Nutritional assessment

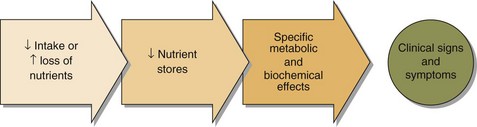

Malnutrition to the layman usually means starvation, but the term has a much wider meaning encompassing both the inadequacy of any nutrient in the diet as well as excess food intake. The pathogenesis of malnutrition is shown in Figure 52.1.

Malnutrition related to surgery or following severe injury occurs because of the extensive metabolic changes that accompany these events: the ‘metabolic response to injury’ (pp. 110–111).

The assessment of a patient suspected of suffering from malnutrition is based on:

Biochemistry

Protein. Serum albumin concentration is a widely used but insensitive indicator of protein nutritional status. It is affected by many factors other than nutrition, e.g. hepatic and renal diseases and the hydration of the patient. Serum albumin concentration rapidly falls as part of the metabolic response to injury, and the decrease may be mistakenly attributed to malnutrition.

Protein. Serum albumin concentration is a widely used but insensitive indicator of protein nutritional status. It is affected by many factors other than nutrition, e.g. hepatic and renal diseases and the hydration of the patient. Serum albumin concentration rapidly falls as part of the metabolic response to injury, and the decrease may be mistakenly attributed to malnutrition.

Blood glucose concentration. This will be maintained even in the face of prolonged starvation. Ketosis develops during starvation and carbohydrate deficiency. Hyperglycaemia is frequently encountered as part of the metabolic response to injury.

Blood glucose concentration. This will be maintained even in the face of prolonged starvation. Ketosis develops during starvation and carbohydrate deficiency. Hyperglycaemia is frequently encountered as part of the metabolic response to injury.

Lipids. Fasting plasma triglyceride levels provide some indication of fat metabolism, but are again affected by a variety of metabolic processes. Essential fatty acid levels may be measured if specific deficiencies are suspected. Faecal fat may be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively in the assessment of malabsorption. However this test is not commonly available, and is certainly not popular with laboratory staff.

Lipids. Fasting plasma triglyceride levels provide some indication of fat metabolism, but are again affected by a variety of metabolic processes. Essential fatty acid levels may be measured if specific deficiencies are suspected. Faecal fat may be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively in the assessment of malabsorption. However this test is not commonly available, and is certainly not popular with laboratory staff.

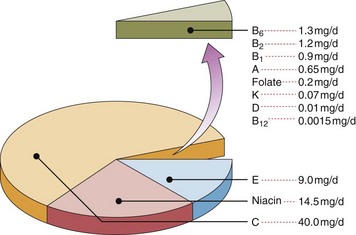

Vitamins. These organic compounds are vital for normal metabolism. Usually they are classified by their solubility; they are listed in Table 52.1 and their average adult daily requirements shown in Figure 52.2. Some assays are available to measure the blood levels of vitamins directly, but often functional assays that utilize the fact that many vitamins are enzyme cofactors are used. These latter assays may help identify gross abnormalities. However, to detect subtle deficiencies and the increasing problem of excess intake, quantitative measurements are required.

Vitamins. These organic compounds are vital for normal metabolism. Usually they are classified by their solubility; they are listed in Table 52.1 and their average adult daily requirements shown in Figure 52.2. Some assays are available to measure the blood levels of vitamins directly, but often functional assays that utilize the fact that many vitamins are enzyme cofactors are used. These latter assays may help identify gross abnormalities. However, to detect subtle deficiencies and the increasing problem of excess intake, quantitative measurements are required.

Table 52.1

| Vitamins | Deficiency state | Lab assessment |

| Water soluble | ||

| C (Ascorbate) | Scurvy | Plasma or leucocyte levels |

| B1 (Thiamin) | Beri-beri | Red cell levels |

| B2 (Riboflavin) | Rarely single deficiency | Red cell levels |

| B6 (Pyridoxine) | Dermatitis/Anaemia | Red cell levels |

| B12 (Cobalamin) | Pernicious anaemia | Serum B12, full blood count |

| Folate | Megaloblastic anaemia | Serum folate, RBC folate, full blood count |

| Niacin | Pellagra | Urinary niacin metabolites (not commonly available) |

| Fat soluble | ||

| A (Retinol) | Blindness | Serum vitamin A |

| D (Cholecalciferol) | Osteomalacia/rickets | Serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol |

| E (Tocopherol) | Anaemia/neuropathy | Serum vitamin E |

| K (Phytomenadione) | Defective clotting | Prothrombin time |

Major minerals. These inorganic elements are present in the body in quantities greater than 5 g. The main nutrients in this category are sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. All of these are readily measurable in blood and their levels in part reflect dietary intake.

Major minerals. These inorganic elements are present in the body in quantities greater than 5 g. The main nutrients in this category are sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. All of these are readily measurable in blood and their levels in part reflect dietary intake.

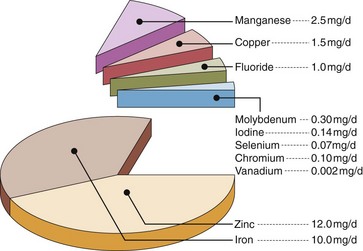

Trace elements. Inorganic elements present in the body in quantities less than 5 g are often found in complexes with proteins. The essential trace elements are shown in Figure 52.3.

Trace elements. Inorganic elements present in the body in quantities less than 5 g are often found in complexes with proteins. The essential trace elements are shown in Figure 52.3.