Chapter 30 Noninfectious Conditions in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Although most complications affecting the lungs during the course of HIV infection arise from the viral infection itself, especially as reported early in the epidemic, HIV-infected patients may present with or subsequently develop complications related to alterations in immune regulation. A marked CD8+ T cell infiltrate in the lung may be caused by HIV in both symptomatic and nonsymptomatic patients. The effects of the virus on the pulmonary microenvironment include a progressive decline in local immunocompetence that results in failure to mount a protective immune response against opportunistic infections. The spectrum of noninfectious complications associated with HIV infection encompasses other idiopathic conditions and pulmonary malignancies, which include Kaposi sarcoma, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and solid tumors (Table 30-1 and 30-2).

Table 30-1 Noninfectious Pulmonary Conditions Associated With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection

| Disease Category | Specific Disease(s) |

|---|---|

| Neoplastic disease | |

| Inflammatory disease | |

| Airway disease | |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | Pulmonary hypertension |

| Miscellaneous | Antiretroviral treatment–induced respiratory disease |

Table 30-2 Association of Noninfectious Pulmonary Conditions with Degree of Immunodeficiency

| Degree of Immunodeficiency | Noninfectious Pulmonary Condition |

|---|---|

| Severe (CD4+ cell count less than 50 cells/µL) | |

| Moderate to severe (CD4+ cell count 50-200 cells/µL) | |

| Moderate (CD4+ cell count 200-350 cells/µL) | |

| Normal (CD4+ cell count greater than 350 cells/µL) |

Neoplasia

Kaposi Sarcoma

Clinical Features

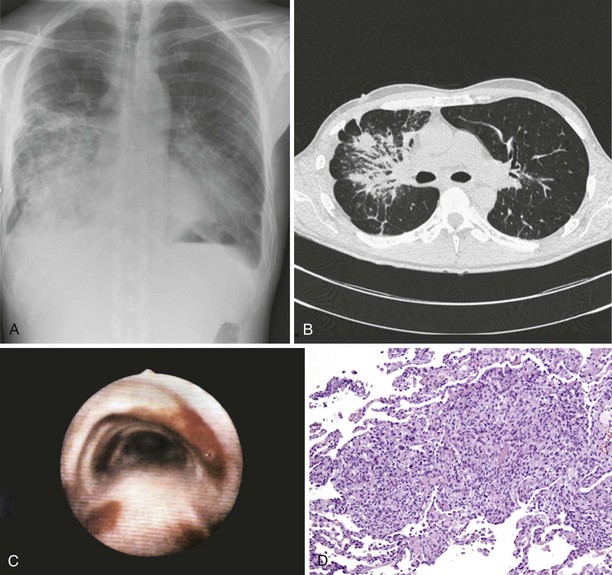

Pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma may cause nonproductive cough, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, chest pain, and fever. In rare instances, involvement of the larynx or trachea may cause airway obstruction. Extrapulmonary involvement is frequent, but 15% of cases of Kaposi sarcoma occur without skin lesions. CD4+ cell counts are low (0 to 100/µL) at the time of diagnosis. Examination of the lungs usually shows no abnormalities. Chest radiograph may be normal in appearance but commonly shows singular or multiple peribronchovascular nodules (Figure 30-1, A and B). Diffuse infiltration and air space consolidation also may be present. Pleural effusion is common. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy may be visible on chest films but are better visualized with computed tomography (CT) scanning. With pulmonary disease, CT scans typically reveal peribronchovascular nodules that are larger than 1 cm in diameter. The role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma is not clear.

Diagnosis

Pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma is highly likely in a HIV-1–infected person with a CD4+ cell count of less than 100/µL, the characteristic cutaneous or mucocutaneous lesions, and pulmonary symptoms. Bronchoscopy is useful to visualize typical endobronchial lesions (see Figure 30-1, C). These are flat or slightly raised and occur throughout the tracheobronchial tree but are seen most frequently at airway bifurcations. Pleural effusions usually are exudative and may be serous or serosanguineous. Serum lactate dehydrogenase may be elevated. Histologic verification is usually not required for a diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Endobronchial biopsy may confer a substantial risk of severe bleeding, but biopsy may be necessary in cases in which bronchial involvement is lacking. In such cases, transbronchial or percutaneous needle biopsy is useful. In cases of pleural Kaposi sarcoma, video-assisted thoracoscopy can be used to visualize pleural lesions and to perform biopsy. Open lung biopsy in this setting is obsolete because of the associated complications. Lung biopsy specimens show typical features of Kaposi sarcoma, which include a tumor-like infiltrate with a peribronchovascular distribution of spindle cells. Slitlike spaces without endothelium contain extravasated erythrocytes (see Figure 30-1, D). In situ hybridization and immunostaining usually are positive for HHV-8. HHV-8 DNA is detectable in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) cells.

Treatment

Investigational agents include thalidomide, imatinib, mTOR inhibitors, IL-12, and fumagilin.

Multicentric Castleman Disease

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Clinical Features

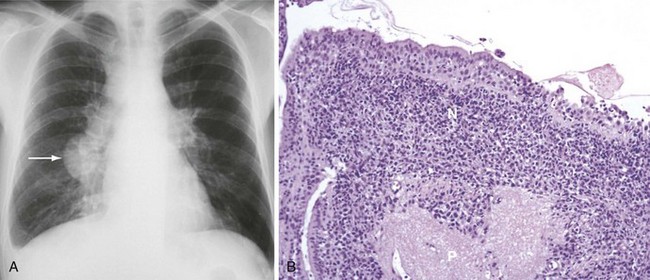

Patients may present with nodal or extranodal disease and may have systemic symptoms. Clinical signs of advanced NHL with pulmonary involvement include fever, night sweats, and weight loss (B symptoms). Manifestations of primary pulmonary involvement include shortness of breath, cough, and chest pain. Primary pulmonary lymphoma is associated with CD4+ cell counts less than 50/µL. Anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia are frequent findings. Serum lactate dehydrogenase often is elevated with secondary but not primary pulmonary involvement. Chest radiographs and CT scans commonly show isolated or multiple central or peripheral nodules (Figure 30-2, A). Mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pleural effusion are less common.

Diagnosis

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy usually is normal. Cytologic examination of BAL fluid may reveal lymphoma cells, but biopsy is required to establish a histologic diagnosis. Transbronchial biopsy has reasonable diagnostic yield for secondary but not primary pulmonary lymphoma. Percutaneous thoracic needle biopsy is the most commonly used method to obtain tissue for diagnosis. In rare cases, video-assisted thoracoscopic or open lung biopsy may be necessary. Histologically, the lymphoma invades the alveolar septa and vascular walls (see Figure 30-2, B). Necrosis is frequent. Most tumors are high-grade centroblastic or immunoblastic large B cell lymphomas that are EBV-positive and overexpress Bcl-2.

Primary Effusion Lymphoma

Inflammatory Pulmonary Disorders

Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonitis

Clinical Features

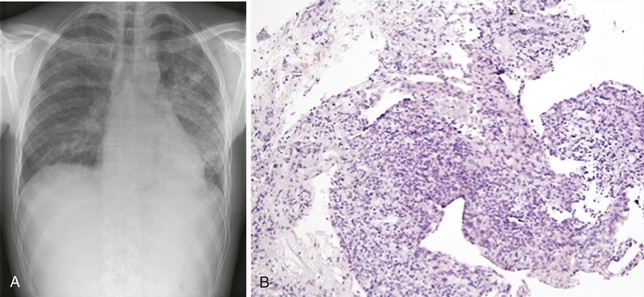

The signs and symptoms of NIP are unspecific and resemble many clinical manifestations of HIV-1 infection such as cough, shortness of breath, and fever. Extrapulmonary involvement is rare. Examination of the lungs usually yields normal findings. There may be subtle hypoxia that further increases on exercise. Chest radiographs and CT scans may be normal in appearance or show diffuse alveolar, nodular, or interstitial infiltrates that are indistinguishable from those typically seen in other common HIV-1–associated infections (Figure 30-3, A). Pleural effusion is less common.

Diagnosis

Suspicion of NIP should arise when standard histocytologic studies, microbiologic staining and culture, and molecular techniques do not yield a pathogen. Thus, NIP is a diagnosis of exclusion. Tissue specimens are required to establish the diagnosis and may be obtained by bronchoscopy, fine needle aspiration, or open lung biopsy procedures. Transbronchial biopsy specimens characteristically show various degrees of perivascular, peribronchial, and pleural lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration. Edema, fibrin deposition, pneumocyte hyperplasia, and thickening of alveolar septa are common; alveolar septal infiltration is uncommon (see Figure 30-3, B). Lymphoid aggregates are frequently seen. BAL fluid analysis shows lymphocytosis and a decrease in relative and absolute numbers of alveolar macrophages. Because of the risks involved with biopsy procedures, some clinicians make a presumptive diagnosis after ruling out an infectious cause for the patient’s pulmonary symptoms.

Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonitis

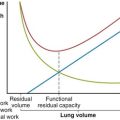

Chronic Airway Disease and Emphysema

Genetics

Mutations in the α1-antitrypsin gene predispose affected persons to the development of emphysema.

Miscellaneous Conditions

Aboulafia DM. The epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features of AIDS-associated pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma. Chest. 2000;117:1128–1145.

Bower M, Collins S, Cottrill C, et al. British HIV Association guidelines for HIV-associated malignancies 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9:336–388.

Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, et al. HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:388–395.

Gingo MR, George MP, Kessinger CJ, et al. Pulmonary function abnormalities in HIV-infected patients during the current antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:790–796.

Grubb JR, Moorman AC, Baker RK, Masur H. The changing spectrum of pulmonary disease in patients with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20:1095–1107.

Guiguet M, Boué F, Cadranel J, et al. Effect of immunodeficiency, HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy on the risk of individual malignancies (FHDH-ANRS CO4): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1152–1159.

Guihot A, Couderc LJ, Rivaud E, et al. Thoracic radiographic and CT findings of multicentric Castleman disease in HIV-infected patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2007;22:207–211.

Rosen MJ, Beck JM. Human immunodeficiency virus and the lung. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998.

Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood. 1996;88:645–656.

Ray P, Antoine M, Mary-Krause M, et al. AIDS-related primary pulmonary lymphoma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1221–1229.

Sitbon O, Lascoux-Combe C, Delfraissy JF, et al. Prevalence of HIV-related pulmonary arterial hypertension in the current antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:108–113.