16 Nutritional Deficiencies

Assessment of a pediatric patient’s nutritional status includes evaluation of the child’s current and past medical problems, dietary intake, growth parameters, physical examination, and often laboratory tests. Establishing normal growth and development, prevention, and early identification of nutritional deficiencies is the goal in assessing a patient’s nutritional status. When evaluating a patient for specific nutritional deficiencies, clinical findings as well as laboratory data may be helpful. Children with mild nutritional deficiencies often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms that are discussed in Chapter 17. However, when severe deficiencies are present, the presentation will be more pronounced, as described in this chapter. Serum albumin can be used to determine long-term nutritional status, and serum prealbumin provides assessment of the adequacy of short-term dietary intake (see section on malnutrition for further information). A complete blood count (CBC) with red blood cell (RBC) indices can be used to identify deficiencies of iron, folate, vitamin B12, and anemia of chronic disease. Laboratory assessment of fat-soluble vitamins (A, E, and D) is more easily measured than are water-soluble vitamins.

Deficiencies

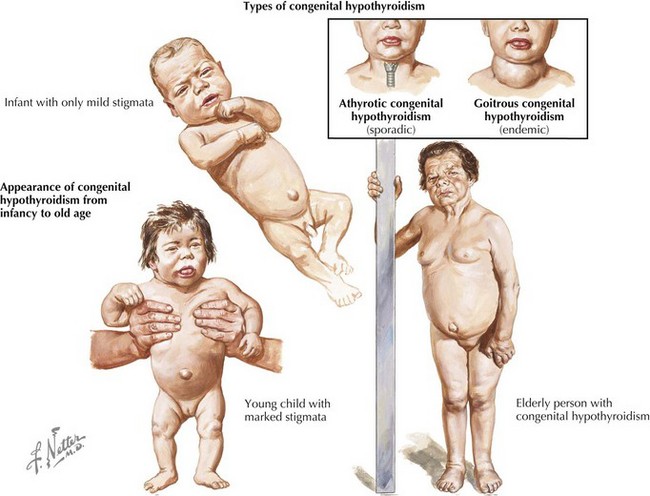

Iodine

Iodine is an essential component of thyroid hormone that is crucial for growth and development. Iodine is absorbed through the intestines in the form of iodide and is then taken up by the thyroid gland for incorporation into thyroxin (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Before the iodization of salt in 1920, iodine deficiency was endemic in the United States, and it is still the most common preventable cause of mental retardation worldwide. A deficiency of iodine is the most common cause of goiter, an enlargement of the thyroid gland, which, if large enough, may produce symptoms such as hoarseness or dysphagia as a result of local compression. Iodine deficiency and subsequent thyroid hormone deficiency can manifest with symptoms of hypothyroidism, such as weight gain, fatigue, and constipation. The most severe consequence of iodine deficiency is congenital hypothyroidism (mental retardation, deaf-mutism, gait abnormalities, and short stature), which can be prevented by adequate iodine intake both during pregnancy and early infancy (Figure 16-1).

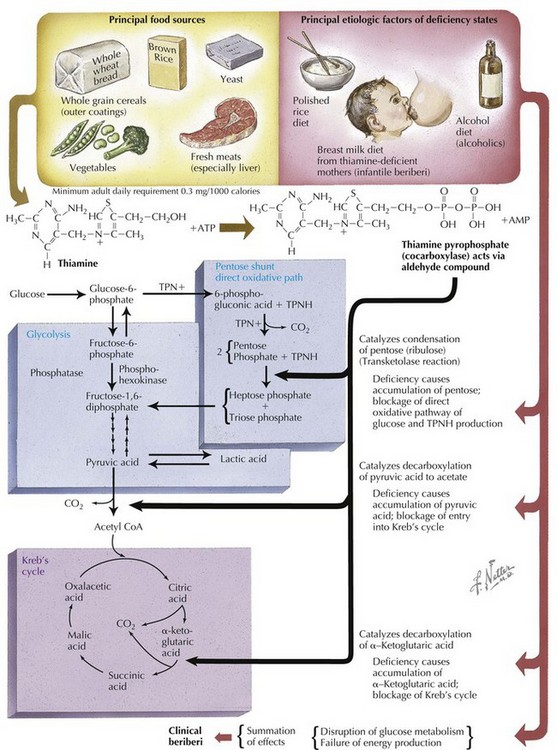

Vitamin B

The role of the vitamin B complex is varied but primarily affects the skin and muscle systems. Deficiency of vitamin B1 (thiamine) causes beriberi, the symptoms of which include weight loss, extremity pain and weakness, emotional disturbances, and cardiac abnormalities (Figure 16-2). Korsakoff’s syndrome, which is characterized by an irreversible psychosis, is a consequence of chronic thiamine deficiency. Lack of vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is associated with dermatologic findings such as cheilosis, angular cheilitis, glossitis, and seborrheic dermatitis and with congenital abnormalities such as cleft lip and transverse limb deficiency. Vitamin B3 (niacin) is a key component in required coenzymes in the body, and its deficiency may lead to pellagra, diarrhea, dermatitis, and dementia. The symptoms of vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiencies include paresthesias, depression, and fatigue, although lack of these vitamins is uncommon. In infants, deficiency of pyridoxine may cause seizures that are refractory to antiepileptic drugs. Deficiency of vitamin B7 (biotin) is rare and has been linked to growth impairment in infants.

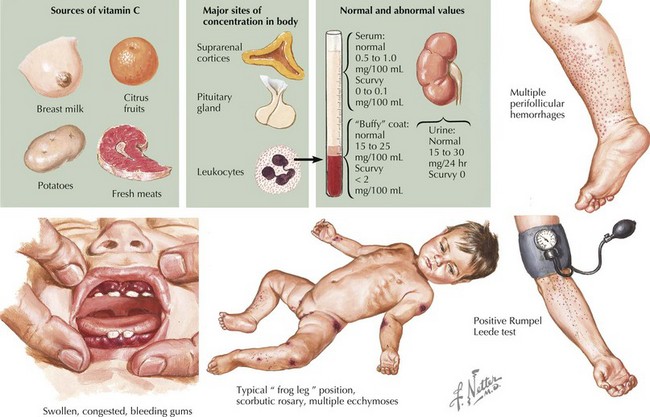

Vitamin C

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is not synthesized by humans and therefore must be obtained through the diet in the form of fruits and vegetables. Vitamin C deficiency manifests as scurvy with symptoms such as gingival hemorrhages, petechial rash, and ecchymosis caused by defective collagen synthesis of blood vessel walls. Children with vitamin C deficiency may also present with bony tenderness, pseudoparalysis, and poor wound healing. Diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency can be made clinically by assessing physical signs and symptoms as well as characteristic radiologic findings, such as costochondral beading known as scorbutic rosary (Figure 16-3).

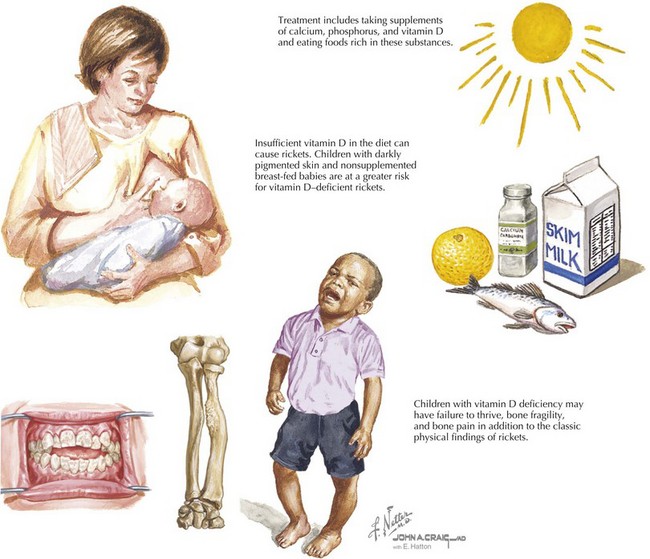

Vitamin D

Vitamin D plays a major role in bone mineralization by regulating the levels of calcium and phosphorus in the body through absorption in the intestines and reabsorption in the kidney. Whereas vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) is provided in the diet, vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is produced in the skin when 7-dehydrocholesterol reacts with ultraviolet B (UVB) light. Foods naturally rich in vitamin D include eggs and fatty fishes, although foods such as milk, cereal, and bread are often fortified with vitamin D. After vitamin D is produced in the skin or consumed in food, it is converted in the liver and kidney to 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), the physiologically active form of vitamin D known as calcitriol. Vitamin D deficiency may result from a lack of exposure to UVB radiation; inadequate intake; fat malabsorption; liver or kidney disease, which can impair its conversion to active metabolites; and rarely, genetic disorders. Deficiency is most commonly seen in breastfed infants with inadequate vitamin D supplementation. Dark-skinned children are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency because increased amounts of melanin in the skin reduce the body’s ability to produce endogenous vitamin D in response to sunlight exposure. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines published in 2008 recommend supplementation of 400 IU/day vitamin D for all infants. The AAP also recommends that older children and adolescents who do not obtain 400 IU/d through diet should take a 400-IU vitamin D supplement daily (Figure 16-4).

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243-260.

Kleinman RE: Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition, 2004, Elk Grove Village, IL.

Misra M, Pacaud D, Petryk A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children and its management: review of current knowledge and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):398-417.