the patient supine and the leg slightly abducted, an 8 cm needle is inserted 1–2 cm caudal and lateral to the pubic tubercle, and directed slightly medially to encounter the pubic ramus. It is then withdrawn and redirected laterally to enter the obturator canal, and advanced 2–3 cm. If a nerve stimulator is used, twitches in the adductor muscles are sought. After careful aspiration to exclude intravascular placement, 10–15 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected.

Occipital nerve blocks, see Scalp, nerve blocks

Octreotide. Long-acting somatostatin analogue, used in carcinoid syndrome and related GIT tumours and acromegaly. Also licensed for use in treating complications of pancreatic surgery. Has also been used in bleeding oesophageal varices, and to reduce vomiting in palliative care. Plasma levels peak within an hour of sc administration, and within a few minutes of iv injection. Half-life is 1–2 h. Lanreotide is a similar agent.

Oculocardiac reflex. Bradycardia following traction on the extraocular muscles, especially medial rectus. Afferent pathways are via the occipital branch of the trigeminal nerve; efferents are via the vagus. The reflex is particularly active in children. Bradycardia may be severe, and may lead to asystole. Other arrhythmias may occur, e.g. ventricular ectopics or junctional rhythm. Bradycardia may also follow pressure on or around the eye, fixation of facial fractures, etc. The reflex has been used to stop SVT with eyeball massage. Reduced by anticholinergic drugs administered as premedication or on induction of anaesthesia. If it occurs, surgery should stop, and atropine or glycopyrronium should be administered. Retrobulbar block does not reliably prevent it; local infiltration of the muscles has been used instead.

Oculogyric crises, see Dystonic reactions

Oculorespiratory reflex. Hypoventilation following traction on the external ocular muscles. Reduced respiratory rate, reduced tidal volume or irregular ventilation may occur. Thought to involve the same afferent pathways as the oculocardiac reflex, but with efferents via the respiratory centres. Heart rate may be unchanged, and the reflex is unaffected by atropine.

ODAs/ODPs, see Operating department assistants/practitioners

Odds ratio. Ratio of the odds of an event’s occurrence in one group to its odds in another, used as an indicator of treatment effect in clinical trials. For example, if a disease is suspected to be caused by exposure to a certain factor, a 2 × 2 table may be drawn for proportions of patients in the following groups:

| With disease | Without disease | |

| Exposed | a | c |

| Not exposed | b | d |

| Odds ratio | = the ratio of a/b to c/d |

| = ad/bc. |

Harder to understand (but more useful mathematically) than other indices of risk commonly used.

See also, Absolute risk reduction; Meta-analysis; Number needed to treat; Relative risk reduction

O’Dwyer, Joseph (1841–1898). US physician; regarded as the introducer of the first practical intubation tube in 1885, although the technique had been described previously by others, e.g. Kite. His short metal tube, used as an alternative to tracheostomy in diphtheria, was inserted blindly into the larynx on an introducer; the flanged upper end rested on the vocal cords. He mounted his tube on a handle for use with Fell’s resuscitation bellows in 1888; the Fell–O’Dwyer apparatus could be used for CPR or anaesthesia. Later modifications included addition of a cuff.

Oedema. Generalised or local excess ECF. Caused by:

hypoproteinaemia and decreased plasma oncotic pressure.

hypoproteinaemia and decreased plasma oncotic pressure.

increased hydrostatic pressure, e.g. cardiac failure, venous or lymphatic obstruction; salt and water retention (e.g. renal impairment, drugs, e.g. NSAIDs, oestrogens, corticosteroids).

increased hydrostatic pressure, e.g. cardiac failure, venous or lymphatic obstruction; salt and water retention (e.g. renal impairment, drugs, e.g. NSAIDs, oestrogens, corticosteroids).

leaky capillary endothelium, e.g. inflammation, allergic reactions, toxins.

leaky capillary endothelium, e.g. inflammation, allergic reactions, toxins.

direct instillation, e.g. extravasated iv fluids, infiltration. Several causes often coexist, e.g. hypoproteinaemia, portal hypertension and fluid retention in hepatic failure. Characterised by pitting when prolonged digital pressure is applied, although fibrosis reduces this in chronic oedema. Generalised oedema occurs in dependent parts of the body, e.g. ankles if ambulant, sacrum if bed-bound. Treatment is directed at the cause. If localised, the affected part is raised above the heart.

direct instillation, e.g. extravasated iv fluids, infiltration. Several causes often coexist, e.g. hypoproteinaemia, portal hypertension and fluid retention in hepatic failure. Characterised by pitting when prolonged digital pressure is applied, although fibrosis reduces this in chronic oedema. Generalised oedema occurs in dependent parts of the body, e.g. ankles if ambulant, sacrum if bed-bound. Treatment is directed at the cause. If localised, the affected part is raised above the heart.

See also, Cerebral oedema; Hereditary angioedema; Pulmonary oedema; Starling’s forces

Oesophageal contractility. Used as an indicator of anaesthetic depth and brainstem integrity. Skeletal muscle is present in the upper third of the oesophagus, smooth muscle in the lower third, and both types in the middle third. Afferent and efferent nerve supply is mainly vagal via oesophageal plexuses, but also via sympathetic nerves.

• Normal pattern of contractions:

primary: continuation of the swallowing process; propels the food bolus down the oesophagus.

primary: continuation of the swallowing process; propels the food bolus down the oesophagus.

tertiary (spontaneous): non-peristaltic; function is uncertain.

tertiary (spontaneous): non-peristaltic; function is uncertain.

Measured by passing a double-ballooned probe into the lower oesophagus. The distal balloon is filled with water and connected to a pressure transducer; the other balloon (just proximal) may be inflated intermittently to study provoked contractions.

anaesthesia: provoked contractions diminish in amplitude as depth increases, and spontaneous contractions become less frequent. Oesophageal contractility index ([70 × spontaneous rate] + provoked amplitude) is used as an overall measure of activity. Thought to be analogous to BP, heart rate, lacrimation and sweating during anaesthesia; i.e. suggestive of anaesthetic depth, but not reliable. Activity may be decreased by atropine and smooth muscle relaxants (e.g. sodium nitroprusside) and increased by neostigmine.

anaesthesia: provoked contractions diminish in amplitude as depth increases, and spontaneous contractions become less frequent. Oesophageal contractility index ([70 × spontaneous rate] + provoked amplitude) is used as an overall measure of activity. Thought to be analogous to BP, heart rate, lacrimation and sweating during anaesthesia; i.e. suggestive of anaesthetic depth, but not reliable. Activity may be decreased by atropine and smooth muscle relaxants (e.g. sodium nitroprusside) and increased by neostigmine.

brainstem death: spontaneous contractions disappear, and provoked contractions show a low amplitude pattern. Has been used to indicate the presence or absence of brainstem activity in ICU, but its role is controversial. Presently not included in UK brainstem death criteria.

brainstem death: spontaneous contractions disappear, and provoked contractions show a low amplitude pattern. Has been used to indicate the presence or absence of brainstem activity in ICU, but its role is controversial. Presently not included in UK brainstem death criteria.

Oesophageal obturators and airways. Devices inserted blindly into the oesophagus of unconscious patients to secure the airway and allow IPPV when tracheal intubation is not possible, e.g. by untrained personnel. They have been used in failed intubation. Consist of a cuffed oesophageal tube, often attached to a facemask for sealing the mouth and nose and preventing air leaks. The cuff reduces gastric insufflation and regurgitation but may not prevent it.

The epiglottis is pushed anteriorly, creating an air passage for ventilation. An ordinary tracheal tube may be used to isolate the stomach and improve the airway in a similar way.

• Two main types are described:

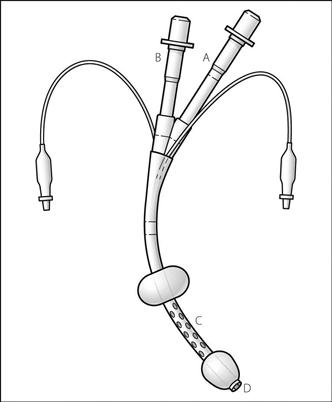

The above features have been combined in a double-lumen device (Combitube), which may be placed in either the oesophagus or trachea (Fig. 121). A distal cuff (15 ml) seals the oesophagus or trachea, whilst a proximal balloon (100 ml) seals the oral and nasal airways. IPPV may be performed through either tube depending on the device’s position; it enters the oesophagus in over 95% of cases initially and ventilation via the longer proximal tube (A) will result in pulmonary ventilation via the proximal openings (C). The shorter distal tube (B) may then be used for gastric suction via the distal opening (D). If the device is tracheal, IPPV may be achieved via tube B and opening D. Has been suggested as a suitable device for non-medical personnel (e.g. for CPR), although trauma is more common than with alternative devices, such as the LMA.

Fig. 121 The Combitube (see text)

Oesophageal sphincter, see Lower oesophageal sphincter

Oesophageal stethoscope, see Stethoscope

Oesophageal varices. Dilated oesophagogastric veins occurring in portal hypertension, e.g. in hepatic cirrhosis; the veins represent one of the connections between the systemic and portal circulations. Account for up to a third of cases of massive upper GIT haemorrhage. Mortality is up to 30% if bleeding occurs, partly related to the underlying severity of liver disease.

prevention of haemorrhage: β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, e.g. propranolol, have been used to reduce portal BP if hepatic function is not too impaired. Endoscopic sclerotherapy (e.g. with ethanolamine oleate or sodium tetradecyl sulphate; causes variceal thrombosis and fibrosis) and ligation (e.g. with rubber bands) are also used. Portocaval shunt procedures, e.g. distal splenorenal shunts (requiring surgery) or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS; performed under radiological control) decompress the portal circulation but at the expense of hepatic encephalopathy (possibly less common after TIPS). The effect of all these procedures on survival is disputed.

prevention of haemorrhage: β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, e.g. propranolol, have been used to reduce portal BP if hepatic function is not too impaired. Endoscopic sclerotherapy (e.g. with ethanolamine oleate or sodium tetradecyl sulphate; causes variceal thrombosis and fibrosis) and ligation (e.g. with rubber bands) are also used. Portocaval shunt procedures, e.g. distal splenorenal shunts (requiring surgery) or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS; performed under radiological control) decompress the portal circulation but at the expense of hepatic encephalopathy (possibly less common after TIPS). The effect of all these procedures on survival is disputed.

– resuscitation as for acute hypovolaemia. Airway management is complicated by haematemesis and steps to avoid aspiration of blood and gastric contents must be taken.

– pharmacological reduction of portal venous pressure:

– vasopressin 20 U over 15 min iv or its analogue terlipressin 2 mg iv followed by 1–2 mg 4–6-hourly up to 72 h. Controls bleeding in 60–70% of cases.

– somatostatin 250 µg followed by 250 µg/h or its analogue octreotide 50 µg followed by 50 µg/h.

– endoscopic sclerotherapy or ligation may be performed acutely.

– radiological procedures include embolisation or TIPS.

‘Off-pump’ coronary artery bypass graft, see Coronary artery bypass graft

Ofloxacin. Antibacterial drug, one of the 4-quinolones related to ciprofloxacin. Used for respiratory and genitourinary tract infections.

Ohm’s law. Current passing through a conductor is proportional to the potential difference across it, at constant temperature. Thus: voltage = current × resistance. (i.e. V = IR). An analogous form exists for flow of a fluid: pressure = flow × resistance.

Old age, see Elderly, anaesthesia for

Oliguria. Reduced urine output; definition is controversial but usually described as under 0.5 ml/kg/h. Common after major surgery or in ICU.

urinary retention, blocked catheter, etc.

urinary retention, blocked catheter, etc.

poor renal perfusion, e.g. hypotension, hypovolaemia, low cardiac output. Urine formation usually requires MAP of 60–70 mmHg in normotensive subjects.

poor renal perfusion, e.g. hypotension, hypovolaemia, low cardiac output. Urine formation usually requires MAP of 60–70 mmHg in normotensive subjects.

effect of drugs, e.g. morphine causes vasopressin secretion.

effect of drugs, e.g. morphine causes vasopressin secretion.

exclusion of retention or blocked catheter.

exclusion of retention or blocked catheter.

urinary and plasma chemical analysis (e.g. sodium, osmolality) is useful in distinguishing renal from prerenal causes (see Renal failure). Management is according to the underlying cause.

urinary and plasma chemical analysis (e.g. sodium, osmolality) is useful in distinguishing renal from prerenal causes (see Renal failure). Management is according to the underlying cause.

Omeprazole. Proton pump inhibitor used to reduce gastric acidity. A prodrug converted to its active form by the acidic conditions of gastric parietal cell canaliculi. Effects last for up to 24 h after single dosage.

Omphalocele, see Gastroschisis and exomphalos

Oncotic pressure (Colloid osmotic pressure). Osmotic pressure exerted by plasma proteins, usually about 3.3 kPa (25 mmHg). Important in the balance of Starling forces, and movement of water across capillary walls, e.g. in oedema. Although related to plasma protein concentration, the relationship is thought to be non-linear because of molecular interactions and effects of charge.

Ondansetron hydrochloride. 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, introduced in 1990 as an antiemetic drug following anaesthesia and chemotherapy. Although claimed to be superior to alternative antiemetics for PONV, convincing evidence for this is lacking. However, it does not affect dopamine receptors and unwanted central effects are rare. Evidence suggests greater efficacy for treatment of PONV, than for its prophylaxis. Has also been used to treat intractable pruritus following spinal opioids, although evidence for its effectiveness is weak. Decreases the incidence of postoperative shivering. Only 70–75% protein-bound. Undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion. Half-life is 3 h.

• Dosage:

– treatment: 1–4 mg slowly iv/im.

• Side effects: headache, constipation, flushing sensation, hiccups, occasionally hepatic impairment, visual disturbances, rarely convulsions. Prolongation of ECG intervals, including heart block, has been reported. May reduce the analgesic efficacy of tramadol hydrochloride.

Ondine’s curse. Hypoventilation caused by reduced ventilatory drive, originally described following CNS surgery (classically to medulla/high cervical spine). Despite being awake, victims may breathe only on command, with apnoea when asleep. The term has also been applied to a congenital form of hypoventilation and to respiratory depression caused by opioid analgesic drugs.

Nannapaneni R, Behari S, Todd NV, Mendelow AD (2006). Neurosurg; 57: 354–63

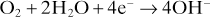

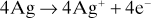

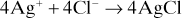

One-lung anaesthesia. Deliberate perioperative collapse of one lung to allow or facilitate thoracic surgery, whilst maintaining ventilation and gas exchange on the other side. Requires the use of endobronchial tubes or blockers. Commonly performed for surgery to the lungs, oesophagus, aorta and mediastinum, but most operations are possible without it (sleeve resection of the bronchus being a notable exception). Its main problem is related to hypoxaemia caused by the  mismatch produced, exacerbated by the lateral position used for most thoracic surgery. Perioperative hypoxaemia increases postoperative risk of cognitive dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, renal failure and pulmonary hypertension.

mismatch produced, exacerbated by the lateral position used for most thoracic surgery. Perioperative hypoxaemia increases postoperative risk of cognitive dysfunction, atrial fibrillation, renal failure and pulmonary hypertension.

• Effects of lateral positioning on gas exchange:

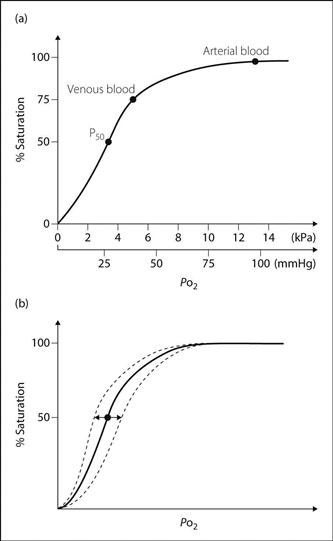

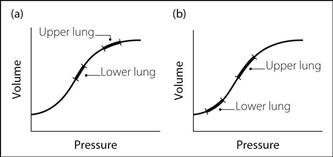

– ventilation: FRC of the upper lung exceeds that of the lower lung, because of mediastinal movement to the dependent side, and pushing up of the lower hemidiaphragm by abdominal viscera. Thus the upper lung lies on a flatter part of the compliance curve (i.e. is less compliant) whilst the lower lung lies on the steep part of curve, i.e. is more compliant (Fig. 122a). In addition, the raised hemidiaphragm on the dependent side contracts more effectively. Thus most ventilation is of the lower lung.

Fig. 122 Compliance curve for upper and lower lungs in the lateral position: (a) awake; (b) anaesthetised

– perfusion: mainly of the lower lung because of gravity; i.e. is matched with ventilation.

– FRC of both lungs is reduced; the upper lung now lies on the steep part of the curve and the lower lung on the flatter part (Fig. 122b). Thus the upper (more compliant) lung is ventilated in preference to the lower (less compliant) lung.

one-lung anaesthesia: all ventilation is of the lower lung, whereas considerable perfusion is still of the upper lung. Thus significant shunt occurs in the upper lung, with

one-lung anaesthesia: all ventilation is of the lower lung, whereas considerable perfusion is still of the upper lung. Thus significant shunt occurs in the upper lung, with  mismatch usual in the lower lung.

mismatch usual in the lower lung.

– degree of hypoxaemia is affected by:

– hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: whether it is attenuated by use of anaesthetic agents, or whether it contributes any protection against shunt, is unclear.

– ventilation strategy: the optimum tidal volume and level of PEEP are controversial. In order to prevent atelectasis in the dependent lung, some advocate using large tidal volumes (e.g. 12 ml/kg) without PEEP (as PEEP may reduce cardiac output or increase shunt through the uppermost lung, exacerbating hypoxaemia). An increasingly common strategy is to use low tidal volumes (e.g. 6–7 ml/kg) with moderate PEEP to prevent atelectasis while reducing the risk of causing volutrauma and acute lung injury.

preoperative assessment as for thoracic surgery; patients particularly at risk during one-lung anaesthesia may be identified.

preoperative assessment as for thoracic surgery; patients particularly at risk during one-lung anaesthesia may be identified.

close monitoring using oximetry and/or arterial blood gas interpretation.

close monitoring using oximetry and/or arterial blood gas interpretation.

FIO2 is usually set to 0.4–0.5.

FIO2 is usually set to 0.4–0.5.

surgical ligation of the pulmonary artery is performed early.

surgical ligation of the pulmonary artery is performed early.

management of acute desaturation includes:

management of acute desaturation includes:

– use of fibreoptic bronchoscopy to check tube position and clear secretions.

– administration of O2 to the uppermost lung, e.g. with CPAP or intermittent inflation.

– performing an alveolar recruitment manoeuvre on the dependent lung.

– altering the ventilation strategy (i.e. changing tidal volume and/or PEEP).

suction is applied to the collapsed lung before reinflation, to remove accumulated secretions.

suction is applied to the collapsed lung before reinflation, to remove accumulated secretions.

Karzai W, Schwarzkopf K (2009). Anesthesiology; 110: 1402–11

Open-drop techniques. Common and convenient techniques for administering inhalational anaesthetic agents in the 1800s/early 1900s. The volatile anaesthetic agent (e.g. chloroform, diethyl ether, ethyl chloride) was dripped on to a cloth (originally a folded handkerchief) on the patient’s face from a dropper bottle. Concentration of agent depended on the rate of drop administration. Specially designed bottles and masks were later developed; the best-known mask is that of Schimmelbusch, although this was adapted from Skinner’s earlier model. Some incorporated channels for O2 insufflation, or gutters around the edge to catch liquid anaesthetic.

[Curt Schimmelbusch (1860–1895), German surgeon; Thomas Skinner (1825–1906), Liverpool obstetrician]

Operant conditioning. Type of learning in which voluntary behaviour is strengthened or weakened by rewards or punishments respectively. May be involved in the development of certain behavioural aspects of pain syndromes. Has been used in chronic pain management, with several weeks’ admission to hospital, involving reduction in drug therapy and encouragement of activity and independence. Thus concentrates on behaviour secondary to pain instead of pain itself.

Ophthalmic nerve blocks. Performed for procedures around the eye, nose and forehead, and certain intraoral procedures.

• Anatomy (see Fig. 76; Gasserian ganglion block):

ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) is entirely sensory and passes from the Gasserian ganglion, where it divides into branches which pass through the superior orbital fissure:

ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) is entirely sensory and passes from the Gasserian ganglion, where it divides into branches which pass through the superior orbital fissure:

• Blocks:

supraorbital nerve: 1–3 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected at the supraorbital notch.

supraorbital nerve: 1–3 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected at the supraorbital notch.

supratrochlear nerve: 1–3 ml is injected at the superomedial part of the opening of the orbit.

supratrochlear nerve: 1–3 ml is injected at the superomedial part of the opening of the orbit.

both the above nerves may be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration above the eyebrow.

both the above nerves may be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration above the eyebrow.

frontal nerve: 1 ml is injected at the central part of the roof of the orbit.

frontal nerve: 1 ml is injected at the central part of the roof of the orbit.

Ophthalmic surgery. Historically, first performed without anaesthesia and then under topical anaesthesia (e.g. by Koller), because of the eye’s accessibility and the disastrous effects of coughing during general anaesthesia. Subsequently, increasingly performed under general anaesthesia because of patients’ expectations and the ability to control intraocular pressure (IOP). More recently local anaesthesia has been favoured again, especially in the elderly. Children (for strabismus repair) and the elderly (for cataract extraction) form the largest groups of patients.

cornea and conjunctiva: 4% lidocaine (with or without adrenaline) or 2–4% cocaine is instilled into the conjunctival sac. Cocaine is not used in glaucoma, as it dilates the pupil.

cornea and conjunctiva: 4% lidocaine (with or without adrenaline) or 2–4% cocaine is instilled into the conjunctival sac. Cocaine is not used in glaucoma, as it dilates the pupil.

retrobulbar block, peribulbar block or sub-Tenon’s block: retrobulbar block is less commonly performed now because of associated complications.

retrobulbar block, peribulbar block or sub-Tenon’s block: retrobulbar block is less commonly performed now because of associated complications.

sedation may be used. Close monitoring is required as the patient’s head is covered by drapes. Supplementary O2 should be delivered.

sedation may be used. Close monitoring is required as the patient’s head is covered by drapes. Supplementary O2 should be delivered.

– preoperative assessment of children with strabismus for muscle disorders and MH susceptibility. Cataracts may occur in dystrophia myotonica, inborn errors of metabolism, chromosomal abnormalities, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroids therapy or following trauma. Lens subluxation may occur in Marfan’s syndrome and inborn errors, e.g. homocystinuria. The elderly should be assessed for other diseases, e.g. diabetes, hypertension (see Elderly, anaesthesia for).

– drugs used in eye drops may be absorbed and active systemically, e.g. ecothiopate, timolol.

– opioid premedication is usually avoided because of its emetic properties. Benzodiazepines are popular.

– procedures include the above operations, repair of retinal detachment, vitrectomy, repair of eye injuries (see Eye, penetrating injury) and operations on the lacrimal system.

– the airway is usually not easily accessible to the anaesthetist.

– for children, considerations include those for paediatric anaesthesia, the very active oculocardiac and oculorespiratory reflexes, and the increased incidence of PONV after strabismus repair (thought also to be associated with traction on extraocular muscles). Atropine or glycopyrronium should be available; some advocate routine administration to all patients preoperatively or on induction of anaesthesia. Standard techniques are employed, with tracheal intubation or LMA and spontaneous or controlled ventilation.

– for adults, standard agents and techniques are used. Control of IOP is usually achieved by iv induction, IPPV and hyperventilation, and use of a volatile inhalational anaesthetic agent (for effects of specific drugs, use of sulphahexafluoride, etc., see Intraocular pressure). Administration of iv acetazolamide may be required. Spontaneous ventilation may be suitable for extraocular procedures. The LMA is often used, since coughing and straining are less pronounced than with tracheal intubation. The oculocardiac reflex may still occur in adults.

– systemic absorption of topical solutions, e.g. adrenaline, cocaine, may occur.

– coughing, straining and vomiting may increase IOP, especially undesirable if the globe is open.

Opiates. Strictly, substances derived from opium. Formerly used to describe agonist drugs at opioid receptors; the terms opioids and opioid analgesic drugs are now preferred.

Opioid analgesic drugs. Opium and morphine have been used for thousands of years; morphine was isolated in 1803 and codeine in 1832. Diamorphine was introduced in 1898, papaveretum in 1909. Other commonly used drugs include: pethidine (1939); methadone (1947); phenoperidine (1957); fentanyl (1960); alfentanil (1976); tramadol (1977); sufentanil (1984) and remifentanil (1997). Drugs with opioid receptor antagonist properties include pentazocine (1962), nalbuphine (1968), meptazinol (1971) and buprenorphine (1968).

May be divided into naturally occurring alkaloids (e.g. morphine, codeine), semisynthetic drugs (slightly modified natural molecules, e.g. diamorphine, dihydrocodeine) and synthetic opioids (e.g. pethidine, fentanyl, alfentanil, remifentanil). May also be classified according to their opioid receptor specificity and actions, or according to their onset and duration of action.

Each drug has slightly different effects on the body’s systems, but their general effects are those of morphine. The ‘purer’ drugs, e.g. fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, do not cause histamine release, and may be used in very high doses with relative cardiostability, e.g. for cardiac surgery. In lower doses, they are used to provide intra- and postoperative analgesia, and to prevent the haemodynamic consequences of tracheal intubation and surgical stimulation. Also used as general analgesic drugs and for premedication, anxiolysis, cough suppression and treatment of chronic diarrhoea.

Opioid detoxification, see Rapid opioid detoxification

Opioid poisoning. Presents with nausea and vomiting, respiratory depression, hypotension, pinpoint pupils and coma. Depressant effects are exacerbated by alcohol ingestion. Hypothermia, hypoglycaemia and, rarely, pulmonary oedema and rhabdomyolysis may occur. Convulsions may occur with pethidine, codeine and dextropropoxyphene. Drug combinations containing opioids include atropine–diphenoxylate for diarrhoea and paracetamol–dextropropoxyphene/codeine/dihydrocodeine for pain. The former combination may cause convulsions, tachycardia and restlessness (hence it has been withdrawn from US and UK markets); the latter may cause delayed hepatic failure.

supportive: includes gastric lavage, iv fluids, O2 therapy and IPPV. Activated charcoal may be helpful if oral opioids have been recently ingested.

supportive: includes gastric lavage, iv fluids, O2 therapy and IPPV. Activated charcoal may be helpful if oral opioids have been recently ingested.

naloxone 0.4–2.0 mg iv repeated after 2–3 min as required to a total of 10 mg; infusion may be necessary as its duration of action is short. Respiratory depression due to buprenorphine may not be responsive.

naloxone 0.4–2.0 mg iv repeated after 2–3 min as required to a total of 10 mg; infusion may be necessary as its duration of action is short. Respiratory depression due to buprenorphine may not be responsive.

Opioid receptor antagonists. Different types:

pure antagonists, e.g. naloxone, naltrexone: antagonists at all opioid receptor subtypes. Methylnaltrexone is a peripherally acting mu antagonist, currently under investigation as a treatment for postoperative ileus.

pure antagonists, e.g. naloxone, naltrexone: antagonists at all opioid receptor subtypes. Methylnaltrexone is a peripherally acting mu antagonist, currently under investigation as a treatment for postoperative ileus.

agonist–antagonists: agonists at some receptors but antagonists at others, e.g.:

agonist–antagonists: agonists at some receptors but antagonists at others, e.g.:

– pentazocine: agonist at kappa and sigma, antagonist at mu receptors.

– nalorphine: partial agonist at kappa and sigma, antagonist at mu receptors.

– nalbuphine: as for nalorphine, but a less potent sigma agonist.

partial agonists, e.g. buprenorphine, meptazinol (mu receptors); may antagonise mu effects of other opioids (e.g. morphine).

partial agonists, e.g. buprenorphine, meptazinol (mu receptors); may antagonise mu effects of other opioids (e.g. morphine).

Their main clinical use is to reverse effects of opioid analgesic drugs, e.g. in opioid poisoning. Those with agonist properties are also used as analgesic drugs; some have been used to reverse unwanted effects of other opioids (e.g. respiratory depression) whilst still maintaining analgesia. In practice, this is very difficult to achieve. Also used in diagnosis and treatment of opioid addiction. Receptor-specific compounds have been developed for research and identification of receptor subtypes.

Opioid receptors. Naturally occurring receptors to morphine and related drugs, isolated in the 1970s. All are G protein-coupled receptors and activation results in opening of potassium channels and closure of voltage-gated calcium channels; this leads to membrane hyperpolarisation, reduced neuronal excitability and thus reduced nociceptive transmission. This effect is enhanced by reduction of cAMP by inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Found mainly in the CNS but also GIT; thought to be involved in central mechanisms involving pain and emotion. Three primary subgroups are now recognised (each subdivided into two or more putative subtypes), although others have been suggested in the past. More recently, data from transgenic mice lacking a single opioid receptor (e.g. MOP) have called into question the validity of further subtype classification.

– responsible for ‘supraspinal analgesia’; i.e. drugs act at brain level.

– agonists: all opioid analgesic drugs.

– partial agonists: buprenorphine, meptazinol (thought to be specific at mu1 receptors).

– antagonists: nalorphine, nalbuphine, pentazocine.

– activation has been experimentally shown to produce analgesia and cardioprotection.

– activation causes analgesia, miosis, sedation, different sort of dependence.

– responsible for ‘spinal analgesia’; i.e. drugs thought to act at spinal level.

Sigma receptors, previously considered opioid receptors, are not considered so now because the effects of their stimulation are not reversed by naloxone. They bind to phencyclidine and its derivatives, e.g. ketamine. All subtypes are antagonised by naloxone and naltrexone (mu and kappa more than delta).

Dietis N, Rowbotham DJ, Lambert DG (2011). Br J Anaesth; 107: 8–18

Opioids. Substances which bind to opioid receptors; include naturally occurring and synthetic drugs, and endogenous compounds.

Opium. Dried juice from the unripe seed capsules of the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. Contains many different alkaloids, including morphine (9–20%), codeine (up to 4%) and papaverine. Used for thousands of years as a recreational drug and for analgesia, especially in the Far East. Use as a therapeutic drug is rare now, purer drugs and extracts being preferred.

Oral rehydration therapy. Method of treating dehydration when mild or where facilities for iv fluid administration are lacking, e.g. in the community or developing countries. Particularly useful in gastroenteritis and in children; it has also been used in less serious burns. Various commercial mixtures exist; all contain glucose, the presence of which in the intestinal lumen facilitates the reabsorption of sodium ions and thus water. A simple version can be made by adding 20 g glucose (or 40 g sucrose since only half becomes available as glucose after ingestion), 3.5 g sodium chloride, 2.5 g sodium bicarbonate and 1.5 g potassium chloride per litre of water. Suitable solutions have been made by taking three 300 ml soft drink bottles of water and adding a level bottle capful of salt and eight capfuls of sugar.

Orbeli effect. Increase in strength of contraction of fatigued muscle following sympathetic nerve stimulation.

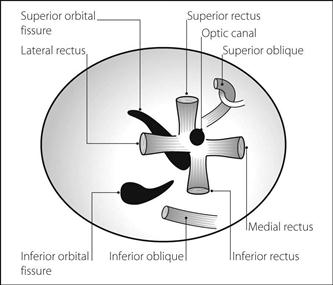

Orbital cavity. Cavity containing the eye and extraorbital structures. Roughly pyramidal with the apex posteriorly, its roof is formed by the orbital plate of the frontal bone (and lesser wing of the sphenoid posteriorly); its floor by the maxilla and zygoma; its medial wall by the frontal process of the maxilla and lacrimal bone anteriorly and orbital plate of the ethmoid and body of the sphenoid posteriorly; and its lateral wall by the zygoma and greater wing of the sphenoid (Fig. 123). Has three openings posteriorly:

superior orbital fissure: transmits the third, fourth and fifth (the three branches of the ophthalmic division) cranial nerves. Also transmits branches of the middle meningeal and lacrimal arteries, ophthalmic veins and sympathetic fibres.

superior orbital fissure: transmits the third, fourth and fifth (the three branches of the ophthalmic division) cranial nerves. Also transmits branches of the middle meningeal and lacrimal arteries, ophthalmic veins and sympathetic fibres.

inferior orbital fissure: transmits the maxillary nerve.

inferior orbital fissure: transmits the maxillary nerve.

– medial and lateral rectus: moves medially and laterally respectively.

See also, Peribulbar block; Retrobulbar block; Skull; Sub-Tenon’s block

Fig. 123 Frontal view of right orbital cavity

Oré, Pierre-Cyprien (1828–1889). French physician; Professor of Physiology at Bordeaux. Investigated blood transfusion and the effects of iv injection of drugs. Produced general anaesthesia with iv chloral hydrate in 1872, thus becoming the first to employ TIVA. Also treated tetanus with the drug.

Organ donation. Organs for transplantation may be donated by living subjects, e.g. kidney and bone marrow. The main issue concerns the undertaking of anaesthesia and surgery (with their attendant risks) by a healthy patient for altruistic reasons.

Many organs may be obtained from patients following diagnosis of brainstem death. They include kidney, heart, lung, liver, small bowel, pancreas, skin and cornea. Demand for organs outstrips supply. At present in the UK, members of the public identify themselves as potential donors by joining a national registry (an ‘opt-in’ system); in some countries (e.g. Spain, Austria, Belgium), an ‘opt-out’ system operates in which permission is assumed unless specified otherwise, and this has been proposed in the UK amongst considerable controversy.

Non-living patients have traditionally been considered unsuitable for donation for a number of relative reasons (e.g. systemic infection, age); with the relative shortage of organs, only HIV infection or Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease is considered an absolute contraindication and DCD now represents 35% of all donors in the UK.

Thompson JP, Murphy PG, Bodenham AR (2012). Br J Anaesth; 108 (suppl 1): i1–i119

Organe, Geoffrey Stephen William (1908–1989). English anaesthetist, born in India. A major influence on the development of anaesthesia in the UK and abroad, and involved in much research, particularly into the newly introduced neuromuscular blocking drugs. Professor of Anaesthesia at Westminster Hospital, London, and knighted in 1968.

Organophosphorus poisoning. An important worldwide cause of death due to acute poisoning, organophosphorus compounds are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, commonly used as insecticides but also manufactured as chemical weapons. One, ecothiopate, is used in glaucoma. Those used in insecticides are usually ester, amide or thiol derivatives of phosphoric or phosphonic acids, or their mixtures. They may be absorbed via the GIT, lungs or skin, and are rapidly distributed to all tissues, especially liver and kidney. Half-lives vary from minutes to hours, with metabolism by oxidation, ester hydrolysis and combination with glutathione, and excretion in faeces or urine.

peripheral enzyme inhibition:

peripheral enzyme inhibition:

– phosphorylation of acetylcholinesterase: may be irreversible depending on the compound involved. Features are those of cholinergic crisis and include muscarinic effects (bronchospasm, sweating, increased secretions, abdominal cramps, bradycardia, miosis) and nicotinic effects (muscle twitching, weakness, hypertension and tachycardia). Enzyme ‘reactivation’ may be induced by pralidoxime if administered within 24–36 h.

– phosphorylation of other enzymes, e.g. lipases, GIT enzymes.

myopathic effects: weakness may occur within 24 h of poisoning, with recovery taking up to 3 weeks. Muscle paralysis in humans may occur after recovery from the initial cholinergic crisis, 24–96 h after poisoning. Mainly affecting proximal muscles, it is thought to involve postsynaptic dysfunction at the neuromuscular junction.

myopathic effects: weakness may occur within 24 h of poisoning, with recovery taking up to 3 weeks. Muscle paralysis in humans may occur after recovery from the initial cholinergic crisis, 24–96 h after poisoning. Mainly affecting proximal muscles, it is thought to involve postsynaptic dysfunction at the neuromuscular junction.

CNS effects: anxiety, tremor, confusion, coma and convulsions may occur, with EEG abnormalities.

CNS effects: anxiety, tremor, confusion, coma and convulsions may occur, with EEG abnormalities.

Respiratory failure may result from peripheral weakness, central depression and increased tracheobronchial secretions.

Diagnosis is based on history, tolerance to atropine therapy, acetylcholine assay and measurement of blood and urine organophosphorus and metabolite levels.

supportive measures as for poisoning and overdoses in general. Care should be taken to avoid self-contamination.

supportive measures as for poisoning and overdoses in general. Care should be taken to avoid self-contamination.

Orphanin FQ (OFQ; nociceptin), see Opioid receptors

Orthopaedic surgery. Anaesthetic considerations may be related to:

– trauma: presence of other injuries, risks of emergency surgery (e.g. aspiration of gastric contents). Adequate resuscitation is important preoperatively, especially in the elderly, e.g. following fractured neck of femur (NOF). Cases with risk of infection, ischaemia or nerve damage are particularly urgent.

– musculoskeletal disease, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, connective tissue diseases, muscular abnormalities. There is a higher than normal incidence of MH susceptibility in young patients with musculoskeletal abnormalities.

– congenital malformations: may be accompanied by other system involvement, e.g. cardiac lesions.

– risk of massive hyperkalaemia following suxamethonium if neurological or muscle lesions are present.

– may involve repeated anaesthesia.

– use of methylmethacrylate cement.

– problems of specific procedures, e.g. kyphoscoliosis.

– regional techniques are particularly useful, e.g. hip surgery (arthroplasty, fractured NOF). Epidural and spinal anaesthesia are associated with fewer postoperative complications (including DVT) than after general anaesthesia, although mortality after fractured NOF is the same at 1 year.

– DVT and PE are common, especially after hip surgery; prophylactic measures should be taken. Fat embolism may occur after long bone fractures.

Oscilloscope. Device for displaying recorded signals, particularly those of high frequency and when analysis of their shape is required, e.g. ECG or arterial waveform. May also be used without the time-base to plot two signals with respect to each other, e.g. flow–volume loops.

The earliest oscilloscopes utilised a cathode ray tube to generate, accelerate and focus an electron beam on to a fluorescent screen, the beam visible as a bright dot. The signal potential was applied vertically across the beam, causing vertical deflection; a spatial reconstruction of the signal against time was then seen on the screen. The pattern could be made to persist by altering the characteristics of the fluorescent material, or by using a second cathode system. These are now termed analogue oscilloscopes, to distinguish them from the modern digital devices that have replaced them in medical practice. These utilise an analogue-to-digital converter to translate measured voltages (sampled at close, regular time intervals) into digital information that is then displayed on liquid crystal or light-emitting diode panels. Digital devices benefit from greater portability and the option to apply processing algorithms to recorded signals (e.g. for S–T segment analysis and detection of arrhythmias).

Oscillotonometer. Obsolete device for indirect arterial BP measurement, using one (upper) cuff for occluding the brachial artery and a second (lower) cuff for detecting pulsations, often incorporated into a double cuff. Both cuffs are inflated by hand to above systolic BP and then allowed to deflate slowly, using a lever to switch the dial to a sensitive ‘indicator’ mode by which increased and then decreased oscillations of the dial needle indicate systolic and then diastolic pressures respectively. At each of these points, the lever is used to return the indicator dial to a ‘recording’ mode to allow actual cuff pressure to be displayed. Has been replaced by automated devices, which employ similar principles but are more accurate, more reliable and easier to use.

Osmolality and osmolarity. Expressions of concentration of osmotically active particles in solution:

osmolality = the number of osmoles per kilogram solvent.

osmolality = the number of osmoles per kilogram solvent.

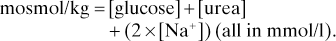

Osmolality of plasma is maintained at 280–305 mosmol/kg. Regulatory mechanisms include stimulation of thirst by osmoreceptors, baroreceptors and the renin/angiotensin system. Osmoreceptors also stimulate vasopressin release. Most contribution to plasma osmolality arises from sodium and its anions, glucose and urea; thus plasma osmolality may be estimated thus:

Alcohols, proteins, triglycerides and mannitol are not accounted for. Proteins usually contribute little since, despite their high concentration, few particles are liberated in solution because of their high mw.

Osmolality/osmolarity is determined by measuring ionic concentration with a flame photometer, measuring osmotic pressure or by employing the colligative properties of solutions (e.g. depression of freezing point, lowering of vapour pressure).

Urinary and plasma osmolality measurement is useful in investigating oliguria and renal failure.

See also, Fluid balance; Hyperosmolality; Hypo-osmolality; Osmolar gap; Tonicity

Osmolar gap (Osmolality gap). Difference between calculated and measured plasma osmolality. Normally 10–15 mosmol/kg; increased in the presence of low-molecular-weight substances not included in the formula for calculating plasma osmolality, e.g. alcohols, mannitol, glycine (in the TURP syndrome). May also be applied to urine osmolality, e.g. to indicate the presence of osmotically active substances such as ammonium ions.

Osmoreceptors. Cells in the anterior hypothalamus, outside the blood–brain barrier; respond to changes in plasma osmolality. Control thirst and secretion of vasopressin, possibly via separate groups of osmoreceptors.

Osmosis. Movement of solvent molecules across a semipermeable membrane from a dilute solution to a concentrated one, tending to equalise the concentrations on both sides. Thus water moves across cell membranes from the ECF following dextrose infusion, once the dextrose has been metabolised. Similarly, water in very hypotonic iv fluids may move into red blood cells after infusion, causing haemolysis.

Osmotic clearance, see Clearance, osmotic

Osmotic pressure. Pressure required to prevent movement of solvent molecules by osmosis across a semipermeable membrane.

See also, Oncotic pressure; Osmolality and osmolarity; Tonicity

Ouabain. Cardiac glycoside, poorly absorbed from the GIT and administered iv. Faster acting than digoxin; thus used when rapid action is required. 5% protein-bound, with half-life about 24 h, and excreted via kidneys and liver.

Outreach team. Concept similar to the medical emergency team, for improving identification and care of acutely ill patients throughout hospitals but especially on general wards. Usually nurse-led, but may also contain experienced medical and physiotherapy staff, often from ICUs, who may provide the following services: rapid response to acutely ill patients in general ward areas, critical care education for ward clinicians, facilitation of early admission to ICU/HDU, early recognition of patients for whom CPR and/or ICU admission is inappropriate and early post-ICU follow-up. Referral criteria include specific clinical scenarios or the results of early warning scores.

Goldhill DR (2005). Br J Anaesth; 95: 88–94

See also, Acute life-threatening events – recognition and treatment

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Condition caused by pharmacological stimulation of the ovaries in assisted conception programmes. Characterised by ovarian enlargement, pleural effusion and ascites; the latter in particular may be massive and unrelenting. Clinical features range from abdominal discomfort and swelling to hypovolaemic shock, hepatic impairment, acute kidney injury and acute lung injury. DVT may also occur. Mild symptoms occur in up to a quarter of cases of induced ovulation, whilst the severe form occurs in 1–2%.

Treatment is mainly supportive, with correction of hypovolaemia, careful attention to fluid balance and correction of metabolic disturbances. DVT prophylaxis is recommended. Abdominal paracentesis and pleural drainage are usually performed in severe cases; ultrafiltration and re-infusion of the ascitic fluid iv have been used to replace the protein-rich fluid otherwise lost.

Sansone P, Aurilio C, Pace MC, et al (2011). Ann N Y Acad Sci; 1221: 109–18

Overdoses, see Poisoning and overdoses

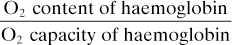

Oximetry. Determination of arterial O2 saturation of haemoglobin (SaO2) by measuring absorbance of light by blood. Described in 1934 using open blood vessels, and in 1940 using ear/hand probes, but the technique was cumbersome and difficult to perform. Modern pulse oximeters became widespread from the 1980s following advances in microchip technology, allowing manipulation of the recorded signal. Included in the UK/Ireland minimal monitoring standard for anaesthesia since 1987.

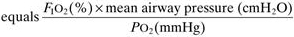

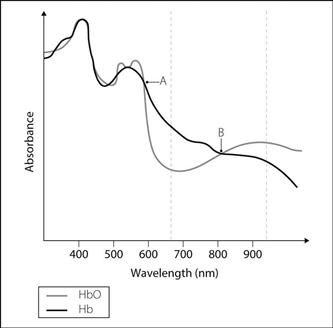

Relies on the principle that absorbance of light energy by haemoglobin varies with its level of oxygenation. Oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin (HbO and Hb respectively) have different absorbance spectra (Fig. 124). Isobestic points occur where the lines cross. Thus comparison of absorbance at different wavelengths allows estimation of the relative concentrations of HbO and Hb (i.e. SaO2). Earlier machines used two wavelengths, including one isobestic point as a reference; modern pulse oximeters may use two or more wavelengths, not necessarily including an isobestic point.

Oxpentifylline, see Pentoxifylline

Oxycodone hydrochloride. Opioid analgesic drug, described in 1916. Oral preparations are twice as potent as oral morphine due to higher oral bioavailability. Intravenous oxycodone is roughly equivalent to iv morphine.

Also available as suppositories (as the pectinate) by special order.

Oxygen. Non-metallic element existing as a colourless odourless diatomic gas (O2) in the lower atmosphere, and as triatomic oxygen (O3, ozone) and monatomic oxygen (O) in the upper atmosphere. The most plentiful element in the Earth’s crust (as opposed to nitrogen, the most plentiful in the atmosphere), it makes up 21% of air by volume. Discovered independently in 1771 by Scheele and Priestley, the latter calling it ‘dephlogisticated air’. Recognised as a gas by Lavoisier, who named it and explained the process of combustion. Combines with many other elements and molecules, and most abundant as water.

Essential for cellular respiration in animals and lower plants; higher plants take in CO2 and release O2 during photosynthesis. Boiling point is −183°C; melting point is −218°C; critical temperature is −118°C. Atomic weight is 16; specific gravity is 1.1 for liquid O2 and 1.4 for gaseous O2.

Commercial O2 is supplied in liquid form, manufactured by the fractional distillation of air. Available in hospitals by piped gas supply, O2 concentrators or in cylinders at 137 bar.

Oxygen cascade. Series of steps of PO2 from atmospheric air to mitochondria in cells:

humidified tracheal gas: 19.8 kPa (150 mmHg).

humidified tracheal gas: 19.8 kPa (150 mmHg).

alveolar gas: 14 kPa (106 mmHg): influenced by alveolar ventilation and O2 consumption.

alveolar gas: 14 kPa (106 mmHg): influenced by alveolar ventilation and O2 consumption.

arterial blood: 13.3 kPa (100 mmHg): influenced by

arterial blood: 13.3 kPa (100 mmHg): influenced by  mismatch.

mismatch.

capillary blood: 6–7 kPa (45–55 mmHg): influenced by blood flow and haemoglobin concentration.

capillary blood: 6–7 kPa (45–55 mmHg): influenced by blood flow and haemoglobin concentration.

Reduction in PO2 at any stage, e.g. due to hypoventilation, lung disease, causes reduction in subsequent steps, risking inadequate mitochondrial PO2 for aerobic metabolism (below the Pasteur point).

Oxygen concentrator. Device for extracting O2 from atmospheric air. Air is passed under pressure through a column of zeolite which acts as a molecular sieve, trapping nitrogen and water vapour whilst leaving O2 and trace gases. Nitrogen is removed by depressurising the column. Two columns are used, each alternatively adsorbing or expelling nitrogen. Produces a continuous supply of over 90% O2, suitable for most medical uses. Range in size from small units for home use to large ones supplying whole hospitals.

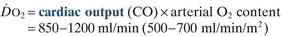

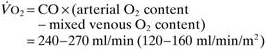

Oxygen delivery ( ). Calculated O2 flux. Used with O2 consumption (

). Calculated O2 flux. Used with O2 consumption ( ) to optimise treatment in critical illness.

) to optimise treatment in critical illness.

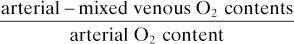

O2 extraction ratio has also been used (normally 22–30%):

Vincent JL (1991). Can J Anaesth; 38: R44–7

See also, Oxygen extraction ratio; Oxygen, tissue tension; Regional tissue oxygenation; Shock

Oxygen extraction ratio. Ratio of oxygen uptake ( ) to oxygen delivery (

) to oxygen delivery ( ), expressed as a percentage. Normally about 25%, it increases during periods of increased tissue demand, e.g. exercise. Also varies according to the tissue involved; thus myocardial extraction ratio is about 70%.

), expressed as a percentage. Normally about 25%, it increases during periods of increased tissue demand, e.g. exercise. Also varies according to the tissue involved; thus myocardial extraction ratio is about 70%.

Oxygen failure warning device. Device attached to (or incorporated into) the anaesthetic machine; designed to alert anaesthetists to failure of the O2 supply. Earlier models were often unreliable, e.g. Bosun device (required batteries to power a warning light, which could be switched off, and only operated when the N2O supply was connected).

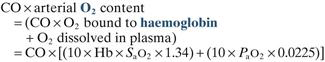

Oxygen flux. Amount of O2 delivered to the tissues per unit time.

where CO = cardiac output in l/min

Hb = haemoglobin concentration in g/dl

SaO2 = arterial O2 saturation of haemoglobin

0.0225 = ml of O2 dissolved per 100 ml plasma per kPa (0.003 ml per mmHg)

Normally 850–1200 ml/min, or 500–700 ml/min/m2 if cardiac index is used.

The tissues cannot utilise all of the transported O2: the last 20–25% remains bound to haemoglobin. Tissue O2 supply can increase during times of extra demand via increases in cardiac output, e.g. during exercise. If the O2 carrying capacity of blood is reduced (e.g. in anaemia) cardiac output must increase at rest in order to maintain O2 flux, and reserves are less. Myocardial depression during anaesthesia in this situation is thus particularly hazardous.

See also, Oxygen delivery; Oxygen extraction ratio; Oxygen, tissue tension; Oxygen transport

Oxygen, hyperbaric. O2 therapy at greater than atmospheric pressure, usually 2–3 atmospheres. Increases the amount of dissolved O2 in blood, according to Henry’s law. In 100 ml blood, 0.3 ml O2 dissolves at PO2 of 13.3 kPa (100 mmHg). Thus for 100% O2 at 3 atmospheres, dissolved O2 = 5.7 ml. Since haemoglobin is always saturated, even in venous blood, its binding capacity for CO2 and buffering capacity are reduced, and pH falls. The resultant hyperventilation may result in hypocapnia.