Chapter 26 Nonbacterial Infectious Pneumonia

Fungal Pneumonias

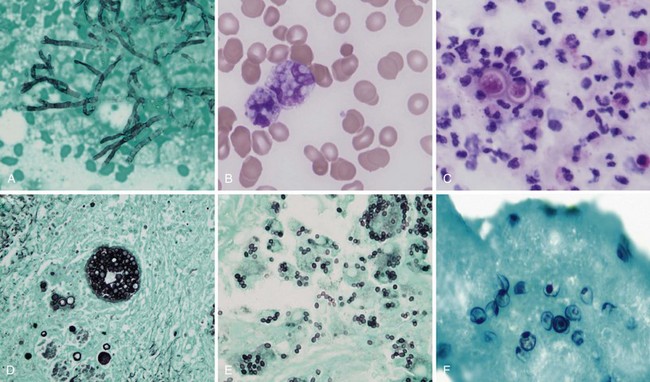

Aspergillosis

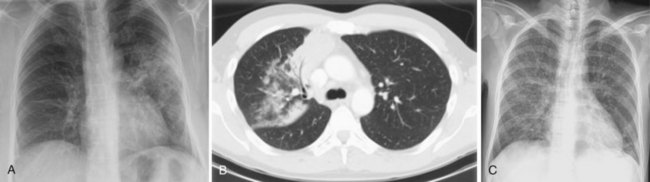

Aspergillus organisms are ubiquitous saprophytic fungi. They grow well in soil and decaying vegetation. These fungi also have been found in hospitals, ventilation and water systems, and dust associated with construction activity. Disease manifestations depend on the immune status and lung structure of the host. Clinical manifestations include allergic disease, airway colonization, aspergilloma formation, tracheobronchial disease, chronic necrotizing pneumonia, and invasive disseminating disease. Allergic disease generally is seen in immunocompetent patients and may encompass airway hyperreactivity, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Airway colonization occurs in patients with impaired mucociliary clearance or distorted lung structure such as in bronchiectasis. Aspergillomas, or “fungus balls,” thrive in cavitary lung lesions such as those associated with tuberculosis. Tracheobronchial aspergillosis and chronic necrotizing pneumonia (locally invasive aspergillosis) are manifestations found in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), recipients of transplanted organs (especially lungs), and patients with obstructive lung disease who use inhaled or systemic steroids. Finally, invasive or disseminated aspergillosis develops in the context of profound and protracted granulocytopenia (Figure 26-1).

Histoplasmosis

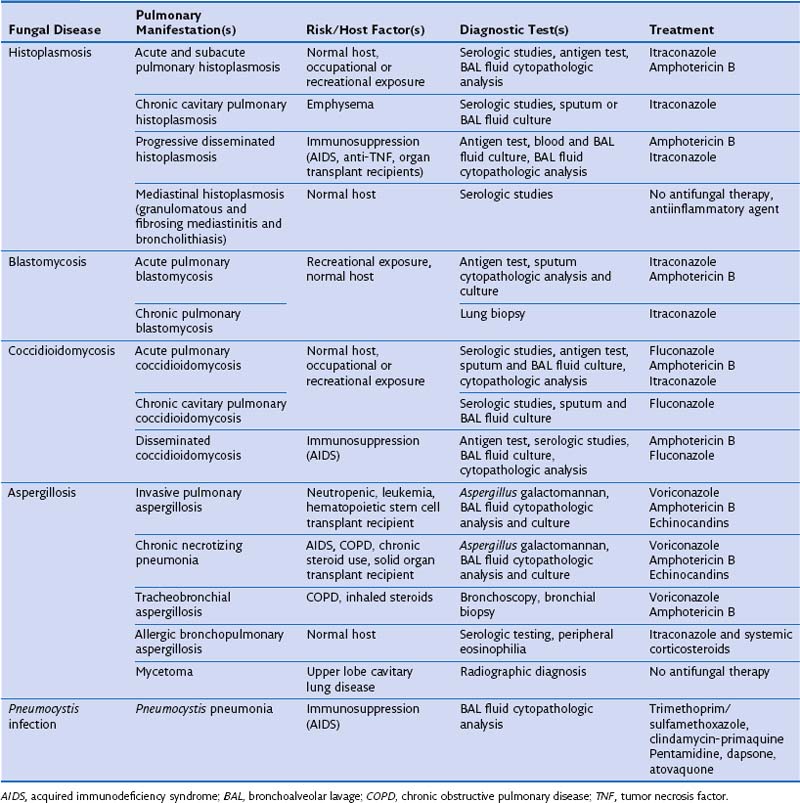

The clinical manifestations of histoplasmosis are variable and depend on the intensity of exposure along with the immune status and underlying lung architecture of the host. The Mississippi and Ohio River valleys are highly endemic. Histoplasmosis also is endemic to parts of Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia. Moist soil is an ideal habitat for Histoplasma, especially when supplemented with bird or bat guano. Activities that can lead to infection include spelunking (caving), excavation, demolition, and cleaning of chicken coops or old buildings. After inhalation, the spores are converted into yeasts, which are phagocytosed by macrophages. The organism is able to survive and proliferate inside macrophages, allowing it to disseminate. Within 2 weeks, however, a protective cellular immune response usually develops, which contains the fungus by forming granulomas (often seen as calcified granulomas on chest radiographs). Most otherwise healthy persons infected with a low inoculum remain asymptomatic (i.e., the infection is subclinical) or are minimally symptomatic. Patients with impaired immunity that fails to contain the infection can develop progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, with involvement of the bone marrow, liver, spleen, adrenal glands, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system (CNS). This manifestation typically is seen in persons with AIDS or patients taking immunosuppressive medications such as prednisone, methotrexate, and anti-TNF-α agents. Common clinical manifestations of disseminated disease include fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, meningitis, focal brain lesions, ulcerations of the oral mucosa, gastrointestinal ulcerations, and adrenal insufficiency. Disseminated histoplasmosis carries a high mortality rate unless promptly diagnosed and appropriately treated (Table 26-1).

Blastomycosis

In view of the cross-reactivity of the antigen assay, it is fortunate that the treatment for severe life-threatening blastomycosis is similar to that for histoplasmosis. Intravenous administration of amphotericin is the treatment of choice, and corticosteroids may be added in cases of ARDS. Non–life-threatening cases can be managed with itraconazole. In patients who are intolerant of itraconazole or who have CNS involvement, fluconazole can be used. Almost all patients with blastomycosis should be treated (Figure 26-2), although patients with self-limited disease may not require treatment.

Parasitic Pneumonias

Carmona EM, Limper AH. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5:41–59.

Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801–1812.

Dutkiewicz R, Hage CA. Aspergillus infections in the critically ill. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:204–209.

Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America: Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1217–1223.

Hage CA, Wheat LJ, Loyd J, et al. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:151–165.

Kuzucu A. Parasitic diseases of the respiratory tract. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:212–221.

Taylor WR, White NJ. Malaria and the lung. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:457–468.

Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America: Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825.