Chapter 2 Nutritional assessment and therapies

With contribution from Dr Antigone Kouris-Blazos

Introduction

The importance of nutrition in general medical practice has paralleled the increasing prevalence of lifestyle related disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. In fact, alongside dermatology and psychological disorders, nutritional disorders are among the most common problems encountered by doctors and there is pressure for the general practitioner to provide competent nutritional assessment, diagnosis and therapy.1 It has been estimated that over 70% of patients seen in general practice are at high risk of having or developing a nutritional deficiency and many patients will exhibit symptoms suggestive of nutritional inadequacy or imbalance which is contributing to their illness.2, 3

The Australian National Health Survey in 2004–5 reported that 86% of Australians between 18–64 years do not consume the recommended 5 serves of vegetables each day and 46% do not consume the recommended 2 serves of fruit each day.4 In 2008 rising petrol and food prices (especially for fresh produce but not for processed/take away foods) were reported to potentially affect shopping trends with less fresh produce being purchased.5 Furthermore, the costs of healthy foods such as bread and milk is rising far greater than the cost of nutrient poor energy dense foods (such as cakes, soft drinks and biscuits), which will impact on food choices and the diet in lower socioeconomic groups.6

This may be further compounded by emerging evidence from the UK and US (Australian data lacking) that there has been declining levels of minerals in our fruit and vegetables over the last 50 years, especially for magnesium dropping by about 45% (see page 23 ‘Dietary history and assessing food and nutrient intake’). Markovic and Natoli report paradoxical nutrient deficiencies such as zinc, iron, vitamin C and D and folate in the obese and overweight due to eating high-energy foods that are also high in saturated fats, salt and sugar, with poor nutrient content.7 The authors note that this condition is under-recognised and therefore not treated. The Public Health Association of Australia released a report in 2009 ‘A Future for our Food: addressing public health, sustainability and equity from paddock to plate’ outlining the urgent need for Australian food policy to encourage food choices that are environmentally sustainable and address the re-emergence of nutrient-deficiency related diseases.8

The Australian dietary guidelines and core food groups are currently undergoing revision. The Public Health Association of Australia would like to see the new guidelines address the re-emergence of nutrient-deficiency related disease and food sustainability. Specific recommendations include: reduced total intake of animal products; reduced reliance on ruminant meat; promotion of sustainable proteins, especially legumes, nuts, eggs and chicken; promotion of seasonal fruit and vegetables, legumes and grains that are grown using production methods appropriate to the region. The report highlights that shifting less than 1 day per week’s worth of calories from red meat and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or legume-based diet achieves more green house gas reduction than buying all locally sourced food. In addition, consuming less meat and more plant-based foods may be 1 type of measure that will lead to increased sustainability and reduced environmental costs of food production systems.8

The Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey also highlights the growing epidemic of obesity in children — estimated at 17% of children considered overweight and 6% obese in Australia — with poor quality diets with significant nutritional shortfalls, particularly vitamin D, E, iodine and iron.9

Suboptimal intake of vitamins from diet is common in the general population, particularly children and the elderly, and a risk factor for chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, neural tube defects, colon and breast cancer, osteopenia and fractures.10

Nutritional assessment will identify the high-risk patient (see Table 2.1) for nutrient inadequacies or excesses which in turn will contribute to a nutritional diagnosis. Once the diagnosis is made it is then possible to put in place the nutritional therapy of the patient.

Table 2.1 Identifying patients at high risk of nutrient deficiency or insufficiency

(Source: adapted from Wahlqvist M, Kouris-Blazos A. Nutrition — is diet enough? J Comp Med 2002: 46)11

Nutritional assessment is based on information gathered from:

Table 2.2 Presentations and signs (can include) to consider with specific vitamin deficiencies (rare or sub-clinical deficiency in Western populations)

| Micronutrient | Signs |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A | |

| Vitamin B1 | |

| Vitamin B2 | |

| Vitamin B3 | |

| Vitamin B6 | |

| Vitamin B12 | |

| Vitamin B complex/folate | |

| Vitamin C | |

| Vitamin D | |

| Calcium (Ca) and/or magnesium (Mg) | Positive Chvostek sign |

| Iron (Fe) | Koilonychia, leucoplakia, Plummer–Vinson syndrome |

| Zinc (Zn) | Acne, stretch marks, white spots on nail |

| Iodine (I) | Weight gain |

Medical history

Signs and symptoms of nutritional deficiencies

Clinical symptoms and anthropometric measurements will provide further clues to the nutritional puzzle. However, symptoms (manifestations reported by the patient) and signs (observations made by a clinician) can occur late in the development of the nutritional problem. Thus diagnosis of a nutritional deficiency cannot usually be made solely on the basis of a clinical examination. This is mainly because many nutrition-related signs and symptoms are non-specific and can occur for non-nutritional reasons. Usually the presence of a group of related clinical signs and symptoms is a better indication than a single sign or symptom.12 For example, the finding of follicular hyperkeratosis isolated to the back of a patient’s arms is a fairly common, normal finding. On the other hand if it is widespread on a person who consumes little fruit and vegetables and smokes regularly (increasing vitamin C requirements) vitamin C deficiency is a possible cause. Not surprisingly, the tissues with the fastest turnover rates are the most likely to show signs of nutrient deficiencies or excesses e.g. hair, skin and lingual papillae (an indirect reflection of the status of the villae of the gut)13 (see Tables 2.2 and 2.3 for clinical signs and symptoms of possible nutritional deficiencies).

A thorough medical and nutritional history, together with a thorough physical examination is necessary to detect nutrient deficiencies (occasionally this may be subtle i.e. nutritional insufficiency). When taking a nutritional history, if limited by time, ask patients to recall what they ate and drank in the last 24–48 hours and/or ask them to bring a 1-week food diary at their next consultation. If time permits, then a more extensive dietary assessment would be helpful as discussed under Dietary history and assessing food and nutrient intake in this chapter. Examples of symptoms suggestive of nutrient deficiencies include gum bleeding (vitamin C), numbness of feet (folic acid and B1 deficiency), night blindness (vitamin A), poor immunity and recurrent infections (vitamins A, C, D and zinc), poor appetite (B group vitamins and zinc), muscle cramps (calcium, magnesium), tremor (magnesium), poor memory (B group vitamins, folic acid and various minerals e.g. magnesium), loss of libido (B group vitamins, folic acid), tiredness (any nutrient), mood disorders (B group vitamins, vitamin C and zinc), poor wound healing (protein, zinc, vitamin C), sore tongue (several B group vitamins) and loss of taste (zinc). Physical examination of the patient may identify a number of signs suggestive of nutrient deficiency (see Tables 2.2 and 2.3).

Table 2.3 Clinical symptoms and signs of nutrient deficiencies/insufficiencies

| Clinical symptoms and signs | Consider low intake/deficiency (may warrant blood/urine/faeces testing) |

|---|---|

| HEAD | |

| appetite poor | Zni, v, Mgiii, Feiii, B1vi, B3vi, folatevi, excess vit Ai |

| nausea (esp with fatty foods) | B3vi |

| fatigue/tiredness/irritable | B6vi, B12vi, folatevi, Zni, v, vi, vit Cvi, Feiii, vi, chromium (Cr)vi, thyroid, excess vit Av, proteinvi |

| sugar cravings/hyperglycaemia | insulin resistance, Mg, Criii, v, vi, Zn, vit E |

| moody/depressed | proteinvi, B1vi, B3iii, B6iii, vi, B12vi, vit Cvi, Mgvi, Zniii, iodine, thyroid, vit D |

| anxiety/agitation | Crvi, Mgvi, vit Dvi |

| migraine | B2vi, coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) |

| headache | B3iii, B12vi, folatevi, Feiii, Mg if cervicocranial, excess vit Ai, iii |

| sleep disturbance | B6vi, Mgvi, vit Cvi |

| sleep onset delay | vit Dvi |

| poor dream recall | B6vi |

| insomnia/restless sleep | vit Dvi, Cavi, B3iii |

| non-refreshing sleep | Mgvi |

| night sweats-back of head/scalp | vit Dvi |

| low libido | Fe (women) iii, Zn (men), low testosterone, thyroid |

| impaired memory/cognition/dementia | B1iv, vi, B12iii, iv, vi, B3iii, iv, v, folateiv, vi, Fevi, Znvi, iodine |

| HAIR/SCALP | |

| hair thinning/loss/alopecia | proteiniv, B2vi, EFAvi, Zniii, vi, Fevi, Biotini, iii, v, vi, excess vit Aiii, excess selenium (Seiii) thyroidi, iodine |

| dry dull hair | essential fatty acid (EFA)vi, vit Avi |

| easily plucked hair | proteiniv |

| dry coarse/brittle hair | proteiniv, biotiniv, Fevi, Zni, vi, Iodine, hypothyroid, EFAvi, excess vit Ai, iii |

| depigmentation/dyschromotrichia | copper (Cu)i, Sei |

| hair growth arrest | Zni |

| diaphoresis of scalp (night) | vit Dvi |

| dry flaking hair and scalp | vit A, Zn, Se |

| dandruff | Znvi, Mgvi, biotinvi, Se |

| prematurely graying hair | Cuvi, Biotinvi, vit B12iii, vi |

| coiled/cork screw hairs | vit Ciii (hair shaft flat instead of round in cross section) |

| EYES | |

| tearing/burning/itching | vit B2v |

| dark/crimson under eye circles | Fe, allergyvi, liver problems |

Important note: The list in Table 2.3 is not definitive and is based on combined clinical experience and scientific evidence. Assessment and treatment should be based on your own clinical judgment (i.e. dietary history and physical examination) and confirmed with pathology testing. Symptoms may also occur from other non-nutritional related diseases.

i McLaren DS. A Colour Atlas and Text of Diet-Related Disorders. 2nd edn. London England: Wolfe & Mosby — Year book Europe Ltd, 1992.

ii Medscape. Examining the Fingernails When Evaluating Presenting Symptoms in Elderly Patients. Online. Available: www.medscape.com (accessed 7 Aug 2008).

iii McLaren DS. Clinical manifestations of human vitamin and mineral disorders: a resume. In: Shils M, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross C. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th edn. Williams & Wilkins, 1999;485–503.

iv Newton MJ, Halsted CH. Clinical and functional assessment of adults. In: Shils M, Olson JA, Shike M, Ross C. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th edn. Williams & Wilkins, 1999;895–902.

v Heimburger DC, Ard JD. Handbook of Clinical Nutrition. 4th edn. Mosby Elsevier 2006.

vi Sydney-Smith M. Nutritional Assessment. J Comp Medicine 2006; Jan-Feb 28–40; and Nutritional Assessment Workshop Seminar slides, March 2008.

Anthropometry

Anthropometry is a measurement and study of the human body and its parts and capacities and can provide information on body muscle mass, fat reserves and fat distribution. Unintentional weight loss during illness often reflects loss of lean body mass, especially if rapid and not caused by diuresis. Body mass index (BMI) alone is not ideal in determining health risk because it does not reflect the amount of muscle or distribution of fat mass. The waist circumference is a good indicator of abdominal obesity but it does not differentiate between visceral/internal fat (the one linked to chronic diseases) and the more inert subcutaneous abdominal fat. Convenient and inexpensive electrical impedance devices are increasingly being used by clinicians to determine muscle mass, fat mass, visceral fat and body water. When assessing health risks associated with a patient’s weight, it may be useful to remember that higher weight in the elderly has been associated with lower mortality risk — staying in the ‘normal’ BMI range during young adulthood is recommended but slowly gaining weight during the elderly years does not seem to pose a health risk. On the other hand, obesity during young adulthood and being underweight during the elderly years leads to higher mortality rates.14 Furthermore, if a patient does a lot of exercise but is still overweight this poses a lower mortality risk than being slim and unfit.15 There is also emerging evidence of a subgroup of healthy obese that could be genetically determined or could relate to the dietary pathway in becoming overweight. For example, becoming overweight on a Mediterranean diet may not pose the same health risk as becoming overweight on a Western diet. This possibility has been identified in elderly Greek migrants in Australia that despite being overweight had lower mortality rates than their leaner Anglo-Celtic counterparts.16

Medications

A medication history may reveal possible drug nutrient interactions that lead to nutrient deficiencies or excesses. (See Chapter 37, Herb–nutrient–drug interactions.)

Dietary history and assessing food and nutrient intake

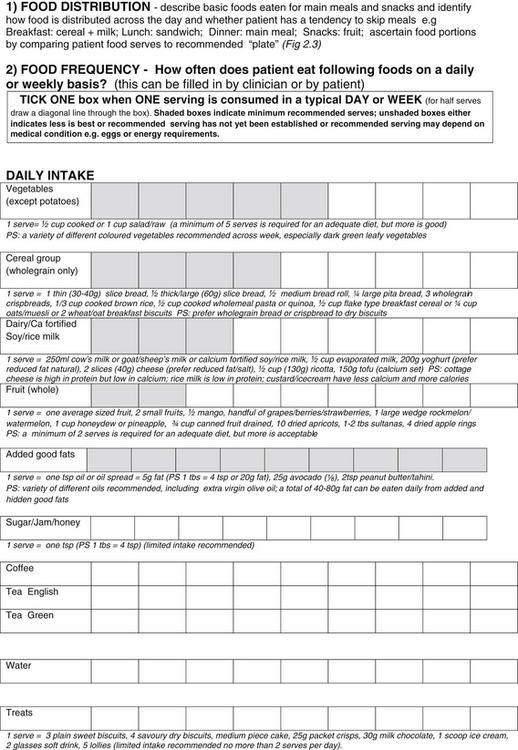

Figure 2.1 Taking a dietary history from your patient18

Copyright: Kouris-Blazos A 2010; adapted from Kouris-Blazos A & Wahlquist ML, HEC Healthy Eating Pyramid 2001, www.healthyeatingclub.org, 2001

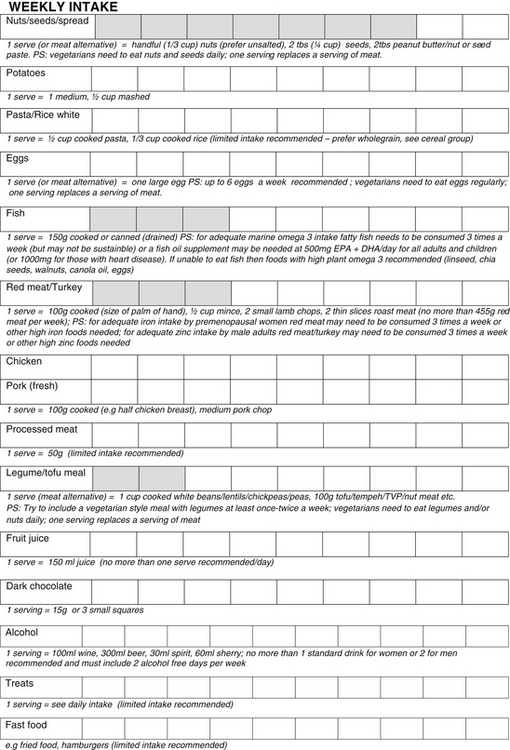

Figure 2.2 Estimating portion sizes19

Copyright Abbott Nutrition, http://glucerna.com/smart_nutrition/npwd.aspx

A general dietary history from a patient can be obtained within 5–10 minutes. A more detailed dietary history using the information as in Figure 2.1.

Note: Serving food from a smaller plate (e.g. from a 30cm plate to a 25cm plate) can result in about 22% fewer calories being served as long as vegetable intake is not reduced (www.smallplatemovement.org).

Assessing food intake and nutrient intake

The interest in the Mediterranean diet was reignited in the 1990s when a Greek-Australian team of researchers showed that adhering to the principals of a Mediterranean food pattern conferred longevity in people aged over 70,21 especially when legumes were consumed.22 The Mediterranean diet represents the dietary pattern that has been widely reported to be a model of healthy eating23 that contributes significantly to a favourable health status24, including prevention of diabetes,25 cancer,26 cardiovascular and heart disease27 and even obesity/weight loss.28

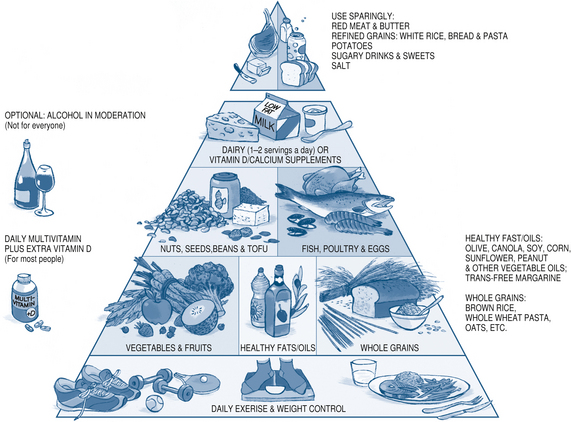

Figure 2.4 The Healthy Eating Pyramid29

Copyright © 2008. For more information about The Healthy Eating Pyramid, please see The Nutrition Source, Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, http://www.thenutritionsource.org, and Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy, by Walter C Willett, MD and Patrick J Skerrett (2005), Free Press/Simon & Schuster Inc.

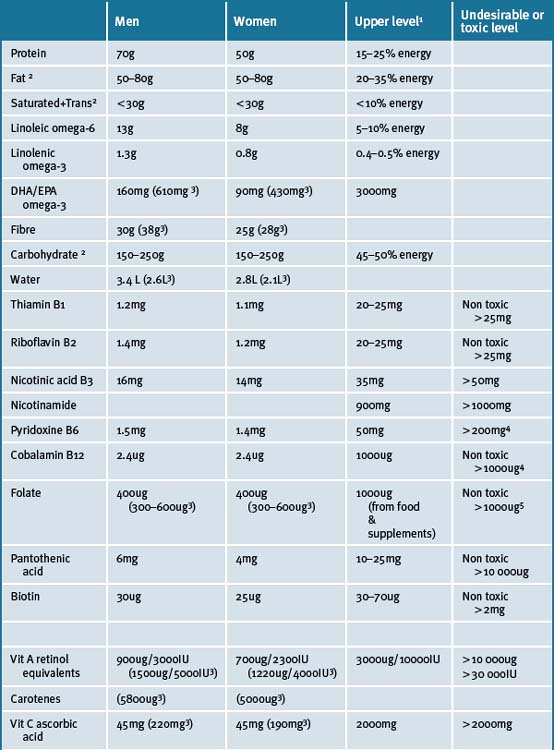

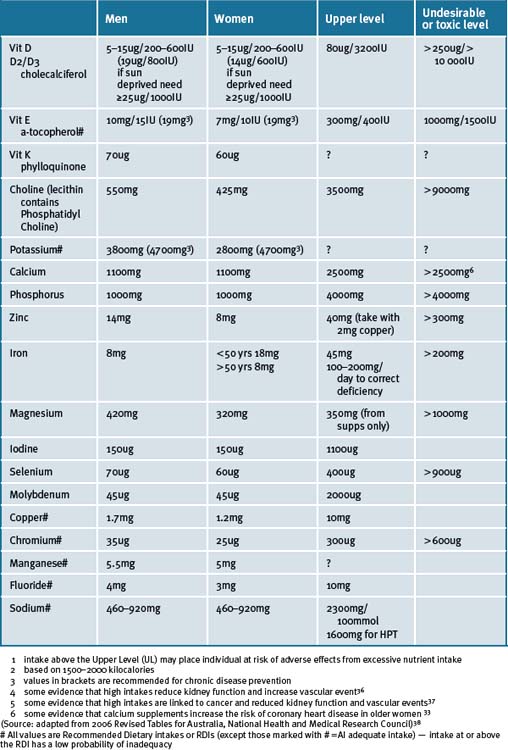

The food serves calculated from the dietary history can be compared to the recommended food serves (shaded boxes in Fig 2.1). The closer the patient’s intake is to the recommended daily servings for meat and alternatives, fruit, dairy, cereals, and vegetables the more nutritionally adequate it will be. To investigate the intake of particular nutrients, food composition tables or lists of good food sources of nutrients can be used (see Appendix 1). The adequacy of energy and nutrient intakes can then be compared to the recommended dietary intake (see Table 2.4 and Figure 2.5).

When the food and nutrient data is combined with other sources of information (e.g. clinical signs, laboratory tests) it can help confirm or rule out the possibility of suspected nutritional problems. A sufficient intake of a nutrient does not guarantee adequate nutrition status for an individual (e.g. medication or chronic diarrhoea may be increasing excretion of minerals) and an insufficient intake does not always indicate a deficiency, but such findings warn of possible problems. A variety of computer programs and patient questionnaires are available that permit rapid estimation of nutrient intake. These can be completed before or after the consultation, with the aid of practice staff. However, many of these nutrient analysis programs are based on food composition tables that have been periodically updated for some foods but not all foods. For instance, the nutrient composition data for Australian fruits and vegetables is over 20 years old in the Australian food composition tables, therefore calculated nutrient intakes using these programs may not reflect actual intake.

There is emerging evidence from the UK and USA that there have been declining levels of many nutrients in fruit and vegetables over the last 50 years with magnesium levels dropping by 45%, calcium and iron levels dropping by 20%, copper by 80%, vitamin C by 20% and riboflavin by 40%. These changes have been linked to changes in soil quality and plant cultivars having a higher water content (referred to as the dilution effect) suggesting that crop yield may have been favoured over nutrient content.30, 31, 32 Many Australians are not eating the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables and these data suggest we may need to eat even larger serves of fruit and vegetables!

Laboratory tests

The laboratory test will, to some extent, help the clinician confirm their suspicions and assist them in reaching a nutritional diagnosis. Sample nutritional testing may include those tests detailed in Table 2.5.3, 34

∗ Skin prick for allergies and elimination diet and oral re-challenging test for food intolerances are considered gold standard.

There are limitations in using plasma, serum or cellular conentrations of nutrients as these are subject to homeostatic control, tend to reflect very recent uptake or supplementation and not longer term nutritional status. Supplements should be ceased a few days before blood testing.34

Nutritional therapy and micronutrients

Recommended daily intake

Micronutrients are nutrients, such as vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids that are required by the body in small quantities (usually less than 1g/day),35 as opposed to macronutrients that include proteins, carbohydrates and fats. This topic has been a controversial and highly debated area amongst leading nutritionists, but there is an increasing body of scientific evidence to support the use of micronutrients as therapeutic agents. There is no doubt in anybody’s mind that our natural source of micronutrients should be from food. A diet of fresh fruit, vegetables, whole-grains, meats, legumes, raw nuts and seeds, and dairy foods (if tolerant to cow’s, goat’s or sheep’s milk) should provide all of the necessary nutrients. However, as discussed, it is not always possible for individuals to obtain their required daily allowance of nutrients from food.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) updated its recommended daily intake of nutrients in 2006; the first time in 15 years.39, 33 The update brings with it a new set of definitions. The recommended intakes are now referred as ‘Nutrient Reference Values’ (NRV). ‘Estimated Average Requirements’ (EAR) was established for all nutrients, which is the level estimated to meet the requirements of half of the healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group. If the data were normally distributed and sufficiently robust to calculate an EAR then a Recommended Dietary Intake (RDI) was defined as the EAR plus 2 standard deviations; that is, most EAR values are 20% less than the RDIs. When there were insufficient or inconsistent data to calculate an EAR, an Adequate Intake (AI) was set. The AI is defined as the median intake of a given nutrient as obtained from the National Nutrition Surveys of Australia and New Zealand. Furthermore, an Upper Limit (UL) was set for the first time for all nutrients that included intake from all sources and was based on the possibility of adverse effects. The NRVs also include a recommendation for an Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range or AMDR expressed in terms of total energy consumed. The AMDR for protein has increased allowing for a higher intake than previously recommended (up to 25% energy intake). There is also the Suggested Dietary Target (SDT) for chronic disease prevention for many micronutrients, fibre and omega-3 fatty acids for which there is evidence that intakes higher than EAR, RDI or AI may confer a health advantage. In the revised NRVs, the RDIs for the following nutrients increased: iron (for women only); calcium, zinc (for men only); magnesium; and B group vitamins. The RDI for vitamin E was changed to AI (and an SDT was set) because the key evidence, published in the early 1960s, does not allow for a valid analysis of the vitamin E dose-response curve.

A number of population studies and surveys have shown that the majority of people in the community fail to meet RDI levels for many common nutrients.43, 41 For instance, the Commonwealth Department of Health, 43, 41 following a national dietary survey in 1983 on adults and in 1985 on children, concluded that there were problems of excess in the average Australian diet, particularly of sugar and fat intake, and a high prevalence of obesity. The studies indicated that a significant proportion of the population did not reach RDI levels. This was seen mostly in females, and in the Asian and Southern European population. Micronutrients that these populations were mostly deficient in included vitamins A, calcium, zinc iron, and calcium.

A survey of children and teenagers in 2007 continues to highlight the nutritional shortfalls of the diets of Australian children and teenagers, with less than 5% meeting the guideline for recommended vegetable intake and only 1% of teenagers consuming 3 serves of fruit daily when fruit juice was excluded (24% met the recommendation when juice was included) and egg intake was low at less than 2 eggs per week.42 The study also reported the following average percentages of children aged 9–16 years not achieving the minimal EARs for key nutrients: calcium (60%); folate (15%); vitamin A (12%); magnesium (30%); zinc (10%); iodine (10%); and iron (3%). However, when intakes were compared to RDIs (or optimal intake) the percentage of children not achieving RDIs was much higher than those for EARs (since RDIs are about 20% higher than EARs).

Nutrient deficiency

There are various reasons for nutrient deficiencies occurring. One factor is over-consumption of processed and packaged foods, causing:40

Nutritional deficiencies are becoming more common because of emerging food insecurity and the changing quality of the food supply, especially iodine, selenium, magnesium, zinc, and vitamin D. Special cultivars of plants that can absorb and bind organically greater amounts of these nutrients might be the answer in addressing nutrient deficiencies in plants rather than food fortification with micronutrients. Apart from food processing, risk factors for micronutrient deficiency also includes the following:43

Megadoses versus multivitamins

A Cochrane review based on a meta-analysis of 68 randomised primary and secondary prevention trials (n = 232 606) that tested antioxidant supplements concluded that high doses of vitamins A, E and b-carotene (but not vitamin C or selenium) can significantly increase all-cause mortality when given singly or with other antioxidant supplements.44 This review, however, focused on antioxidant vitamins used at high doses rather than lower dose multivitamins. Furthermore, the review looked at 815 antioxidant trials but included only 68 of them in its analysis. Two excluded from this review (published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute and the Lancet) found substantial benefits and reduced mortality from intake of antioxidant supplements. If these 2 large studies had been included, none of the reported effects on increased mortality would have been significant, with the exception of the effects of beta-carotene.

The research on multivitamin supplement usage is more positive and has prompted many nutrition experts to rethink their stance on this issue (see below). Several studies have shown taking low dose multivitamins can reduce health risks such as all-cause mortality, ischaemic heart disease and cancer in men but not in women (RR 0.63 in men versus RR 1.03 in women, in 13 000 French adults taking a single capsule daily multivitamin over a 7.5 year period), especially where the diet is of poor quality and lacking in nutrient-dense foods.45 A study on people (n = 1056) using (1) multiple supplements (2) a single multivitamin supplement and (3) non-users of multivitamins produced some interesting findings. More than 50% of the multiple supplement users took a multivitamin, B complex, vitamin C, carotenoids, vitamin E, calcium/vitamin D, fish oil, flavonoids, lecithin, alfalfa, CoQ10 with resveratrol, glucosamine, and a herbal immune supplement. The majority of women also took evening primrose oil and probiotic and men took zinc, garlic, saw palmetto and a protein soy supplement. A greater degree of supplement use was associated with more favourable concentrations of serum homocysteine, C-reactive protein, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides as well as lower risk of prevalent elevated blood pressure and diabetes even when confounders were controlled, such as education, income, BMI.46 Another study on 8555 women from the US Nurses Health study showed that regular use of multivitamin supplements may decrease the risk of ovulatory infertility.47

Farvid et. al.48 randomised 69 people with type 2 diabetes to 4 groups to receive 1 of the following daily supplements for 3 months: Group 1 200mg Mg, 30mg Zn; Group 2 200mg vitamin C and 100IU vitamin E; Group 3 minerals plus vitamins; Group 4: placebo. After 3 months Group 2 (vitamins) and Group 3 (vitamins and minerals) had improved glomerular (but not tubular) kidney function with reduced excretion of urinary albumin. Group 3 experienced additional benefits: reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting serum glucose and malondialdehyde concentration, increases in HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein A1 levels. This study not only supports the use of multivitamins in diabetes but suggests a synergistic action of vitamin and mineral therapy with the combination achieving better results than vitamins or minerals alone.

Harvard University Healthy Eating Pyramid

Nutrition scientists at Harvard University School of Public Health developed their own version of a Healthy Eating Pyramid in 200649 based upon the best available scientific evidence linking diet and health independent of businesses and organisations with vested interests (see Figure 2.4). The Harvard University experts agreed that there was enough evidence to recommend a multivitamin daily (which appears alongside their pyramid). However, some scientists believe there is not enough scientific evidence to recommend either for or against taking a daily multivitamin.50 The Harvard scientists argue this is a short-sighted point of view49 since it may never be possible to conduct randomised trials that are long enough to test the effects of multiple vitamins on risks of cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, and other degenerative conditions. They conclude that, balancing the weight of all of the evidence — from epidemiological studies on diet and health, to biochemical studies on the minute mechanisms of disease — the potential health benefits of taking a standard daily multivitamin far outweigh the potential risks.51

Prescribing micronutrient supplements

How can micronutrients be of help?

Table 2.6 Circumstances that place patients at risk of nutrient deficiency and suggested supplementation

| Food habits | Consider short-term (or long-term if food habits cannot be altered) low-dose supplementation with:∗ |

|---|---|

| At risk individuals (see Table 2.1), especially patients following reduced energy diets (<1500kcal/day) for several months, elderly, polypharmacy, GI disorders | Multivitamin, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, B complex, fibre |

| Not eating recommended number of food serves (but if eating vegemite will not need B complex) (see Table 2.4) | Multivitamin, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, B complex, fibre |

| High intake of sugar, refined carbohydrates/white flour, processed foods, pre-cooked meals, take away food | Multivitamin, Mg, Chromium, Zn, fibre |

| Excess alcohol | Multivitamin, Ca, Mg, K, Fe, Zn, Se, folate, thiamin and other B vitamins, vit C/D/E |

| Eating out more than twice a week for dinner, especially at fast food restaurants | Multivitamin, fibre |

| Fatty fish consumed less than 3 times a week | Omega-3 EPA/DHA |

| Low intake of animal foods (if 2 brazil nuts consumed daily Se intake adequate; if vegemite or bananas/walnuts/pecans/potatoes consumed daily then B6 may be adequate) | Fe, Zn, Se, B12, B6 |

| Total avoidance of animal foods and fish (vegan diet) | B12, Iodine, Fe, Zn, Ca, omega-3, vit D, vitamin A (some medical conditions affect conversion of beta carotene from plant foods to vitamin A) |

| Low intake of dairy or calcium fortified soy foods (<3 serves/day) For food cultures that do not habitually consume milk products, a low intake of certain soup broths (soups made form bones can be high in calcium, especially if acid ingredients such as vinegar or lemon are used, which facilitate dissolution of bones), prawns, fish with soft bones, tofu Chinese cabbage, broccoli, and bok choy may suggest inadequate calcium intake) | Ca, B2 |

| Low intake of dairy, eggs, carrots, sweet potato, dark green leafy vegetables and avoidance of organ meats (e.g. liver) | Vitamin A |

| Reduced carbohydrate diets or low intake of wholegrain cereals/breakfast cereals (<3 serves/day), not compensated by adequate meat, fish, legumes, nuts | B1, Mg, Zn, Cr |

| Low intake of fish/seaweed (less than once a week), iodised bread, or use of un-iodised salt or un-iodised milo or multivitamin not containing iodine (especially important for pregnant/lactating women and children) | Iodine |

| Low intake of dark green leafy vegetables (<3 times a week) e.g. spinach, endives, kale, chickory, Chinese greens, nuts (<3 times a week), wholegrain cereals/breakfast cereals (<3 serves/day), legumes (<once a week) | Mg, Zn, folate, fibre |

| Low intake of fruit and vegetables | Vit C, folate, b carotene, Mg, fibre |

| Low intake of flax seeds, chia seeds, canola/soybean oil or spreads, walnuts, pumpkin seeds, tofu | Omega-3 linolenic |

| Low intake of unsaturated oils/spreads (<1 tbs/day) and nuts/seeds (whole/spread) or fatty fruit (avocado) or sweet potato |

Note: use this table in conjunction with Appendix 1 ‘Food sources of macronutrients, micronutrients, phytonutrients and chemicals’.

∗ Ideally, it is best to do blood/urine tests to check levels before supplementation is commenced but this may not be possible for some nutrients (because they may not be covered by public medical system or tests may not accurately measure nutrient levels in body). In this situation supplementation (with fortified drinks or capsules) should be low dose, around the RDI levels or below the upper tolerable level (Table 2.4). However, if blood/urine tests show deficiency, a much higher dose above the RDI will be needed.

(source: www.healthyeatingclub.com)

Table 2.7 Some conditions(s) that may be prevented or improved with nutrient administration

| Conditions | Supplementation |

|---|---|

| Prevention of neural tube defects in ongoing pregnancies53, 54, 55 | B12, folate |

| Mood disturbance/insomnia,56 depression, affective disorder57, 58 Psychiatric disorders58 |

Note: For more detail see chapters in this book regarding specific conditions.

When a plant is looking unwell, amongst other ways, we improve the quality of the soil by changing the soil (analogous to improving the food source) and adding fertiliser rich in micronutrients. We can use this concept as an analogy for improving human health.

What if a patient presents with vague symptoms such as ‘tiredness’ and their dietary history reveals that their diet could be improved although a specific vitamin deficiency cannot be identified? What if the clinician feels they do not have time to provide dietary counselling and the patient can’t afford a dietitian? Is it acceptable to use a multivitamin supplement or fortified protein drink instead of, or in addition to, dietary counselling? The answer is yes but the clinician ought to solve the problem with food as often as possible. Some patients may need long-term supplementation if they are unable to improve their diet or if they have certain conditions or take certain medications.11

Cautions when prescribing supplements

One must be cautious when prescribing nutrients, especially in the presence of kidney and/or liver disease. In most cases, there are minimal side-effects. Table 2.4 provides upper safe levels for each nutrient.

Vitamin E

The adult safe upper intake level (UL) for vitamin E is set at 400IU/300mg daily. Vitamin E has a blood thinning effect. In 1 study of 28 519 men, vitamin E supplementation at the low dose of about 50IU synthetic vitamin E per day caused an increase in fatal hemorrhagic strokes.52 Based on its blood thinning effects, there are concerns that vitamin E could cause problems if it is combined with blood thinning medications, such as warfarin (Coumadin), heparin, clopidogrel (Plavix), ticlopidine (Ticlid), pentoxifylline (Trental), and aspirin. However, a study has shown that Vitamin E does not interfere with the anticoagulation response of warfarin.166

A study that evaluated vitamin E plus aspirin did in fact find an additive effect.167 There is also at least a remote possibility that vitamin E could also interact with supplements that possess a mild blood thinning effect, such as garlic, policosanol, and ginkgo. Individuals with bleeding disorders, such as haemophilia, and those about to undergo surgery or labour and delivery should also approach vitamin E with caution. In addition, vitamin E might temporarily enhance the body’s sensitivity to its own insulin in individuals with type 2 diabetes168 but may raise blood pressure in people with diabetes.169 Some evidence suggests that long-term usage of vitamin E at high doses (>400IU/day) might increase overall death rate, for reasons that are unclear.170 Vitamin E may help to prevent heart disease in people with diabetes.171 A number of these studies have used synthetic vitamin E and this may explain differences in safety between the studies. Also, ideally vitamin E should be given with vitamin C in order to allow vitamin E to function most effectively.172

Folate

The US Institute of Medicine173 recommends against obtaining more than 1000mg per day of folic acid from supplements or fortified food; folate intake from food is not a concern.174 Excess folic acid supplementation can mask the signs of a vitamin B12 deficiency (up to 1 in 6 older people either don’t get enough vitamin B12 or don’t absorb it efficiently). Too much folic acid can hide the signs of anaemia, an early warning of a vitamin B12 deficiency. This could allow the problem to progress to the point of causing confusion, dementia, and/or severe and irreversible damage to the nervous system. There is some concern that too much folic acid can accelerate the growth of existing tumours and may increase the risk for colorectal, breast175 and prostate cancer.176 It is thought that folate can protect against colorectal cancer if commenced earlier in life.177 Although these studies are limited, and other, similar studies have shown no association between folic acid and increased cancer risk, they sound a warning about consuming too much folic acid supplementation that deserves further investigation.

Vitamin C

The safe tolerable upper intake level for vitamin C from supplements and diet is 2000mg. Even within the safe intake range for vitamin C, some individuals may develop diarrhoea and abdominal discomfort which resolves on dose reduction. Long-term high dose vitamin C intake has not been linked with kidney stone formation but there may be certain individuals who are particularly at risk for vitamin C-induced kidney stones.178 People with a history of kidney stones and those with kidney failure and who have a defect in vitamin C or oxalate metabolism should probably restrict vitamin C intake to approximately 100mg daily. High-dose vitamin C should also be avoided in glucose-6–phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, iron overload, or a history of intestinal surgery.

Weak evidence suggests that vitamin C, when taken in high doses, might reduce the blood thinning effects of warfarin (Coumadin) and heparin. Heated disagreement exists regarding whether it is safe or appropriate to combine antioxidants such as vitamin C with standard chemotherapy drugs. The reasoning behind the concern is that some chemotherapy drugs may work in part by creating free radicals that destroy cancer cells, and antioxidants might interfere with this beneficial effect. However, there is no good evidence that antioxidants actually interfere with chemotherapy drugs, but there is growing evidence that they do not.179

However, new research on stem cells suggests that high (but not low) doses of antioxidants such as vitamins C and E can increase DNA damage, increasing potentially the risk of developing cancer.180

Vitamin A, β−carotene

Nutrient toxicity, especially with prolonged use, is a concern. Most supplements in Australia have warnings of this on their labels. For instance, signs of vitamin A toxicity include skin dryness. Vitamin A supplementation in excess of 2500IU per day in pregnant women is associated with fetal teratogenicity.181 Beta–carotene is a safer form of vitamin A. However, beta–carotene in high doses should be avoided in smokers and asbestos-related lung disease as it may increase the risk of lung cancer in these situations.182 This study has been criticised because synthetic β-carotene rather than the natural form was used.

Zinc

The safe tolerable upper intake level for zinc from supplements and diet is 40mg. Long-term use of oral zinc at dosages of 100mg or more daily can cause a number of toxic effects, including severe copper deficiency and reduced iron absorption leading to anaemia, impaired immunity and heart problems. Zinc at a dose of more than 50mg daily might reduce levels of HDL cholesterol. In addition, very weak evidence hints that use of zinc supplements might increase risk of prostate cancer in men.183

Magnesium

The safe tolerable upper intake level for magnesium from supplements is 350mg. This level of daily supplemental magnesium intake is not likely to pose a risk of diarrhoea or gastrointestinal disturbance in almost all individuals. The initial symptom of excess magnesium supplementation is diarrhoea — a well-known side-effect of magnesium that is used therapeutically as a laxative. Individuals with impaired kidney function are at higher risk for adverse effects of magnesium supplementation, and symptoms of magnesium toxicity have occurred in people with impaired kidney function taking moderate doses of magnesium-containing laxatives or antacids. Elevated serum levels of magnesium (hypermagnesemia) may result in a fall in blood pressure (hypotension). Some of the later effects of magnesium toxicity, such as lethargy, confusion, disturbances in normal cardiac rhythm, and deterioration of kidney function, are related to severe hypotension. As hypermagnesemia progresses, muscle weakness and difficulty breathing may occur. Severe hypermagnesemia may result in cardiac arrest. However, there are some conditions that may warrant higher doses of magnesium under medical supervision.184

Chromium

The tolerable upper intake level for chromium is 300μg/day. There is some evidence that if chromium is taken in high enough amounts, it may be converted from its original safe form (chromium 3) into a known carcinogen, chromium 6.185 The risk of chromium toxicity (kidney, liver, bone marrow damage) is believed to be higher in individuals who already have liver or kidney disease. There are also several concerns about the picolinate form of chromium in particular. Picolinate can alter levels of neurotransmitters. This has led to concern among some experts that chromium picolinate might be harmful for individuals with depression, bipolar disease, or schizophrenia. Finally, there are also concerns, still fairly theoretical and uncertain, that chromium picolinate could cause adverse effects on DNA.186

Iodine

The tolerable upper intake level for iodine is 1100mcg/day. The World Health Organization warns iodine deficiency is widespread and contributing to worldwide health problems. Iodine deficiency is commonly found in Western countries and populations regarded as iodine sufficient. This emerging deficiency is due to a number of factors including depletion in soils, farmed fish and low intake of iodised salt. For instance, recent studies demonstrate almost half of all Australian primary school children are mild to moderately iodine deficient.187

Consequently, the Foods Standard Australia New Zealand now recommend Australians use iodised salt. Iodine is necessary for the synthesis of thyroid hormones. Consequently, severe iodine deficiency can result in hypothyroidism, goitre and cretinism. Borderline iodine deficiency may give rise to clinical symptoms of hypothyroidism without deranged thyroid hormone values, and give rise to sub-clinical thyroid dysfunction leading to health problems resembling hypothyroidism or diseases that have been associated with the occurrence of hypothyroidism such as obesity in adults and children, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), psychiatric disorders, fibromyalgia, neuropsychological consequences such as mental and growth retardation, learning difficulties, and possibly malignancies.188

Most food sources of iodine include seafood, iodised bread, iodised milo and iodised salt. The Japanese diet is high in kelp and seaweed which may also be an important factor contributing to low body weight in the Japanese population. Iodine deficiency (or borderline deficiency) may be a factor contributing to weight gain of some populations. According to US researchers, many prenatal multivitamins did not contain the recommended daily dose of iodine crucial for normal fetal neurocognitive development.189

Conclusion

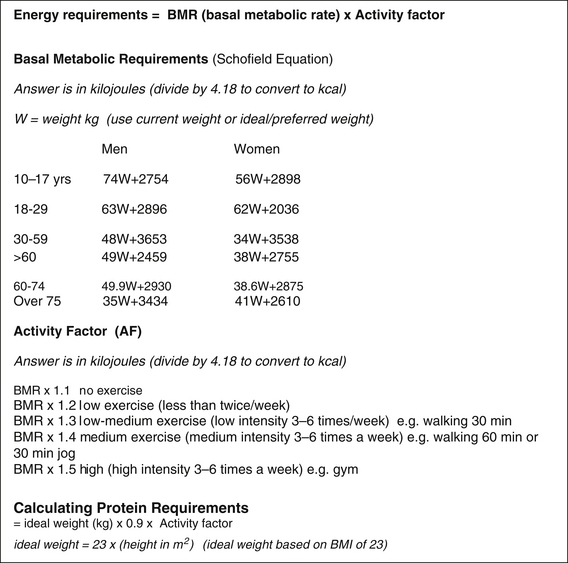

Nutrition depends not only on food consumption but on energy expenditures associated with basal metabolic rate, the amount of physical activity performed, body composition, and metabolic conditions. Also there exists significant nutritional differences between individuals, age groups, lifestyles, lifecycles (pregnancy and lactation) and under different food consumption conditions. The nutrition–health relationship is primarily dependant on the capacity a human being has to adapt to and maintain metabolic balance throughout life. This adjustment is easier the more that the food consumed agrees with the functional capacity of the genetic profile and the interaction between nutrients–genes and the environment.190 The greater the efficiency of the system the better the health achieved over longer periods of time.

Nutritional assessments have an important role to play in lifestyle interventions for preventing disease and in chronic disease management. This is especially so in the elderly population, for example, where nutritional options that include micronutrient supplementations provide additional beneficial options, especially as the aged are particularly prone to inadequate nutritional status because of factors such as age-related physiological and social changes, occurrence of chronic diseases, use of medications, and decreased mobility.

1 Wahlqvist M.L., Strauss B. Clinical Nutrition in primary health care. Australian Family Physician. 1992;21:1485-1492.

2 Kyle U.G., Unger P., Dupertuis Y.M., et al. Body composition in 995 acutely ill or chronically ill patients at hospital admission: a controlled population study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(7):944-955.

3 Sydney-Smith J. Nutritional Assessment. J Comp Med. 2006:28-40.

4 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004–2005 National Health Survey. Summary of results. Report No. 4364.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006. Online. Available: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/3B1917236618A042CA25711F00185526/$File/43640_2004–05.pdf (accessed January 2009)

5 Larsen K., Ryan C., Abraham A.B. The Secure and Sustainable Food Systems for Victoria, Victorian Eco-Innovation Lab (VEIL), Research Report no 1. University of Melbourne; April 2008. Online. Available: http://www.scribd.com/doc/6539650/Sustainable-and-Secure-Food-Systems-for-Victoria (accessed January 2009)

6 Burns K., Sacks G., Gold L. Longitudinal study of Consumer Price Index (CPI) trends in core and non-core foods in Australia. ANZ J Pub Health. 2008;32(5):450-453.

7 Markovic T., Natoli S. Paradoxical nutrient deficiency in overweight and obesity: the importance of nutrient density. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009;190:149-151.

8 Public Health Association Australia. A Future for Food: Addressing public health, sustainability and equity from paddock to plate. Online. Available: http://www.phaa.net.au/futureforfood.php (accessed Feb 2009).

9 CSIRO and The University of South Australia. 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Department of Health and Ageing. 2008.

10 Fletcher R.H., Fairfield K.M. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(23):3116-3126. 3127–9

11 Wahlqvist M., Kouris-Blazos A.. Nutrition — is diet enough. J Comp Med. 2002;3:1. Nov-Dec; 46–8

12 Rutishauser I. Nutritional Assessment and Monitoring. In: Food and Nutrition. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2002.

13 Heimburger D.C., Ard J.D. Handbook of Clinical Nutrition, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.

14 Corrada M.M., Kawas C.H., Mozaffar F., et al. Association of body mass index and weight change with all-cause mortality in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(10):938-949.

15 Lee C.D., Blair S.N., Jackson A.S. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. AJCN. 1999;69(3):373-380.

16 Kouris-Blazos A. Morbidity Mortality paradox of 1st generation Greek Australians. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002;11:S569-S575.

17 de Castro J.M. The time of day of food intake influences overall intake in humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:104-111.

18 Adapted from Kouris-Blazos A & Wahlqvist ML. HEC Healthy Eating Pyramid. 2001. Online. Available: www.healthyeatingclub.com (accessed Sept 2009)

19 Abbott Glucerna. Online. Available: http://glucerna.com./smart_nutrition/npwd.aspx (accessed Sept 2009).

20 Kouris-Blazos A. Dietary advice and food guidance systems. In: Food and Nutrition. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2002:532-557.

21 Trichopoulou A., Kouris-Blazos A., Wahlqvist M.L., et al. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ. 1995;311:1457-1460.

22 Darmadi-Blackberry I., Wahlqvist M.L., Kouris-Blazos A., et al. Legumes: the most important dietary predictor of survival in older people of different ethnicities. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(2):217-220.

23 Sofi F., Cesari F., Abbate R., et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344

24 Hu F.B. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3-9.

25 Martínez-González M.A., de la Fuente-Arrillaga C., Nunez-Cordoba J.M., et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:1348-1351.

26 Benetou V., Trichopoulou A., Orfanos P., et al. Greek EPIC cohort. Conformity to traditional Mediterranean diet and cancer incidence: the Greek EPIC cohort. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(1):191-195.

27 Harriss L.R., English D.R., Powles J., et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular mortality in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. AJCN. 2007;86(1):221-229.

28 Shai I., Schwarzfuchs D., Henkin Y., et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. NEJM. 2008;359:229-241.

29 For an online version of this pyramid go to www.thenutritionsource.org or http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/.

30 Mayer A.M. Historical changes in the mineral content of fruits and vegetables. Br Food J. 1997;99(6):207-211.

31 White P.J., Broadley M.R. Historical variation in the mineral composition of edible horticultural products. J Hort Sci and Biotech. 2005;80:660-667.

32 Davis D.R., Epp M.D., Riordan H.D. Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops 1950 to 1999. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:669-682.

33 Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Health and Medical Research Council and Ministry of Health New Zealand. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand, Including Recommended Dietary Intakes. Commonwealth of Australia. 2006. Online. Available: www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications (accessed Sept 2007)

34 Heimburger D.C., Ard J.D. Handbook of Clinical Nutrition, 4th edn. Mosby Elsevier; 2006.

35 Helman A.D. Vitamins, Mineral and Other Nutrients in Clinical Practice. a GP Guide Arbor Communications P/L Vic. 1991.

36 Andrew A., et al. Effect of B-vitamin therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy: a randomised control trial. JAMA. 2010;303(16):1603-1609.

37 Ebbing M., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and B12. JAMA. 2009;302:2119-2126.

38 Pentti, et al. Use of calcium supplements and risk of coronary heart disease. Maturitas. 2009;63(1):73-78.

39 National Health and Medical Research Council. Recommended dietary intakes. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service (AGPS); 1989.

40 Dept Community Services and Health. National dietary survey of adults: 1983. No. 2: dietary intakes. Canberra: AGPS; 1987.

41 Dept Community Services and Health. National dietary survey of schoolchildren (aged 10–15 years): 1985. No. 2: dietary intakes. Canberra: AGPS; 1989.

42 Martinez J.A., Parra M.D., Santos J.L., et al. Genotype-dependent response to energy-restricted diets in obese subjects: towards personalized nutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(Suppl 1):119-122.

43 Helman AD. Vitamins, Minerals and other Nutrients in Clinical Practice, a GP guide. Arbor Communications Pty Ltd, ISBN:0 646 07837.

44 Bjelakovic G., Nikolova D., Gluud L.L., et al. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2008;April 16(2):7176.

45 Herchberg S., Galan P., Preziosi P., et al. The SU.VI.MAX Study: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the health effects of antioxidant vitamins and minerals. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(21):2335-2342.

46 Block G., Jensen C.D., Norkus E.P., et al. Usage patterns, health and nutritional status of long-term multiple dietary supplement users: a cross-sectional study. Nutrition Journal. 2007;6:30.

47 Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Rosner B.A., et al. Use of multivitamins, intake of B vitamins and risk of ovulatory infertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:668-676.

48 Farvid M.S., Jalali M., Siassi F., et al. Comparison of the effects of vitamins and/or mineral supplementation on glomerular and tubular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2458-2464.

49 Online. Available: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/multivitamin/index.html. Updated in 2008 (accessed Jan 2009).

50 National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. multivitamin/mineral supplements and chronic disease prevention. AJCN. 2007;85:257S-264S.

51 Ames B.N., McCann J.C., Stampfer M.J., et al. Evidence-based decision making on micronutrients and chronic disease: long-term randomized controlled trials are not enough. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:522-523. (author reply 523–4)

52 Leppala J.M., Virtamo J., Fogelholm R., et al. Controlled trial of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplements on stroke incidence and mortality in male smokers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:230-235.

53 Kirke P.N., Molloy A.M., Daly L.E., et al. Materal plasma folate and vitamin B12 are independent risk factors for NTDs. Quar J Med. 1993;86:703-708.

54 Wolff T., Witkop C.T., Miller T., et al. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid supplementation for the prevention of neural tube defects: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Internal Medicine. 2009 May 5;150(9):632-639.

55 Molloy A.M., Kirke P.N., Troendle J.F., et al. Maternal vitamin B12 status and risk of neural tube defects in a population with high neural tube defect prevalence and no folic Acid fortification. Pediatrics. 2009 Mar;123(3):917-923.

56 Benton D., Haller J., Fordy J. Vitamin supplementation for 1 year improves mood. Neuropsychobiology. 1995;32:98-105.

57 Benkelfat C., Ellenbogen M.A., Dean P., et al. Mood-lowering effects of Trytophan depletion: enhanced susceptibility in young men at genetic risk for major affective disorder. Arch Gen Psych. 1994:687-697.

58 Hofle K.H. Magnesium in psychotherapy. Magn Res. 1988;1:99.

59 Keli S.O., Hertog M.G.L., Feskens E.J.M., et al. Dietary flavinoids, antioxidants vitamins and the incidence of stroke. The Zulphen Study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:637-642.

60 Hopkins P.N., Wu L.L., Wu J., et al. Higher plasma homocysteine and increased susceptibility to adverse effects of low folate in early familial coronary artery disease. Arteriosc Throm Vas Biol. 1995;15:1314-1320.

61 Abbey M. The importance of vitamin E in reducing cardiovascular risk. Nutrition Reviews. 1995;53(9):S28-S32.

62 Verlarigieri A.J., Bush M.J. Effects of d-a-Tocopherol Supplementation on experimentally induced primate atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 1992;11:131-138.

63 Cordova C., Musca A., Viola F., et al. Influence of ascorbic acid on platelet aggregation in vitro and in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 1981;41:15-19.

64 Bordia A., Paliwol D.K., Jain K., et al. Acute effect of ascorbic acid on fibronylitic activity. Atherosclerosis. 1978;30:351-354.

65 Stampfer M.J., Hennekens C.H., Manson J.E., et al. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary disease in women. NEJM. 1993;328:1444-1449.

66 Rimm E.B., Stampfer M.J., Ascherio A., et al. Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary disease in men. NEJM. 1993;328:1450-1456.

67 Kritchevsky S.B., Shimakawa T., Tell G.S., et al. Dietary antioxidants and carotid artery wall thickness. Circulation. 1995;92:2142-2150.

68 Stephens N.G., Parsons A., Schofield P.M., et al. Randomised trial of vitamin E in patients with coronary disease: Cambridge Heart Antioxidant Study (CHAOS). Lancet. 1996;347:781-786.

69 Baum M.K., Shor-Posner G., Lu Y., et al. Micronutrients and HIV-1 disease progression. AIDS. 1995;9:1051-1056.

70 Odeh M. The role of zinc in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. J Int Med. 1992;231:463-469.

71 Flagg E.W., Coates R.J., Greenberg R.S. Epidemiologic studies of antioxidants and cancer in humans. J Am Coll Nutr. 1995;14(5):419-427.

72 Alberg A.J., Selhub J., Shah K.V., et al. The risk of cervical cancer in relation to serum concentrations of folate, vitamin B12, and Homocysteine. Can Epidem Biomark Prevent. 2000;9:761-764.

73 Hansson L.E., Nyren O., Bergstrom R., et al. Nutrients and gastric cancer risk. A population-based case-control study in Sweden Int J Cancer. 1994;57:638-644.

74 Bjelakovic G., Nikolova D., Simonetti R.G., et al. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of gastrointestinal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004 Oct 2–8;364(9441):1219-1228.

75 Theodoratou E., Farrington S.M., Tenesa A., et al. Dietary vitamin B6 intake and the risk of colorectal cancer. Can Epidem Biomark Prevent. 2008;17(1):171-182.

76 Saito M., Kato H., Tsuchida T., et al. Chemoprevention effects on bronchial squamous metaplasia by folate and vitamin B12 in heavy smokers. Chest. 1994;102(2):496-499.

77 Hemila H. Does Vitamin C alleviate the symptoms of the common cold? Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:1-6.

78 Mossad S.B., Macknin M.L., Medendorp S.V., et al. Zinc gluconate lozenges for treating the common cold. A randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Int Med. 1996;125(2):81-88.

79 Hunt C. The clinical effects of vitamin C supplementation in elderly hospitalised patients with acute respiratory infection. Int J Vit Nut Res. 1994;64:212-219.

80 Prasad A.S., Beck F.W.J., Bao B., et al. Duration and severity of symptoms and levels of Plasma Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist, Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor, and Adhesion Molecules in patients with common cold treated with zinc acetate. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(6):795-802.

81 Keen H. Treatment of diabetic neuropathy with gamma-linolenic acid. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):8-15.

82 Paolisso G., Balbi V., Volpe C., et al. Metabolic benefits deriving from chronic vitamin C supplementation in aged non-insulin dependent diabetics. J Am Coll Nut. 1995;14(4):387-392.

83 Thompson K.H., Godin D.V. Micronutrients and antioxidants in the progression of diabetes (Review). Nutr Res. 1995;15(9):1377-1410.

84 Wilson B.E., Gondy A. Effects of chromium supplementation on fasting insulin levels and lipid parameters in healthy, non-obese young subjects. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 1995;28:179-184.

85 Jamal G.A. The use of gamma-linolenic acid in the prevention and treatment of diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 1994;11(2):145-149.

86 Norris J.M., Yin X., Lamb M.M., et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2007;298(12):1420-1428.

87 Yaqub B.A., Siddique A., Sulimani R. Effects of Methylcobalamin on Diabetic Neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;94:105-111.

88 Biagi P.L., Bordoni A., Hrelia S., et al. The effect of gamma-linolenic acid on clinical status, red cell fatty acid composition and membrane microviscosity in infants with atopic dermatitis. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1994;20(2):77-84.

89 Fiocchi A., Sala M., Signoroni P., et al. The efficacy and safety of gamma-linolenic acid in the treatment of infantile atopic dermatitis. J Int Med Res. 1994;22(1):24-32.

90 Ginter E. Pretreatment serum-cholesterol and response to ascorbic acid. Lancet. 1979;2(8149):958-959.

91 Jain A.K., Vargas R., Gotzkowsky S., et al. Can Garlic Reduce Levels of Serum Lipids? A Controlled Clinical Study. Amer J Med. 1993;94:632-634.

92 Warshafsky S., Kamer R.S., Sivak S.L. Effect of garlic on total serum cholesterol-A meta-analysis. Ann Inter Med. 1993;119:599-605.

93 Rosales F.J. Vitamin A supplementation of vitamin A deficient measles patients lowers the risk of measles-related pneumonia in zambian children. J Nutr. 2002;132(12):3700-3703.

94 Frieden T.R., Sowell A.L., Henning K.J., et al. Vitamin A levels and severity of measles: New York City. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:182-186.

95 Olivieri O., Girelli D., Stanzial A.M., et al. Selenium, zinc and thyroid hormones in healthy subjects: low T3/T4 ratio in the elderly is related to impaired selenium status. Bio Trac Ele Res. 1996;51:31-42.

96 Barrington J.W., Lindsay P., James D., et al. Selenium deficiency and miscarriage: a possible link. Br.J Obst Gyn. 1996;103:130-132.

97 Singh R.B., Niaz M.A., Rastogi S.S., et al. Usefulness of antioxidant vitamins in suspected acute myocardial infarction (the Indian experiment of infarct survival-3). Amer J Cardiol. 1996;77:232-236.

98 BrodskyMagnesium M.A., Myocardial Infarction, Arrhythmias. J. Am Coll Nut. 1992;11(5):607.

99 Millane T.A., Camm A.J. Magnesium and the Myocardium. Br Heart J. 1992;68:441-442.

100 Thogerson A., Johnson O., Wester P.O. Effects of intravenous magnesium sulfate in suspected acute myocardial infarction on acute arrythmias and long-term outcome. Int J Cardiol. 1995;49:143-151.

101 Hampton E.M., Whang D.D., Whang R. Intravenous magnesium therapy in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Pharmocoth. 1994;28:212-219.

102 Gaziano J.M., Manson J.E., Ridker P.M., et al. Beta-carotene therapy for chronic stable angina. Circulation. 1990;82(Suppl. 111):111-201. abstract

103 Rapola J.M., Virtamo J., Haukka J.K., et al. Effect of vitamin E and betacarotene on the incidence of angina pectoris. A randomised, double blind, controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275:693-698.

104 Lehr D. The Possible beneficial effect of selenium administration in antiarrhythmic therapy. J Am Coll Nutri. 1994;13(5):496-498.

105 Crestanello J.A., Doliba N.M., Doliba N.M., et al. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on mitochondrial function after myocardial ischemia reperfusion. J Surg Res. 2002;102(2):221-228.

106 Dolske M.C., Spollen J., McKay S. A preliminary trial of ascorbic acid as supplemental therapy for autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1993;17(5):765-774.

107 Martineau J., Barthelemy C., Roux S., et al. Electrophysiological effects of fenfluramine or combined vitamin b6 and magnesium on children with autistic behaviour. Develop Med Child Neurol. 1989;31:721-727.

108 Adler L.A., Peselow E., Rotrosen J., et. al. Vitamin E Treatment of Tardive Dyskinesia. Am J Psych. 1993;150(9):1405-1407.

109 England M.R., Gordon G., Salem M., et al. Magnesium Administration and Dysrhythmias After Cardiac Surgery: A Placebo-controlled, Double-Blind, Radomized Trial. JAMA. 1992;268:2395-2402.

110 Shepherd J., Jones J., Frampton G.K., et al. Intravenous magnesium sulphate and sotalol for prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(28):1-118.

111 Vutyavanich T., Wongtrangan S., Ruangsri R. Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:881-884.

112 Czeizel A.E., Dudas F.G., et al. The effect of periconceptional multivitamin-mineral supplementation on vertigo, nausea and vomitting in the first trimester of pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1992;251:181-185.

113 Argyriou A.A., Chroni E., Koutras A., et al. Vitamin E for prophylaxis against chemotherapy-induced neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2005;64:26-31.

114 Shults C.W., Oakes D., Kieburtz K., et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: evidence of slowing of the functional decline. Archives of Neurology. 2002;59:1541-1550.

115 Shults C.W., et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: evidence of slowing of the functional decline. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1541-1550.

116 Lamm D., Riggs D.R., Shriver J.S., et al. Megadose vitamins in bladder cancer: a double-blind clinical trial. J Urol. 1994;141:21-26.

117 Dawson E.B., Harris W.A., Teter M.C., et al. Effect of ascorbic acid supplementation on the sperm quality of smokers. Fertility and Sterility. 1992;58:1034-1039.

118 Heseker H., Schneider R. Requirement and supply of Vitamin C, E and betacarotene for elderly men and women. Eur J Cli Nut. 1994;13:57-61.

119 Roebothan B.V., Chandra R.K. Relationship between nutritional status and immune function of elderly people. Age and Ageing. 1994;23:49-53.

120 Woo J., Ho Sc, et al. Nutritional status of elderly patients during recovery from chest infection and the role of nutritional supplementation assessed by a prospective randomised single blind trial. Age and Ageing. 1994;23:40-48.

121 West S., Vitale S., Hallfrisch J., et al. Are antioxidants or supplements protective for age related macular degeneration? Arch Opthalmol. 1994;112:222-227.

122 Schanlin-Karrila M., Mattila L., Jansen C.T., et al. Evening primrose oil in the treatment of atopic eczema: effect on clinical status, plasma phospholipid fatty acids and circulating blood prostaglandins. B J Dermatol. 1987;117:11-19.

123 Scholl T.O., Hediger M.L., Schall J.L., et al. Low zinc intake during pregnancy: its association with preterm and very preterm delivery. Am J Epid. 1993;137:1115-1123.

124 Simmer K., Lort-Phillips L., James C., et al. A double-blind trial of zinc supplementation in pregnancy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45:139-144.

125 Apgar J. Zinc and reproduction: an update. J Nutr Biochem. 1992;3:266-277.

126 Castilloduran C., Garcia H., Venegas P., et al. Zinc supplementation increases growth velocity of male children and adolescents with short stature. Acta Paediatrica. 1994;83:833-837.

127 Schectman G., Byrd J.C., Hoffmann R. Ascorbic acid requirements for smokers: analysis of a population survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:1466-1470.

128 Hunt J.R., Gallagher S.K., Johnson L.K. Effect of ascorbic acid on apparent iron absorption by women with low iron stores. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:1381-1385.

129 Wei Q., Matanoski G., et al. Vitamin supplementation and reduced risk of basal cell carcinoma. J Clin Epidem. 1994;47:829-836.

130 Abraham G.E., Glechas J.D. Management of fibromyalgia: rationale for the use of magnesium and malic acid. J Nut Med. 1992;3:49-59.

131 Digiesi V., Cantini F., Oradei A., et al. coenzyme Q10 in essential hypertension. Mol Aspects Med. 1994;15:s257-s263.

132 Shibutani Y., Sakamoto K., Katsuno S., et al. Relation of serum and erythrocyte magnesium levels to blood pressure and a family history of hypertension. ACTA Paeditr Scand. 1990;79:316-321.

133 Champagne C.M. Magnesium in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions: a review. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(2):142-151.

134 Appel L.J., Miller E.R.III, Seidler A.J., et al. Does supplementation of diet with ‘fish oil’ reduce blood pressure? A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1429-1438.

135 Silagy C., Neil A. A meta-analysis of the effect of garlic on blood pressure. J Hypertension. 1994:463-468.

136 Witteman J.C.M., Grobbee D.E., Derk F.H.M., et al. Reduction of blood pressure with oral magnesium supplementation in women with mild to moderate hypertension. Am Clin Nutr. 1994;60:129-135.

137 Bucher H.C., Guyatt G.H., Cook R.J. Effect of calcium supplementation on pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1996;275:1113-1117.

138 Gateley C.A., Miers M., Mansel R.E., et al. Drug treatments for mastalgia: 17 years experience in the Cardiff Mastalgia Clinic. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(1):12-15.

139 Jackson C., Gaugris S., Sen S.S., Hosking D. The effect of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) on the risk of fall and fracture: a meta-analysis. QJM. 2007;100(4):185-192.

140 Chapuy M.C., Arlot M.E., Duboeuf F., et al. Vitamin D and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderley women. NEJM. 1992;327(23):1637-1642.

141 Sojka J.E. Magnesium supplementation and osteoporosis. Nutr Rev. 1995;53:71-74.

142 Kaminski M., Boal R. An effect of ascorbic acid on delayed-onset muscle soreness. Pain. 1992;50:317-321.

143 Semba Richard D., et al. Abnormal T-Cell subset proportions in vitamin-a deficient children. Lancet. 1993 Jan 2;341:5-8.

144 Chandra R.K. Effect of vitamin and trace element supplementation on immune responses and infection in elderly subjects. Lancet. 1992;340:1124-1127.

145 Brosche T., Platt D. On the Immunomodulatory action of garlic (Allium sativum L.). Medizinische Welt. 1993;44:309-313.

146 Hatch G.E. Asthma, inhaled oxidants and dietary antioxidants. Amer J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:625S-630S.

147 Bielory L., Rinki G. Asthma and vitamin C. Ann Aller. 1994;73:89-96.

148 Sydow M., Crozier T.A., Zielmann S., et al. High-dose intravenous magnesium sulfate in the management of life-threatening Status Asthmaticus. Intens Care Med. 1993;19:467-471.

149 Attias J., Weisz G., Almog S., et al. Oral magnesium intake reduces permanent hearing loss by noise exposure. Amer J Otolaryng. 1994;15:26-32.

150 Shemesh Z., Attias J., Ornan M., et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with chronic tinnitus and noise-induced hearing loss. Amer J Otolaryng. 1993;14(2):94-99.

151 Munger K.L., Zhang S.M., O’Reilly E., et al. Vitamin D intake and incidence of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(1):60-65.

152 Landon R.A., Young E.A. Role of magnesium in regulation of lung function. J Amer Diet Assoc. 1993;93(6):674-677.

153 Abu-Osba Y.K., Galal O., Manasra K., et al. Treatment of severe persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn with magnesium sulfate. Arch of Dis in Child. 1992;67:31-35.

154 Sibai B.M. Magnesium sulfate is the ideal anticonvulsant in preeclampsia. Am J Obst Gyn. 1990;162:1141-1145.

155 Hankinson S.E., et al. Nutrient intake and cataract extraction in women: a prospective study. BMJ. 1992;305:335-339.

156 Kuklinski B., Zimmermann T., Schweder R. Reducing the lethality in acute pancreatitis with sodium selenite. Med Klin. 1995;90:36-41.

157 Kuklinski B., Buchner M., Schweder R., et al. Acute pancreatitis. A free radical disease. decrease of lethality by sodium selenite therapy. Z Gesamte Inn Med. 1991;46:S145-S149.

158 Geusens P., Wouters C., et al. Long-term effect of omega-3–fatty acid supplementation in active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthr Rheum. 1994;37:824-829.

159 Yau T.M., Weisel R.D., Mickle D.A.G., et al. Vitamin E for coronary bypass operations. A prospective, double-blind, radomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:302-310.

160 Ferreira R.F., Milei J., Llesuy S., et al. Antioxidant action of vitamins A and E in patients submitted to coronary artery bypass surgery. Vascular Surgery. 1991;25:191-195.

161 Knekt P., Reunanen A., et al. Antioxidant vitamin intake and coronary mortality in a longitudinal population study. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1180-1189.

162 Castilloduran C., Rodriguez A., Venegas G., et al. Zinc supplementation and growth of infants born small for gestational age. J. Paediatrics. 1995;127:206-211.

163 Lohr J.B., Caligiuri M.P. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of vitamin E treatment of tardive dyskinesia. J of Clin Psych. 1996;57(4):167-173.

164 Gatto L.M., Hallen G.K., Brown A.J., et al. Ascorbic acid induces a favourable lipoprotein profile in women. J Amer Coll Nutr. 1996;15(2):154-158.

165 Terezhalmy G.T. The use of water-soluble bioflavinoid-ascorbic acid complex in the treatment of recurrent Herpes Labialis. Oral Surgery. 1978;45(1):56-62.

166 Autier P., Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(16):1730-1737.

167 Kim J.M., White R.H. Effect of vitamin E on the anticoagulant response to warfarin. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(7):545-546.

168 Liede K.E., Haukka J.K., Saxen L.M., et al. Increased tendency towards gingival bleeding caused by joint effect of alpha-tocopherol supplementation and acetylsalicylic acid. Ann Med. 1998;30:542-546.

169 Paolisso G., D’Amore A., Giugliano D., et al. Pharmacologic doses of vitamin E improve insulin action in healthy subjects and non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients. AJCN. 1993;57:650-656.

170 Ward N.C., Hodgson J.M., Puddey I.B., et al. Vitamin E increases blood pressure in type 2 diabetic subjects, independent of vascular function and oxidative stress. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2005;14(suppl):S41.

171 Bjelakovic G., Nikolova D., Gluud L.L., et al. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;297:842-857.

172 Milman U., Blum S., Shapira C., et al. Vitamin E supplementation reduces cardiovascular events in a subgroup of middle-aged individuals with both type 2 diabetes mellitus and the haptoglobin 2–2 genotype. A prospective double-blinded clinical trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007. ATVBAHA.107.153965

173 Burke K.E. Interaction of vitamins C and E as better cosmeceuticals. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20(5):314-321.

174 Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

175 Cole B.F., Baron J.A., Sandler R.S., et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2351-2359.

176 Mason J.B., Dickstein A., Jacques P.F., et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidem Biom Prevent. 2007;16:1325-1329.

177 Stevens V.L., Rodriguez C., Pavluck A.L., et al. Folate nutrition and prostate cancer incidence in a large cohort of US men. Amer J Epidemiol. 2006;163:989-996.

178 Hubner R.A., Houlston R.S. Folate and colorectal cancer prevention. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(2):233-239.

179 Wandzilak T., D’Andre S., Davis P., et al. Effect of High Dose Vitamin C on Urinary Oxalate Levels. J Urol. 1994;151:834-837.

180 Drisko J.A., Chapman J., Hunter V.J. The use of antioxidant therapies during chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;88:434-439.

181 Li T.S., Marban E. Physiological levels of reactive oxygen species are required to maintain genomic stability in stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010:4. May

182 Underwood B. Maternal Vitamin A status and its importance in infancy and early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:517S-524S.

183 Bardia A., Imad M., Tleyjey I.M., et al. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research efficacy of antioxidant supplementation in reducing primary cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:23-34.

184 Leitzmann M.F., Stampfer M.J., Wu K., et al. Zinc supplement use and risk of prostate cancer. JNCI. 2003;95:1004-1007.

185 Food and Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine. Magnesium. Dietary Reference Intakes: Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1997. 190–249. [National Academy Press]

186 Food and Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine. Chromium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001. 197–223

187 Mulyani I., Levina A., Lay P.A. Biomimetic oxidation of chromium (III): Does the antidiabetic activity of chromium (iii) involve carcinogenic chromium(vi). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:4504-4507.

188 The prevalence and severity of iodine deficiency in Australia. Prepared for the Australian Population Health Development Principal Committee of the Australian Health Ministers Advisory Committee December, 2007. Online. Available: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/_srcfiles/Item%2002%2005%20–%20Attachment%201%20–%20%20Prevalence%20and%20severity%20of%20iodine%20deficiency%20in%20Australia.pdf#search=%22iodine%22 (accessed 02-02-09).

189 Verheesen R.H., Schweitzer C.M. Iodine deficiency, more than cretinism and goiter. Med Hypotheses. 2008 November;5(71):645-648.

190 New England J of Med, 2009.

191 Gorduza E.V., Indrei L.L., Gorduza V.M. Nutrigenomics in postgenomic era. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2008;112(1):152-164.