Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

Anatomy and physiology

The nose

Anatomy

It is useful to consider the anatomy of the nose by dividing it into:

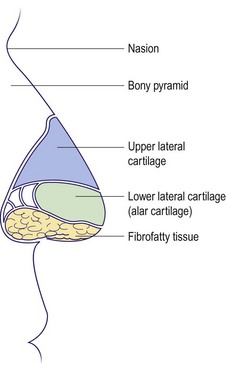

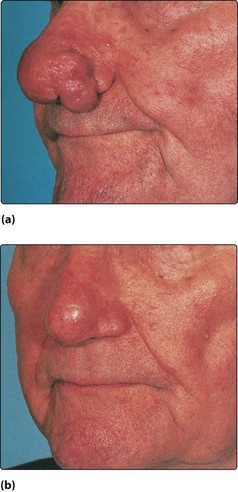

External nose

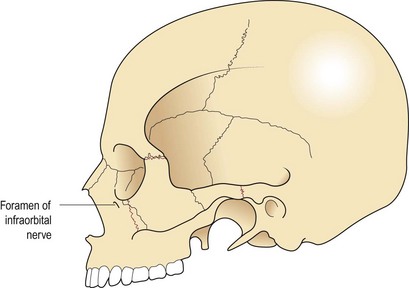

The upper third of the external nose (Fig. 2.1) is bony, consisting of nasal bones which connect with the nasion at the forehead. The inferior two-thirds are cartilaginous, consisting of the upper lateral and lower lateral (alar) cartilages. The tip laterally contains resilient but pliable fibrocartilage. This allows maintenance of nasal shape after minor trauma. The skin over the cartilaginous portion is closely adherent and contains multiple sebaceous glands; these latter structures may hypertrophy to form a rhinophyma.

Nasal cavity

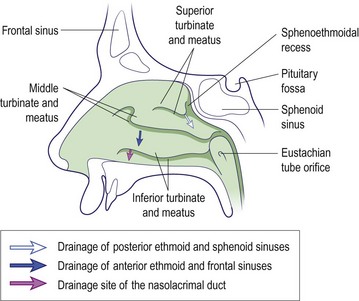

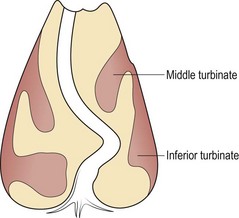

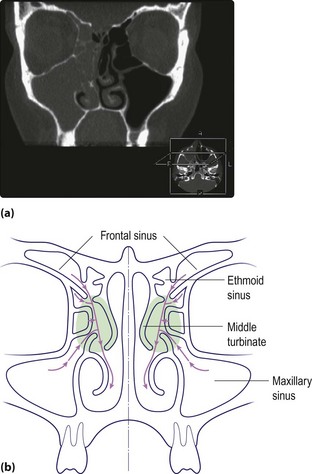

The nasal cavity stretches from the vestibule anteriorly to the nasopharynx posteriorly and is divided by a midline osteocartilaginous septum. The lateral wall of the cavity supports a series of ridges called turbinates (Fig. 2.2). These structures are lined by ciliated columnar epithelium and contain erectile tissue. The paranasal sinuses – maxillary, frontal, ethmoid and sphenoid – drain into the nasal cavity around the middle turbinate.

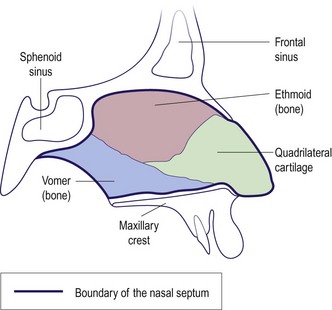

The nasal septum comprises bony and cartilaginous elements. Inferiorly, it is inserted into a groove in the maxillary crest (Fig. 2.3). It is lined with mucoperichondrium and mucoperiosteum over the cartilage and bone, respectively. The nasal septum is rarely straight; marked displacement causes nasal airway blockage and an external cosmetic deformity.

The paranasal sinuses

Anatomy

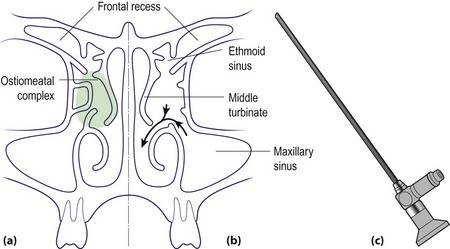

The paranasal sinuses (Fig. 2.4) are really extensions of the nasal cavity as air-filled spaces into the skull bones. Although paired anatomically, from a pathophysiological view they should be grouped as anterior and posterior. The frontal, anterior ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses (anterior group) drain into the middle meatus, and the posterior ethmoidal and sphenoid (posterior group) drain into the superior meatus and sphenoethmoidal recess. The crucial drainage area of the anterior group of paranasal sinuses is called the ostiomeatal complex (Fig. 2.4). The nasolacrimal duct opens into the anterior part of the inferior meatus.

Physiology

Anatomy and physiology

The nose is structurally composed of bone and cartilage.

The nose is structurally composed of bone and cartilage.

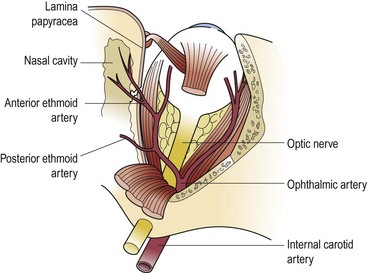

Both the external and internal carotid arteries provide the rich vascular supply of the nasal mucosa.

Both the external and internal carotid arteries provide the rich vascular supply of the nasal mucosa.

The nose has an important protective role in filtering, humidifying and warming inspired air.

The nose has an important protective role in filtering, humidifying and warming inspired air.

The nose, as part of the respiratory tract, is prone to acute infection and allergic phenomena.

The nose, as part of the respiratory tract, is prone to acute infection and allergic phenomena.

Since the paranasal sinuses drain via the nose, sinus disease is frequently due to primary problems in the nose.

Since the paranasal sinuses drain via the nose, sinus disease is frequently due to primary problems in the nose.

Symptoms, signs and investigations

Symptoms

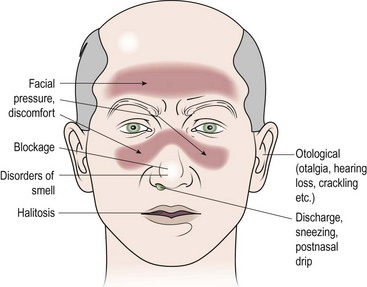

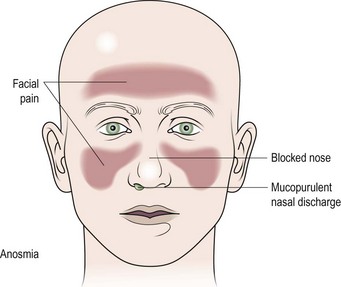

It is vital to establish the precise complaint of the patient; therefore, a full history is mandatory (Fig. 2.5).

Nasal obstruction

Nasal obstruction is the most common symptom, and may be due to anatomical abnormalities, disorders of the mucous membrane lining or stimulation of the autonomic nervous system (Table 2.1). An allergic aetiology is likely where the symptoms manifest after contact with allergens such as grass pollen, feathers or animal dander. Viral infections, e.g. acute coryza and influenza, cause severe nasal obstruction but generally resolve rapidly over days. An overactivity of the parasympathetic as compared to the sympathetic nerve supply will cause dilatation of the vascular tree and hence engorgement. This is particularly noted by some patients in stress situations and with alterations in ambient temperature and humidity. Neoplasia produces a progressive unilateral obstruction.

| Variety | Associated conditions |

|---|---|

| Anatomical | Septal deflection |

| Adenoidal hypertrophy | |

| Neoplasia | |

| Choanal atresia | |

| Disorders of nasal lining | Allergic and infective rhinitis |

| Nasal polyps | |

| Autonomic nervous system | Vasomotor rhinitis |

Nasal discharge

The specific character of the discharge is helpful in deciding aetiology (Table 2.2). Many patients describe this as ‘catarrh’. However, if it produces a runny nose, the discharge should be described as rhinorrhoea and the term ‘catarrh’ (or postnasal drip) reserved for nasal discharge passing backwards into the nasopharynx. Epistaxis is nasal haemorrhage and is most commonly due to spontaneous rupture of a blood vessel in the nasal mucous membrane. However, it is vital to exclude any bleeding disorders and neoplasms. If the discharge is offensive, it may indicate a bacterial infection, the presence of a foreign body or neoplasia.

Table 2.2 Nasal discharge: its characteristics and significance

| Character of discharge | Associated conditions |

|---|---|

| Watery/mucoid | Allergic, infective (viral) and vasomotor rhinitis |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | |

| Mucopurulent | Infective (bacterial) rhinitis and sinusitis |

| Foreign body | |

| Serosanguineous | Neoplasia |

| Bloody | Trauma, neoplasia, bleeding diathesis |

Signs

External

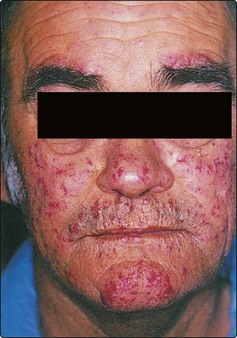

Certain cosmetic deformities such as angulation of the bony nasal pyramid or a nasal hump may be obvious. A saddle deformity due to previous injury or infection is readily identified. It is not unusual to find the septal cartilage dislocated into the nasal vestibule (Fig. 2.6).

Investigations

Allergy testing

The simplest allergy test is a skin-prick performed on the volar aspect of the forearm. A wide variety of allergens may be tested, but the common ones include pollens, animal dander, and house and dust mite. Controls such as a negative control (saline) and positive control (histamine) should be employed. A positive response produces a wheal and flare (in about 20 minutes) which can be graded. A negative response does not exclude allergy, and a positive response is not absolute proof that the specific allergen is causing symptoms (Fig. 2.8). The radioallergosorbent test (RAST) measures allergen-specific serum immunoglobulin E, but is expensive.

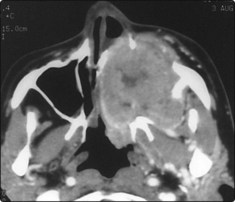

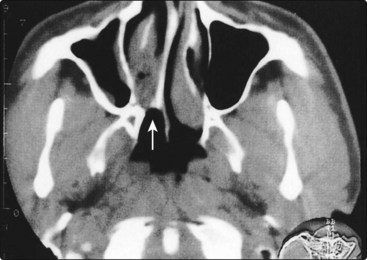

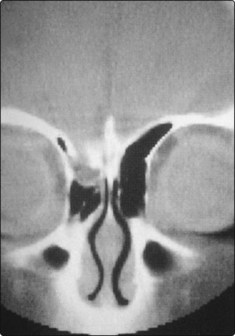

Radiology

Plain X-rays of the sinuses have limited value. Computed tomography (CT) is the imaging of choice for the majority of nasal and sinus disease (Fig. 2.9). Soft tissue abnormalities and tumours require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 2.10).

Miscellaneous

Symptoms, signs and investigations

Nasal obstruction is the most common symptom.

Nasal obstruction is the most common symptom.

The characteristics of nasal discharge may be suggestive of particular disease.

The characteristics of nasal discharge may be suggestive of particular disease.

Nasal pathology may, via the trigeminal nerve, give rise to referred head and neck pain.

Nasal pathology may, via the trigeminal nerve, give rise to referred head and neck pain.

The internal nose is best examined using a rigid endoscope.

The internal nose is best examined using a rigid endoscope.

Skin-prick tests for nasal allergy are recommended for investigating rhinitis.

Skin-prick tests for nasal allergy are recommended for investigating rhinitis.

CT and MRI have replaced plain radiology in the detailed examination of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

CT and MRI have replaced plain radiology in the detailed examination of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

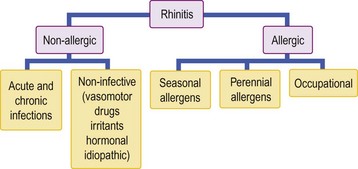

Allergic and vasomotor rhinitis

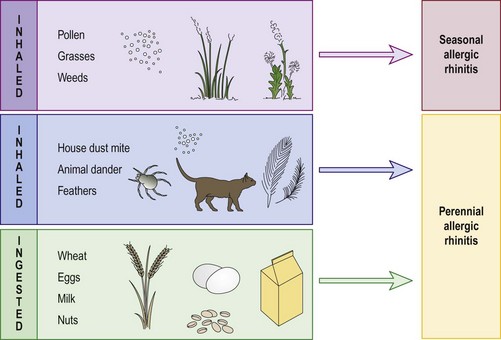

The term ‘rhinitis’ implies an inflammatory response of the lining membrane of the nose and may be intermittent or persistent. It is important to understand that such an event can occur as a consequence of both primary allergic and non-allergic mechanisms (Fig. 2.11). In allergic rhinitis, specific allergens are responsible for a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction, and the symptom complex may be subclassified as being predominantly seasonal or perennial. Non-allergic pathologies include viral and bacterial infections (pp. 38, 50), as well as autonomic nervous system abnormalities which can result in vasomotor rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis

More than 20% of the population in Western Europe suffers to some degree from nasal manifestations of an antigen–antibody type 1 hypersensitivity reaction (Fig. 2.12). In seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever), the allergens are inhaled, e.g. grass, pollens, weeds and flowers. Animal dander, house dust mite and feathers are the principal allergens in perennial allergic rhinitis and have no seasonal variation. Rarely, ingested allergens are implicated in the perennial group, e.g. dairy products and wheat. This would normally occur in conjunction with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Clinical features

The clinical features of allergic rhinitis include the classic triad of:

nasal obstruction due to mucosal vasodilatation and oedema

nasal obstruction due to mucosal vasodilatation and oedema

rhinorrhoea (runny nose) due to enhanced activity of glandular elements

rhinorrhoea (runny nose) due to enhanced activity of glandular elements

Typically, the nasal mucosa has a boggy, oedematous appearance (Fig. 2.13); it is covered by a thin layer of watery secretion. Application of a vasoconstrictor produces marked mucosal shrinking with improvement in the nasal airway. Skin-prick tests should be interpreted only in relation to the history. Negative skin tests in the face of obvious allergens are not infrequent.

Management

changing a feather pillow to foam

changing a feather pillow to foam

washing the bedclothes twice weekly, as the antigen is heat sensitive

washing the bedclothes twice weekly, as the antigen is heat sensitive

using a dust-proof cover over the mattress, duvet and pillows

using a dust-proof cover over the mattress, duvet and pillows

Rhinitis medicamentosa

Management

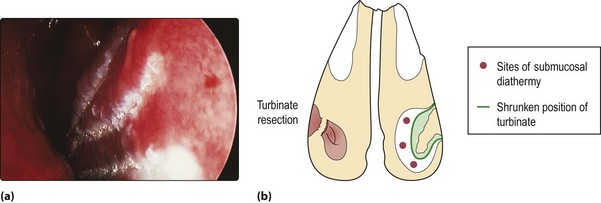

Treatment should be prophylactic, i.e. certain preparations should only be employed as ‘short, sharp’ therapies. Established rhinitis medicamentosa requires substitution of the offending drug by one containing a steroid, or use of a systemic decongestant. In severe cases, the mucosal swelling becomes irreversible. Such cases require surgical treatment, usually partial turbinate resection (Fig. 2.14).

Allergic and vasomotor rhinitis

The most common perennial allergen is house dust mite.

The most common perennial allergen is house dust mite.

Pollen is the most common seasonal allergen.

Pollen is the most common seasonal allergen.

False-negative results on skin tests are not infrequent.

False-negative results on skin tests are not infrequent.

Sinofacial congestion is common in allergic rhinitis.

Sinofacial congestion is common in allergic rhinitis.

Rhinitis and asthma frequently coexist as part of the same disease process.

Rhinitis and asthma frequently coexist as part of the same disease process.

The mainstay of treatment of allergic and vasomotor rhinitis is medical.

The mainstay of treatment of allergic and vasomotor rhinitis is medical.

Topical nasal steroid preparations are valuable in reducing or abolishing the allergic reactions in many patients and can be prescribed long term.

Topical nasal steroid preparations are valuable in reducing or abolishing the allergic reactions in many patients and can be prescribed long term.

Prolonged application of potent topical vasoconstrictors leads to rhinitis medicamentosa.

Prolonged application of potent topical vasoconstrictors leads to rhinitis medicamentosa.

Nasal polyps and foreign bodies

Nasal polyps

The cause of nasal polyps is not well understood, although they are common in patients with conditions such as asthma and cystic fibrosis (Table 2.3).

| Normal population | 4% |

| Nasal allergy | 1.5% |

| Asthma | 7–15% |

| Aspirin sensitivity | 36–60% |

| Allergic fungal sinusitis | 80% |

| Cystic fibrosis | 27% |

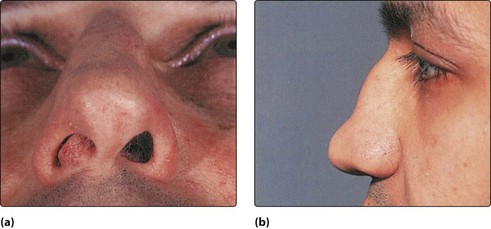

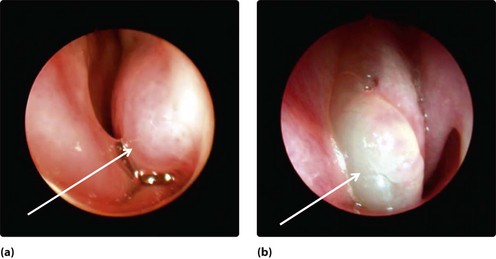

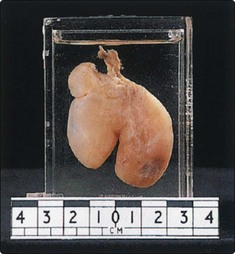

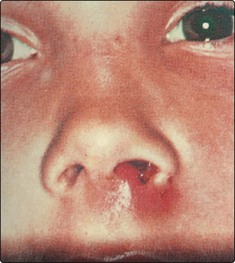

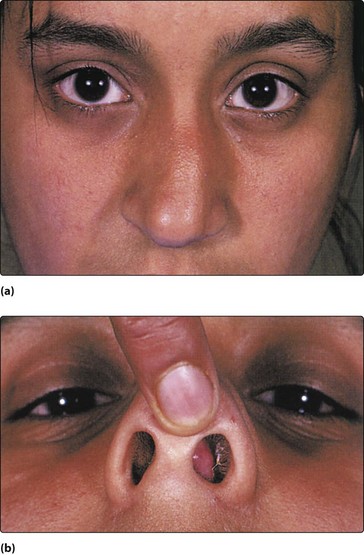

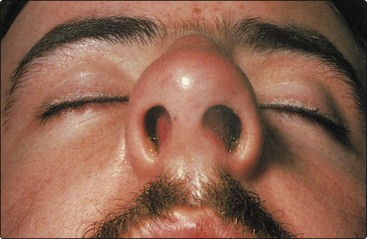

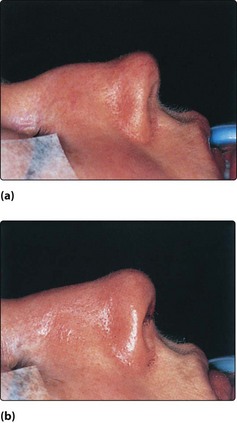

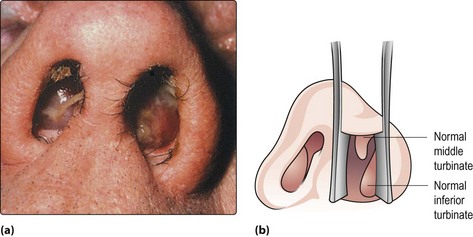

Nasal polyps are ‘bags’ of oedematous mucosa and most frequently arise from the ethmoid cells and prolapse into the nose via the middle meatus. They are nearly always bilateral. If allowed to grow they may present in the nasal vestibule (Fig. 2.15). The cardinal symptom is progressive nasal obstruction. Rhinorrhoea is frequent and occasionally a history of recurrent sinusitis due to ostial blockage is a feature. Hyposmia and anosmia are not uncommon and otological symptoms may occur.

Fig. 2.15 (a) Bilateral nasal polyps presenting in the nasal vestibules. A polyp can easily be confused with a normal inferior turbinate (b), especially if the turbinate is hypertrophic. (See also Fig. 2.8, p. 33.)

Management

Small polyps respond well to topical nasal steroids. Large polyps are treated by a short course of systemic steroids followed by long-term use of topical steroids. Endoscopic ethmoidectomy is indicated for non-responsive and recurrent polyps. Recurrence rates may be reduced by long-term topical steroids, postsurgery. Any chronic sinus infection should be treated in conjunction with nasal polypectomy. Routine management strategies for the associated allergy or asthma should also be instituted (pp. 34–35).

Antrochoanal polyp

The antrochoanal polyp is uncommon. It is usually unilateral and commences as oedematous lining in the maxillary sinus. This prolapses, usually via a posterior accessory ostium, into the nasal cavity and enlarges towards the posterior choana and nasopharynx. The patient, commonly a young adult, complains of unilateral nasal obstruction, which is worse on expiration due to the ball valve effect of the polyp in the posterior choana. If significantly large it may block both choanae and cause otological symptoms due to obstruction of the Eustachian tube (Fig. 2.16). Patients occasionally present so late that the polyp has enlarged behind the soft palate and hangs visibly in the oropharynx.

Neoplastic polyps

Neoplastic polyps (p. 110) are invariably unilateral and cause progressive symptoms: nasal obstruction, epiphora (blocking of the vasolacrimal duct), epistaxis and foul-smelling nasal discharge. They are frequently fleshy in appearance and bleed on palpation. Biopsy is mandatory.

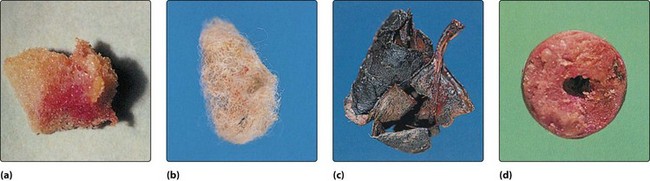

Nasal foreign bodies

Young children (and on occasion, psychiatric cases) are the main patients who insert foreign bodies into the nose. The variety of foreign bodies is protean (Fig. 2.17), but readily available items such as foam rubber, peas and small stones are frequent. Inorganic objects may be in situ for long periods before producing symptoms. However, organic objects, such as paper, wool and vegetable material, produce a brisk mucosal reaction and hence rapid onset of symptoms (Fig. 2.18).

Clinical features

The child is usually calm, although prior clumsy attempts at removal may have caused distress. Usually, the parents provide a sound history which an older child frequently denies. The cardinal sign is a unilateral nasal discharge which is foul smelling if the foreign body has been present for any length of time (Fig. 2.18). Excoriation of the nasal vestibular skin and upper lip may be present. The foreign body frequently impacts in the lower part of the nose and on occasions simply rests in the nasal vestibule. Unless there is a marked infection, visualization is usually possible in good light by elevating the nasal tip gently with the thumb.

Management

In a cooperative child, the foreign body may be either grasped by cupped forceps or flicked out with a blunt hooked probe. An adult may need to restrain a young child. The limbs are usually wrapped in a blanket and the head is held steady (Fig. 2.19). A general anaesthetic will be required in all other instances, as inept attempts could push the object further back with the subsequent risk of inhalation or traumatic haemorrhage. In some instances it is safer to deliver the object via the nasopharynx. The other nostril must be examined to exclude a second foreign body.

Rhinolith

Rhinolith is the term applied to a large foreign body found in the nose of some adults. It is composed of deposits of calcium and magnesium on a nidus such as a piece of gauze or clotted blood. There is frequently a history of nasal packing for epistaxis many years previous (Fig. 2.20).

Clinical features and management

Nasal polyps and foreign bodies

The majority of nasal polyps are bilateral and painless.

The majority of nasal polyps are bilateral and painless.

The prevalence of polyps increases with age.

The prevalence of polyps increases with age.

Beware of unilateral bleeding polyps. They may be neoplastic and should be biopsied.

Beware of unilateral bleeding polyps. They may be neoplastic and should be biopsied.

Nasal polyps are extremely rare in children.

Nasal polyps are extremely rare in children.

A foul-smelling unilateral nasal discharge in a child requires exclusion of a nasal foreign body.

A foul-smelling unilateral nasal discharge in a child requires exclusion of a nasal foreign body.

Beware: foreign bodies can be inhaled.

Beware: foreign bodies can be inhaled.

Resort to removal under general anaesthesia if the patient is uncooperative, or removal is difficult. The patient will thank you.

Resort to removal under general anaesthesia if the patient is uncooperative, or removal is difficult. The patient will thank you.

Nasal infections

Common cold

Management

The patient should preferably be isolated, as the infection is highly contagious. Treatment is symptomatic as the disease is self-limiting. Steam inhalations and topical nasal decongestants may provide some relief from nasal obstruction. The constitutional symptoms of pyrexia and muscular pains are best controlled by an antipyretic such as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or paracetamol. Antibiotics may be required if bacterial complications ensue (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4 Complications of acute coryza

Nasal vestibulitis

Excoriation of the skin of the nasal vestibule may be due to a vast array of local and general conditions. In the former category, nose picking, a dislocated columella and rhinorrhoea from nasal allergy are common (Fig. 2.21). Herpes simplex and zoster vesicles may occur in the anterior nares (Fig. 2.22). In children, the purulent nasal discharge from a foreign body frequently causes a vestibulitis (see Fig. 2.18, p. 37). Generalized eczema can also affect the nasal vestibule. The most common bacteria causing vestibulitis are the staphylococci, a commensal in the anterior nares of some individuals (p. 39).

Nasal furunculosis

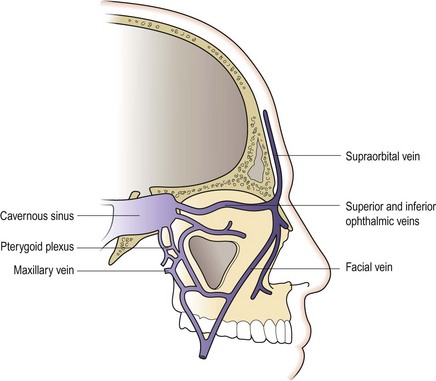

The nose is tender to touch and red (Fig. 2.23). A swab should be taken and the patient commenced on systemic and topical antibiotics. Patients should be advised not to squeeze out pus as there is a potential risk of spreading infection to the cavernous sinus via the facial veins.

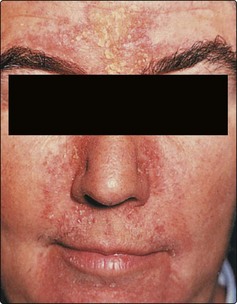

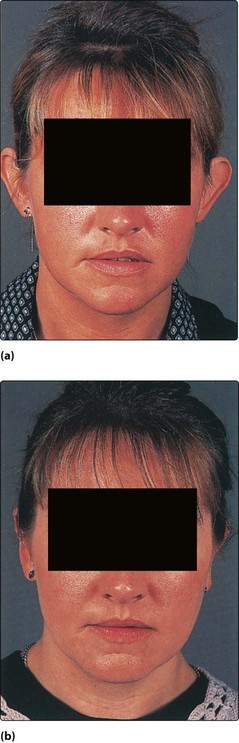

Specific nasal dermatitides

Specific dermatitides are rare in the nasal vestibule. Occasionally the condition may be part and parcel of a generalized skin condition, such as psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis and rosacea (Figs 2.24 and 2.25). These conditions usually resolve by ensuring that the area is kept clean and covered with a steroid antibiotic ointment or barrier cream.

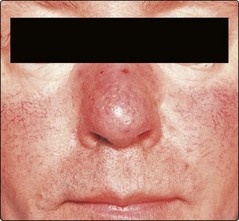

Lupus pernio

The skin may be involved in sarcoidosis (Boeck’s disease), which is a granulomatous disease of unknown cause. This may manifest as erythema nodosum, which can be associated with disease of the nasal skin (lupus pernio). In the nose these present as bluish-red nodules (Fig. 2.26).

Nasal septal pathologies and choanal atresia

Septal deflection

Clinical features

Unilateral nasal obstruction is the main complaint, although an S-shaped deflection can cause bilateral symptoms. A variety of other features such as crusting, facial pain, nasal discharge and epistaxis may be attributed to deflection of the septum. Examination reveals the deflection and, frequently, an associated compensatory hypertrophy of the inferior turbinate on the opposite side (Fig. 2.27). Sometimes an external deformity of the nasal bridge is caused by a deviated septum (Fig. 2.28).

Septal haematoma

Septal haematoma is caused by nasal trauma, which can frequently be quite mild (p. 43). It is most common in children, as the mucoperichondrium is only loosely adherent to the underlying cartilage.

Clinical presentation

Severe nasal obstruction is caused by haemorrhage into the subperichondrial space (Fig. 2.30). Marked tenderness is not a feature unless the haematoma subsequently becomes infected. If an abscess supervenes, cartilage necrosis is inevitable and results ultimately in collapse of the nose and an ugly external deformity (saddle nose).

Septal perforation

There are many causes of a septal perforation, with previous septal surgery on the list (Table 2.5). In many cases it is not possible to implicate any specific aetiology. The majority of perforations are located in the anterior cartilaginous portion of the septum. Classically, syphilitic infection involves the more posterior bony septum.

| Trauma | Neoplasia |

|---|---|

| Nasal surgery | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Physical (repeated cauterization) | Malignant granuloma |

| Digital | Basal cell carcinoma |

| Infection | Miscellaneous |

| Syphilis | Chrome gases |

| Tuberculosis | Cocaine sniffing |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | |

| Idiopathic |

Choanal atresia

Clinical features

Bilateral cases present at birth with severe respiratory difficulties as neonates are obligate nasal breathers and have not acquired the adult habit of mouth breathing. Unilateral choanal atresia usually presents later in life with symptoms of complete unilateral nasal blockage and mucoid discharge. At birth, the diagnosis is made by the inability to pass a soft catheter pernasally, and confirmed by the demonstration of the atretic plate with CT scanning (Fig. 2.31). In adults, nasal endoscopy may reveal the blocked posterior choana.

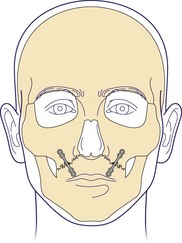

Management

Bilateral atresia is a neonatal emergency; an oral airway is inserted and fixed in position. Pernasal or transpalatal surgical approaches can be employed, depending on the precise nature of the atresia. Indwelling tubes are inserted (Fig. 2.32) to prevent reclosure. Regular bougienage may be necessary for many months after surgery. In unilateral cases, surgery can be delayed.

Facial trauma

Bony trauma

In general, only displaced fractures will require surgical correction.

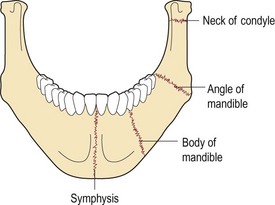

Mandibular fractures

The common sites of mandibular fractures are shown in Figure 2.33. The weakest part of the mandible is the condylar neck; even indirect trauma may cause fractures at this site.

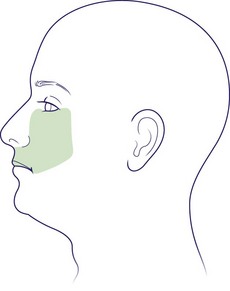

Malar fractures

Malar fractures are common and usually follow a direct blow to the cheek bone or zygoma (Fig. 2.34).

Maxillary fractures

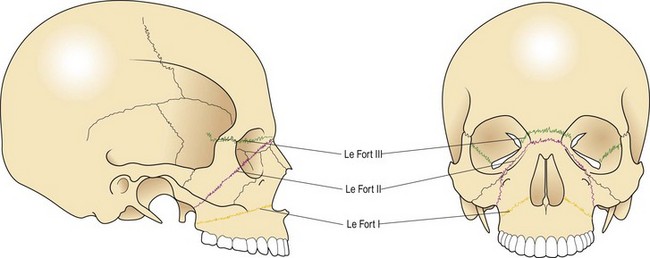

A French doctor by the name of Le Fort described the three most common fractures of the maxillary facial bone. These have been named Le Fort I, II and III fractures (Fig. 2.35). The maxilla provides a shock-absorbing function to prevent severe damage to the skull and intracranial contents. A Le Fort I fracture line passes through the inferior wall of the antrum and allows the tooth-bearing segments of the upper jaw to move in relation to the nose. A Le Fort II allows the maxilla and the nose, as a block, to move in relation to the frontal bone and zygoma. The most severe trauma produces a Le Fort III, which separates the facial bones from the skull base.

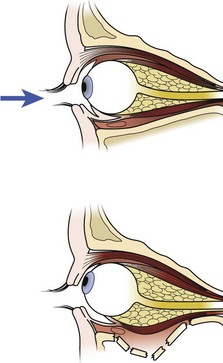

Orbital blow-out fracture

Orbital blow-out fracture is usually caused by direct trauma which pushes the eye into the orbit, thus increasing the pressure in a relatively closed cavity. The weakest part of the cavity, the orbital floor, is fractured with extrusion of orbital contents into the maxillary antrum (Figs 2.37 and 2.38).

Nasal fractures

Facial trauma

Facial trauma can result in life-threatening haemorrhage, respiratory obstruction and inhalation injury.

Facial trauma can result in life-threatening haemorrhage, respiratory obstruction and inhalation injury.

Most facial fractures can be diagnosed on clinical examination.

Most facial fractures can be diagnosed on clinical examination.

Always examine for ocular involvement.

Always examine for ocular involvement.

Intraoral examination is mandatory.

Intraoral examination is mandatory.

The infraorbital and inferior dental nerves are very commonly injured.

The infraorbital and inferior dental nerves are very commonly injured.

Unstable fractures will require appropriate forms of splinting.

Unstable fractures will require appropriate forms of splinting.

Most nasal fractures are produced by lateral traumatic forces.

Most nasal fractures are produced by lateral traumatic forces.

Correction of nasal fractures should be either immediate or after the swelling has resolved at about 7–10 days.

Correction of nasal fractures should be either immediate or after the swelling has resolved at about 7–10 days.

Complications of facial trauma

Emergency treatment will be required for:

Respiratory obstruction

Management

It is important to restore the airway immediately. This may be simply achieved by removing any obstructing object from the mouth or pulling the jaw forward to overcome the posterior displacement of the tongue (Fig. 2.39). Intubation or tracheostomy should be performed if a secure airway is not rapidly obtained.

Haemorrhage

Some degree of haemorrhage is the rule in facial trauma. Usually this settles spontaneously or can be easily controlled by direct pressure. Torrential haemorrhage may occur and is invariably due to major blood vessel damage caused by a bony fracture or sharp object. In the nose, a fracture of the lamina papyracea can tear the anterior ethmoidal artery (Fig. 2.40) to give brisk epistaxis (p. 48). Division of major arteries in the neck results in severe haemorrhage. Associated neck trauma can lead to bleeding from the carotid tree.

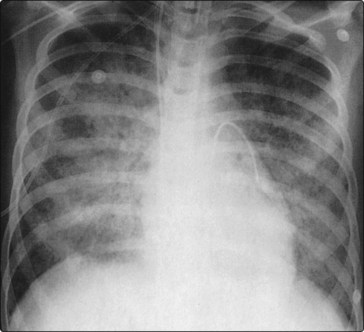

Inhalational injuries

Inhalational injuries are a potentially fatal complication, especially in severe trauma with loss of consciousness. In a comatose patient, blood and gastric contents may be inhaled. If a shock lung syndrome or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) develops, the morbidity and mortality are very high (Fig. 2.41).

Other complications

Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea

The diagnosis may be confirmed by the detection of fluorescein in the nose after injection via a lumbar puncture (Fig. 2.42). More recently, high-resolution CT scanning has provided a very effective way of localizing fractures (Fig. 2.43).

Cavernous sinus thrombosis

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a potentially fatal complication of infected facial wounds. It is a retrograde infection, via the facial veins, resulting in an intracranial thrombosis (Fig. 2.44).

Septal haematoma

Septal haematoma can occur as a complication of facial trauma. This condition is discussed fully on page 40.

Sensory loss

Sensory loss, producing an area of anaesthesia, is a common accompaniment of fractures of the infraorbital region with damage to the infraorbital nerve (Fig. 2.45). Post-traumatic anosmia is not an infrequent occurrence. Even relatively minor trauma may damage the delicate olfactory nerve filaments. Anosmia is invariable if the cribriform plate has been fractured. Unfortunately, there is no prospect of recovery.

Facial plastic surgery

Excision of facial lesions

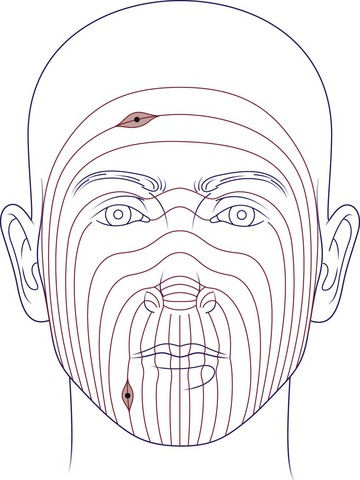

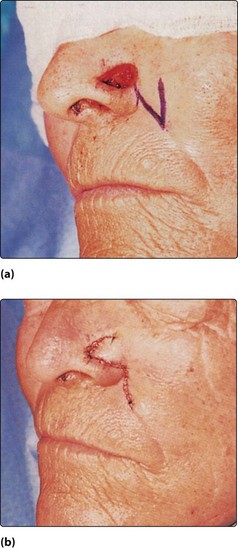

Excision of lesions should be performed with the incisions placed in the relaxed skin tension lines of the face (Fig. 2.46). This produces the least tension on the repair and the best cosmetic scar. Larger defects which cannot be closed by simple undermining and advancement of the edges require a flap or free skin graft (Fig. 2.47).

Laser surgery has gained popularity recently for facial lesions and for resurfacing areas of the face. The different types of laser (wavelength) have separate applications. carbon dioxide lasers vaporize skin and, when combined with an oscillating beam, can precisely remove tissue to a calculated depth, allowing regeneration from the adnexae (Fig. 2.48). Pigmented lesions, e.g. telangiectasia, will absorb the green light of an argon, potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) or pulsed diode laser, producing selective thrombosis in vessels.

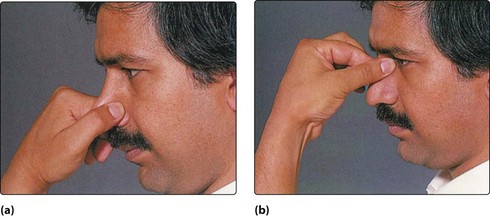

Rhinoplasty

There are many variations in nasal form which can be altered by trauma or disease. Patients request rhinoplasty for a variety of reasons: females often because the nose is too large, usually with a dorsal hump (Fig. 2.49); males frequently because of a combination of functional and cosmetic problems, often trauma related. Deviated noses invariably have an associated septal deformity which it is essential to identify and correct at the same time as the rhinoplasty.

Most reduction rhinoplasties are performed as closed procedures, i.e. the incisions are entirely within the nasal fossa. Selected post-trauma cases and revisions may be approached by an external incision across the columella, allowing an extended range of surgical options (Figs 2.50 and 2.51).

Otoplasty

Prominent ears are a source of ridicule for many children, and patients often feel self-conscious in adult life. The deformity is usually a combination of a deep conchal bowl and failure of the antehelix to develop. The latter, if recognized at birth, can be treated with taping over a splint within the first 5 days. Otherwise, correction is best left until just before school entry, but can be considered at any age after about 3.5 years. Various techniques using cartilage scoring and sutures are employed, usually under general anaesthesia for children, and the bandages are removed at about 10 days. A sweatband is worn at night for a further 2–3 weeks. Otoplasty in an adult, particularly if it is unilateral, can be performed under local anaesthetic (Fig. 2.52).

Epistaxis

Aetiology

It is useful to divide the causes of epistaxis into local and general (Table 2.6). Approximately 90% of epistaxis occurs in Kiesselbach’s plexus, localized at the anterior portion of the septum (Little’s area; p. 30). Here, a rich vascular anastomotic supply is formed by end arteries.

| Type | Causes |

|---|---|

| Local | Idiopathic* |

| Infection | |

| Trauma* | |

| Neoplasia | |

| Foreign body | |

| General | Hypertension |

| Drugs (anticoagulants) | |

| Blood diseases (leukaemia) | |

| Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia |

*Most common causes of epistaxis.

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler–Weber–Rendu disease), which is characterized by abnormal capillaries, is a potent cause of recurrent epistaxis (Fig. 2.53). The condition can also cause haematuria, melaena and subarachnoid or cerebral haemorrhage. All types of nasal and paranasal neoplasia may produce nasal haemorrhage, but particularly a benign vascular tumour called a juvenile angiofibroma (p. 109).

Management

Management of epistaxis involves four steps:

First-aid measures

The nostrils should be pinched together tightly and respiration continued through the mouth. A suitable container placed under the chin will catch any blood. The subject should sit upright to lower the blood pressure and lean forward so as not to swallow blood. These manoeuvres comprise ‘Trotter’s method’ for the control of epistaxis. It is useless to compress the bony root of the nose (Fig. 2.54).

Controlling the bleeding

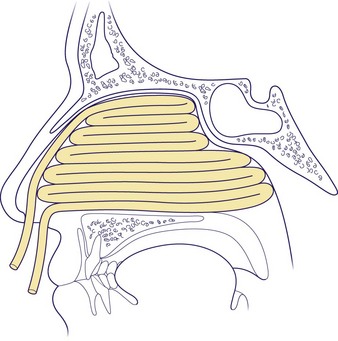

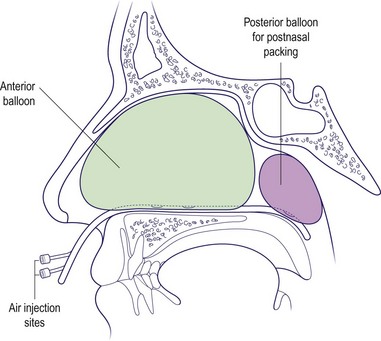

A nasal pack will be required if no clear bleeding point is discernible. Traditionally, the pack consists of ribbon gauze impregnated with bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP). The nose must be cleared of clots before insertion and the pack built up in layers starting in the floor (Fig. 2.55). It is important to appreciate that, in an adult, the distance between the anterior nares and posterior choanae is upwards of 6 cm. An inflatable balloon tamponade can be used as an alternative method of packing (Fig. 2.56), or microporous sponges.

Continued haemorrhage despite an anterior pack is probably due to bleeding from the posteriorly placed branches of the sphenopalatine artery and may require insertion of a postnasal pack. Specialized nasal inserts with a double balloon will allow pressure to be exerted in both the postnasal and anterior nasal spaces (Fig. 2.56). A formal gauze postnasal pack usually requires a general anaesthetic for insertion. Its dimensions should be similar to the distal phalanx of the patient’s thumb, as this compares favourably with the size of the postnasal space.

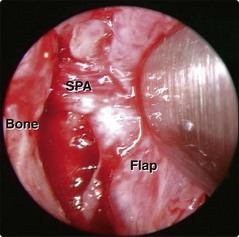

If, despite these measures, epistaxis continues or recurs then a formal examination under anaesthetic will be needed. An obvious bleeding point may be seen endoscopically and controlled by diathermy. If not, arterial ligation of the sphenopalatine artery endoscopically, or ligation of the maxillary artery by an approach via the maxillary antrum, may be necessary (Fig. 2.57). Rarely, the external carotid artery in the neck may be ligated.

General measures

Epistaxis

Most epistaxis is due to bleeding from Little’s area and is easily managed by cauterization under local anaesthesia.

Most epistaxis is due to bleeding from Little’s area and is easily managed by cauterization under local anaesthesia.

Inflatable balloons are more convenient to insert and less traumatic to the nasal mucosa than ribbon gauze packs.

Inflatable balloons are more convenient to insert and less traumatic to the nasal mucosa than ribbon gauze packs.

Always consider both local and general pathologies in the aetiology of epistaxis. Blood loss is often underestimated.

Always consider both local and general pathologies in the aetiology of epistaxis. Blood loss is often underestimated.

Acute and chronic sinusitis

Sinusitis is an inflammatory process involving the lining of the paranasal sinuses.

Acute sinusitis

The diagnosis of sinusitis is not usually difficult (Figs 2.58 and 2.59), and more than one sinus is usually involved. Facial swelling suggests complications of sinusitis, dental disease or uncommonly malignancy and therefore demands further investigation.

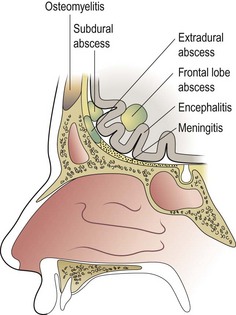

Acute frontal sinusitis

Acute frontal sinusitis is a potentially serious condition because of the risk of intracranial complications, which still have a high morbidity and significant mortality (Fig. 2.61).

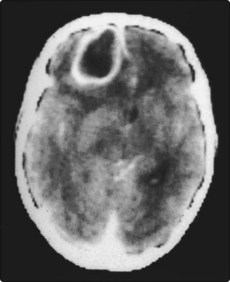

Severe frontal headache and tenderness over the sinus are usually present. CT scanning is indicated if there are suspected complications, such as orbital or intracranial involvement (Figs 2.62 and 2.63).

Treatment

Treatment of acute frontal sinus infection should involve:

high-dose broad-spectrum antibiotics; reviewed after identifying causative organism by culture of pus

high-dose broad-spectrum antibiotics; reviewed after identifying causative organism by culture of pus

topical vasoconstrictor nose drops to decongest the nasal mucosa and encourage normal sinus ventilation

topical vasoconstrictor nose drops to decongest the nasal mucosa and encourage normal sinus ventilation

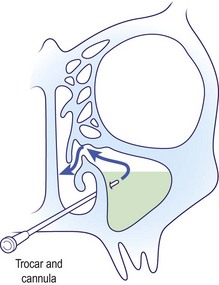

resolution of concomitant maxillary, ethmoidal and sphenoidal sinusitis (pansinusitis) using proof puncture (Fig. 2.60) or endoscopic drainage.

resolution of concomitant maxillary, ethmoidal and sphenoidal sinusitis (pansinusitis) using proof puncture (Fig. 2.60) or endoscopic drainage.

trephination and drainage, if necessary, to release the pus and culture infective material (Fig. 2.64).

trephination and drainage, if necessary, to release the pus and culture infective material (Fig. 2.64).

balloon dilatation or endoscopic drainage, using specially designed equipment.

balloon dilatation or endoscopic drainage, using specially designed equipment.

Chronic sinusitis

Ethmoid sinus

Intranasal ethmoidectomy, often performed using an endoscope, is becoming the preferred surgical option for recurrent acute or chronic sinusitis. Via this route a physiological fenestration can be made into the ethmoid sinus, which in most cases will allow restoration of normal mucociliary clearance.

Intranasal ethmoidectomy, often performed using an endoscope, is becoming the preferred surgical option for recurrent acute or chronic sinusitis. Via this route a physiological fenestration can be made into the ethmoid sinus, which in most cases will allow restoration of normal mucociliary clearance.

External ethmoidectomy involves a facial incision for access. This approach is less common now because of the increased use of endoscopes (Fig. 2.64).

External ethmoidectomy involves a facial incision for access. This approach is less common now because of the increased use of endoscopes (Fig. 2.64).

Maxillary sinus

Antrostomy allows adequate ventilation and drainage. This is now performed via the natural ostium in the ostiomeatal complex (Fig. 2.65).

Antrostomy allows adequate ventilation and drainage. This is now performed via the natural ostium in the ostiomeatal complex (Fig. 2.65).

Caldwell–Luc operation to allow removal of specific chronic infections, e.g. fungus, dentogenic infections, via a sublabial approach to the sinuses. This approach is rarely performed nowadays.

Caldwell–Luc operation to allow removal of specific chronic infections, e.g. fungus, dentogenic infections, via a sublabial approach to the sinuses. This approach is rarely performed nowadays.

Frontal sinus

Frontoethmoidectomy – opening of the frontal sinus and floor in combination with ethmoidectomy to provide drainage into the nose. This is usually performed endoscopically.

Frontoethmoidectomy – opening of the frontal sinus and floor in combination with ethmoidectomy to provide drainage into the nose. This is usually performed endoscopically.

Acute and chronic sinusitis

Many cases of chronic sinusitis are rhinogenic in origin.

Many cases of chronic sinusitis are rhinogenic in origin.

The middle nasal meatus is the region that drains all the major paranasal sinuses, except the sphenoid.

The middle nasal meatus is the region that drains all the major paranasal sinuses, except the sphenoid.

Disease of the middle meatus and ostiomeatal complex results in pathology in the major dependent sinuses.

Disease of the middle meatus and ostiomeatal complex results in pathology in the major dependent sinuses.

An acute ethmoid sinusitis is mainly a disease of children and can rapidly result in complications, e.g. orbital cellulitis.

An acute ethmoid sinusitis is mainly a disease of children and can rapidly result in complications, e.g. orbital cellulitis.

CT scanning is invaluable in assessing the spread of acute sinus infections.

CT scanning is invaluable in assessing the spread of acute sinus infections.

Head and neck pain I

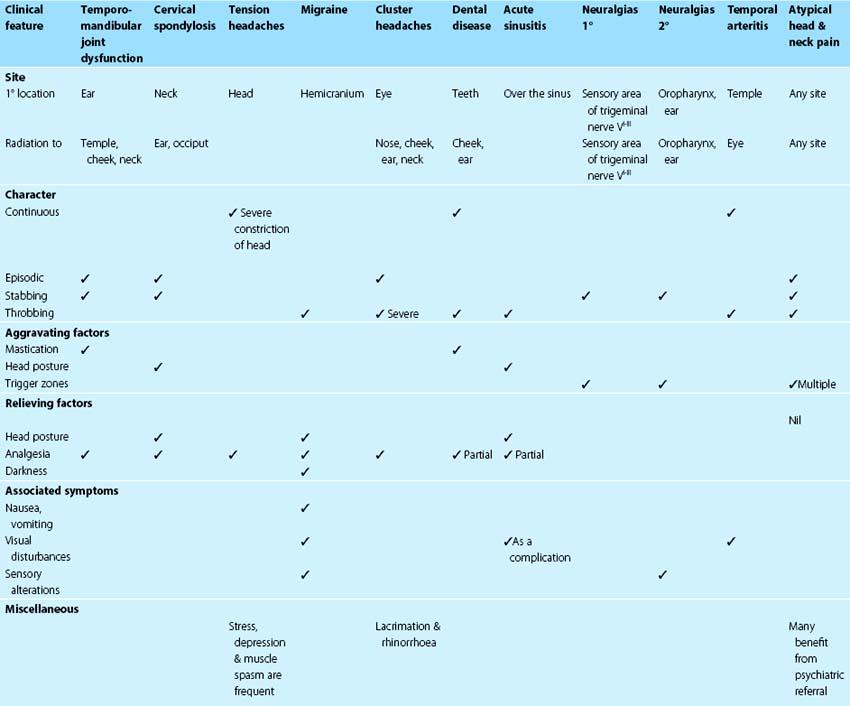

Historically, many clinicians attributed the majority of cases of head and neck pain to sinusitis and other nasal pathologies. However, these symptoms are now known to result from a wide variety of aetiologies. Establishing a precise diagnosis is made difficult by a number of different factors. The sensory innervation of the head and neck is complex, with innumerable pain receptors in a variety of tissues. The face is also a common site for referred pain. The management of head and neck pain demands a detailed history. A series of questions designed to elicit the cardinal clinical features of the head and neck pain will allow certain aetiologies to be unmasked (Table 2.7). The nature of the pain provides vital clues to possible aetiologies. Throbbing pain is usually vascular in origin due either to changes seen in migraine or to the enhanced vascularity in acute sinusitis. Sharp stabbing pains are characteristic of neuralgias, e.g. trigeminal. The position of the head, e.g. as in stooping, tends to aggravate vascular pain due to venous engorgement and is a particular feature of frontal sinusitis. Visual disturbances of a vascular origin are seen commonly in migraine, although they may also be due to optic neuritis. Any specific alteration of sensation such as numbness or hypoaesthesia associated with pain is highly suggestive of neoplastic infiltration of nervous tissue, hence the importance of testing for facial sensation to exclude sensory involvement.

Headaches

Migrainous headaches

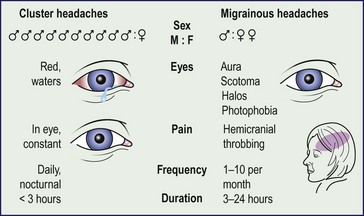

Migraines (Fig. 2.66) occur mainly in women and are hemicranial and paroxysmal. Prodromal eye symptoms such as halos and scotomata are not infrequent. Dilatation of intracranial vessels is the result of the disorder and in many instances can be counteracted with vasoconstrictors such as ergot preparations, beta-blockers or, for acute attacks, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) agonists.

Cluster headaches

Cluster headaches (Fig. 2.66) are synonymous with periodic migrainous and ciliary neuralgia. The symptoms characteristically occur in the early hours, usually in clusters with periods of relief lasting several months. Prophylactic vasoconstrictors and 5-HT agonists, such as those employed for migraine, are very effective.

Neuralgic causes of head and neck pain

Secondary neuralgias

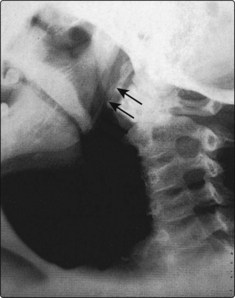

An acoustic neuroma expanding in the cerebellopontine angle can cause pressure on the trigeminal and glossopharyngeal nerves. An elongated styloid process may give rise to symptoms of glossopharyngeal neuralgia by irritating the nerve as it passes the tonsil fossa (Fig. 2.67). Nasopharyngeal tumours can erode the skull base and cause invasion and compression of the trigeminal nerve.

Postherpetic neuralgia is a frequent complication of herpes zoster infection. The ophthalmic division of the trigeminal is commonly affected. Pain may continue for several months after the vesicular rash has subsided (Fig. 2.68).

Head and neck pain I

In the diagnosis of head and neck pain, a clinical history is more useful than investigations.

In the diagnosis of head and neck pain, a clinical history is more useful than investigations.

Tension headaches are the most common cause of head and neck pain. The physical signs elicitable are limited or nil.

Tension headaches are the most common cause of head and neck pain. The physical signs elicitable are limited or nil.

Temporal arteritis may cause blindness. If the diagnosis is suspected, steroid treatment should be commenced on clinical grounds.

Temporal arteritis may cause blindness. If the diagnosis is suspected, steroid treatment should be commenced on clinical grounds.

Primary neuralgias are not accompanied by neurological signs.

Primary neuralgias are not accompanied by neurological signs.

Secondary neuralgias may show evidence of nerve deficits, and require imaging – usually MRI or CT.

Secondary neuralgias may show evidence of nerve deficits, and require imaging – usually MRI or CT.

Head and neck pain II

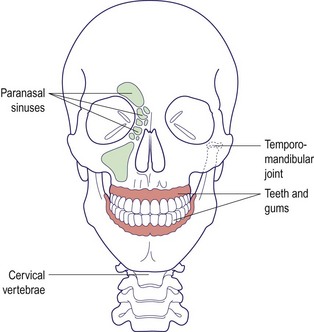

Miscellaneous causes of head and neck pain

A variety of conditions can result in referred head and neck pain (Fig. 2.69). Dental pathology, such as carious teeth and unerupted third molars, are common causes. Abnormalities of the cervical spine and spasm of the cervical muscles may also produce pain in the neck radiating to the ear and occiput.

Abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint

Temporomandibular joint abnormalities are a prevalent cause of facial pain. Referred otalgia is a very common symptom in this condition (p. 13), but pain may be felt in the temple and cheek. The nerve endings in the joint are stimulated by stress due to malocclusion stretching the joint capsule. The discomfort may be noted with jaw movements, e.g. chewing. Edentulous patients are frequent sufferers. Palpation may elicit pain over the joint and crepitus may be felt and heard. Treatment consists of procedures to correct the bite and muscle relaxants to relieve associated muscular spasm.

Paranasal sinus disease

Acute sinus infection produces pain localized over the involved sinus(es) and is easily diagnosed owing to constitutional upset and the invariable presence of nasal symptoms. However, some cases of facial pain may be due to anatomical narrowing and localized disease in the middle meatus producing secondary sinus pathology in the maxillary, ethmoid and frontal sinuses (Fig. 2.70). Endoscopic surgical correction of the narrowed ostiomeatal complex will result in abolition of symptoms and restoration of normal mucosa (p. 51).

Atypical head and neck pain

Head and neck pain II

Acute and chronic sinusitis can result in head and neck pain.

Acute and chronic sinusitis can result in head and neck pain.

Many causes of head and neck pain are idiopathic.

Many causes of head and neck pain are idiopathic.

Referred causes of head and neck pain are very common.

Referred causes of head and neck pain are very common.

Abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint and arthritis of the cervical spine are extremely common causes of head and neck pain.

Abnormalities of the temporomandibular joint and arthritis of the cervical spine are extremely common causes of head and neck pain.

Dental disease is a common aetiology of head and neck pain.

Dental disease is a common aetiology of head and neck pain.