Normal pregnancy and antenatal care

Aims and patterns of routine antenatal care

The basic aims of antenatal care are:

• To ensure optimal health of the mother throughout pregnancy and in the puerperium.

• To detect and treat disorders arising during pregnancy that relate to the welfare of both the mother and the fetus and to ensure that the pregnancy results in a healthy mother and a healthy infant.

The ways by which these objectives are achieved will vary according to the initial health and history of the mother and are a combination of screening tests, educational and emotional support and monitoring of fetal growth and maternal health throughout the pregnancy.

The risk of substance abuse in pregnancy

Smoking

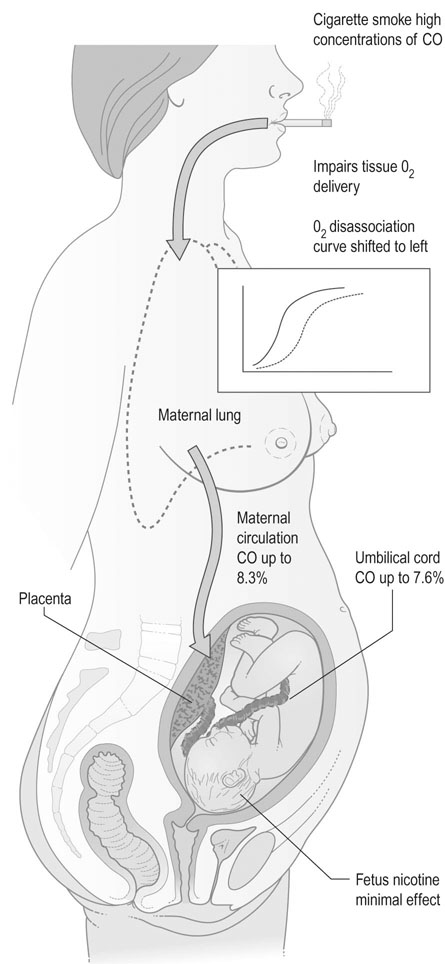

Smoking has an adverse effect on fetal growth and development and is therefore contraindicated in pregnancy. The mechanisms for these effects are as follows (Fig. 7.1):

• The effect of carbon monoxide on the fetus. Carbon monoxide has an affinity for haemoglobin 200 times greater than oxygen. Fresh air contains up to 0.5 ppm of carbon monoxide, but in cigarette smoke values as high as 60 000 ppm may be detected. Carbon monoxide shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the left in both fetal and maternal haemoglobin. Maternal carbon monoxide saturation may rise to 8% in the mother and 7% in the fetus, so that there is specific interference with oxygen transfer.

• The effect of nicotine on the uteroplacental vasculature as a vasoconstrictor. Animal studies on the effect of infusions of nicotine on cardiac output have shown that high-dose infusions produce a fall in cardiac output and uteroplacental blood flow. However, at levels up to five times greater than those seen in smokers there are no measurable effects and it is therefore unlikely that nicotine exerts any adverse effects by reducing uteroplacental blood flow.

• The effect of smoking on placental structure. Some changes are seen in the placental morphology. The trophoblastic basement membrane shows irregular thickening and some of the fetal capillaries show reduced calibre. These changes are not consistent or gross and are not associated with any gross reduction in placental size. The morphological changes have not been demonstrated in those women subjected to passive smoking.

• The effect on perinatal mortality. Smoking during pregnancy reduces the birth weight of the infant and also reduces the crown–heel length. Perinatal mortality is increased as a direct effect of smoking and this risk has been quantified at 20% for those women who smoke up to 20 cigarettes per day and 35% in excess of one packet per day. Mothers should be advised to stop smoking during pregnancy.

The booking visit

The details of antenatal history and routine clinical examinations are discussed in Chapter 6. However, certain observations should be stressed at the first visit and it is preferable that these observations should be made within the first 10 weeks of pregnancy. The measurement of maternal height and weight is important and has value in prediction of pregnancy outcomes. Women with a low body mass index (BMI; less than 20, where BMI is estimated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2)) are at increased risk of fetal growth restriction and perinatal mortality. Women with a high BMI are increasingly recognized as being at increased antenatal and intrapartum risk, with the risks beginning to rise from a BMI of 30.

Recommended routine screening tests

Blood group and antibodies

The use of anti-D immunoglobulin

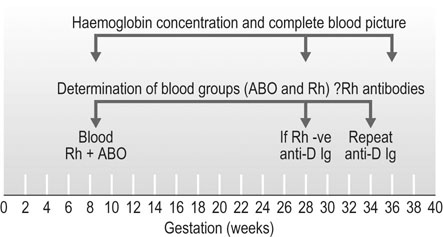

Now that anti-D Ig is readily available, it has become standard practice to give anti-D Ig prophylaxis at 28 and 34 weeks gestation (Fig. 7.2). This will prevent maternal immunization by a Rh-positive fetus in all but 0.2% Rh-negative women, in whom the infusion of cells from the fetus overwhelms the dose of antibody administered. This is in addition to the above indications.

Infection screening

Rubella

Human immunodeficiency virus

Seropositive mothers always have seropositive babies due to transplacental transmission of antibodies, but this may not indicate active infection in the baby. However, up to 45% of babies will have contracted HIV if active management programmes are not used. As treatment is highly effective in reducing transmission rates to less than 2% there is a strong case for routine screening of all women. These strategies include caesarean section, avoidance of breastfeeding and antiretroviral therapy in both the antenatal and intrapartum period as well as for the newborn (see Chapter 9).

Gestational diabetes

History of a previous pregnancy complicated by gestational diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance

History of a previous pregnancy complicated by gestational diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance

First-degree relative with diabetes

First-degree relative with diabetes

Previous unexplained stillbirth

Previous unexplained stillbirth

Previous macrosomic infant with a birth weight in excess of 4 kg

Previous macrosomic infant with a birth weight in excess of 4 kg

Maternal weight > 100 kg or BMI > 35

Maternal weight > 100 kg or BMI > 35

• Universal screening: The screening of all women at 26–28 weeks gestation will identify more women with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes than those screened by risk factors alone. A modified GTT involving a loading dose of 50 g and 1 hour blood glucose (glucose challenge test, GCT) is considered positive if the blood glucose exceeds 7.7 mmol/L. This is then followed by a formal GTT.

Most units prefer to screen at-risk populations because of the practical difficulties and costs of screening the whole population, particularly in large maternity hospitals.

Screening for fetal anomaly

Structural fetal anomalies account for some 20–25% of all perinatal deaths and for about 15% of all deaths in the first year of life. There is therefore a strong case to be made for early detection and termination of pregnancy offered where this is appropriate. The frequency of the major structural anomalies is shown in Table 7.1. Congenital anomalies are one of the markers of socioeconomic deprivation.

Table 7.1

| Type of anomaly | Frequency (per 1000) |

| Cardiovascular | 6 |

| Craniospinal | 3–7 |

| Renal tract | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1 |

These anomalies are generally detectable by ultrasound scanning and this will be discussed in Chapter 10.

Nuchal translucency and biochemical screening

Screening for trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome) has become routine in most antenatal services, but not in all countries. The logical consequence of such a programme is to offer invasive testing then termination of pregnancy where there is evidence of aneuploidy. Although the value of the test is reduced if termination is not an option, a positive result can help parents prepare for the birth of an affected infant. Screening is by the use of biochemical and ultrasound tests. It is important that women understand that these are screening tests and therefore have their limitations. They will not detect every case and high-risk results do not necessarily mean that the baby is affected. Despite the increased incidence of Down’s syndrome in mothers over 35 years, screening on the basis of age alone will not detect most affected fetuses and it is recommended to offer screening to all women. The major modality for screening for Down’s syndrome is the use of ultrasound measurement of nuchal translucency, a measurement of fluid behind the fetal neck (see Chapter 10, Fig. 10.6). This is combined with maternal age and the results of biochemical tests to provide a risk for this fetus of trisomy 21, 13 and 18 (see Chapter 10).

Schedules of routine antenatal care

Subsequent visits

Although the pattern of antenatal care will vary with circumstances and with the normality or otherwise of the pregnancy, a general pattern of visits will partly revolve around the demands of the screening procedures and the obstetric and medical history of the mother. The measurement of blood pressure is performed at all visits and the measurement of symphysis/fundal height should be recorded, even accepting that this observation has a limited capacity to detect fetal growth restriction. Serial ultrasound measurements would have a greater detection rate if performed at every visit, but this is not practicable or necessary for women who are not considered to be at high risk. A suggested regime for antenatal visits is listed in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2

| 8–12 weeks | Initial visit, confirmation of pregnancy, search for risk factors in maternal history. Cervical smear where indicated, advice on general health, smoking and diet. Discuss and organize screening procedures. Check maternal weight and give advice on recommended folic acid and iodine supplements. Dating scan and scan for multiple pregnancies |

| 11–14 weeks | Screening for trisomies with ± nuchal translucency scan and blood tests if requested. Confirm booking arrangements. Offer dietary supplements of iron if any evidence of anaemia |

| 16 weeks | Check all blood results. Offer routine ultrasound anomaly scan |

| 20 weeks | Check ultrasound result. BP. Fundal height. |

| 24 weeks | BP, fundal height, fetal activity. |

| 28 weeks | BP, fundal height, fetal activity, full blood count and antibody screen. Administer anti-D if Rh-negative. Glucose tolerance test. |

| 32 weeks | BP, fundal height, fetal activity and fetal growth scan where pattern of fetal growth is in doubt or low lying placenta on anomaly scan |

| 34 weeks | Routine checks, also second dose of anti-D for Rh-negative women, Group B Streptococcus vaginal and rectal swab, full blood count |

| 36 weeks | BP, fundal height, fetal activity, determine presentation |

| 38 weeks | Routine checks, fetal activity, maternal wellbeing |

| 40 weeks | Routine checks, fetal activity, maternal wellbeing |

| 41 weeks | Routine checks, assessment by pelvic examination as to cervical favourability, cardiotocograph, amniotic fluid index. Individualize care with regards to induction of labour and ongoing assessment. |

(Adapted from Kean L (2001) Routine antenatal management. Curr Obstet Gynaecol 11:63–69.)

Antenatal education

Dietary advice

Minerals and vitamins

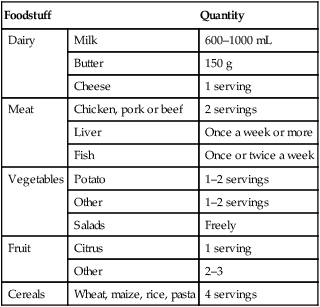

A general protocol for diet in pregnancy is given in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3

General advice on foodstuffs recommended in pregnancy (quantity per day unless otherwise stated)

| Foodstuff | Quantity | |

| Dairy | Milk | 600–1000 mL |

| Butter | 150 g | |

| Cheese | 1 serving | |

| Meat | Chicken, pork or beef | 2 servings |

| Liver | Once a week or more | |

| Fish | Once or twice a week | |

| Vegetables | Potato | 1–2 servings |

| Other | 1–2 servings | |

| Salads | Freely | |

| Fruit | Citrus | 1 serving |

| Other | 2–3 | |

| Cereals | Wheat, maize, rice, pasta | 4 servings |

1 serving = half a cup.

Safe prescribing in pregnancy

The use of prescription and over the counter medications, as well as complementary and alternative medications, is common. Some women will require ongoing treatment of pre-existing medical conditions, e.g. epilepsy or asthma. Some conditions may develop de-novo in pregnancies that require therapy, e.g. gestational diabetes, thromboembolism. Simple analgesics, antipyretics, antihistamines and anti-emetics are all commonly consumed. A discussion of the risks and benefits of individual medications is beyond the scope of this text. Extensive information is available in most drug formularies about the safety of categories of drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Reputable online resources such as www.motherisk.org are available around the clock and often helpful. The safest course before prescribing in pregnancy is to always check. Many medications have been shown to have no adverse outcomes when used in pregnancy or lactation.