Chapter 8 Normal Labor, Delivery, and Postpartum Care

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS, OBSTETRIC ANALGESIA AND ANESTHESIA, AND RESUSCITATION OF THE NEWBORN

Anatomic Characteristics of the Fetal Head and Maternal Pelvis

Anatomic Characteristics of the Fetal Head and Maternal Pelvis

Vaginal delivery necessitates the accommodation of the fetal head to the bony pelvis.

FETAL HEAD

Sutures

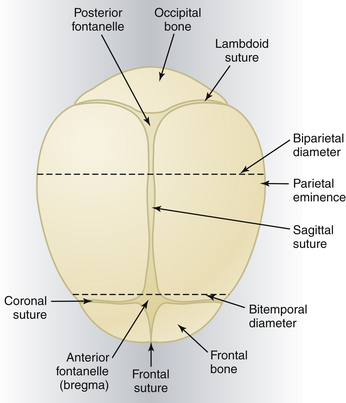

The membrane-occupied spaces between the cranial bones are known as sutures. The sagittal suture lies between the parietal bones and extends in an anteroposterior direction between the fontanelles, dividing the head into right and left sides (Figure 8-1). The lambdoid suture extends from the posterior fontanelle laterally and serves to separate the occipital from the parietal bones. The coronal suture extends from the anterior fontanelle laterally and serves to separate the parietal and frontal bones. The frontal suture lies between the frontal bones and extends from the anterior fontanelle to the glabella (the prominence between the eyebrows).

Landmarks

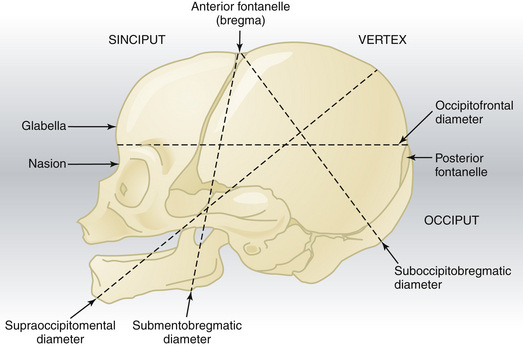

The fetal skull is characterized by a number of landmarks. Moving from front to back, they include the following (Figure 8-2):

Diameters

Several diameters of the fetal skull are important (see Figures 8-1 and 8-2). The anteroposterior diameter presenting to the maternal pelvis depends on the degree of flexion or extension of the head and is important because the various diameters differ in length. The following measurements are considered average for a term fetus:

The transverse diameters of the fetal skull are as follows:

The average circumference of the term fetal head, measured in the occipitofrontal plane, is 34.5 cm.

PELVIC ANATOMY

Pelvic Diameters

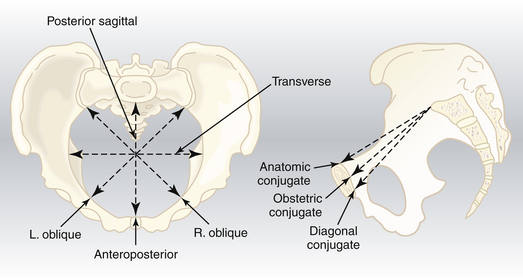

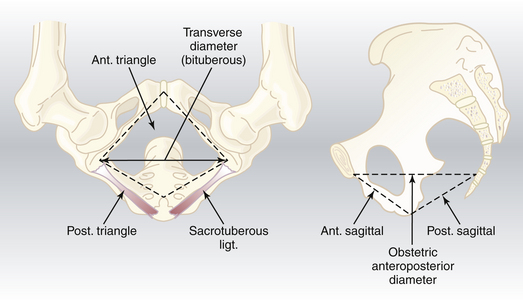

The average lengths of the diameters of each pelvic plane are listed in Table 8-1.

| Pelvic Plane | Diameter | Average Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Inlet | True (anatomic) conjugate | 11.5 |

| Obstetric conjugate | 11 | |

| Transverse | 13.5 | |

| Oblique | 12.5 | |

| Posterior sagittal | 4.5 | |

| Greatest diameter | Diagonal conjugate | 12.75 |

| Transverse | 12.5 | |

| Midplane | Anteroposterior | 12 |

| Bispinous | 10.5 | |

| Posterior sagittal | 4.5-5 | |

| Outlet | Anatomic anteroposterior | 9.5 |

| Obstetric anteroposterior | 11.5 | |

| Bituberous | 11 | |

| Posterior sagittal | 7.5 |

Pelvic Inlet

The pelvic inlet has five important diameters (Figure 8-3). The anteroposterior diameter is described by one of two measurements. The true conjugate (anatomic conjugate) is the anatomic diameter and extends from the middle of the sacral promontory to the superior surface of the pubic symphysis. The obstetric conjugate represents the actual space available to the fetus and extends from the middle of the sacral promontory to the closest point on the convex posterior surface of the symphysis pubis.

Pelvic Outlet

The pelvic outlet has four important diameters (Figure 8-4). The anatomic anteroposterior diameter extends from the inferior margin of the pubis to the tip of the coccyx, whereas the obstetric anteroposterior diameter extends from the inferior margin of the pubis to the sacrococcygeal joint. The transverse (bituberous) diameter extends between the inner surfaces of the ischial tuberosities, and the posterior sagittal diameter extends from the middle of the transverse diameter to the sacrococcygeal joint.

PELVIC SHAPES

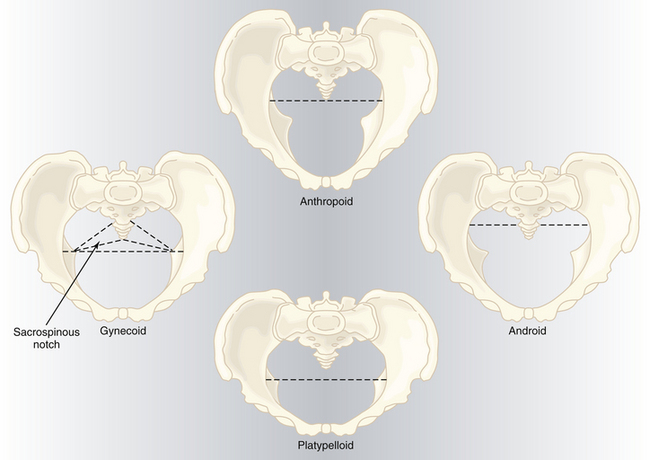

Based on the general bony architecture, the pelvis may be classified into four basic types (Figure 8-5).

Gynecoid

Android

ENGAGEMENT

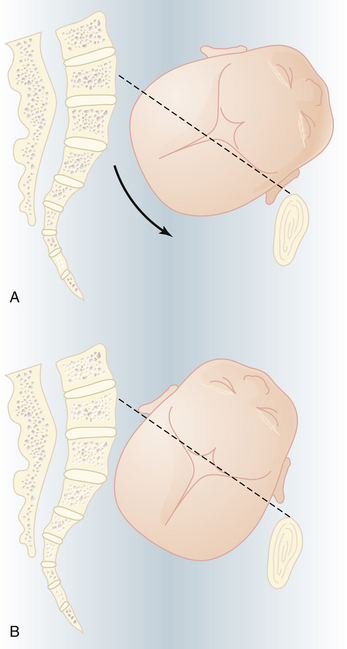

In most women, the bony presenting part is at the level of the ischial spines when the head has become engaged. The fetal head usually engages with its sagittal suture in the transverse diameter of the pelvis. The head position is considered to be synclitic when the biparietal diameter is parallel to the pelvic plane and the sagittal suture is midway between the anterior and posterior planes of the pelvis. When this relationship is not present, the head is considered to be asynclitic (Figure 8-6).

CLINICAL PELVIMETRY

The clinical evaluation is started by assessing the pelvic inlet. The pelvic inlet can be evaluated clinically for its anteroposterior diameter. The obstetric conjugate can be estimated from the diagonal conjugate, which is obtained on clinical examination (see Figure 8-3).

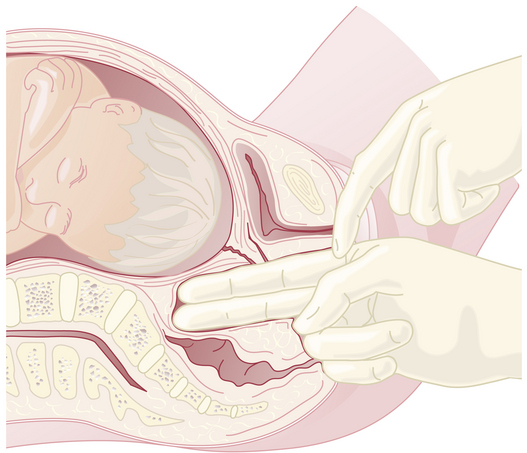

The diagonal conjugate is approximated by measuring from the lower border of the pubis to the sacral promontory using the tip of the second finger and the point where the base of the index finger meets the pubis (Figure 8-7). The obstetric conjugate is then estimated by subtracting 1.5 to 2 cm, depending on the height and inclination of the pubis. Often the middle finger of the examining hand cannot reach the sacral promontory; thus, the obstetric conjugate is considered adequate. If the diagonal conjugate is greater than or equal to 11.5 cm, the anteroposterior diameter of the inlet is considered to be adequate.

PREPARATION FOR LABOR

Before actual labor begins, a number of physiologic preparatory events usually occur.

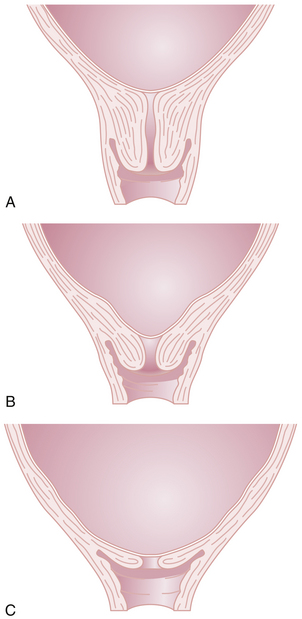

Cervical Effacement

Before the onset of parturition, the cervix is frequently noted to soften as a result of increased water content and collagen lysis. Simultaneous effacement, or thinning of the cervix, occurs as it is taken up into the lower uterine segment (Figure 8-8B). Consequently, patients often present in early labor with a cervix that is already partially effaced. As a result of cervical effacement, the mucous plug within the cervical canal may be released. The onset of labor may thus be heralded by the passage of a small amount of blood-tinged mucus from the vagina (“bloody show”).

STAGES OF LABOR

First Stage of Labor

PHASES

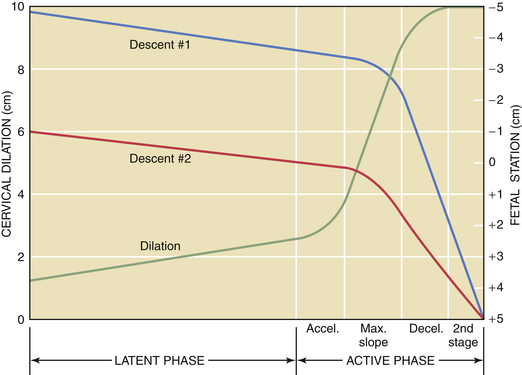

The first stage of labor consists of two phases: a latent phase, during which cervical effacement and early dilation occur, and an active phase, during which more rapid cervical dilation occurs (Figure 8-9). Although cervical softening and early effacement may occur before labor, during the first stage of labor, the entire cervical length is retracted into the lower uterine segment.

LENGTH

The length of the first stage may vary in relation to parity; primiparous patients generally experience a longer first stage than do multiparous patients (Table 8-2). Because the latent phase may overlap considerably with the preparatory phase of labor, its duration is highly variable. It may also be influenced by other factors, such as sedation and stress. The active phase begins when the cervix is 3 to 4 cm dilated in the presence of regularly occurring uterine contractions. The minimal dilation during the active phase of the first stage is nearly the same for primiparous and multiparous women: 1 and 1.2 cm/hour, respectively. If progress is slower than this, evaluation for uterine dysfunction, fetal malposition, or cephalopelvic disproportion should be undertaken.

| Characteristic | Primipara | Multipara |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of first stage | 6-18 hr | 2-10 hr |

| Rate of cervical dilation during active phase | 1 cm/hr | 1.2 cm/hr |

| Duration of second stage | 30 min to 3 hr | 5-30 min |

| Duration of third stage | 0-30 min | 0-30 min |

Second Stage of Labor

MECHANISM OF LABOR

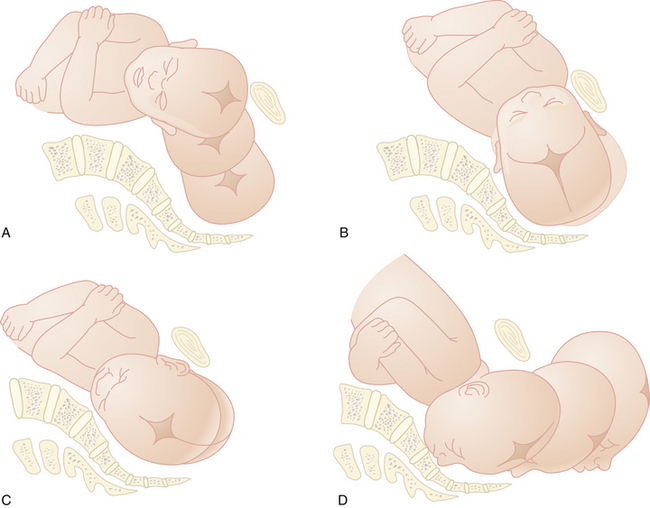

Six movements of the baby enable it to adapt to the maternal pelvis: descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion (Figure 8-10). These movements are discussed here for both an occipitoanterior and occipitoposterior position at engagement. The mechanism of labor for other presentations is discussed in Chapter 13.

FLEXION

Partial flexion exists before labor as a result of the natural muscle tone of the fetus. During descent, resistance from the cervix, walls of the pelvis, and pelvic floor cause further flexion of the cervical spine, with the baby’s chin approaching its chest. In the occipitoanterior position, the effect of flexion is to change the presenting diameter from the occipitofrontal to the smaller suboccipitobregmatic (see Figure 8-2). In the occipitoposterior position, complete flexion may not occur, resulting in a larger presenting diameter, which may contribute to a longer labor.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF THE SECOND STAGE

DELIVERY OF THE FETUS

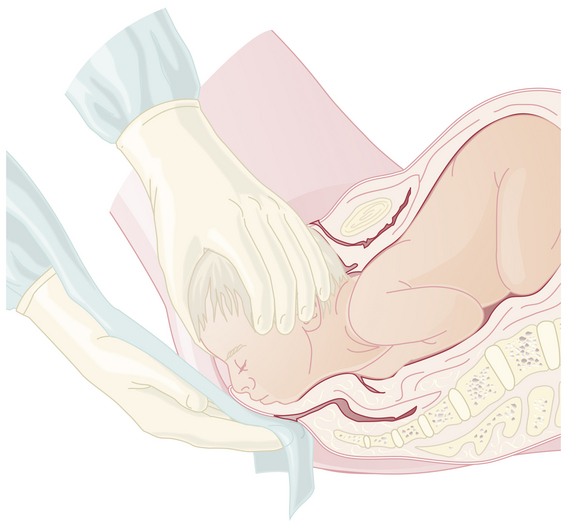

To facilitate delivery of the fetal head, a Ritgen maneuver may be performed (Figure 8-11). The right hand, draped with a towel, exerts upward pressure through the distended perineal body, first to the supraorbital ridges and then to the chin. This upward pressure, which increases extension of the head and prevents it from slipping back between contractions, is counteracted by downward pressure on the occiput with the left hand. A recent (2008) randomized trial from Sweden found simple manual perineal support to be equally effective.

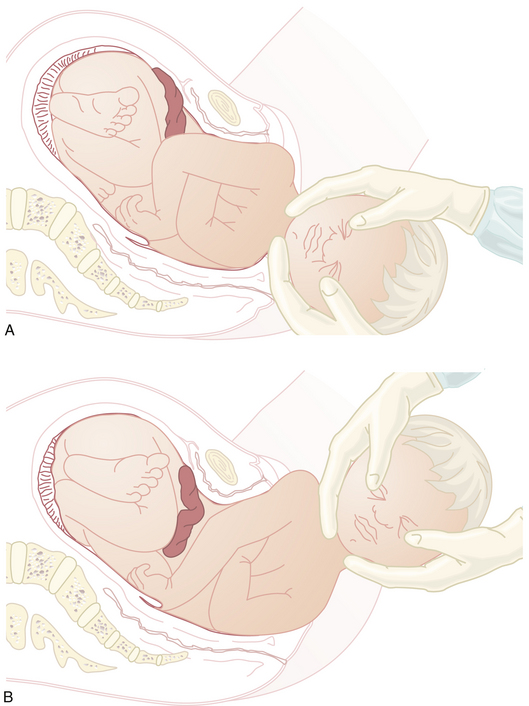

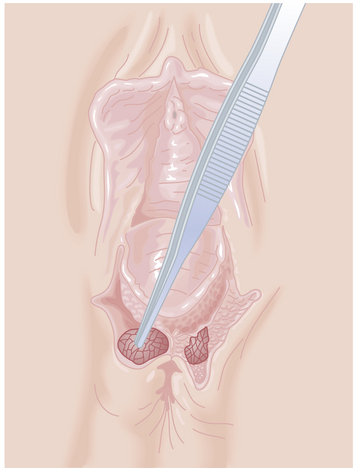

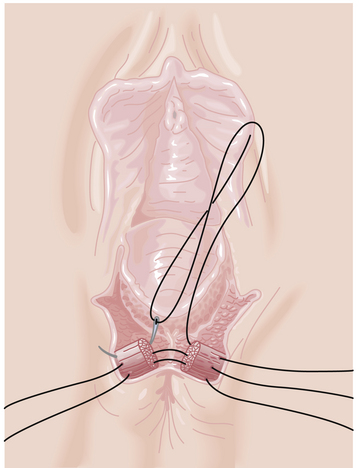

Following delivery of the head, the shoulders descend and rotate into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis and are delivered (Figure 8-12). Delivery of the anterior shoulder is aided by gentle downward traction on the externally rotated head. The brachial plexus may be injured if excessive force is used. The posterior shoulder is delivered by elevating the head. Finally, the body is slowly extracted by traction on the shoulders.

Third Stage of Labor

PERINEAL LACERATIONS

Perineal lacerations, with or without episiotomy, may be classified as follows:

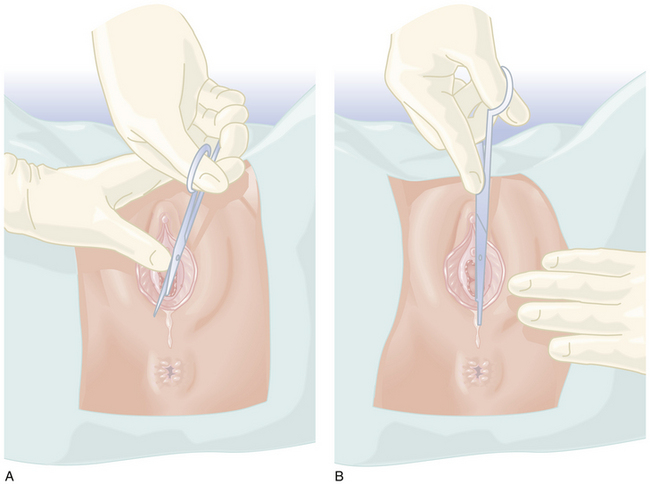

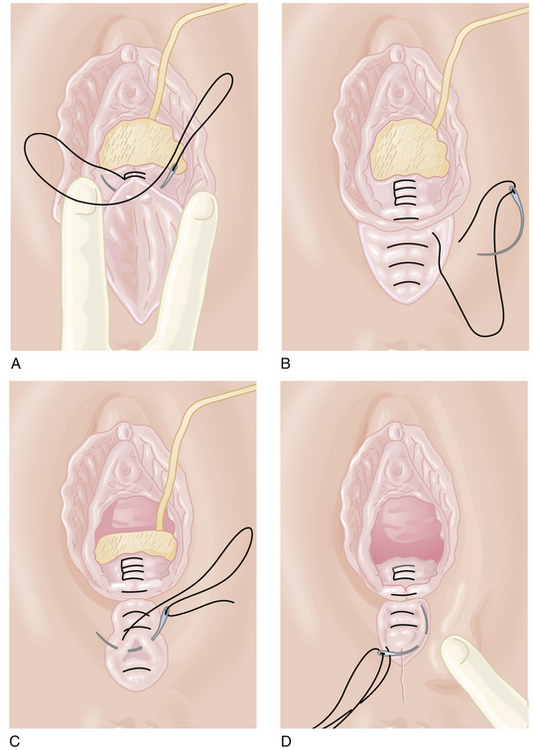

If an episiotomy has been performed (Figure 8-13),it should be repaired as illustrated in Figure 8-14Absorbable sutures (00) should be used, and a rectal examination should ensure that the sutures have not inadvertently transected the rectal mucosa. A third-degree tear (Figure 8-15) should be repaired as shown in Figure 8-16.

Induction and Augmentation of Labor

Induction and Augmentation of Labor

Other methods of cervical ripening may include intrauterine placement of catheters or the use of osmotic dilators (see Figure 26-4). Manual separation of the chorioamnion from the lower uterine segment does not necessarily speed the onset of labor. Although controversial, artificial rupture of the membranes may be used to increase uterine activity, and perhaps to speed cervical change, when performed in conjunction with administration of oxytocin.

In addition to cervical ripening, induction of labor requires the initiation of effective uterine contractions. Oxytocin is identical to the natural pituitary peptide, and it is the only drug approved for induction and augmentation of labor. Pitocin is the synthetic preparation. The physician must be fully aware of the indications and the contraindications for the use of oxytocin (Table 8-3). In general, induction of labor before term is indicated only when the continuation of pregnancy represents a significant risk to the fetus or mother. In some situations, induction may be indicated at term, as in the case of premature rupture of the membranes. Induction at term for convenience is not appropriate unless the patient has a history of previous precipitous delivery (less than 3 hours) or lives an unusually long distance from the hospital.

TABLE 8-3 INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR INDUCTION AND AUGMENTATION OF LABOR

| Induction | Augmentation |

|---|---|

| INDICATIONS | |

| Maternal | |

TECHNIQUE FOR INDUCTION AND AUGMENTATION OF LABOR

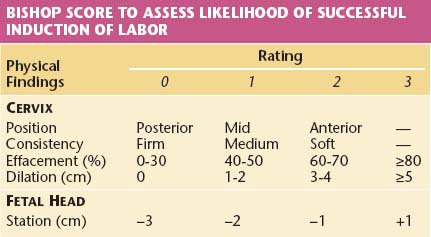

A hospital obstetric service must establish guidelines for the proper use of oxytocin for induction and augmentation of labor. In general, an assessment and plan of management must be outlined in the patient’s medical record. Indications for induction of labor should be clearly stated. It is helpful to assess the likelihood of success by a careful pelvic examination to determine the Bishop score, which evaluates the status of the cervix and the station of the fetal head (Table 8-4). A high score (9 to 13) is associated with a high likelihood of a vaginal delivery, whereas a low score (<5) is associated with a decreased likelihood of success (65% to 80%). Before induction is begun, the patient’s blood must be typed and screened for antibodies. A blood specimen should be held in the laboratory in case crossmatching becomes necessary. Continuous electronic monitoring of the fetal heart rate and uterine activity is required during induction. An internal uterine catheter for monitoring uterine pressure is suggested if intensity cannot be adequately assessed.

Oxytocin Infusion

Several principles should be followed when oxytocin is used to induce or augment labor:

Substantial variation exists regarding the initial dose, incremental dose, and time interval between dose increments when oxytocin is used for labor induction and augmentation. Well-performed clinical studies have supported both low-dose (1 to 30 mU/min) and high-dose (4 to 40 mU/min) protocols, as seen in Table 8-5It is not surprising that many protocols use “moderate” doses of oxytocin. Generally, intervals between dose increments should be no less than 20 minutes to permit time for steady-state plasma levels of oxytocin to be achieved and to prevent an increased risk for uterine hyperstimulation.

TABLE 8-5 METHOD OF OXYTOCIN INFUSION FOR INDUCTION OR AUGMENTATION

| SOLUTION | ||

| 10 units of oxytocin in 1000 mL of 5% dextrose or balanced salt solution (10 mU/mL) | ||

| ADMINISTRATION | ||

| Piggyback into main IV line; administer solution by infusion pump | ||

| Low-Dose Protocol | High-Dose Protocol | |

| Starting dose | 1 mU/min | 4 mU/min |

| Increment | 1 mU/min | 4 mU/min |

| Interval | 20 min | 20 min |

| Limited by | 5 contractions in 10 min | 7 contractions in 15 min |

| Maximal dose | 20-30 mU/min | 40 mU/min |

Puerperium

Puerperium

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding

COMPLICATIONS OF BREASTFEEDING

Drug Passage to the Newborn

Because an infant may ingest up to 500 mL of breast milk per day, maternally administered drugs that pass into breast milk may have a significant effect on the infant. The amount of drug found in breast milk depends on the maternal dose, the rate of maternal clearance, the physicochemical properties of the drug, and the composition of the breast milk with respect to fat and protein. The gestational age of the infant may also be a determinant of the ultimate drug effect. Table 8-6 lists selected drugs with their reported newborn effects.

TABLE 8-6 EFFECTS OF MATERNAL DRUG INGESTION ON BREASTFEEDING INFANTS

| Drug | Reported Infant Effects |

|---|---|

| SEDATIVE-HYPNOTICS | |

| Diazepam | Sedation |

| ANTIPSYCHOTICS | |

| Chlorpromazine | No adverse effects reported |

| Haloperidol | No adverse effects reported |

| NONNARCOTIC ANALGESICS | |

| Acetaminophen | No adverse effects reported |

| Salicylates | Theoretical risk for platelet dysfunction |

| ANTICONVULSANTS∗ | |

| Phenobarbital | Sedation |

| Phenytoin | Sedation, decreased sucking |

| NARCOTICS | |

| Heroin | May cause addiction |

| Methadone | Infant death reported |

| Meperidine | No adverse effects reported |

| ANTIBIOTICS | |

| Penicillin | May modify bowel flora, cause allergy, or interfere with sepsis work-up |

| Ampicillin | Same as for penicillin |

| Erythromycin | Same as for penicillin |

| Nitrofurantoin | Theoretical risk for hemolytic anemia in infants with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

| Tetracycline | Same as for penicillin; theoretical risk for discoloration of teeth and inhibition of bone growth |

| DIGOXIN | No adverse effects reported |

| THYROID DRUGS | |

| Thyroxine | May interfere with screening for hypothyroidism |

| Propylthiouracil | Nodular goiter |

| ANTIHYPERTENSIVES | |

| Methyldopa | No adverse effects reported |

| Propranolol | No adverse effects reported |

| THEOPHYLLINE | One case of infant irritability following maternal administration of a rapidly absorbed oral preparation |

∗ See Chapters 7 and 16.

Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia

Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia

ANESTHESIA FOR CESAREAN DELIVERY

The type of anesthesia selected for cesarean delivery is determined by the urgency of the surgery, the presence or absence of a preexisting epidural catheter for labor, and the patient’s medical condition, pregnancy-related complications, and presence of any contraindications to regional anesthesia. Absolute and relative contraindications to regional anesthesia are listed in Box 8-1All patients requiring anesthesia for surgery must have an airway examination regardless of how urgent the surgery is. A brief history must also be elicited. If the history or the physical examination suggests that the intubation will be difficult (Box 8-2), the patient must have a regional anesthetic or an awake intubation, or the operation must be started under local anesthesia.

For elective or urgent cesarean delivery (nonemergency), regional anesthesia is preferred because the airway is maintainedComplications involving loss of the airway are the leading causes of anesthetic-related maternal mortality and are usually associated with general anesthesia. General anesthesia carries a 16-fold higher risk of anesthesia-related maternal mortality compared with regional anesthesia (Table 8-7). Parturients have a higher risk for airway complications than nonpregnant patients because they have (1) an 8 times higher chance of failed intubation, (2) a 60% increased oxygen consumption, (3) a decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) resulting in a lower oxygen store, and (4) an increased risk for aspiration.

TABLE 8-7 CAUSES OF ANESTHETIC-RELATED MATERNAL DEATHS IN THE UNITED STATES, 1979-1990

| Causes | Anesthesia Deaths (%) |

|---|---|

| Airway problems | |

| Aspiration | 23 |

| Induction, intubation problems | 12 |

| Inadequate ventilation | 12 |

| Respiratory failure | 2 |

| Local anesthetic toxicity | 13 |

| High spinal, epidural | 9 |

| Cardiac arrest | 23 |

| Overdosage | 1 |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 |

If no epidural is in place, a spinal block is frequently used. A comparison of the characteristics of spinal and epidural anesthesia is shown in Table 8-8.

TABLE 8-8 COMPARISON OF SPINAL AND EPIDURAL ANESTHESIA

| Spinal | Epidural |

|---|---|

| ADVANTAGES | |

| Faster | Can tailor duration to need |

| Technically easier | Lower chance of postdural puncture headache |

| More reliable | Slower onset |

| Defined end point | Beneficial in patients with cardiac and hypertensive disorders |

| Minimal chance of patchy block | |

PATIENTS WHO BENEFIT FROM EARLY ANESTHETIC CONSULTATION

Mothers who are at particularly high anesthetic risk should receive a prelabor consultation for significant preexisting medical conditions (e.g., difficult airway; see Box 8-2); significant respiratory, cardiac, or neurologic disease; spinal surgery; and suspected or known susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia.

Preparation for Extrauterine Life

Preparation for Extrauterine Life

Apgar Score

Apgar Score

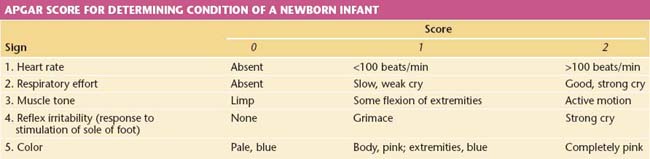

The Apgar score is an excellent tool for assessing the overall status of the newborn soon after birth (1 minute) and after a 5-minute period of observation (Table 8-9). A normal Apgar score is 7 or greater at 1 minute and 9 or 10 at 5 minutes.

Resuscitation of the Asphyxiated Infant

Resuscitation of the Asphyxiated Infant

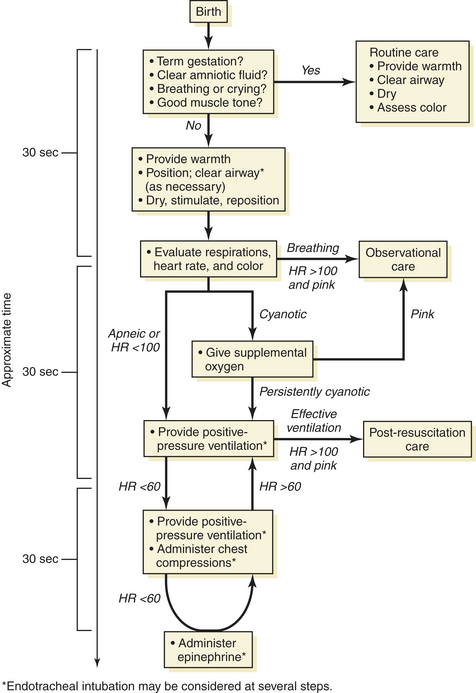

A stepwise sequence of procedures is necessary to enable a smooth transition to a normal metabolic state (Figure 8-18).

FIGURE 8-18 A time-based approach to the possible resuscitation of a normal and apneic or cyanotic newborn.

(Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics: Summary of Major Changes to the 2005 AAP/AHA Emergency Cardiovascular Care Guidelines for Neonatal Resuscitation: Translating Evidence-Based Guidelines to the NRP. Vol 15, No. 2, Fall/Winter 2005.)

4 CORRECT BIOCHEMICAL ABNORMALITIES

Narcotic Depression

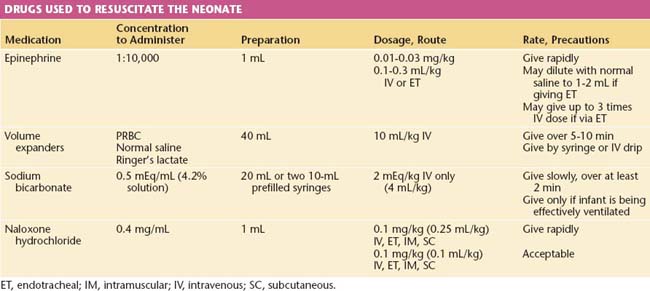

Respiratory depression secondary to medication is unusual with the increased use of conduction anesthesia. If neonatal respiratory depression from excessive use of narcotics is suspected, naloxone (Narcan) is an effective antidote. It is just as effective and more easily administered intramuscularly than intravenously. Table 8-10 lists the drugs that are commonly used in resuscitation and their dosages.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 36: Obstetric anesthesia and analgesia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:177-191.

American Society of Anesthesiologists: Practical guidelines for obstetrical anesthesia. Amended October 18, 2006. Available at: http:www.asahq.org/publicationsandservices/Obguide.pdf.

Hawkins J.L., Kooin L.M., Palmer S.K., Gibbs C.P. Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States 1979-1990. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:277-284.

Jönsson E.R., Elfaghi I., Rydhström H., Herbst A. Modified Ritgen’s maneuver for anal sphincter injury at delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:212-217.

2005 AAP/AHA Guidelines for Neonatal Resuscitation. Available at: http://www.C2005.org.

Interconception Care

Interconception Care

Resuscitation of the Newborn

Resuscitation of the Newborn