Normal child development, hearing and vision

Normal development in the first few years of life is monitored:

• by parents, who are provided with guidance about normal development in their child’s personal child health record and in a book Birth to Five, given to all parents in the UK

• at regular child health surveillance checks

• whenever a young child is seen by a healthcare professional, when a brief opportunistic overview is made.

• help children achieve their maximum potential

• provide treatment or therapy promptly (particularly important for impairment of hearing and vision)

• act as an entry point for the care and management of the child with special needs.

This chapter covers normal development. Delayed or abnormal development and the child with special needs are considered in Chapter 4.

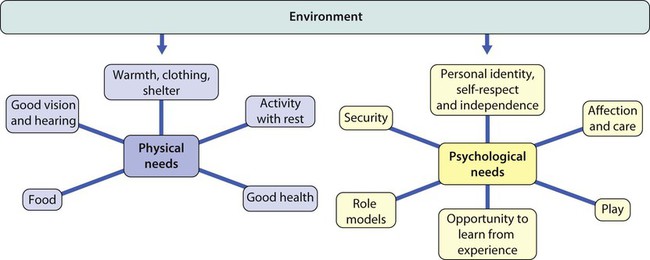

Influence of heredity and environment

A child’s development represents the interaction of heredity and the environment on the developing brain. Heredity determines the potential of the child, while the environment influences the extent to which that potential is achieved. For optimal development, the environment has to meet the child’s physical and psychological needs (Fig. 3.1). These vary with age and stage of development:

• Infants are totally physically dependent on their parents and require a limited number of carers to meet their psychological needs.

• Primary school-age children can meet some of their physical needs and cope with many social relationships.

• Adolescents are able to meet most of their physical needs while experiencing increasingly complex emotional needs.

Developmental milestones

When considering developmental milestones:

• The median age is the age when half of a standard population of children achieve that level; it serves as a guide to when stages of development are likely to be reached but does not tell us if the child’s skills are outside the normal range.

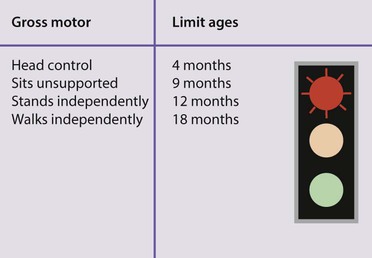

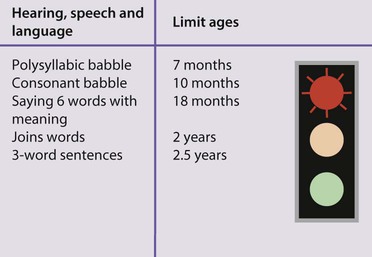

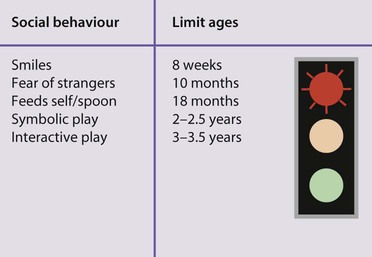

• Limit ages are the age by which they should have been achieved. Limit ages are usually 2 standard deviations (SD) from the mean. They are more useful as a guide to whether a child’s development is normal than the median ages. Failure to meet them gives guidance for action regarding more detailed assessment, investigation or intervention.

Variation in the pattern of development

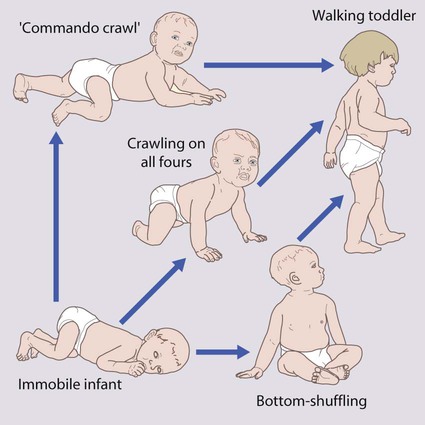

There is variation in the pattern of development between children. Taking motor development as an example, normal motor development is the progression from immobility to walking, but not all children do so in the same way. While most achieve mobility by crawling (83%), some bottom-shuffle and others crawl with their abdomen on the floor, so-called commando crawling (creeping) (Fig. 3.3). A very few just stand up and walk. The locomotor pattern (crawling, creeping, shuffling, just standing up) determines the age of sitting, standing and walking.

Is development normal?

When evaluating a child’s developmental progress and considering whether it is normal or not:

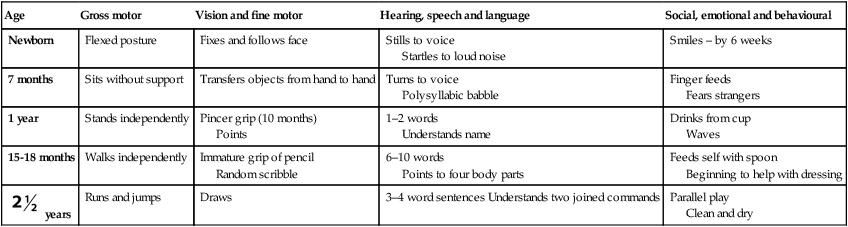

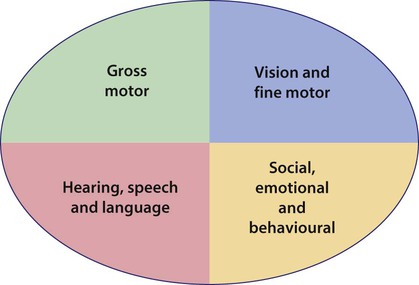

• Concentrate on each field of development (gross motor; vision and fine motor; hearing, speech and language; social, emotional and behavioural) separately.

• Consider the developmental pattern by thinking longitudinally and separately about each developmental field. Ask about the sequence of skills achieved as well as those skills to be anticipated shortly.

• Determine the level the child has reached for each skill field.

• Now relate the progress of each developmental field to the others. Is the child progressing at a similar rate through each skill field, or does one or more field of development lag behind the others?

• Then relate the child’s developmental achievements to age (chronological or corrected).

Pattern of child development

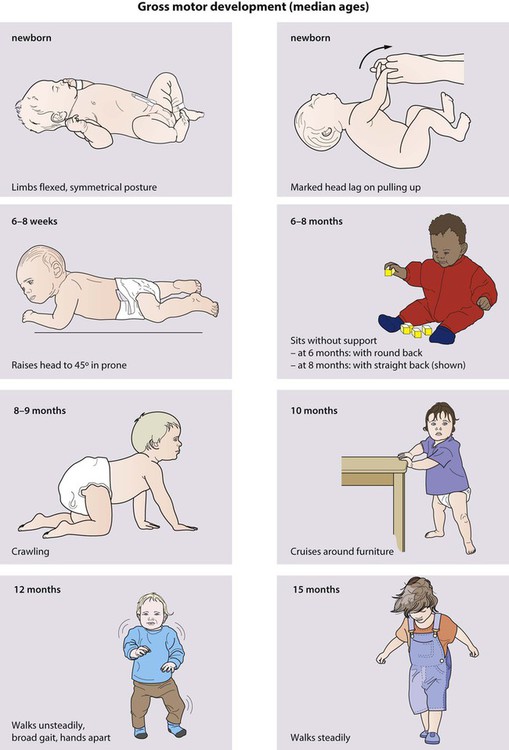

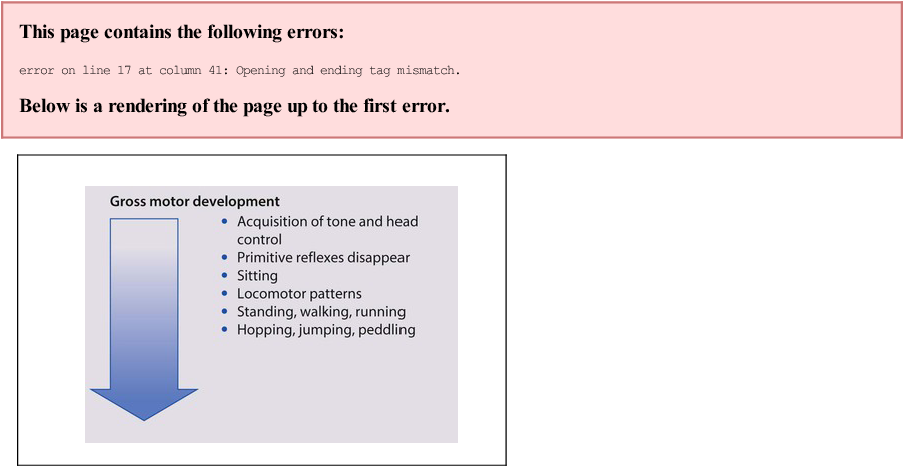

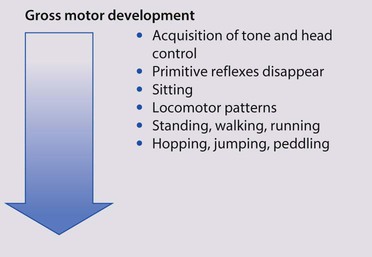

• Gross motor development (Fig. 3.4 and Table 3.1)

Table 3.1

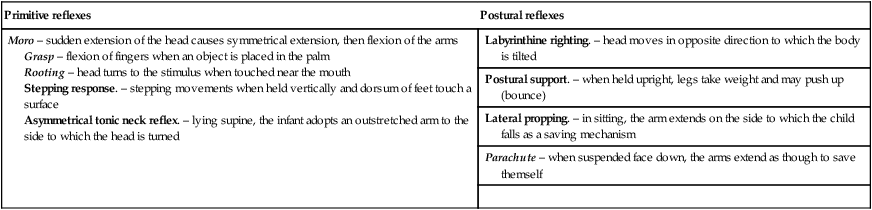

| Primitive reflexes | Postural reflexes |

| Moro – sudden extension of the head causes symmetrical extension, then flexion of the arms Grasp – flexion of fingers when an object is placed in the palm Rooting – head turns to the stimulus when touched near the mouth Stepping response. – stepping movements when held vertically and dorsum of feet touch a surface Asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. – lying supine, the infant adopts an outstretched arm to the side to which the head is turned |

Labyrinthine righting. – head moves in opposite direction to which the body is tilted |

| Postural support. – when held upright, legs take weight and may push up (bounce) | |

| Lateral propping. – in sitting, the arm extends on the side to which the child falls as a saving mechanism | |

| Parachute – when suspended face down, the arms extend as though to save themself | |

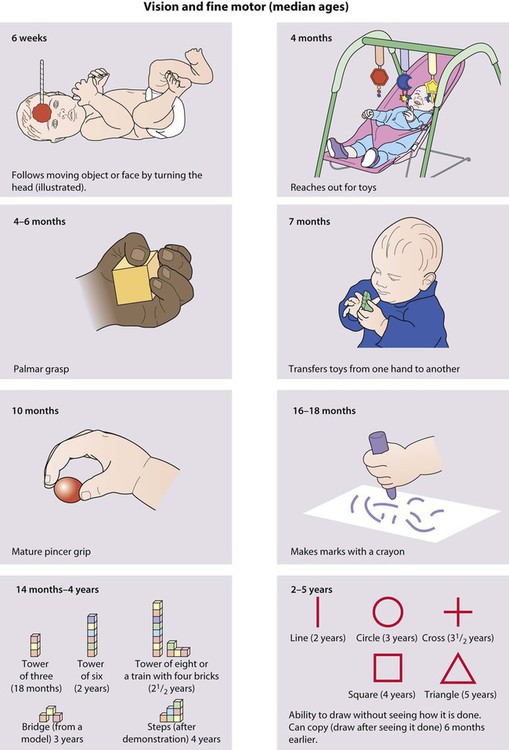

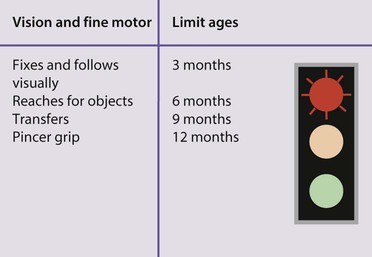

• Vision and fine motor (Fig. 3.5)

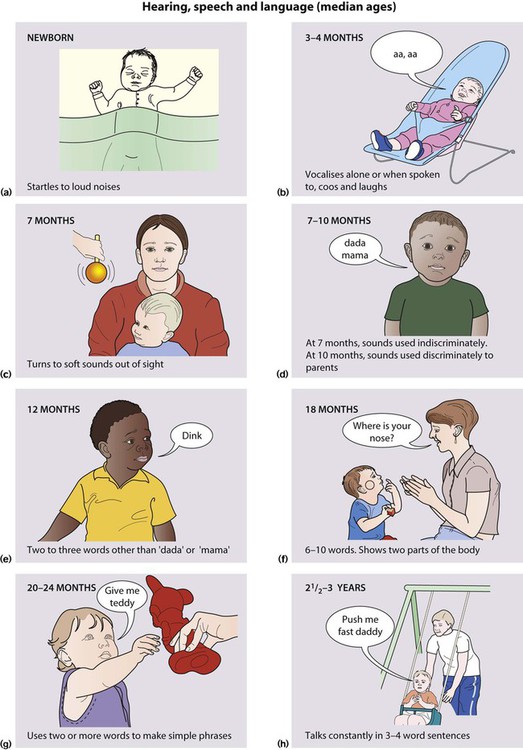

• Hearing, speech and language (Fig. 3.6)

Cognitive development

• they are the centre of the world

• inanimate objects are alive and have feelings and motives

• events have a magical element

• everything has a purpose. Toys and other objects are used in imaginative play as aids to thought, to help make sense of experience and social relationships.

Analysing developmental progress

The short-cut approach

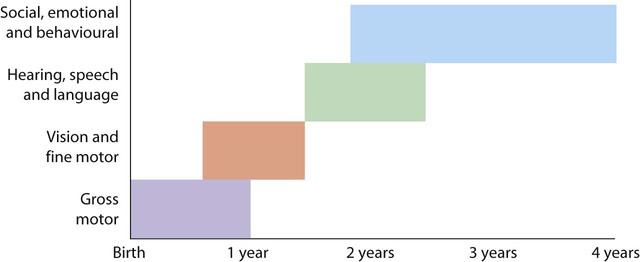

This concentrates on the most actively changing skills for the child’s age. The age at which developmental progress accelerates differs in each of the developmental fields. Figure 3.8 demonstrates the age when there is the most rapid emergence of skills in each developmental field. This means there is for:

• gross motor development: an explosion of skills during the first year of life

• vision and fine motor development: more evident acquisition of skills from 1 year onwards

• hearing, speech and language: a big expansion of skills from 18 months

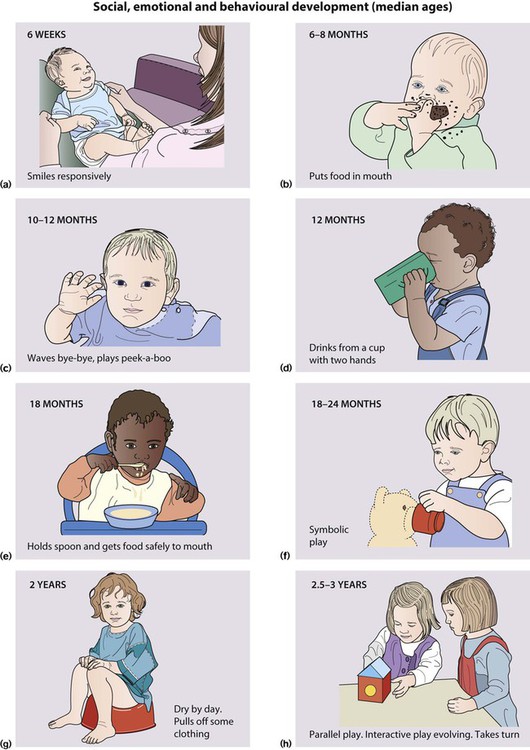

• social, emotional and behavioural development: expansion in skills is most obvious from 2.5 years.

• <18 months – it is likely to be most useful to begin questions around gross motor abilities, acquisition of vision and hearing skills, followed by questions about hand skills.

• 18 months to 2.5 years – initial developmental questioning is likely to be most usefully directed at acquisition of speech and language and fine motor (hand) skills with only later and brief questioning about gross motor skills (as it is likely the child would have presented earlier if these were of concern).

• 2.5 to 3.5 years – initial questions are best focused around speech and language and social, emotional and behaviour development.

Developmental screening and assessment

There are a number of problems inherent in developmental screening:

• It is a subjective clinical opinion, and therefore has its limitations

• A single observation of development may be limited by the child being tired, hungry, shy or simply not wishing to take part

• While much of the focus of early developmental progress in infants is centred on motor development, this is a poor predictor of problems in cognitive function and later school performance. Development of speech and language is a better predictor of cognitive function but is less easy to assess rapidly and may come at a time of less contact with health professionals.

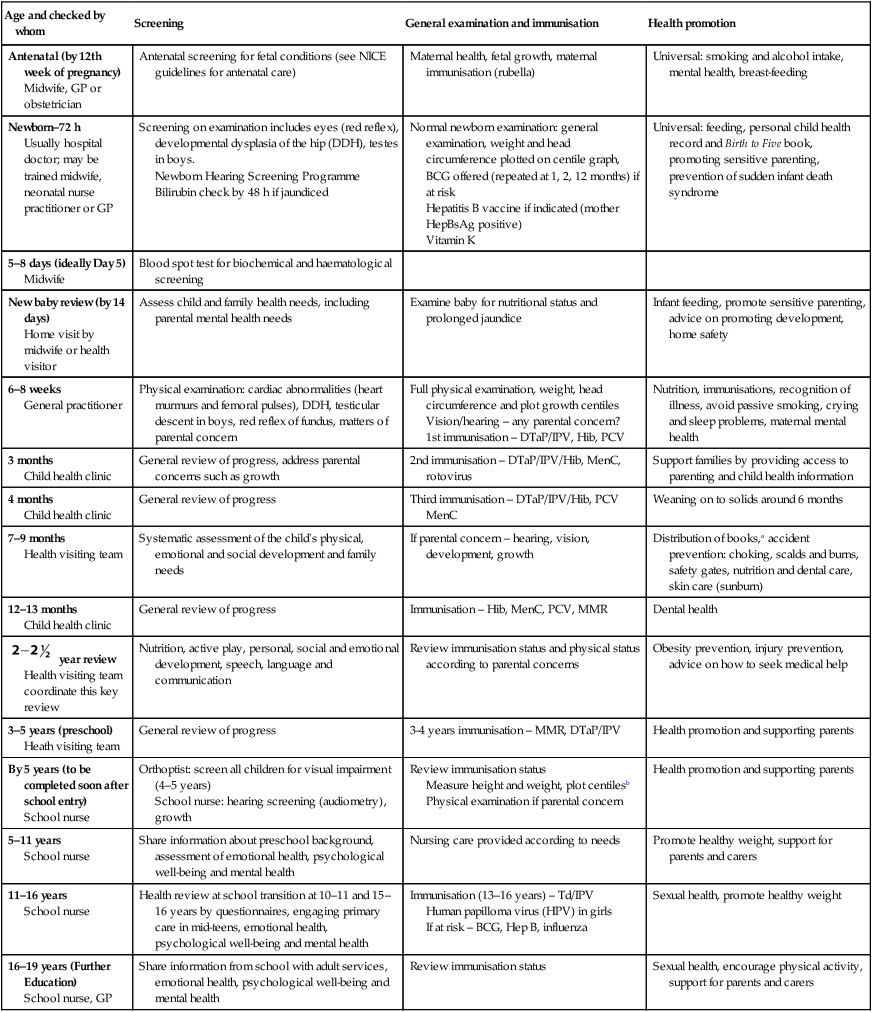

Child health surveillance

It offers families a programme of:

• Screening tests – early detection

• Immunisation – disease prevention

• Developmental reviews – including a specific screening at 2 years, an age when less obvious areas of developmental concern may arise with language skills

• Health promotion – information and guidance to support parenting and healthy choices.

There is a ‘universal’ programme, and a ‘progressive’ programme for families thought to be more at risk. Those in the progressive programme include infants or children with health or developmental problems, children at increased risk of obesity or families considered to be at higher risk, e.g. at-risk first-time mothers; parents with learning difficulties, drug or alcohol abuse or serious mental illness, insensitive (i.e. intrusive or passive) parenting interactions or domestic violence. These families receive additional intervention according to need. The programme is a compromise between the desire to detect problems and provide early intervention for all, while avoiding an excessive number of assessments. The way the healthy child programme (HCP) is organised is shown in Table 3.2. At each review, a check is made for specific physical abnormalities and on the child’s overall development, health and growth. Selected health promotion topics are considered. There is an emphasis on parental opinion for vision, hearing, speech and language, as parents are usually excellent at the early detection of these problems. Details of each review are entered into the child’s personal child health record kept by parents and brought whenever the child is seen by a health professional.

Table 3.2

| Age and checked by whom | Screening | General examination and immunisation | Health promotion |

| Antenatal (by 12th week of pregnancy) Midwife, GP or obstetrician |

Antenatal screening for fetal conditions (see NICE guidelines for antenatal care) | Maternal health, fetal growth, maternal immunisation (rubella) | Universal: smoking and alcohol intake, mental health, breast-feeding |

| Newborn–72 h Usually hospital doctor; may be trained midwife, neonatal nurse practitioner or GP |

Screening on examination includes eyes (red reflex), developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), testes in boys. Newborn Hearing Screening Programme Bilirubin check by 48 h if jaundiced |

Normal newborn examination: general examination, weight and head circumference plotted on centile graph, BCG offered (repeated at 1, 2, 12 months) if at risk Hepatitis B vaccine if indicated (mother HepBsAg positive) Vitamin K |

Universal: feeding, personal child health record and Birth to Five book, promoting sensitive parenting, prevention of sudden infant death syndrome |

| 5–8 days (ideally Day 5) Midwife |

Blood spot test for biochemical and haematological screening | ||

| New baby review (by 14 days) Home visit by midwife or health visitor |

Assess child and family health needs, including parental mental health needs | Examine baby for nutritional status and prolonged jaundice | Infant feeding, promote sensitive parenting, advice on promoting development, home safety |

| 6–8 weeks General practitioner |

Physical examination: cardiac abnormalities (heart murmurs and femoral pulses), DDH, testicular descent in boys, red reflex of fundus, matters of parental concern | Full physical examination, weight, head circumference and plot growth centiles Vision/hearing – any parental concern? 1st immunisation – DTaP/IPV, Hib, PCV |

Nutrition, immunisations, recognition of illness, avoid passive smoking, crying and sleep problems, maternal mental health |

| 3 months Child health clinic |

General review of progress, address parental concerns such as growth | 2nd immunisation – DTaP/IPV/Hib, MenC, rotovirus | Support families by providing access to parenting and child health information |

| 4 months Child health clinic |

General review of progress | Third immunisation – DTaP/IPV/Hib, PCV MenC | Weaning on to solids around 6 months |

| 7–9 months Health visiting team |

Systematic assessment of the child’s physical, emotional and social development and family needs | If parental concern – hearing, vision, development, growth | Distribution of books,a accident prevention: choking, scalds and burns, safety gates, nutrition and dental care, skin care (sunburn) |

| 12–13 months Child health clinic |

General review of progress | Immunisation – Hib, MenC, PCV, MMR | Dental health |

year review year reviewHealth visiting team coordinate this key review |

Nutrition, active play, personal, social and emotional development, speech, language and communication | Review immunisation status and physical status according to parental concerns | Obesity prevention, injury prevention, advice on how to seek medical help |

| 3–5 years (preschool) Heath visiting team |

General review of progress | 3-4 years immunisation – MMR, DTaP/IPV | Health promotion and supporting parents |

| By 5 years (to be completed soon after school entry) School nurse |

Orthoptist: screen all children for visual impairment (4–5 years) School nurse: hearing screening (audiometry), growth |

Review immunisation status Measure height and weight, plot centilesb Physical examination if parental concern |

Health promotion and supporting parents |

| 5–11 years School nurse |

Share information about preschool background, assessment of emotional health, psychological well-being and mental health | Nursing care provided according to needs | Promote healthy weight, support for parents and carers |

| 11–16 years School nurse |

Health review at school transition at 10–11 and 15–16 years by questionnaires, engaging primary care in mid-teens, emotional health, psychological well-being and mental health | Immunisation (13–16 years) – Td/IPV Human papilloma virus (HPV) in girls If at risk – BCG, Hep B, influenza |

Sexual health, promote healthy weight |

| 16–19 years (Further Education) School nurse, GP |

Share information from school with adult services, emotional health, psychological well-being and mental health | Review immunisation status | Sexual health, encourage physical activity, support for parents and carers |

DTaP/IPV: Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio immunization; Hib: Haemophilus B influenzae; PCV: Pneumococcal;

MenC: Meningitis C; Td/IPV: Diphtheria, tetanus, polio; MMR: Measles, Mumps and Rubella

aBookstart – national programme to encourage parents and carers to enjoy books with their children from an early age.

bThe national child measurement programme – height and weight of all reception and year 6 children.

Adapted from: The Healthy Child Programme 2009, Department of Health, London, UK.

Hearing

During the later stages of pregnancy, the fetus responds to sound. At birth, a baby startles to sound, but there is a marked preference for voices. The ability to locate and turn towards sounds comes later in the first year. A checklist for parents of normal hearing responses during infancy is shown in Box 3.1.

Hearing tests

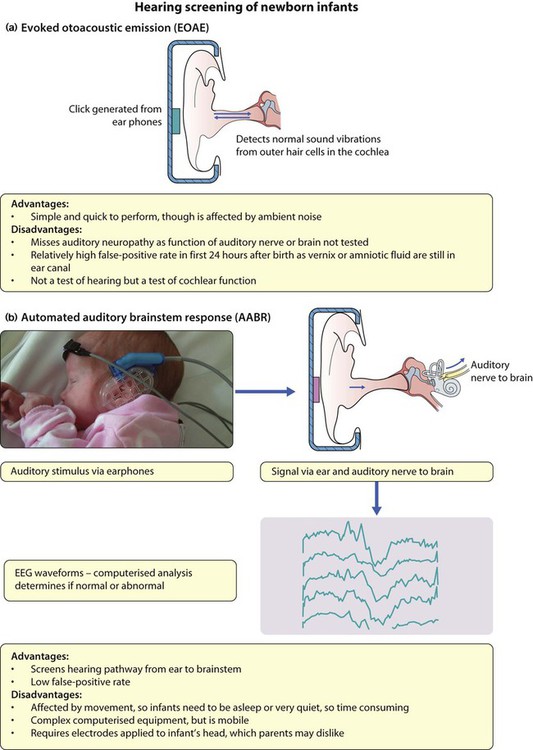

Newborn

• Evoked otoacoustic emission (EOAE) (Fig. 3.9a) – an earphone produces a sound which evokes an echo or emission from the ear if cochlear function is normal.

• Auditory brainstem response (ABR) audiometry (Fig. 3.9b) – computer analysis of EEG waveforms evoked in response to a series of auditory stimuli.

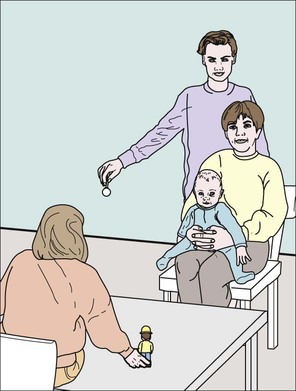

Distraction testing

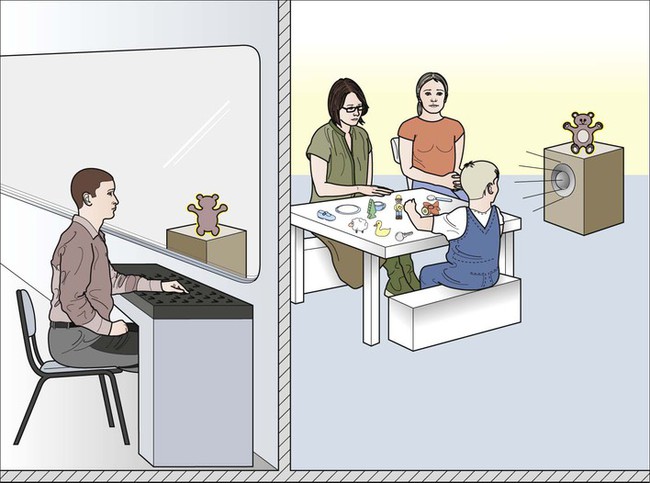

This was the mainstay of hearing screening but has been replaced by universal neonatal screening. It is now only used as a screening test for infants who have not had newborn screening or as a diagnostic test. It is performed at 7–9 months of age (Fig. 3.10). The test relies on the baby locating and turning appropriately towards sounds. High- and low-frequency sounds are presented out of the infant’s field of vision. Testing is unreliable if not carried out by properly trained staff, since it can be difficult to identify hearing-impaired infants as they are particularly adept at using non-auditory cues.

Visual reinforcement audiometry

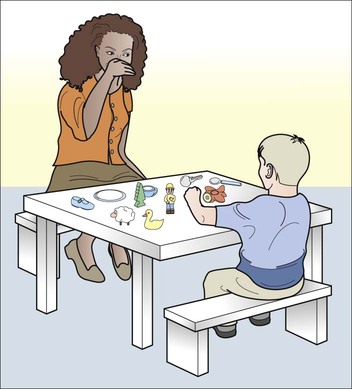

This is particularly useful to assess impairment in infants between 10 and 18 months, although it can be used between the age of 6 months and 3 years. Hearing thresholds are established using visual rewards (illumination of toys) to reinforce the child’s head turn to stimuli of different frequencies. Localisation of the stimuli is not necessary and insert earphones may be used to obtain ear-specific information, thus making it more useful than free field tests such as distraction and performance testing (Fig. 3.11).

Vision

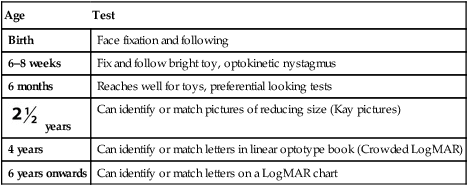

Vision testing

The assessment of vision at different ages is shown in Table 3.3. All children in the UK are screened for visual acuity and squint at school entry. In some parts of the UK, screening is carried out in preschool children at 4–5 years.

Table 3.3

Testing vision at different ages

| Age | Test |

| Birth | Face fixation and following |

| 6–8 weeks | Fix and follow bright toy, optokinetic nystagmus |

| 6 months | Reaches well for toys, preferential looking tests |

years years |

Can identify or match pictures of reducing size (Kay pictures) |

| 4 years | Can identify or match letters in linear optotype book (Crowded LogMAR) |

| 6 years onwards | Can identify or match letters on a LogMAR chart |

Note: Using single letters/pictures instead of lines underestimates amblyopia severity (see Ch. 4).

years

years