Pathway to career goals.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

• Compare the various types of educational preparation for nursing.

• Describe the educational preparation for a graduate degree.

• Compare nontraditional pathways of nursing education.

• Describe the purpose of nursing program accreditation.

• Set personal educational goals for yourself.

Education should not be a destination—but a path we travel all the days of our lives.

Anonymous

Unless we are making progress in our nursing every year, every month, every week, take my word for it we are going back.

Florence Nightingale

What an exciting time to be a nurse. Never before have the doors been so open for nurses to further their education. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (2010), set forth recommendations that would change the future of nursing and nursing education in ways never dreamed possible. Recommendation 4 discussed increasing the number of nurses with baccalaureate degrees to 80% by the year 2020, whereas Recommendation 5 proposed to double the number of nurses with doctorate degrees by 2020. Recommendation 6 explained the need for nurses to engage in lifelong learning. Based on these three recommendations alone, educational systems across the country began diligently brainstorming and working collaboratively to address these goals.

A Joint Statement on Academic Progression for Nursing Students and Graduates (2012) was made by the Tri-Council for Nursing policy (2010) and endorsed by both community college–registered and university-registered nursing programs with the understanding that both student nurses and practicing nurses need to be encouraged and supported to achieve higher levels of education (AACN, 2012a). What does all this mean to you as a nurse? It means that educational programs as well as employers throughout the country are striving to find ways to make it easier for nurses to further their education. More community colleges and universities are expanding their nursing programs to meet the needs for health care reform. Add to this the advancing computer technology that makes it easier to provide comparable education via distance learning and simulation, and you have an environment that beckons nurses to further their education. Whatever your basic nursing education program, you will now find it easier to advance in your profession. Instead of seeing roadblocks, you will see more doors and windows opened to allow you to advance your education. Are you ready for the challenge?

After struggling to complete your basic educational preparation for nursing, you are probably looking forward to that first paycheck as a registered nurse. The last thing on your mind is returning to school for more education! The purpose of this chapter is not to discuss the issue of entry into practice or to debate which educational program is best. Instead, the goal of this chapter is to help you look at where you are educationally and to offer direction regarding educational opportunities to enhance your career goals and to continue on the path of lifelong learning. Before looking down the path at the variety of educational offerings available to help you meet those goals, let us look at the variety of pathways that lead to the basic educational preparation for an RN.

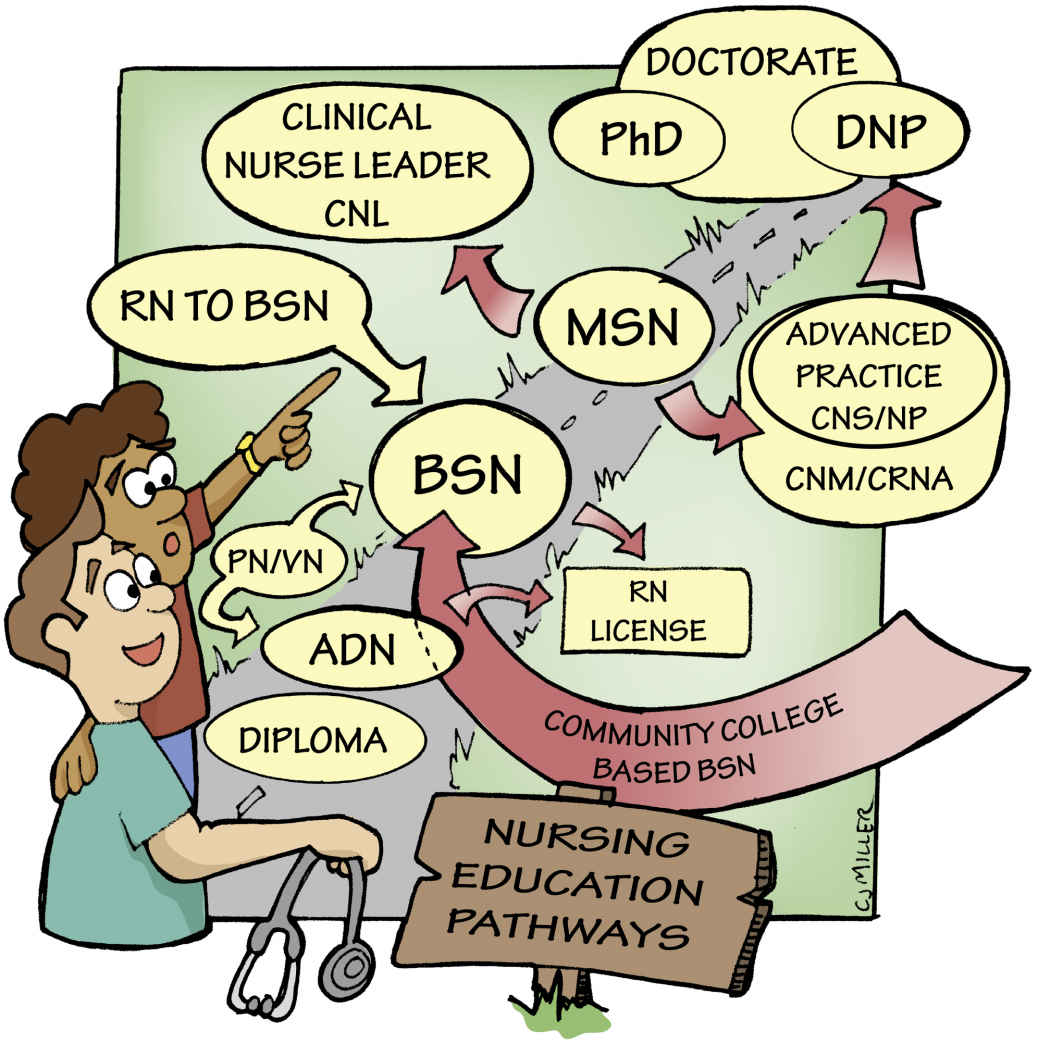

Which path did you travel? There are three primary paths (diploma, associate’s degree, and bachelor’s degree) that lead to one licensing examination: the National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN® Examination). These programs usually require a high school diploma or the equivalent for admission. Some of the other paths include master’s and doctoral nursing degree programs, both of which accept college graduates with liberal arts majors. Other paths are becoming more popular, including career ladder programs (from practical nurse to associate degree or baccalaureate degree nurse), concurrent enrollment program (from associate’s degree to bachelor’s degree), accelerated baccalaureate program for non-nursing college graduates, entry-level master’s and doctorate programs, and community college–based BSN programs. Still another source for nursing education is the online option. Online programs are particularly popular for people who are place-bound and unable to travel to distant sites to obtain or continue their education. Some of these programs require brief visits to a campus, whereas others are completely online.

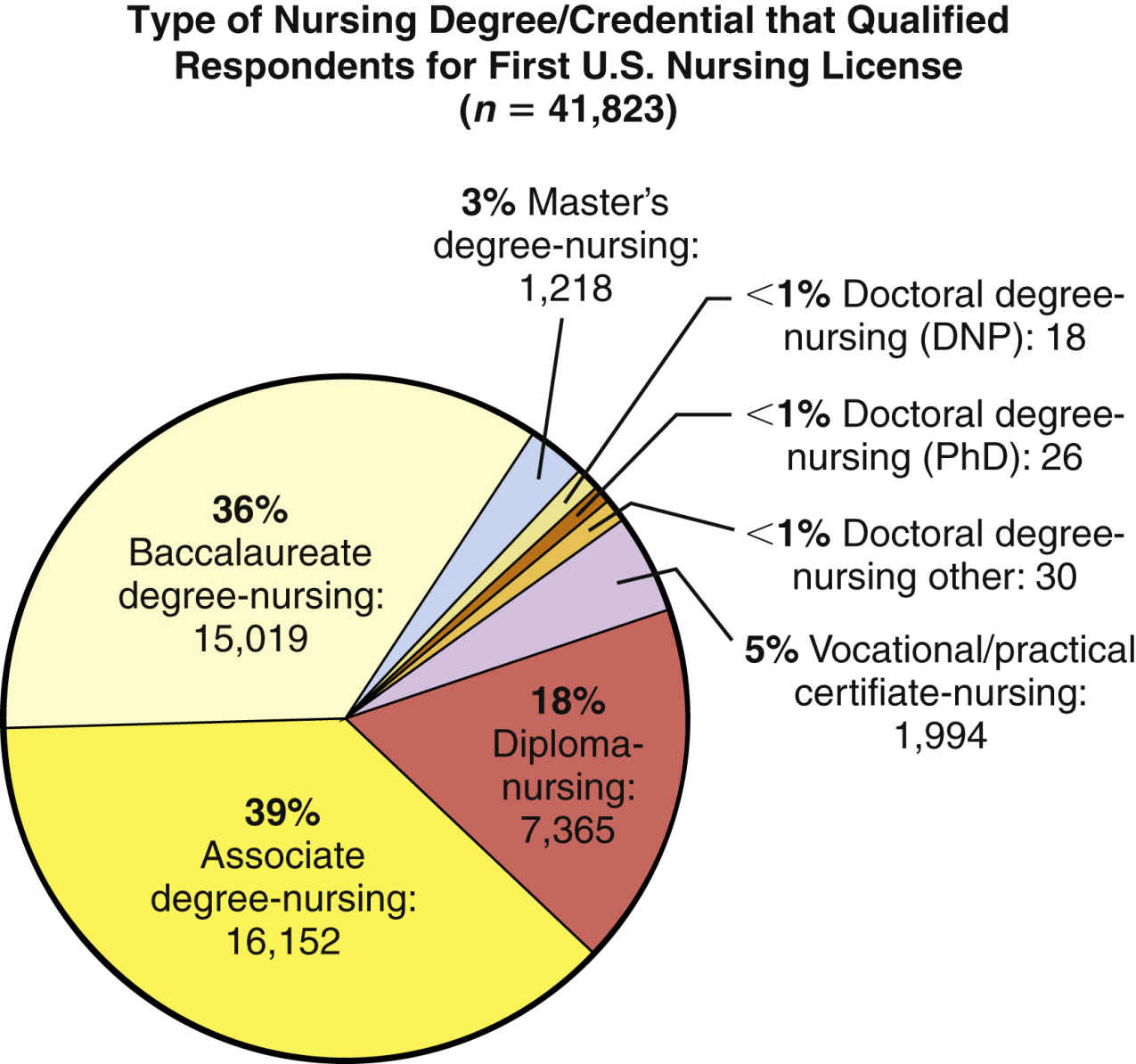

The distribution of the RN population according to basic nursing education is illustrated in Fig. 7.1. In 1980, the diploma education track was the highest level of education for most nursing graduates. Since 1996, there has been a continued increase in the number of RNs receiving their initial preparation in either an associate’s degree or a baccalaureate program. The National Workforce Survey of Registered Nurses (2013) indicates that initial preparation in a diploma program accounted for 18%, the associate’s degree accounted for 39%, and the baccalaureate degree program accounted for 36% of the registered nurses. Furthermore, it is estimated that 3% of RNs received their initial nursing education at either a master’s or doctoral level (Budden et al., 2013, p.7).

Path of Diploma Education

What Is the Educational Preparation of the Diploma Graduate?

The current preparation of a diploma nurse varies in length from 2 to 3 years and takes place in a hospital school of nursing. This type of program may be under the direction of the hospital or incorporated independently. The diploma program may include general education subjects such as biology and physical and social sciences, in addition to nursing theory and practice. Graduates of diploma programs are prepared to function as beginning practitioners in acute, intermediate, long-term, and ambulatory health care facilities. Because there is a close relationship between the nursing school and the hospital, graduates are well prepared to function in that institution. On graduation, many diploma graduates are employed by that same hospital and therefore may experience an easier role transition.

FIG. 7.1 Type of nursing degree/credential that qualified respondents for first U.S. nursing license. (Adapted from Budden, J., Zhong, E., Moulton, P., & Cimioti, J. (2013). Highlights of the national workforce survey of registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 4(2), 5–13.)

Standards and competencies for diploma programs are developed and maintained by the National League for Nursing (NLN) Council of Diploma Programs. Graduates of diploma programs are awarded a certificate and are eligible to take the NCLEX-RN® Examination for licensure.

Path of Associate Degree Education

What Is the Educational Preparation of the Associate Degree Graduate?

The current preparation of an associate degree nurse usually begins in a community college, although some programs are based in senior colleges or universities. The associate degree program lasts 18 to 21 school calendar months. The NLN recommends that associate degree nursing programs consist of 60 to 72 semester credits (90 to 108 quarter credits) and that there is a balanced distribution of no more than 60% of the total number of credits allocated to nursing courses (NLN, 2001). In some programs, the student must complete the general education and science course requirements before beginning the nursing courses. At the end of the program, the student receives an associate’s degree in nursing (ADN) or Associate in Applied Science (ASN or AAS).

Associate degree nursing education has helped to bring about a change in the type of student who enrolls in nursing programs. Before the emergence of associate degree nursing programs, nursing students were traditionally single white females younger than 19 years of age who came from middle-class families (Kaiser, 1975). Associate degree programs attract a more diverse student population that includes older individuals, minorities, men, and married women from a variety of educational and economic backgrounds. Many of these individuals have baccalaureate and higher degrees in other fields of study and are seeking a second career. Along with their maturity, these students bring life experiences that are applicable to nursing. The students tend to be more goal oriented and have a more realistic perspective of the work setting. The community college curriculum is conducive to students who want to attend school on a part-time basis. Graduates of associate degree programs are eligible to take the NCLEX-RN® examination for licensure.

Dr. Montag’s (1951, 1959) original proposal for the associate degree program to be a terminal degree is no longer applicable. In 1978, the American Nurses Association proposed a resolution regarding associate degree programs that recommended they be viewed as part of the career upward-mobility plan rather than as terminal programs. Recommendation 4 of the recent IOM report, proposing to increase to 80% by 2020 the proportion of nurses with BSN degrees, further supports the need for ADNs to consider advancing their educations (IOM, 2010). The associate degree program has provided students with the motivation to further their education and the opportunity for career mobility. Although many nursing students end their education with an associate’s degree, many others enter the associate degree program with every intention of continuing their nursing education to the baccalaureate level or even further.

Path of Baccalaureate Education

In this discussion, only the “generic” baccalaureate programs are addressed. A generic student is one who enters a baccalaureate nursing program with no training or education in nursing. A traditional generic baccalaureate program includes lower-division (freshman and sophomore) liberal arts and science courses with upper-division (junior and senior) nursing courses. RNs entering baccalaureate programs are discussed later in this chapter.

What Is the Educational Preparation of the Baccalaureate Graduate?

The current preparation of a baccalaureate nurse is 4 to 5 years in length (120 to 140 credits) and emphasizes courses in the liberal arts, sciences, and humanities. Approximately one-half to two-thirds of the curriculum consists of non-nursing courses. To qualify for a baccalaureate program, the student must first meet all of the college’s or the university’s entrance requirements. Usual entrance requirements include college preparation courses in high school (e.g., foreign language, advanced science, and math courses) and a specified cumulative grade-point average (GPA). Most colleges also require a college entrance examination such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) or the American College Test (ACT).

During the first 2 years of a traditional baccalaureate nursing program, the student is usually enrolled in liberal arts and science courses with other non-nursing students. It is usually not until late in a student’s sophomore or early junior year that nursing courses are introduced. However, some baccalaureate programs incorporate nursing courses throughout the 4-year nursing curriculum. The emphasis in the baccalaureate nursing program is on developing critical decision-making skills, exercising independent nursing judgment, and acquiring research skills.

The graduate of a baccalaureate program must fulfill both the degree requirements of the nursing program and those of the college. On completion of the program, the usual degree awarded is a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN).

The graduate of a baccalaureate program is prepared to provide health promotion and health restoration care for individuals, families, and groups in a variety of institutional and community settings. Graduates of baccalaureate nursing programs are eligible to take the NCLEX-RN® examination for licensure. BSN graduates are also prepared to continue their education by moving directly into graduate education. An increasing number of BSN graduates are continuing their nursing education by going directly into graduate programs.

Other Types of Nursing Education

What Are the Other Available Educational Options?

In the 1960s, baccalaureate programs made it very difficult for the RN to return to school to earn a baccalaureate in nursing. Most of the time, these nurses found themselves receiving no credit for their past education or experience. A resolution was passed in 1978 by the American Nurses Association (ANA) that helped to change this philosophy. This resolution urged the creation of quality career-mobility programs with flexibility to assist individuals desiring academic degrees in nursing. Following the IOM report, developers of nursing educational programs have been challenged to rethink nursing education. The Tri-Council’s 2010 statement for access to nursing education for all nurses, providing for a seamless academic progression (AACN, 2012a), has further widened the pathways toward advanced education. It is anticipated that nursing education will be transformed to create a health care workforce that is better prepared in ways that can only be imagined at this time.

Besides the traditional pathways for entering the nursing profession such as diploma, associate degree, and baccalaureate programs, new pathways are emerging. Entry-level master’s programs, accelerated programs for non-nursing graduates, community college–based baccalaureate programs, and registered nurse degree completion programs for licensed practical nurses and other health care providers are a few of the many options, and it is anticipated that there may be others in the near future.

Just as there are new pathways to enter the nursing profession, there are also new pathways for those nurses who are interested in advancing their nursing education including baccalaureate to doctoral programs, master’s degrees for advanced generalist roles, such as the clinical nurse leader (CNL), as well as the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP).

It truly is an exciting time to be in nursing, and there is no one right career pathway for everyone. Each person needs to consider what his or her professional end goal is and what works best for him or her. Is an online program that provides more flexibility in scheduling for family and work obligations the best choice or perhaps a blended or hybrid program? Is the program respected in the nursing community and known for producing great nurse educators, researchers, or advanced practice nurses? Is it an accredited program? Will course work transfer? It is important to ask yourself what you are willing to invest in your education besides the time and monetary expenses.

In assessing the available educational options, one source of information is the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) website (http://www.aacn.nche.edu/students). There is a section for students that includes information on nursing careers, financial aid, scholarships, and nursing programs. Potential students should also contact individual schools for information regarding their particular programs. After you are ready to begin the application process, you will also find that the Nursing Centralized Application Service (CAS) has simplified the process by providing a service for students to use to apply to nursing programs at participating schools nationwide (http://www.aacn.nche.edu/nursingcas). At the end of this chapter is a complete list of additional relevant websites and online resources for advancing your nursing education.

The career ladder or bridge concept focuses on the articulation of educational programs to permit advanced placement without loss of credit or repetition. There are many variations on this type of program. Multiple-exit programs provide opportunities for students to exit and reenter the educational system at various designated times, having gained specific education and skills. An example is a program that ranges from practical nurse to RN at the associate’s, baccalaureate, master’s, and doctoral levels. A student in such a program may decide to leave the educational system at the completion of a specific level and be eligible to take the licensure examination applicable to that educational level. On termination, the student may choose to work for a while and later return for more education at the next level without having to repeat courses on previously acquired knowledge or skills. Information on the three types of articulation agreements— individual, mandated, and statewide—can be found on the AACN website. Growing numbers of basic nursing education programs within the community college setting are beginning to offer career ladder programs and concurrent enrollment programs, affiliating themselves with upper-division colleges in the area. A student can enter the community college to spend 1 year studying to become a practical or vocational nurse. After a year, the student can decide to stop and take the practical nurse licensure examination or continue and complete the associate’s degree in nursing. At the end of the second year, the student is eligible to take the RN licensure examination and may choose either to exit with an associate’s degree or to attend an affiliated upper-division college to obtain a bachelor’s degree (Fig. 7.2).

What Is a BSN/MSN Completion Program?

A BSN-completion program is a baccalaureate program designed for students who already possess either a diploma or an associate’s degree in nursing and hold a current license to practice as an RN. Depending on the part of the country, these programs may also be known as RN baccalaureate (RNB) programs, RN/BSN programs, baccalaureate RN (BRN) programs, two-plus-two programs, or capstone programs. There are more than 679 BSN-completion programs. In addition to the BSN-completion programs, 209 RN-to-master’s degree program options are available, and there are 28 additional nursing schools planning to implement a BSN and 31 planning to implement an MSN completion program in the near future (AACN, 2015c). In most of these programs, nurses receive transfer credit in basic education courses taken at other institutions plus either some transfer credit for their previous nursing courses or the opportunity to receive nursing credit by passing a nursing challenge examination.

The usual length of such programs is 1 to 3 years, depending on the number of course requirements completed at the time of admission to the program. To meet the needs of the returning student, many BSN-completion programs offer flexible class scheduling, which allows the student to continue working while going to school. Another innovation being implemented to address the needs of individuals seeking baccalaureate degrees in outlying geographic areas is telecommunication-assisted studies and Internet courses. More than 400 programs have part of their curriculum online, whereas an increasing number of programs are available completely online (AACN, 2015c).

What Is an External Degree Program?

In the early 1970s, the external degree program was a nontraditional program that allowed a student to gain credit, meet external degree requirements, and obtain a degree from a degree-granting institution without attending face-to-face classes. One of the earliest external degree (or distance education) programs was offered through the New York Board of Regents external degree programs (REX), which is now Excelsior College. External degree programs may offer an ADN as well as a BSN and a master of science in nursing (MSN). These programs are designed to allow individuals to obtain degrees in nursing without leaving their jobs or their communities.

Nursing education online is a rapidly expanding part of the Internet. In the past these programs were called external degree or distance education; however, more commonly now the programs are considered nursing online education. Online nursing programs are accredited either by the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) (formerly the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission [NLNAC]), National League for Nursing Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation (CNEA), or by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE), which is an autonomous accrediting agency associated with the AACN. In the undergraduate nursing programs, all students are required to pass specific college-level tests and performance examinations in two components: general education and nursing. On completion of the undergraduate external degree programs, students are eligible in most states to take the RN licensure exam. One of the largest CCNE-approved programs for BSN completion and graduate education is the University of Phoenix online campus.

Online (Web-Based) Programs

More and more traditional colleges and universities are offering courses and even entire programs through the Internet. In fact, it is possible to earn ADN, BSN, master’s, and doctoral degrees in web-based or web-enhanced formats. At times, it can be confusing and overwhelming to find the right programs. Several sites are available to help users locate specific web-based or web-enhanced courses (and course descriptions). See the Internet resources listed on this book’s Evolve website. It is important to take into consideration the cost not only of an online program but also of out-of-state tuition when considering which program is the best fit for your career goals.

Proprietary Nursing Schools

In addition to the colleges and universities that are offering these types of courses, an influx of new proprietary nursing programs has emerged. A proprietary nursing school is a for-profit school with a nursing program. Many proprietary schools have nursing programs in more than one state. Since not all nursing boards have the same requirements for licensure, it is important to review the requirements in your state to make sure that you will be eligible for licensure once you complete the program. A prospective student should also make sure that the program is accredited and ask about the pass rates on the NCLEX examination for their graduates.

What Is an Accelerated Program?

Accelerated programs are offered at both the baccalaureate and master’s degree levels; they are designed to build on previous learning to help a person with an undergraduate degree in another discipline make the transition into nursing. In 2013, there were 293 accelerated baccalaureate programs and 62 accelerated master’s programs available at nursing schools nationwide. In addition, 13 new accelerated baccalaureate programs are in the planning stages, and 9 new accelerated master’s programs are also taking shape (AACN, 2015b).

Nontraditional Paths for Nursing Education

What About a Master’s Degree as a Path to Becoming an RN?

MSN programs are particularly attractive to the growing number of college graduates who decide later in life to enter nursing. Generally, the program is 24 to 36 months long. Upon graduation these students are expected to demonstrate the same entry-level competencies in nursing as baccalaureate graduates. MSN graduates from these programs are then eligible to take the NCLEX-RN® examination. Currently, there are 62 entry-level master’s programs in the United States (AACN, 2015b).

What About a Doctoral Path to Becoming an RN?

The last and least common path leading to the RN licensure examination is the doctoral degree, where the graduate has a non-nursing baccalaureate degree. This program began in 1979 at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Rush University in Chicago initiated a similar program in 1988, and the University of Colorado began one in 1990 (Forni, 1989). These programs, such as the one at the University of Texas at Austin, provide basic nursing courses, along with advanced nursing courses. Upon completion, the graduate is eligible to take the NCLEX-RN® examination. There are currently 81 baccalaureate to research-focused doctoral programs (PhD) and 153 practice-focused baccalaureate to doctoral programs (DNP) (AACN, 2014a).

Graduate Education

What About Graduate School?

Whatever path you chose to become an RN, one thing was certain: It was not easy! After putting life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness on hold while you worked toward becoming an RN, it may seem like pure insanity to subject yourself to more education!

Graduate nursing education, like other graduate programs, is responding to changes in social values, priorities in the public sector, and student demographics, in addition to technological advances, knowledge development, and maturity of the profession. According to the 2013 National Nursing Workforce Survey of Registered Nurses (NCSBN, 2013), there is an increase in the percentage of nurses who indicate a BSN as their initial education. Approximately 36% reported their initial education as BSN, while 3% reported their initial education as a graduate degree. After initial licensure, 24% of the nurses went on to receive advanced formal education (NCSBN, 2013), indicating that RNs in the workforce are recognizing the need for additional education and are returning to college to further their education either in nursing or nursing-related fields such as public health and health care administration.

Graduate education programs are available on either a part-time or a full-time basis. Graduate programs require a good GPA at the undergraduate level. Prerequisites for most graduate programs are satisfactory scores on the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) or the Miller Analogies Test (MAT). Although an increasing number of graduate programs are waiving the entrance examination requirements, it is strongly recommended that all students, whether they plan to pursue graduate studies or not, take the GRE after completing their undergraduate studies. Taking another test may be the last thing you want to do, but it is much easier to do it now, while the information is current in your mind, than later when you decide that you want to continue your education.

Why Would I Want a Master’s Degree?

Sure, an advanced degree may not be in your career plans right now, but later, after you have been practicing nursing, you may change your mind. Policy statements from the nursing profession reflect the need for more education in preparation for the changing role of nursing, a result of health care reform. As care delivery moves increasingly from the acute care center to the community setting, there will be an increased need for advanced clinical practice nurses. Nursing programs are already responding to this changing need.

Master’s nursing programs vary from institution to institution, as do the admission and course requirements and costs. The master of science (MS) and the master of science in nursing (MSN) are the most common degrees. The usual requirements for admission include a baccalaureate degree from an ACEN, CCNE, or Commission on Nursing Education Accreditation (CNEA, the accrediting body of the NLN since 2013) accredited program in nursing, licensure as a registered nurse, completion of the GRE or MAT, and a minimum undergraduate GPA of 3.0.

The majority of programs are at least 18 to 24 months of full-time study. Unlike undergraduate students, master’s students usually choose an area of role preparation, such as education or administration, as well as an area of clinical specialization, such as pediatrics or adult health. Some of the more common areas of role preparation include education, administration, case management, health policy/health care systems, informatics, and the increasingly popular advanced clinical practice roles.

An evolving area of role preparation is that of the clinical nurse leader (CNL). The CNL role is different from the role of manager or administrator. The CNL is prepared at the master’s level as a generalist managing the health care delivery system across all settings. Any person interested in the CNL role is encouraged to read the Competencies and Curricular Expectations for Clinical Nurse Leader Education and Practice (AACN, 2013) found on the AACN website. Upon completion of a formal CNL program, a graduate is eligible to take the CNL Certification Examination. In Fall 2014/Winter 2015, 109 of 229 nurses taking the CNL certification exam passed, for a pass rate of 68% (AACN, 2015a).

Areas of specialty within the master’s nurse practitioner programs include family, acute care, pediatric, psychiatric, and adult-gerontology nursing practice. There are more family nurse practitioner programs than any other program. The AACN supported the position of the practice doctorate (DNP) as the entry level for the advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) by the year 2015 (AACN, 2015d). Although there is a growing number of DNP programs, less than 25% of the schools with nurse practitioner programs have met this goal (Martsolf et al., 2015). An excellent resource for nurses who are considering becoming an APRN can be found at the American Association of Nurse Practitioners website http://www.aanp.org/education/student-resource-center/planning-your-np-education.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing APRN Advisory Committee and leading professional nursing organizations formed an APRN Consensus Work Group to work toward establishing clear expectations for LACE (licensure, accreditation, certification, and education) for APRNs. This work group has been meeting for several years, and in July 2008 the landmark document, Consensus Model for APRN Regulation: Licensure, Accreditation, Certification, & Education, was finalized. This document will be used to shape the future of APRN practice across the nation and to allow APRNs to practice to the full extent of their education. APRNs will be educated in one of the four roles, certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), or certified nurse practitioner (CNP), and in at least one of six population foci: family/individual across the lifespan, neonatal, pediatrics, adult-gerontology, women’s health/gender-related, or psych/mental health. All four of these roles will be given the title of advanced practice registered nurse (APRN). It is important for all potential APRNs to read this document, because it will change how APRNs are educated in the future (www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/APRNReport.pdf). See Table 7.1 for typical educational preparation and responsibilities of various advanced practice nurses.

According to The U.S. Nursing Workforce: Trends in Supply and Education report (2013), there has been a rapid growth of 69% in the number of nurse practitioner graduates from 7261 in 2001 to 12,273 in 2011. During that same time period, there also was a 111.1% increase in CRNAs from 1159 to 2447 graduates, although CNMs have not experienced as much of an increase from 285 in 2007 to nearly 400 in 2011.

In the more traditional master’s degree programs, the student takes the courses required for the degree and then, depending on institutional requirements, may also be required to take a written or oral comprehensive examination or write a thesis, or both. There are also nontraditional models that include outreach programs, summers-only programs, and programs for RNs who have bachelor’s degrees in other fields.

Advances in technology have also made it possible for graduate programs to become more creative in the way courses are being offered. It is now possible for students to obtain all or part of their course offerings by means of the Internet, distance learning, computer-based programs, and teleconferencing. This flexibility makes it easier for students in rural communities and part-time students to obtain advanced degrees.

TABLE 7.1

| Education | What they Do | |

| Nurse practitioner (NP) | Most of the approximately 350 NP education programs in the United States today confer a master’s degree. In the future, the DNP will be the entry level for an NP. The majority of states require NPs to be nationally certified by ANCC, ACNP, or a specialty nursing organization. In 2014, more than 205,000 of advanced practice nurses were NPs. | Working in clinics, nursing homes, hospitals, HMOs, private industry or their own offices, NPs are qualified to handle a wide range of basic health problems. Most have a specialty—for example, an adult, family, or pediatric health care degree. At minimum, NPs conduct physical examinations, take medical histories, diagnose and treat common acute minor illnesses or injuries, order and interpret laboratory tests and radiographs, and counsel and educate patients. In all states they may prescribe medication according to state law. Some work as independent practitioners and can be reimbursed by Medicare or Medicaid for services rendered. |

| Certified nurse-midwife (CNM) | An average 1.5 years of specialized education beyond nursing school, either in an accredited certificate program or at the master’s level. In 2015, there were an estimated 11,018 nurses prepared as CNMs in the United States (ACNM, 2015). | CNMs are well known for delivering babies in hospitals, homes, well-woman gynecological and low-risk obstetrical care, including prenatal, labor and delivery, and postpartum care. The CNM manages women’s health care throughout the lifespan, including primary care, gynecological exams, and family planning. CNMs have prescriptive authority in all 50 states. |

| Clinical nurse specialist (CNS) | CNSs are registered nurses with advanced nursing degrees—master’s or doctoral—who are experts in a specialized area of clinical practice such as psychiatric/mental health, adult/gerontology, pediatric, women’s health, and neonatal health. There are approximately 72,000 CNSs in the United States (NACNS, 2014). | Most CNSs work in the hospital setting, full time, and have responsibility for more than one department. CNSs can also work in clinics, nursing homes, their own offices, and other community-based settings, such as industry, home care, and HMOs. They conduct health assessments, make diagnoses, deliver treatment, lead evidence-based practice projects, and develop quality-control methods. In addition to delivering direct patient care, CNSs work in consultation, research, education, and administration. Some work independently or in private practice and receive reimbursement. Based on state laws where the CNS practices, CNSs are authorized to prescribed medications (NACNS, 2014). |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) | CRNAs are registered nurses who complete a graduate program and meet national certification and recertification requirements. There are an estimated 39,410 CRNAs in the United States (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). | In this oldest of the advanced nursing specialties, CRNAs safely administer approximately 40 million anesthetics to patients each year in the United States. In some states, CRNAs are the sole anesthesia providers in rural hospitals (AANA, 2015). This enables health care facilities to provide obstetrical, surgical, and trauma stabilization services. CRNAs provide anesthetics to patients in collaboration with surgeons, anesthesiologists, dentists, podiatrists, and other qualified health care professionals. |

How Do I Know Which Master’s Degree Program Is Right for Me?

Your career goals and interests will help you to determine which choice is best for you. Do some reading on your area of special interest and find out how advanced education would help you to obtain your career goals. As an example, in most nursing programs, a nurse with a non-nursing master’s degree would need to complete a master’s in nursing to become an advanced practice nurse. If you think that you might want to become a nurse practitioner at some point in your life, be sure that you obtain your master’s in nursing. You can always go back and obtain a post-master’s certificate as a nurse practitioner. If your master’s degree is in another field, this may not be possible, as most programs require a master’s in nursing. Although the movement to change the entry level for an APRN to a DNP by the year 2015 did not materialize, it is important to note that this may be a reality in the future, and you might want to consider this as you set your educational goals.

After you have decided on a master’s degree, there are several resources available online, such as the Peterson’s Guide (www.petersons.com), to help you find the right school. Consider all the options, and do your homework. If you are considering an advanced practice degree, be sure to check with the Board of Nursing for the state in which you reside to see what the requirements are to be recognized as an APRN in your state. Believe it or not, the requirements are not the same for every state. After all, if you are going to expend the time, energy, and finances to obtain a graduate degree, you want to get the most from it.

Why Would I Want a Doctoral Degree?

Power, authority, and professional status are usually associated with a doctoral degree. Nurses with doctoral degrees provide leadership in the improvement of nursing practice and in the development of research and nursing education programs. It is no secret that the role of the nurse is changing and will continue to change as health care reform continues to be implemented. There is a growing need for administrators, policy analysts, clinical researchers, and clinical practitioners in the community and in governmental agencies. Nurses need to position themselves to take on these new leadership roles, and the way to do this is through advanced education, particularly at the doctoral level.

Until recently, there were two basic models of doctoral education in nursing: the academic degree, or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), and the professional degree, or Doctor of Nursing Science (DNS, DSN, or DNSc). For either of these degrees, you must first have a master’s in nursing. Nurses have other doctoral degree options available to them, such as the Doctor of Education (EdD), the Doctor of Public Health (DrPH), the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in a discipline other than nursing, the nontraditional external degree doctorate, and the practice-focused Nurse Doctorate (ND), which was initiated as an entry-level degree.

In October 2004, the AACN published a position statement on the practice doctorate in nursing (DNP). The term practice doctorate would be used instead of clinical doctorate, and the ND degree would be phased out. The DNP would become the educational preparation for all advanced practice nurses. This move toward a DNP is to take place throughout a 15-year period. There are currently 243 DNP programs with more than 70 additional nursing schools that are considering starting a DNP program (AACN, 2014a).

How Do I Know Which Doctoral Program Is Right for Me?

As with the master’s degree, it is important to look at your career goals before deciding which doctoral program is best for you. To help you with that task, look at the NLN and AACN publications specific to doctoral education. Ask yourself how much time you can devote to obtaining a doctorate degree. Can you be a full-time student, or must you continue to work? What do you plan to do with the degree after you obtain it?

Is there an institution available to you that offers a doctorate in nursing, or would you have to consider moving? What are your career and professional goals? Do you want to teach? The PhD is considered the research-focused degree. It prepares an individual for a lifetime of intellectual inquiry and has an increased emphasis on postdoctoral study. In contrast, the DNP is viewed as the practice-focused degree. The goal of this program is to prepare an advanced practitioner for the application of knowledge with an emphasis on research. The original intent of the DNS was to prepare nurses to perform clinical research. The August 2015 Report from the Task Force on the Implementation of the DNP (AACN) is an excellent resource for those considering a DNP.

At the end of this chapter are additional relevant websites and online resources for continuing your nursing education.

Credentialing: Licensure and Certification

What Is Credentialing?

In the early days of nursing before the Nightingale era, anyone could claim to be a nurse and practice the “trade” as he or she wished. It was only during the past century that nursing became a credentialed profession. A credential can be as simple as a written document showing an individual’s qualifications. A high school diploma is a credential that indicates a certain level of education has been attained. A credential can also signify a person’s performance. The attainment of a title—such as Fellow of the American Academy of Nursing (FAAN)—signifies excellence in performance; a postgraduate degree from an institution of higher learning (PhD or EdD) indicates success in terms of academic achievement and advanced nursing knowledge.

In nursing, the educational credentials that an individual holds indicate not only academic achievement but also the attainment of a minimum level of competency in nursing skills. An ADN, a diploma in nursing, or a baccalaureate degree in nursing (BSN or BS) represents academic achievement. After academic preparation and successful completion of the NCLEX, you will have a legal credential—your nursing license—that permits you to practice as an RN. Additional nursing credentials may reflect practice in special areas, such as Critical Care Registered Nurse (CCRN) and Certified Addictions Registered Nurse (CARN).

What Are Registration and Licensure?

Licensure affords protection to the public by requiring an individual to demonstrate minimum competency by examination before practicing certain trades. By 1923, 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii did not become states until much later) had some form of nursing licensure in place. Nursing licensure is a process by which a governmental agency grants “legal” permission to an individual to practice nursing. This accountability is maintained through state boards of nursing, which are responsible for the licensing and registration process. Boards of nursing vary in structure and are based on the design of the nurse practice act within each state. State boards of nursing also exercise legal control over schools of nursing within their respective states. In 1978, all boards of nursing formed a national council, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), to present a more collective front on nursing education and licensure.

Foreign nurse graduates who want to practice nursing in the United States must contact the board of nursing in the state in which they want to practice to obtain licensure, because each state controls its own requirements for licensure. The state’s board of nursing will review the candidate’s nursing education and determine requirements needed to obtain a license in that respective state. Most states require that foreign nurses take the Committee on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNS) examination before the NCLEX-RN® examination. This examination determines proficiency both in nursing and the English language, thus assisting in the prediction of success on the NCLEX-RN® examination. All foreign graduates, regardless of licensure in their home countries, must successfully complete the NCLEX-RN® examination.

What Is Certification?

In the classic article on credentialing published by the ANA in the late 1970s, certification is defined as a “voluntary process by which a nongovernmental agency or association certifies that an individual licensed to practice a profession has certain predetermined standards specified by that profession for specialty practice” (ANA, 1979, p. 67). Certification is a different credential from licensure and has a variety of interpretations—both for the nursing profession and the public.

The movement toward certification in nursing practice areas has grown significantly within the past 40 years. In 1946, credentialing was first required for entry into practice as a nurse anesthetist (i.e., CRNA). Twenty-five years later, nurse-midwives followed suit, needing certification through the American College of Nurse Midwives as an entry-level credential.

Since the establishment of the first certification program by the ANA in 1973, certification is the credential that provides recognition of professional achievement in a defined functional or clinical area of nursing practice. Credentials, such as professional certification, are the stamps of quality and achievement to communicate professional competence. The process of becoming certified engages a full circle of accountability to patients and families, along with professional colleagues. There are over 33 areas of specialty certification available from the ANCC (2014). In addition, magnet hospitals are more likely to have nurses that are specialty certified (McHugh et al., 2013).

What Is Accreditation?

The term accreditation is often confused with certification. The term is defined as “a process by which a voluntary, nongovernmental agency or organization approves and grants status to institutions or programs (not individuals) that meet predetermined standards or outcomes.” The accreditation of nursing programs by either the Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN) or the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) is an activity that you, the recent graduate, may have been involved with during your nursing education.

Accreditation is a peer-review and voluntary process. Member schools for the peer-review evaluation process support the use of standards and criteria. The process of accreditation is similar for both accrediting organizations—the CCNE and the ACEN. The National League for Nursing Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation (CNEA) is a newly formed accrediting body that will begin the process of accrediting all types of nursing programs (PN/VN, diploma, associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, post-master’s certificate, and clinical doctorate [DNP]) in 2016. The process of accreditation for NLN CNEA is similar to CCNE and ACEN.

Why should you be concerned whether the nursing program you are attending, or thinking about attending, is accredited? Accreditation assures you, the student, and the public that the program has achieved educational standards over and above the legal requirements of the state. It guarantees the student the opportunity to obtain a quality education. Accreditation is strictly a voluntary process. The U.S. Department of Education approves the professional association that is allowed to accredit nursing schools. Until 1997, the National League of Nursing (NLN) was the only accrediting body for nursing programs. In 1997 the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission (NLNAC) was established, and responsibility for all accrediting activities was transferred to this new independent subsidiary. In 2013 the name was changed to ACEN.

Some graduate nursing programs require completion of an ACEN or CCNE-approved undergraduate program as a prerequisite for admission to their master’s or doctoral program. Both the ACEN and CCNE publish annually an official complete list of accredited programs. Accreditation becomes a major concern as more and more courses and programs are offered by means of distance learning.

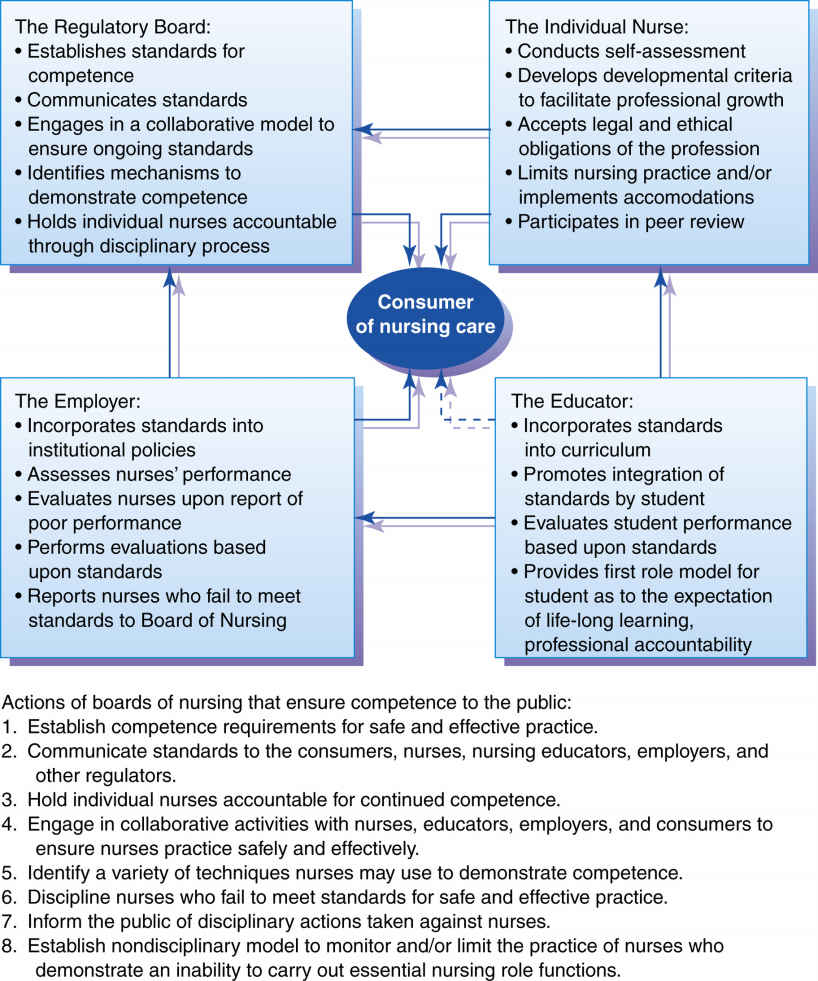

With different organizations offering accreditation to schools of nursing, it was difficult for schools of nursing to develop competency statements that were consistent. Rather than listing competency statements for three levels of nursing, the competency statement accepted by the 1996 annual meeting of the NCSBN is presented. According to the NCSBN, “Competence is defined as the application of knowledge and the interpersonal, decision-making and psychomotor skills expected for the practice role, within the context of public health, safety and welfare” (NCSBN, 1996, p 47). The NCSBN continues to work on the concept of continued competence as it explores its regulatory role.

The promotion of competency requires a collaborative approach; it involves the individual nurse, employers of nurses, nursing educators, and the regulating board of nursing. The roles of each of these in competence accountability are described in Fig. 7.3.

Nursing Education: Future Trends

Education is a lifelong process and an empowering force that enables an individual to achieve higher goals. Student access to educational opportunities is paramount to nursing education. A chapter on nursing education would not be complete without taking a look at the future.

The Changing Student Profile

Future nursing programs will need to be flexible to meet the learning needs of a changing student population. It has previously been stated that there is a growing population of nontraditional students—individuals who are making midlife career changes in part because of job displacement or job dissatisfaction. The student population tends to be older, married, and with families. Minority individuals, foreign students, and the poor are looking toward nursing education for career opportunities. There are a growing number of students choosing to attend school part time.

FIG. 7.3 Competence accountability. (From National Council of State Boards of Nursing (1996). Annual meeting. In Book of reports, Chicago: National Council of State Boards of Nursing, p 51.)

These changes mean that nurse educators will have to address even further the needs of the adult learner. More programs will be needed that permit part-time study and allow students to work while attending school. One option may be for more night or weekend course offerings. There will continue to be a need for emphasis on remedial education such as developmental courses in math, English, and English as a second language. The diversity in the student population means diversity in learning rates, which may be addressed with more self-paced learning modules (Fig. 7.4).

Educational Mobility

Educational mobility will also need to be addressed further. A growing number of individuals in health care are seeking more education. The issue is not one of entry into practice but rather of how to best facilitate the return of these individuals to nursing school for educational advancement that fits their professional and personal needs. The growth of web-based (online) courses may facilitate educational mobility.

A Shortage of Registered Nurses

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA, 2014), there are approximately 2.9 million nurses employed in 2012, and it is projected that the number will increase to 3.8 million by 2025, which is a 33% increase nationally. Although these projections indicate that there will not be a nursing shortage nationwide, it is predicted that 16 states (10 states in the west, 4 in the south, and 2 in the northeast) will still be experiencing a nursing shortage. Even though these projections seem very positive, factors such as early retirement or increased demand may nullify any positive gains.

A Shortage of Qualified Nursing Faculty

Data on the nursing faculty shortage reported by the AACN in their 2015-2016 Salaries of Instructional and Administrative Nursing Faculty in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs in Nursing (2016) indicate that the “average ages of doctorally prepared faculty holding the ranks of professor, associate professor, and assistant professor were 62, 57, and 51 years, respectively.” There are fewer nurses entering the profession who are choosing a teaching role. Because of decreased numbers of new teachers, along with the number of current faculty retiring, the number of qualified faculty will continue to decline.

The ability to earn more in the clinical and private sector is also attracting potential nurse educators to leave academia (AACN, 2015e). The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) gives the average salary of a nurse practitioner as $91,310, whereas the AACN reported that master’s-prepared faculty had an annual income of $73,633. In addition, the shortage of nursing faculty was the primary reason that 13,444 qualified master’s program applicants and 1844 qualified doctoral program applicants were not accepted into their respective graduate programs (AACN, 2014c).

Technology and Education

Educational learning will continue to change with advances in telecommunication and technology. Nurses and nurse educators will need education to implement these advances into the curriculum and into nursing practice. Cable television, the Internet, computer tablets, and smartphones have significantly extended the boundaries of the classroom; these technologies will facilitate the offering of courses to meet the lifestyle of the changing student population.

Changing Health Care Settings

There has been a major shift from inpatient to outpatient nursing services as health care and nursing focus on maintaining health rather than handling illness. However, with an increase in the age of the population, more inpatients have multiple chronic health problems. Society is now developing a variety of new health care settings. Are nurses educated for these new roles? What will the role of the advanced nurse practitioner be? Will there be enough nurses educationally prepared to meet these new challenges?

The Aging Population

There is a growing aging population. According to the Administration on Aging (2014), by 2040 there will be about 82.3 million older persons, over twice their number in 2000. The population age 65 and over has increased from 35.9 million in 2003 to 44.7 million in 2013 (a 24.7% increase) in just 10 years and is projected to more than double to 98 million by 2060. Currently, the older adult population represents 14.1% of the U.S. population, which is about one in every seven Americans. The 85+ population is projected to triple from 6 million in 2013 to 14.6 million in 2040. This is more than twice the number in 2000. Naisbitt and Aburdene stated in their book Megatrends 2000, published in 1991, “If business and society can master the challenge of daycare, we will be one step closer to confronting the next great care giving task of the 1990s—eldercare” (p 83). This is still a critical issue in the 21st century. In 2010, it was reported that the United States had well over 4600 adult daycare centers (35% increase since 2002), with a current estimate of more than 5000 currently operating (MetLife, 2010). Nursing educators need to address the provision of health care to the elderly and include it in the curricula.

Conclusion

The future of nursing looks bright and exciting. With the inception of the Affordable Care Act, technological advances, changes in health care settings, and increased demand for the services of the RN, nurses now have increased opportunities to chart their own destinies.

Nurses who have career plans and career goals will see the future trends in health care as a challenge and an opportunity for growth in roles such as case manager, independent consultant, nurse practitioner, nursing educator, nursing informatics, policy maker, and entrepreneur. In contrast, nurses without career goals may find themselves displaced or obsolete. There has never been a more exciting time to be entering the profession of nursing than right now. Opportunities in nursing are wide open to those with the sensitivity and the creativity to embrace the future.

I challenge you to get out a piece of paper and put your educational goals down in writing. After you do this, set some deadlines for when you want to achieve these goals. Place this piece of paper in a prominent place where you will see it every day.

What’s talked about is a dream,

What’s envisioned is exciting,

What’s planned becomes possible,

What’s scheduled is real.

Anthony Robbins