Nutritional support

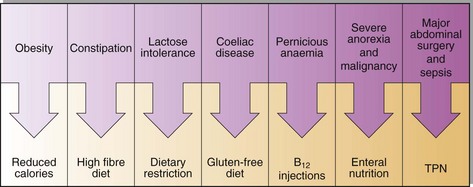

Nutritional support may range from simple dietary advice to long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN). In between is a whole spectrum of clinical conditions and appropriate forms of nutritional support (Fig 53.1). As we move to the right, climbing the scale of severity of disease, we increase the level of support and in so doing increase the need for laboratory back-up. The clinical biochemistry laboratory plays an important role in the diagnosis of some disorders that require specific nutritional intervention, e.g. diabetes mellitus, iron deficiency anaemia and hyperlipidaemia, but a much greater role is played in the monitoring of patients receiving the different forms of nutritional support.

What do patients need?

Energy

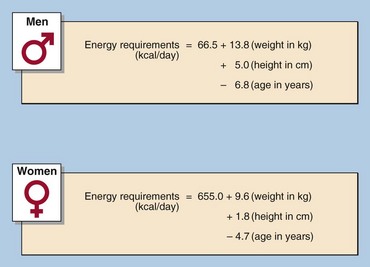

The basal energy requirements can be roughly calculated by using the basal metabolic rate (BMR) formula (Fig 53.2). The Harris-Benedict equation uses the calculated BMR and applies an activity factor to it to calculate the total daily energy expenditure. However, in the case of acutely ill or malnourished patients, the energy requirements are adjusted to account for the pre-existing weight loss and ongoing catabolic stresses as well as increased requirements in the hope of inducing an anabolic state. The principal energy sources in the diet are carbohydrates and fats. Glucose provides 4 kcal/g while fat provides 9 kcal/g. The entire calorie load may be administered using carbohydrates, but prescribing a mixture of carbohydrates and lipids is more physiological and serves to reduce the volume of the diet. This is important in both enteral tube feeding as well as in parenteral nutrition.

Nitrogen

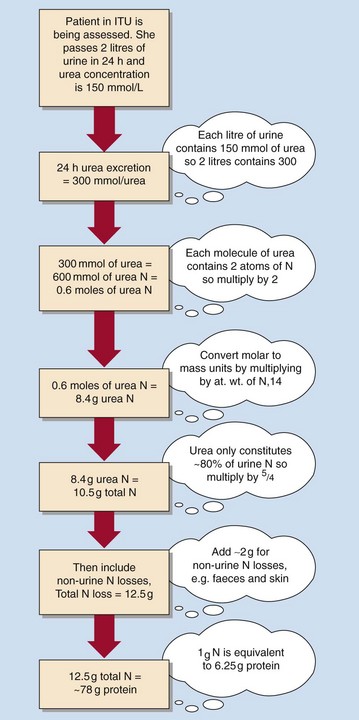

The reference nutrient intake (RNI) for protein for the average adult is 0.75g/kg body weight/ day. Basic nitrogen requirements can be calculated using 0.17g/kg body weight/day and converted to protein in g/day; 1g of nitrogen is equal to 6.25g of protein. Urinary nitrogen excretion can be measured using urinary urea nitrogen excretion from a 24-hour urine sample (Fig 53.3). This can be a more precise estimate of nitrogen requirements, but is reserved for specific patient groups and would be inappropriate to use in renal and metabolically stressed patients.

How should they receive it?

Care must be exercised to prevent over and under feeding. Patients may be fed in the following ways:

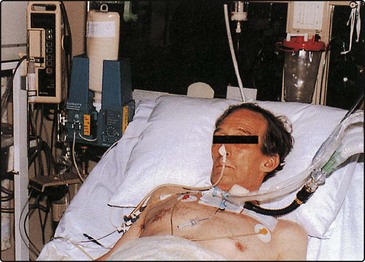

Oral feeding should be used whenever possible. Tube feeding (Fig 53.4) involves the use of small bore nasogastric, nasoduodenal and gastrostomy tubes. Defined diets of homogeneous composition can be continually administered. Tube feeding in this way bypasses problems with oral pathology, swallowing difficulties (e.g. after a stroke) and anorexia. Even patients who have had gastric surgery can be tube fed postoperatively if a feeding jejunostomy is fashioned during the operation distal to the lesion. However, tube feeding also presents mechanical problems in terms of blockage or oesophageal erosion. Gastrointestinal problems such as vomiting and diarrhoea, and metabolic problems can be minimized by the gradual introduction of the feeds and are rarely contraindications to enteral feeding. The problems associated with parenteral nutrition are even more severe and are discussed on pages 108–109. It should be noted, however, that the vast majority of patients can be fed very successfully either orally or with enteral tube feeds.