CHAPTER 32 Nose, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

The nose is the first part of the upper respiratory tract, and is responsible for warming, humidifying, and, to some extent, filtering inspired air. It also houses the olfactory epithelium which contains olfactory receptor neurones responsible for detecting airborne odorant molecules.

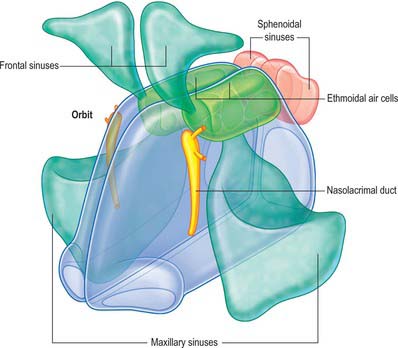

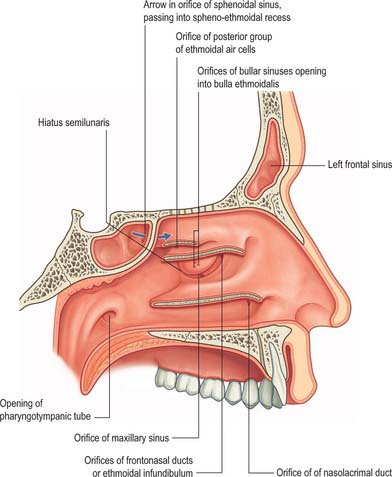

The nose may be subdivided into an external nose, which opens anteriorly onto the face through the nostrils or nares, and an internal chamber, divided sagittally by a septum into right and left cavities which open posteriorly into the nasopharynx through the posterior nasal apertures or choanae. The nasal cavities are housed in a supporting framework composed of bone and fibro-elastic cartilages. The larger bones in this framework contain air-filled spaces lined with respiratory epithelium, described collectively as the paranasal sinuses. The sinuses and the nasolacrimal ducts drain into the nasal cavity via openings in its lateral walls (Fig. 32.1).

EXTERNAL NOSE

BONE AND CARTILAGE

Bony skeleton of the external nose

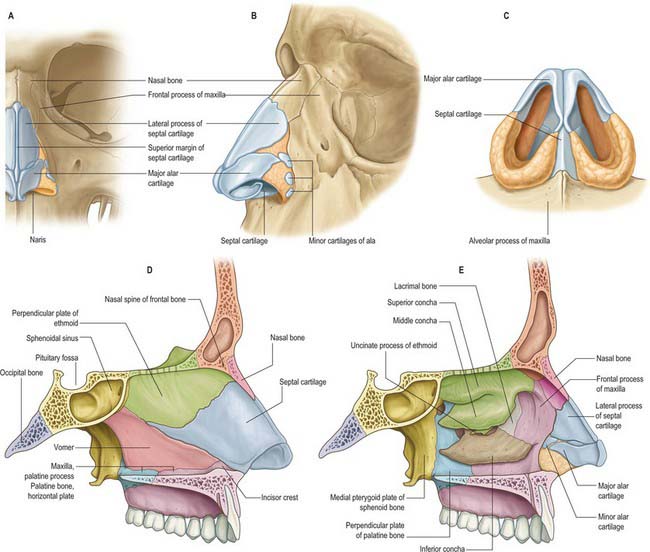

The piriform aperture has sharp edges. It is bounded below and laterally by the maxilla and above by the nasal bones (Fig. 32.2). The lateral part of the inferior edge of the piriform aperture merges into its lateral wall, which is formed by the frontal process of the maxilla. It is bounded above by the nasal part of the frontal bone and superomedially by the lateral edge of the nasal bone. The bony nasal septum articulates with the undersurface of the nasal bones and provides support to the dorsum of the nose. The nasal bones vary in thickness and width, which is of significance in planning osteotomies. They are thick and widest at the nasofrontal suture, narrow at the nasofrontal angle before they widen, and become thinner 9–12 mm below the nasofrontal angle.

Cartilaginous skeleton of the external nose

The cartilaginous framework consists of the paired lateral and major cartilages and several minor alar nasal cartilages (Fig. 32.2).

Major alar cartilage

The major alar cartilage is a thin flexible plate. It lies below the upper lateral cartilage and curves acutely around the anterior part of its naris. The medial part, the narrow medial crus (septal process), is loosely connected by fibrous tissue to its contralateral counterpart and to the anteroinferior part of the septal cartilage. The intermediate crus forms the margin of the apex of the nostril. The lateral crus lies lateral to the naris and runs superolaterally away from the margin of the nasal ala. The upper border of the lateral crus of the major alar cartilage is attached by fibrous tissue to the lower border of the lateral nasal cartilage. Its lateral border is connected to the frontal process of the maxilla by a tough fibrous membrane containing three or four minor alar cartilages. The junction between the lateral crura of the major alar and lateral cartilages is variable: the two edges may abut or overlap, in which case the lateral crus is then the more lateral at the junction. The lateral crus of the major alar cartilage is shorter than the lateral margin of the naris and runs away from the margin of the ala nasi. The lateral part of the margin of the ala nasi is fibroadipose tissue covered by skin. In front, the angulations or ‘domes’ between the medial and lateral crurae of the major alar cartilages are separated by a notch palpable at the tip of the nose.

MUSCLES

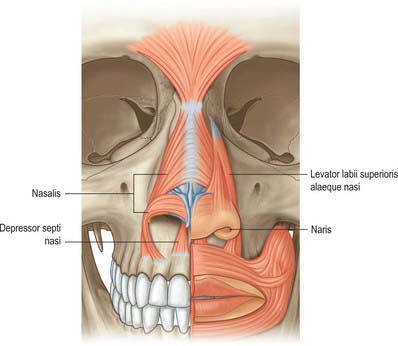

The nasal muscle group includes procerus, nasalis, dilator naris anterior, depressor septi and levator labii superioris alaequae nasi (Fig. 32.3). These muscles are involved in respiration, facial expression and in the production of some sounds during speech, when their activity is dependent upon the activity of orbicularis oris and the type of sound (see Clark et al 1998). Any or all of these muscles may be absent in cleft lip deformities with corresponding functional and aesthetic consequences.

Procerus

Procerus is a small pyramidal muscle that lies close to, and is often partially blended with, the medial side of the frontal part of occipitofrontalis. It arises from a fascial aponeurosis attached to the periosteum covering the lower part of the nasal bone, the perichondrium covering the upper part of the lateral nasal cartilage and the aponeurosis of the transverse part of nasalis. It is inserted into the glabellar skin over the lower part of the forehead between the eyebrows.

CUTANEOUS VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Nasal skin receives its blood supply from branches of the facial, ophthalmic and infraorbital arteries. The alae and lower part of the nasal septum are supplied by lateral nasal and septal branches of the facial artery and the lateral aspects and dorsum of the nose are supplied by the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic artery and the infraorbital branch of the maxillary artery. The venous networks draining the external nose do not run parallel to the arteries but correspond to arteriovenous territories of the face. The frontomedian region of the face, including the nose, drains to the facial vein, and the orbitopalpebral area of the face, including the root of the nose, drains to the ophthalmic veins. The connections of the veins of the nose, upper lip and cheek with the drainage area of the ophthalmic veins are clinically significant because they can be the route which spreads infection and initiates thrombosis of the major intracranial sinuses. Lymph drainage is primarily to the submandibular group of nodes although lymph draining from the root of the nose drains to superficial parotid nodes. There is experimental evidence that nasal lymphatics might play a major role in CSF transport in animals such as the sheep: there is currently very little evidence that a similar pathway exists in humans (but see Johnston et al 2004).

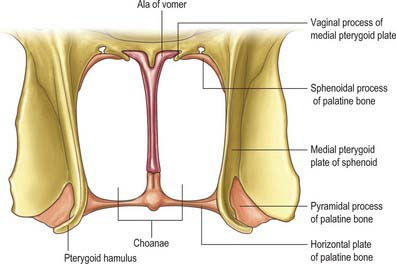

NASAL CAVITY

The nasal cavity communicates with the frontal, ethmoidal, maxillary and sphenoidal paranasal sinuses and opens into the nasopharynx through a pair of oval openings, the posterior nasal apertures or choanae. The latter are separated by the posterior border of the vomer, and each is limited above by the vaginal process of the medial pterygoid plates, laterally by the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone and the medial pterygoid plate, and below by the horizontal plate of the palatine bone (Fig. 32.4). The adult choana typically measures 2.5 cm in vertical height and 1.3 cm transversely: size is not usually affected by deviations of the nasal septum. The vomerovaginal and palatovaginal canals are found in the roof of this region.

Each half of the nasal cavity has a roof, floor, medial (septal) and lateral walls and a vestibule.

ROOF

The roof is horizontal in its central part and slopes downwards in front and behind (Fig. 32.3). The anterior slope is formed by the nasal spine of the frontal bones and by the nasal bones. The central region is formed by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone which separates the nasal cavity from the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. It contains numerous small perforations which transmit the olfactory nerves and their ensheathing meningeal layers, and a separate anterior foramen which transmits the anterior ethmoidal nerve and vessels. The posterior slope is formed by the anterior aspect of the body of the sphenoid, interrupted on each side by an opening of a sphenoidal sinus, and the sphenoidal conchae or superior conchae.

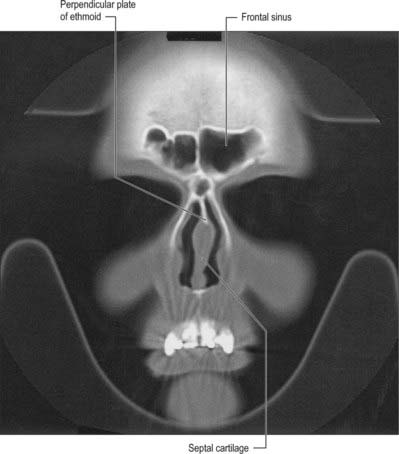

MEDIAL WALL

The medial wall of each nasal cavity is the nasal septum, a thin sheet of bone (posteriorly) and cartilage (anteriorly), that lies between the roof and floor of the cavity (Fig. 32.2D).

Bony septum

The septum is usually relatively featureless but sometimes exhibits ridges or bony spurs. The posterosuperior part of the septum and its posterior border are formed by the vomer, which extends from the body of the sphenoid to the hard palate (for more details, see Chapter 29). Its surface is grooved by the nasopalatine nerves and vessels. The anterosuperior part of the septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid which is continuous above with the cribriform plate. Other bones which make minor contributions to the septum at the upper and lower limits of the medial wall are the nasal bones and the nasal spine of the frontal bones (anterosuperior), the rostrum and crest of the sphenoid (posterosuperior), and the nasal crests of the maxilla and palatine bones (inferior).

Cartilaginous septum

Vomeronasal organ

In most amphibia, reptiles and mammals, the vomeronasal organ is the peripheral sensory organ of the accessory olfactory system. In these animals, paired vomeronasal organs are located either at the base of the nasal septum or in the roof of the mouth, and are involved in chemical communication that often, but not exclusively, is mediated via pheromones. In many macrosomatic animals the vomeronasal organ consists of a vomeronasal duct which contains chemosensory cells, and a vomeronasal nerve which terminates in the accessory olfactory bulb in the CNS. Whether adult humans possess a vomeronasal organ remains controversial; it is claimed that the duct sometimes persists beyond the embryonic stage (for detailed reviews, see Meredith 2001, Witt & Hummel 2006) but no neural connection appears to be present in humans after birth.

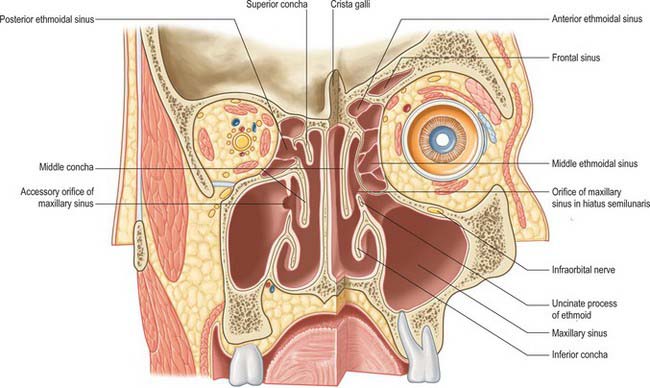

LATERAL WALL

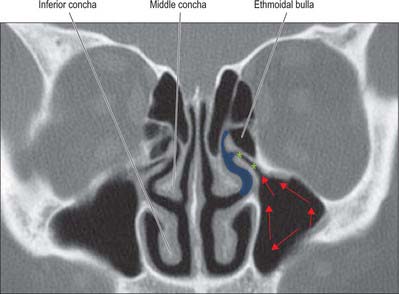

The lateral wall of the nasal cavity is formed anteroinferiorly by the maxilla and its anterior and posterior fontanelles (bony deficiencies in the medial wall of the maxilla which are obliterated to varying degrees by fibrous tissue); posteriorly by the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone; and superiorly by the labyrinth of the ethmoid bone. It contains three projections of variable size, the inferior, middle and superior nasal conchae (turbinates) (Figs 32.2E, 32.5). The conchae curve generally inferomedially, each roofing a groove, or meatus, which is open to the nasal cavity. The middle conchae may also curve inferolaterally, or may be expanded by an enclosed air cell to form a so called ‘concha bullosa’ (30% of individuals) or have a concave medial surface, known as a paradoxical turbinate (10% of individuals).

Inferior concha and inferior meatus

The inferior concha is a thin, curved, independent bone (for more details, see Chapter 29). It articulates with the nasal surface of the maxilla and the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone. Its free lower border is gently curved and the subjacent inferior meatus reaches the nasal floor. The inferior meatus is the largest meatus, and it extends along almost all of the lateral nasal wall. It is deepest at the junction of its anterior and middle thirds, where it admits the inferior opening of the nasolacrimal canal (see Ch. 39). The canal is formed by the articulations between the lacrimal groove of the maxilla, the descending process of the lacrimal bone and the lacrimal process of the inferior concha. During postnatal development, the ostium of the nasolacrimal duct moves upwards and is increasingly hidden under the over-arching inferior concha.

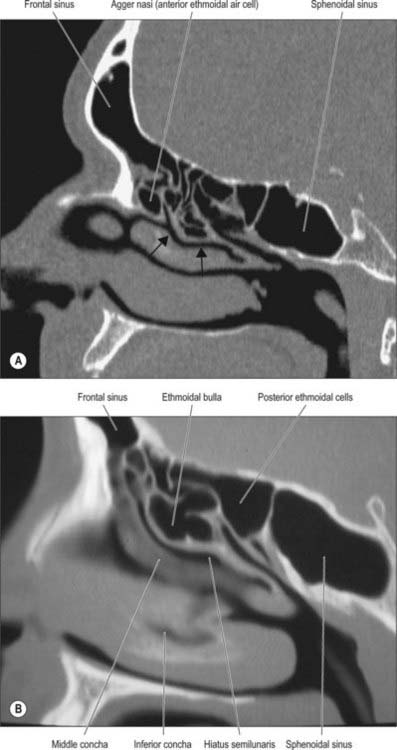

Middle concha and middle meatus

The middle concha is a medial process of the ethmoidal labyrinth and may be pneumatized (conchal sinus). It extends back to articulate with the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone. The region beneath it is the middle meatus, which is deeper in front than behind, lies below and lateral to the middle concha, and continues anteriorly into a shallow fossa above the vestibule, termed the atrium of the middle meatus.

The main features of the lateral nasal wall are a rounded elevation, the bulla ethmoidalis, and a curved cleft, the hiatus semilunaris, formed by the posterior edge of the uncinate process, which constitutes the medial limit of the ethmoid infundibulum, a slit-like space that leads towards the maxillary ostium. The maxillary ostium is normally found lateral to the antero-inferior aspect of the uncinate process. The latter can be attached to the lateral nasal wall (50%), the anterior cranial fossa (25%) or the middle concha (25%). Where the uncinate process is attached determines whether the frontal sinus drains lateral to the ethmoid infundibulum or into it; if the uncinate process is attached to the lateral wall, the frontal sinus will drain into the middle meatus and not into the ethmoid infundibulum, but with the other configurations the sinus will drain into the infundibulum, and thus near or into the maxillary ostium. Agger nasi air cells are the name given to anterior ethmoid air cells that lie anterior to the ethmoid bulla (Fig. 32.5; see Fig. 32.12). The posterior fontanelle lies posterior to the uncinate process where there is no bone in the medial wall of the maxillary sinus, inferoposterior to the hiatus; it frequently has an accessory opening.

Fig. 32.12 Coronal CT scan showing the sphenoidal air sinus. S, Sphenoid sinus; C, Posterior choanae.

Sphenopalatine foramen

The sphenopalatine foramen, which is really a fissure, can be approached surgically through the middle meatus. It is posterior to the middle meatus and transmits the sphenopalatine artery and nasopalatine and superior nasal nerves from the pterygopalatine fossa (see Ch. 31). It is bounded above by the body and concha of the sphenoid, below by the superior border of the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, and in front and behind by the orbital and sphenoidal processes of the palatine bone respectively.

NASAL AND OLFACTORY MUCOSAE

Nasal mucosa

The mucosa is thickest and most vascular over the conchae, especially at their extremities, and also on the anterior and posterior parts of the nasal septum and between the conchae. The mucosa is very thin in the meati, on the nasal floor and in the paranasal sinuses. Its thickness reduces the volume of the nasal cavity and its apertures significantly. The lamina propria contains cavernous vascular tissue with large venous sinusoids.

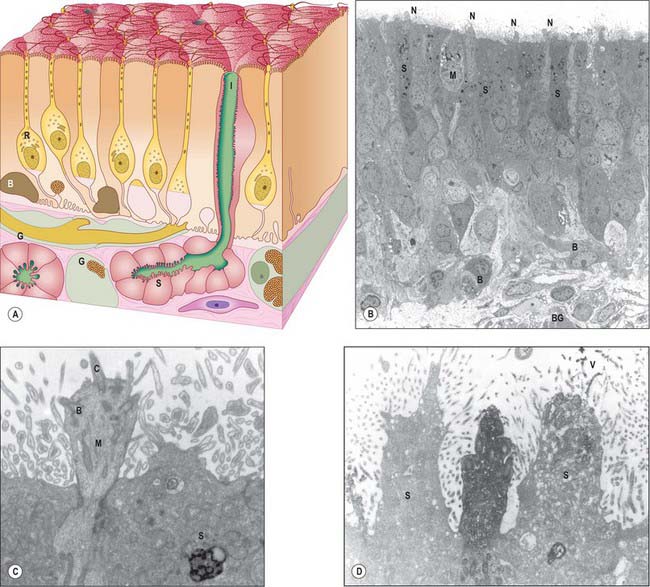

Olfactory mucosa

Olfactory mucosa (Fig. 32.6) covers approximately 5 cm2 of the posterior upper parts of the lateral nasal wall, including the upper part of the vertical portion of the middle concha (where it is interspersed with respiratory epithelium in a checkerboard fashion) and the opposite part of the nasal septum, the superior concha, the sphenoethmoidal recess, the upper part of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and the portion of the roof of the nose that arches between the septum and lateral wall, including the underside of the cribriform plate (constituting the olfactory cleft or groove). It consists of a yellowish brown pigmented pseudostratified epithelium, containing olfactory receptor neurones, sustentacular cells and two classes of basal cell, lying on a subepithelial lamina propria containing subepithelial olfactory glands (of Bowman) and bundles of axons derived from the olfactory receptor neurones which course through the mucosa on their way to the cribriform plate. The glands secrete a predominantly serous fluid through ducts which open onto the epithelial surface. These secretions form a thin fluid layer in which sensory cilia and the microvilli of the sustentacular cells are embedded.

Olfactory receptor neurones are bipolar. Their cell bodies and nuclei are located in the middle zone of the olfactory epithelium. Each neurone has a single unbranched apical dendrite, 2 μm diameter, which extends to the epithelial surface, and a basally directed unmyelinated axon, 0.2 μm diameter, which passes in the opposite direction, penetrates the basal lamina and enters the lamina propria. The tips of the dendrites project into the overlying secretory fluid and are expanded into characteristic endings (knobs) (Fig. 32.6B). Groups of up to 20 cilia radiate from the circumference of each ending and extend for long distances parallel to the epithelial surface. Internally, the short proximal part of each cilium has the ‘9 + 2′ pattern of microtubules typical of motile cilia, while the longer distal trailing end contains only the central pair of microtubules. The olfactory cilia lack dynein arms and are thought to be non-motile; their primary purpose is to increase the surface area of sensory receptor membrane available for the efficient detection of odorant molecules transferred across the mucous layer by odorant binding proteins. Mature olfactory neurones express olfactory marker protein (OMP), an abundant cytoplasmic protein involved in olfactory signal transduction (Fig. 32.6D). Each olfactory receptor neurone expresses receptors for a single (or very few) odorant molecules. In humans, over 1000 genes code for functional odorant receptors; the number of functional genes is much higher in macrosmotic animals (Buck & Axel 1991). Although neurones with the same receptor specificity are randomly distributed within anatomical zones of the epithelium, their axons all converge on the same glomerulus in the olfactory bulb. Specific odours activate a unique spectrum of receptor neurones which in turn activate restricted groups of glomeruli and their second order neurones.

Microvillar cells occupy a superficial position in the olfactory epithelium. They are flask-shaped and electron-lucent, and the apical end of each cell gives rise to a tuft of microvilli that project into the mucus layer lining the nasal cavity (Fig. 32.6B). Cell counts in longitudinal sections reveal that microvillar cells occur with a density that is approximately one tenth of the density of ciliated olfactory neurones: their function and origin has yet to be determined.

Sustentacular, or supporting, cells are columnar cells that separate and partially ensheathe the olfactory receptor neurones. Their large nuclei form a layer superficial to the neuronal nuclei within the epithelium. The cells are capped by numerous long, irregular, microvilli which lie in the secretory fluid layer that covers the surface of the epithelium, intermingled with the trailing ends of the cilia on the olfactory receptor endings. Their expanded bases contain numerous lamellated dense bodies, which are the remnants of secondary lysosomes, and which contribute significantly to the pigmentation of the olfactory area (Fig. 32.6B,C). The granules gradually accumulate with age, and because these cells are long-lived, the intensity of pigmentation also increases with age. Neighbouring sustentacular cells are linked by desmosomes close to the epithelial surface, an arrangement that helps to stabilize the epithelium mechanically. Sustentacular cells and olfactory receptor neurones are linked by tight junctions at the level of the epithelial surface.

Turnover of olfactory receptor neurones

Olfactory receptor neurones are lost and replaced throughout life. Individual receptor cells have a variable lifespan, thought to average 1–3 months. Stem cells situated near the base of the epithelium undergo periodic mitotic division throughout life, giving rise to new olfactory receptor neurones which then grow a dendrite to the olfactory surface and an axon to the olfactory bulb. The cell bodies of these new receptor neurones gradually move apically until they reach the region just below the supporting cell nuclei. When they degenerate, dead neurones are either shed from the epithelium or are phagocytosed by sustentacular cells. The rate of receptor cell loss and replacement increases after exposure to damaging stimuli, but declines slowly with age, a phenomenon that presumably contributes to diminishing olfactory sensory function in old age. Biopsy specimens from normosmic adults have revealed that patchy replacement of olfactory with respiratory epithelium occurs even in young healthy adults (Paik et al 1992, Holbrook et al 2005).

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE OF THE NASAL CAVITY

Many of the vessels and nerves supplying the nasal cavities arise within the pterygopalatine fossa and these origins are described in Chapter 31.

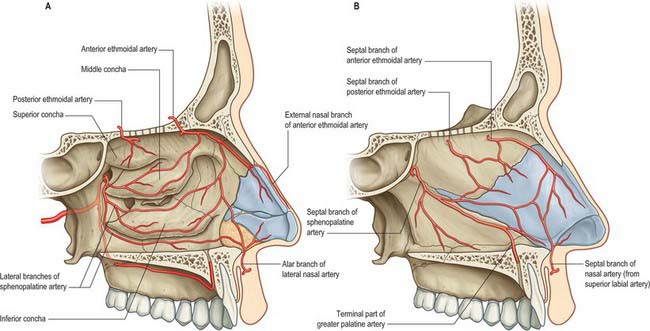

Arteries

Branches of the ophthalmic, maxillary and facial arteries supply different territories within the walls, floor and roof of the nose (Fig. 32.7A,B). They ramify to form anastomotic plexuses within and deep to the nasal mucosa. Anastomoses also occur between some larger arterial branches. The anterior and posterior ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic artery supply the ethmoidal and frontal sinuses and the roof of the nose (including the septum). The anterior ethmoidal artery usually runs within the bone of the anterior skull base unless this is well pneumatized with a supraorbital cell, in which case the artery is more likely to be positioned away from the skull base and to be more prone to surgical damage. The sphenopalatine branch of the maxillary artery supplies the mucosa of the conchae, meati and posteroinferior part of the nasal septum, i.e. it is the principal vessel supplying the nasal mucosa. The artery comes out of a fissure (erroneously termed a foramen), and normally divides before it enters the nasal cavity behind the crista ethmoidalis. The number and distribution of its branches show great variation. The greater palatine branch of the maxillary artery supplies the region of the inferior meatus. Its terminal part ascends through the incisive canal to anastomose on the septum with branches of the sphenopalatine and anterior ethmoidal arteries and with the septal branch of the superior labial artery. This septal region (Little’s area) is a common site of bleeding from the nose. The infraorbital artery and the superior, anterior, and posterior alveolar branches of the maxillary artery supply the mucosa of the maxillary sinus. The pharyngeal branch of the maxillary artery supplies the sphenoidal sinus.

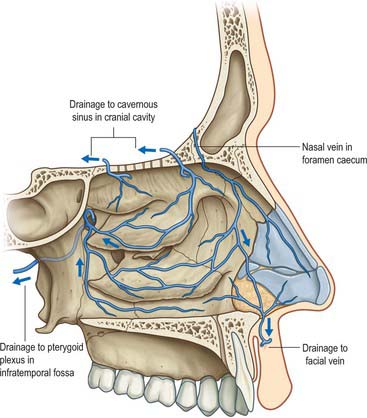

Veins

A rich submucosal cavernous plexus is especially dense in the posterior part of the septum and in the middle and inferior conchae (Fig. 32.8). Numerous arteriovenous anastomoses are present in the deep layer of the mucosa and around the mucosal glands. The cavernous conchal plexuses resemble those in erectile tissue: the nasal cavity is susceptible to blockage should they become engorged. Veins from the posterior part of the nose generally pass to the sphenopalatine vein that runs back through the sphenopalatine foramen to drain into the pterygoid venous plexus. The anterior part of the nose is drained mainly through veins accompanying the anterior ethmoidal arteries, and these veins subsequently pass into the ophthalmic or facial veins. A few veins pass through the cribriform plate to connect with those on the orbital surface of the frontal lobes of the brain. When the foramen caecum is patent, it transmits a vein from the nasal cavity to the superior sagittal sinus.

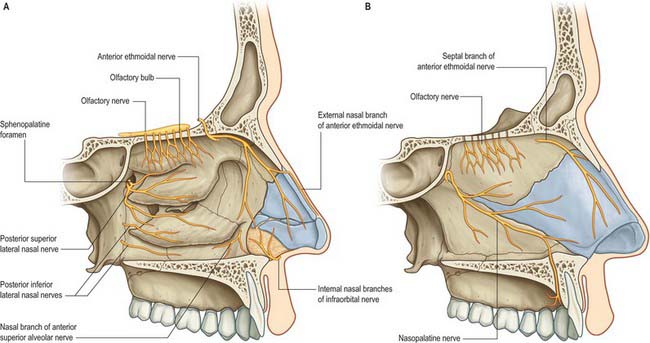

INNERVATION OF THE NASAL CAVITY

Olfaction is mediated via the olfactory nerves. General sensation (touch, pain and temperature) from the nasal mucosa is carried by branches of the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerves (Fig. 32.9). Trigeminal fibres close to, and within, the epithelial layer are sensitive to noxious chemicals, e.g. ammonia and sulphur dioxide. Autonomic fibres innervate mucous glands and control cyclical and reactive vasomotor activity.

Trigeminal innervation

The anterior ethmoidal branch of the nasociliary nerve leaves the cranial cavity through a small slit near the crista galli and enters the roof of the nasal cavity where it runs in a groove on the inner surface of the nasal bone, supplying the roof of the nasal cavity. It gives off a lateral internal branch to supply the anterior part of the lateral wall and a medial internal branch to the anterior and upper parts of the septum, before emerging at the inferior margin of the nasal bone as the external nasal nerve to supply the skin of the external nose to the nasal tip. The infraorbital nerve supplies the nasal vestibule. The anterior superior alveolar nerve supplies part of the septum, the floor near the anterior nasal spine and the anterior part of the lateral wall as high as the opening of the maxillary sinus; the lateral posterior superior nasal and the posterior inferior nasal branches of the greater palatine nerve together supply the posterior three-quarters of the lateral wall, roof and floor; the medial posterior superior nasal nerves and the nasopalatine nerve supply the inferior part of the nasal septum; and branches from the nerve of the pterygoid canal supply the upper and posterior part of the roof and septum.

NASAL AIRFLOW AND THE NASAL CYCLE

Airflow dynamics are recognized as playing a key role in conditioning (i.e. warming, humidifying and filtering) inspired air, however these dynamics are still poorly understood (Churchill et al 2004, Boyce & Eccles 2006). It is generally agreed that airflow within the nose is both laminar and turbulent. Inspired air is forced to pass through the nasal valve, and then expands as it passes further into the nasal cavity which offers little airflow resistance. This sudden change in speed and pressure produces turbulence and eddies. These currents allow adequate contact of inspired air with respiratory epithelium and facilitate odorant transport to the olfactory area. Chewing also affects nasal airflow: pulses of aroma-laden air are pumped out of the mouth into the retronasal region with each chew.

Disturbances of the normal airflow pattern, whether produced by mucocutaneous or skeletal changes within the nose, affect normal nasal breathing and are usually perceived as some form of nasal obstruction.

PARANASAL SINUSES

The paranasal sinuses are the frontal, ethmoidal, sphenoidal and maxillary sinuses, housed within the bones of the same name (Figs 32.1, 32.10–32.13). They all open into the lateral wall of the nasal cavity by small apertures that permit both the equilibration of air between the various air spaces and the clearance of mucus from the sinuses into the nose via a mucociliary escalator. The detailed position of these apertures, and the precise form and size of each of the sinuses, varies enormously between individuals. Respiratory epithelium extends through the apertures of the paranasal sinuses to line their cavities, a feature that unfortunately favours the spread of infections. Sinus mucosa is thinner, less vascular and has fewer goblet cells than nasal mucosa. Cilia are always present in the mucosa near the apertures but less evenly distributed elsewhere within the sinuses.

FRONTAL SINUS

The paired frontal sinuses are posterior to the superciliary arches, between the outer and inner tables of the frontal bone (Figs 32.10, 32.11, 32.13A). Each usually underlies a triangular area on the surface of the face, its angles formed by the nasion, a point 3 cm above the nasion and the junction of the medial one-third and lateral two-thirds of the supraorbital margin. The two sinuses are rarely symmetrical, since the septum between them usually deviates from the median plane. Each sinus may be further divided into a number of communicating recesses by incomplete bony septa.

The aperture of each frontal sinus either opens into the anterior part of the corresponding middle meatus by the ethmoidal infundibulum either as a frontonasal recess (rather than a duct) or medial to the hiatus semilunaris if the uncinate process is attached to the lateral nasal wall or an agger nasi cell.

The frontal sinuses are rudimentary or absent at birth, generally well developed between the seventh and eighth years, but reach full size only after puberty. They are more prominent in males, and lend the forehead an obliquity that contrasts with the vertical or convex profile typical of children and females. In the presence of a persistent metopic suture, the frontal sinuses develop separately on either side of the suture, which can be helpful in excluding frontal fractures. (The frontal bone is described in Chapter 29.)

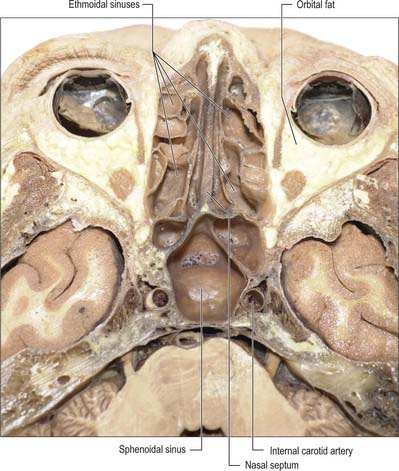

SPHENOIDAL SINUS

The sphenoidal sinuses are two large irregular cavities within the body of the sphenoid and therefore lie posterior to the upper part of the nasal cavity (Figs 32.12–32.15). Each opens into the corresponding sphenoethmoidal recess via an aperture high on the anterior wall of the sinus. At birth the sinuses are minute cavities, and their main development occurs after puberty. The average adult dimensions are: vertical height 2 cm; transverse breadth 1.8 cm; anteroposterior depth 2.1 cm. The sinuses are usually separated by a septum that deviates from the midline in 75%, so that they are unequal in size and form. Their lumina may be further partially divided by bony laminae, accessory septa, especially in the region of former synchondroses. Occasionally one sinus overlaps the other above and, rarely, they intercommunicate. Bony ridges, produced by the internal carotid artery, pterygoid canal, maxillary branch of trigeminal and, in 15% of individuals, the optic nerve, may project into the sinuses from their lateral walls. Dehiscences in the osseous walls of either sinus may occasionally leave their mucosa in contact with the overlying dura mater.

Fig. 32.15 Horizontal section of the head showing the ethmoidal and sphenoidal sinuses.

(By permission from Berkovitz BKB, Moxham BJ 2002 Head and Neck Anatomy. London: Martin Dunitz.)

The extent of pneumatization of surrounding bone is highly variable. In nearly 50% of skulls, a lateral recess may extend into the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid or the pterygoid processes, and may even invade the basilar part of the occipital bone almost to the foramen magnum. A posterior ethmoidal sinus may extend posterosuperior to the relatively smaller sphenoidal sinuses. The sphenoidal sinuses are related above to the optic chiasma and hypophysis cerebri and on each side to the internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus (see Ch. 27). One or both sinuses may partially encircle the optic canal.

ETHMOIDAL SINUSES

The ethmoidal sinuses differ from the other paranasal sinuses in that they are formed of multiple thin-walled cavities in the ethmoidal labyrinth (Figs 32.10, 32.13–32.15) (for more details, see Chapter 29). The number and size of the cavities varies, from three large to 18 small sinuses on each side. They lie between the upper part of the nasal cavity and the orbit, and are separated from the latter by the paper-thin lamina papyracea or orbital plate of the ethmoid (this presents a poor barrier to infection which may therefore spread into the orbit). Pneumatization may extend into the middle concha, or into the body and wings of the sphenoid bone lateral to the sphenoid sinus.

MAXILLARY SINUS

The maxillary sinus (maxillary antrum), is the largest of the paranasal sinuses. It fills the body of the maxilla (Chapter 29) and is pyramidal in shape (Fig. 32.10, Fig. 32.14). The base is medial and forms much of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. The floor, which often lies below the nasal floor, is formed by the alveolar process and part of the palatine process of the maxilla. It is related to the roots of the teeth, especially the second premolar and first molar, but may extend posteriorly to the third molar tooth and/or anteriorly to incorporate the first premolar, and sometimes the canine. Defects in the bone overlying the roots are not uncommon. The roof of the sinus forms the major part of the floor of the orbit. It contains the infraorbital canal which may exhibit dehiscences. The lateral truncated apex of the pyramid extends into the zygomatic process of the maxilla, and may reach the zygomatic bone, in which case it forms the zygomatic recess which throws a V-shaped shadow over the antrum on a lateral radiograph.

The facial surface of the maxilla forms its anterior wall, and is grooved internally by a delicate canal (canalis sinuosus) which houses the anterior superior alveolar nerve and vessels as they pass forwards from the infraorbital canal. The posterior wall is formed by the infratemporal surface of the maxilla: it contains alveolar canals that may produce ridges in the sinus and that also conduct the posterior superior alveolar vessels and nerves to the molar teeth. The medial wall is deficient posterosuperiorly at the maxillary hiatus, a large opening which is partially closed in an articulated skull by portions of the perpendicular plate of the palatine bone, the uncinate process of the ethmoid bone, the inferior nasal concha, the lacrimal bone, and the overlying nasal mucosa, to form an ostium and anterior and posterior fontanelles. The ostium usually opens into the inferior part of the ethmoidal infundibulum, and thence into the middle meatus, via the hiatus semilunaris (the hiatus forms the area above the superior edge of the uncinate process). The fontanelles are covered only by periosteum and mucosa and may contain accessory ostia which may be visible on CT. All of the openings are nearer the roof than the floor of the sinus which means that the natural drainage of the maxillary sinus is reliant on an intact mucociliary escalator: the cilia of the sinus mucoperiosteum normally beat towards the ostium.

Ostiomeatal complex

The term ostiomeatal complex, or ostiomeatal unit, refers to the area that includes the maxillary sinus ostium, ethmoid infundibulum and the hiatus semilunaris (Fig. 32.14). It is the common pathway for drainage of secretions from the maxillary and anterior group of ethmoidal sinuses; where the uncinate process attaches to the lateral nasal wall the complex also drains the frontal sinus.

SPREAD OF INFECTION TO CRANIAL CAVITY

The state of health of the paranasal sinuses depends on immunity, mucociliary clearance and aeration of the sinuses. The middle meatus forms the common drainage pathway for the anterior ethmoidal, frontal and maxillary sinuses, and can be readily examined with a fibreoptic endoscope (Simmen & Jones 2005). The posterior ethmoidal and sphenoidal sinuses drain into the superior meatus and sphenoethmoidal recess. Endoscopic examination will usually show infected mucus draining from these areas. Maxillary sinus infection may also spread from infected teeth.

Boyce J, Eccles R. Do chronic changes in nasal airflow have any physiological or pathological effect on the nose and paranasal sinuses? A systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31:15-19.

Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175-187.

Churchill SE, Shackelford LL, Georgi JN, Black MT. Morphological variation and airflow dynamics in the human nose. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16:625-638.

Doig TN, McDonald SW, McGregor OA. Possible routes of spread of carcinoma of the maxillary sinus to the oral cavity. Clin Anat. 1998;11:149-156.

Emanuel JM. Epistaxis. Cummings CW, et al, editors. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd edn., vol. 2. St Louis: Mosby, 1998;852-865.

Describes the blood supply to the nose and the surgical approaches to control epistaxis..

Holbrook EH, Leopold DA, Schwob JE. Abnormalities of axon growth in human olfactory mucosa. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2144-2154.

Jafek BW. Ultrastructure of human nasal mucosa. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1576-1599.

Johnston M, Zakharov A, Papaiconomou C, Salmasi G, Armstrong D. Evidence of connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatic vessels in humans, non-human primates and other mammalian species. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2004;1:2.

Lang J. Clinical Anatomy of the Nose, Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. Stuttgart: Thième, 1989.

McGowan DA, Baxter PW, James J. The Maxillary Sinus. Oxford: Wright, 1993.

Meredith M. Human vomeronasal organ function: a critical review of best and worst cases. Chem Senses. 2001;26:433-445.

Navarro JAC. The Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses: Surgical Anatomy. Berlin: Springer, 1997.

Paik SI, Lehman MN, Seiden AM, Duncan HJ, Smith DV. Human olfactory biopsy. The influence of age and receptor distribution. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:731-738.

Simmen D, Jones N. Manual of endoscopic sinus surgery and its extended applications. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2005.

Stammberger H, Kennedy DW. Paranasal sinuses: anatomic terminology and nomenclature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104(Suppl 167):7-16. (10) Part 2

Traxler H, Windisch A, Geyerhofer U, Surd R, Solar P, Firbas W. Arterial blood supply of the maxillary sinus. Clin Anat. 1999;12:417-421.

Witt M, Hummel T. Vomeronasal versus olfactory epithelium: is there a cellular basis for human vomeronasal perception? Internat Rev Cytol. 2006;248:209-259.