Chapter 3 Non-surgical Facial Rejuventation with Fillers

Summary

Soft Tissue Loss in the Aging Patient

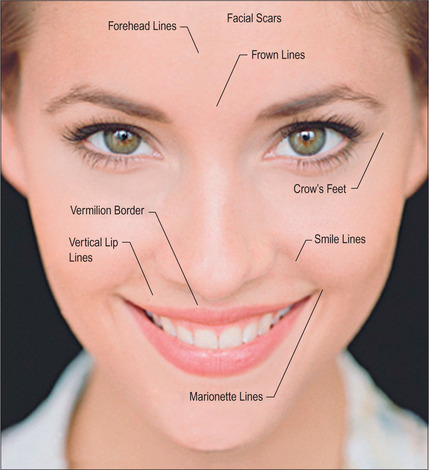

Some of the features that a youthful face exhibits include smooth contours, few wrinkles, except in dynamic expression, and full subcutaneous tissues with minimal or no soft-tissue atrophy (Fig. 3.1). Nasolabial, glabellar and crow’s feet skin folds are almost uniformly absent at rest, and minimally noticeable, even with muscular contraction. During aging of the normal, healthy adult, there is loss of soft-tissue fullness in the face, often beginning in the nasolabial folds and progressing inferiorly along the marionette lines. Lines in the upper face may show years earlier during dynamic expression than at rest. Lipoatrophy can distress the aging patient with resultant low self-image and self-esteem, depression and social isolation.1,2 With the severe rise in obesity in recent years, loss of facial fat due to aging may be partially offset due to fatty accumulation after weight gain.

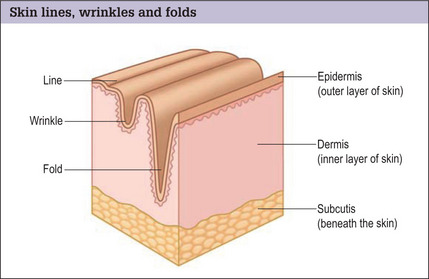

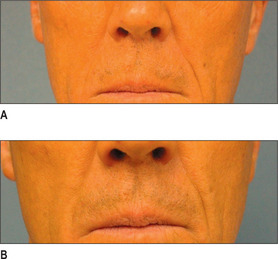

In the normal aging face there is gravitational pull on sagging skin, flattening of the youthful contours, accompanied by solar degeneration, variation in pigmentation, an increase in rhytids, capillary break-down, loss of muscle tonicity and progressive thinning of the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Figs 3.2 and 3.3). One of the hallmarks of aging skin – and one for which we have essentially no topical or minimally invasive corrective solution – is poor elasticity, breakdown of elastic fibers and excess skin envelope. In essence, with an imbalance of soft tissue volume to skin envelope, there are three basic approaches: 1) fill up the lost tissue volume, 2) chemically peel, laser, or mechanical dermabrade or excise the excess skin, or 3) live with the difference. Because few patients have one isolated contributing factor, the ideal approach would often include volume restoration and treating the skin. However, many patients do not desire more aggressive treatment. Chemical peels and lasers chemically denude the superficial layers of the skin, but do not reduce the surface area of the skin sufficiently to balance the loss of soft tissue volume in any but the mildest conditions in the youngest patients. While they tighten the skin, in essence by cross-linking collagen and other proteins, they do not restore the elasticity of youth.

Soft Tissue Loss in Disease Conditions

While less common, certain disease conditions cause premature loss of soft-tissue volume; some are genetic and some acquired. Congenital generalized lipodystrophy (autosomally recessive) results in lack of adipose tissue from birth. Familial partial lipodystrophy (autosomally dominant) causes progressive peripheral fat loss beginning at puberty and, typically, the facial fatty tissue will stay the same, or rarely gain fat, while the body atrophies. Mandibulosacral dysplasia (autosomally recessive) shows two forms: type A demonstrates peripheral fat loss with normal or excess facial fat, while type B shows generalized fat loss. Partial lipodystrophy (autoimmune mediated) presents during childhood or adolescence and the upper body, including the face, presents with fat loss. Excess fat is found in the legs and hips. Generalized lipodystrophy (immune mediated) presents during childhood or adolescence and shows generalized fat loss, including the face.

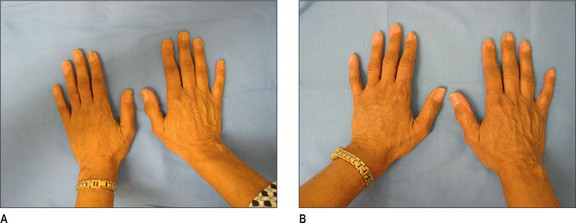

Acquired lipodystrophies arise from multiple mechanisms, but more commonly small localized areas of fat loss may occur from drug injections, local trauma or crush injuries, immune-mediated mechanisms, cancer or HIV, the most prevalent form. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is associated with the condition, but its actual mechanism is unknown. There appears to be some interaction with protease inhibitors and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The HIV patient shows rapid loss of peripheral fat and fat in the face, occurring within 1 year of treatment.3 Fat paradoxically accumulates in the abdomen, breast and dorsocervical spine. In the face, the buccal and temporal fat pads are most locally affected; however, there is loss of fat diffusely in the face. Fat loss may be rapid and progressive and is often permanent, refractory to steroid administration and dietary intervention. The prevalence has been reported as variable (18-83%) due to differing definitions.4 Lipoatrophy in HIV patients can lead to compliance issues, reducing the effect of HAART and accelerating disease progression, fear of stigmatization and recognition.5,6

Indications

Skin lines, wrinkles and folds

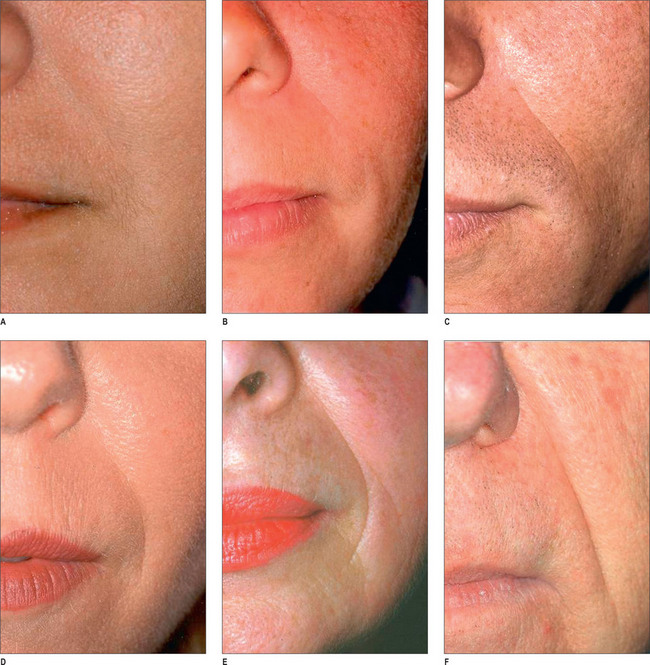

By far the most frequently injected area, the nasolabial fold (NL), may be best evaluated by the standardized Lemperle scale of severity (Fig. 3.4). Natural folds in the face are created by attachment of the facial muscles to the undersurface of the skin. No comparable scale is widely used in the marionette lines, the crow’s feet and/or other skin folds of the face. However, an appropriate approach would be to use the commonly accepted Lemperle scale. The NL fold may begin to appear in the early 20s and progresses with aging. While this scale is primarily focused on skin wrinkling, soft tissue loss is a contributing factor as well.

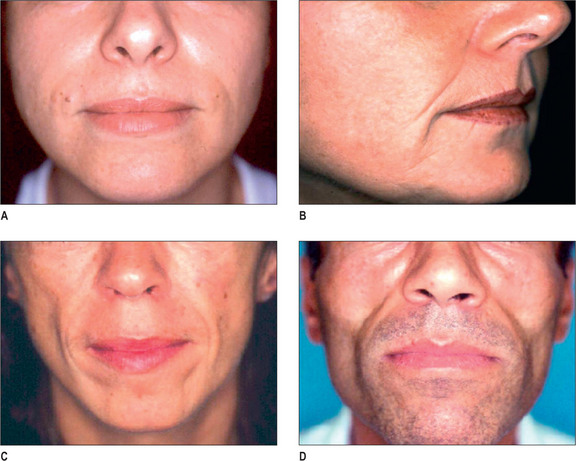

Facial lipoatrophy scale

A four-point grading system is commonly used to measure facial lipoatrophy (Fig. 3.5). Grade 1 is characterized by small localized areas of fat loss, especially in the nasolabial folds. Grade 2 includes mentolabial folds (marionette lines) and may include concavity of the lips. Grade 3 progresses to malar fat atrophy, preauricular hollowing and shadowing of the cheeks and mandibular ridge, while Grade 4 demonstrates malar fat ptosis, temporal hollowing and protruding musculature and bones.

Preoperative History and Considerations

Pre-procedure analysis

Age is an important factor, as approximately 80% of all injections are performed between the ages of 35 and 64.7 Increasing age leads to the tendency of decreased immunogenicity, so, presumably, there would be less of an inflammatory response to a permanent or semi-permanent filler. However, thinner skin and dermal atrophy make superficial injection techniques risky, as lumpiness and color deformity may occur more readily. Avoidance of aspirin, NSAIDs, gingko biloba, St. John’s Wort, and high-dose vitamin E for 1-3 weeks prior to the injection is encouraged.

Injectable Fillers

We have truly entered the ‘filler revolution’ and the number of new fillers on the market is constantly increasing.8 The first injectable filler that was approved by the FDA was bovine collagen (Zyderm/Zyplast; Inamed Aesthetics, Santa Barbara, CA). The need for skin testing and its lack of longevity were key issues hindering its widespread use.9 Since this time, many classes of fillers have been approved by the FDA, with more likely in the future. Listed in this section is a brief description of each of the major injectable fillers currently being utilized in the USA.

Hyaluronic acid

Of the 9.2 million non-surgical cosmetic procedures performed in 2004, almost 900 000 included augmentation using injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers.10 Hyaluronic acid is a glycosaminoglycan that is a naturally occurring polysaccharide. Hyaluronic acid is an essential component of the extracellular matrix, essentially ubiquitous throughout all animal species. Therefore, it has no species or tissue specificity, making HA ideal from an immunologic standpoint. In its native form, catabolism of HA is rapid (hours to days), therefore stabilization via crosslinking is essential for utility as an injectable filler. HA is hydrophilic and able to retain 95% of volume with water.11 Unique to HA is its ability to follow isovolemic degradation, a process by which the remaining molecules of HA are able to bind an increasing amount of water thus maintaining volume until the majority of product is degraded.

Currently, there are several HA derivative products approved by the FDA. All products are approved for mid-to-deep dermal implantation for correction of moderate-to-severe facial wrinkles and folds:12–14 Restylane (Medicis, Scottsdale, AZ), Perlane (Medicis, Scottsdale, AZ), Juvederm (Allergan, Irvine CA), Captique (Allergan, Irvine, CA), and Hyalform (Allergan, Irvine, CA). Restylane was the first of the HA fillers to be FDA approved (12/2003); in initial studies by Narins et al it showed superiority to Zyplast with a smaller concentration of product.15 Restylane has a HA concentration of 20 mg/ml, a gel particle size of 400 μm, and a 1% degree of crosslinking.16 It is distributed in 0.4 ml and 1.0 ml disposable syringes. Wang et al17 recently reported that, in addition to the physiochemical properties of Restylane, it may augment dermal filling by stretching fibroblasts and thereby stimulating de novo collagen formation.

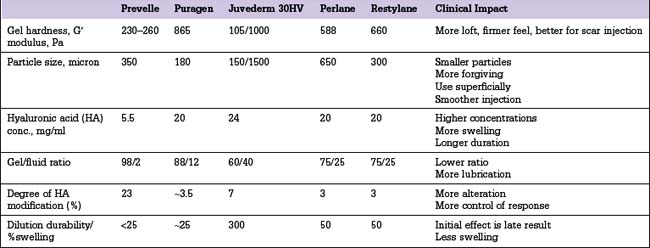

Other HA fillers are similar to Restylane but differ in several key categories: concentration, particle size, and degree of crosslinking. Juvederm was FDA approved in June 2006 and has a slightly higher concentration of HA (24 mg/ml), a higher percentage of crosslinking, and has randomly shaped particles. In addition to Juvederm, two other formulations of Juvederm have been FDA approved. Juvederm Ultra is a thinner version of Juvederm. Juvederm Ultra Plus has a greater particle size and a larger degree of crosslinking, marketed to be utilized as a volumizer injected deeper than its predecessor. Perlane is similar in crosslinking to Restylane; however, like Juvederm Ultra Plus, it has a larger particle size intended to be placed deeper in the dermis and/or subdermis. Restylane, Juvederm, Juvederm Ultra, Juvederm Ultra Plus, and Perlane are all derived from non-animal stabilized HA (NASHA). NASHAs, coupled with the ubiquity of HA, render these injectables as having a low potential for immunogenic reaction. In contrast, Hylaform is derived from rooster combs and does confer immunogenicity. Puragen recently renamed as Prevelle Shape, has been approved in the EU for two years and is double cross-linked with the aim to better resist degradation (Figs 3.6, 3.7 and 3.8).

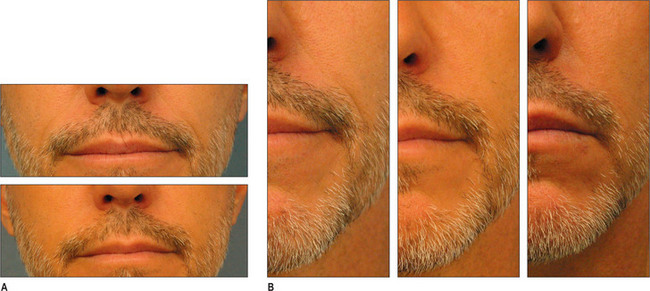

Fig. 3.6 Patient in her 50s 14 months after double cross-linked hyaluronic acid in the nasolabial folds.

Calcium hydroxylapatite

Synthetic calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) is a biocompatible substance with a similar mineral component to bones and teeth. TheCaHA scaffold theoretically allows for tissue ingrowth with no immunogenic or inflammatory response as well as no migration. Radiese(BioForm Medical, San Mateo, CA) is a suspension of 30% CaHAmicrospheres of 25-45 μm in diameter in a gel consisting of 1.3%carboxymethyl cellulose, 6.4% glycerin, and 36.6% sterile water.Radiesse was approved by the FDA in December 2006 for the correctionof soft-tissue wrinkles and folds; however, it was previously approvedfor laryngeal augmentation, soft-tissue marking, and filling/augmenta-tion of dental intraosseous defects and oral/maxillofacial defects.18 It is also now approved for correction of HIV facial lipoatrophy.19

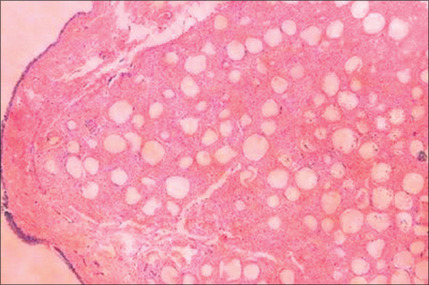

Histologically, by 3 months, there is some residual phagocytosis ofthe gel substrate and a fine fibrous stroma between the CaHA microspheres (Fig. 3.9). By 9 months, there is irregularity of the shape ofthe CaHA microspheres, presumably from enzymatic degradation. Noforeign body granulomatous reactions have been identified (Fig. 3.10).20–23 Radiesse has been reported to persist histologically from 2 to 7 years.24

Poly-L-lactic acid

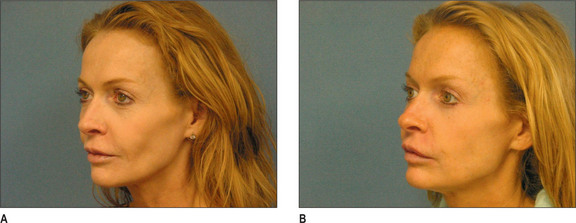

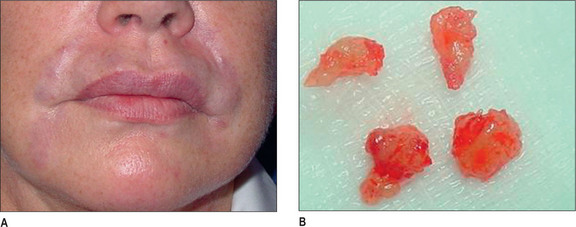

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLA) is a synthetically polymerized lactic acid material first synthesized from vegetable sources in 1954 and used in multiple surgical devices, including suture materials (DEXON (Davis & Geck, Manati, Puerto Rico), VICRYL (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, N.J.), and in resorbable plates and screws, as well as a vehicle for sustained drug release. Sculptra (New-Fill in Europe) is manufactured in Italy and distributed in the USA by Dermik Laboratories (Berwyn, PA – Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ). Sculptra is formulated into PLA microspheres (40-63 μm) suspended in a sodium carboxymethylcellulose carrier and reconstituted with sterile water. Sculptra was FDA approved in 2004 for correction of facial lipoatrophy in HIV patients (Figs 3.11 and 3.12).

Following solubilization, the lactic acid degrades via the lactate/ pyruvate route, and is then eliminated as CO2 through the respiratory system.25 Histologically, no polymer is detected after 9 months.21 Tissue filling is ultimately achieved by ingrowth of type I collagen (neocollagenosis).26 Thus, the filling persists despite resorption of polylactic acid microparticles. Investigations in HIV lipoatrophy have revealed increased dermal thickness by threefold, as well as increasing the quality of life in this group of patients.27,28

Polymethylmethracylate beads coated in collagen

Polymethylmethracylate (PMMA) microspheres are insoluble, synthetic and chemically related to Plexiglas. PMMA is commonly used in orthopedics for permanent fixation and support of bony tissues. ArteFill (San Diego, CA) is composed of a 20% solution of PMMA microspheres 30-42 μm in diameter and suspended in a solution of partly denatured bovine collagen and 0.3% lidocaine. ArteFill received FDA approval in January 2007 for correction of facial wrinkles, thus making it the first permanent injectable wrinkle filler in the USA.29 Patients must be skin tested for allergy to bovine collagen and possibly tested for reactivity to collagen.30

Artecoll, the identical product with previous marketing nomenclature, has been implemented throughout the world since 1994. Reportedly 400 000 patients have been treated to date.31,32 The PMMA microspheres are non-biodegradeable and are unable to be phagocytosed by macrophages, due to their size and lack of electrical charge. Thus, soft-tissue augmentation is thought to be permanent. By 1 month post-injection, each individual microsphere is encapsulated by collagen, macrophages, and fibroblasts. Resorption of the bovine collagen and replacement with native collagen occurs within 1-3 months. The size of the Artecoll microspheres is unchanged by 9 months.21,33

Injected in small amounts and corrected less than 1 : 1 in volume, excellent results can be extremely pleasing clinically, as good as or better than any others. The injectate is permanent and may not show at all, or potentially after the normal soft-tissue atrophy of aging occurs years later. Experience has not ranged over sufficient years since introduction about 10 years ago to be sure of the clinical significance of this possibility.34 If there is a complication, the results may respond to triamcinolone injection, or may require excision, because the body cannot resorb this synthetic polymer.

Polyacrylamide gel

Aquamid (manufactured by Ferrosan, Copenhagen, Denmark; distributed by Contura International, Soeberg, Denmark) consists of 2.5% crosslinked polyacrylamide and 97.5% water. Polyacrylamide injected into the subcutaneous tissues elicits a fibrous capsule that surrounds the gel by 6-9 months.21 This material is currently not approved by the FDA; however, it is in use throughout Europe, South America, and the Middle East.

Operative Approach

Anesthesia

While many patients are able to tolerate neurotoxin injections without the use of anesthesia, most patients require an anesthetic to ensure maximal comfort for the injection of fillers such as the HAs. Especially in extremely sensitive areas such as the lips, an otherwise good experience can leave lasting memories of anxiety and pain, which may curb a patient’s desire to have repetitive treatments. Areas such as the region under the eyes may require a much lower level of anesthesia, and, as such, choice of an anesthetic must be tailored to the patient, the material being injected, and the area of treatment.

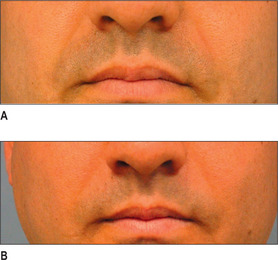

Nasolabial folds

To achieve optimal results and longevity, the nasolabial folds must be maximally corrected. Less than maximal correction often contributes to patient dissatisfaction. Studies examining longevity treated patients to maximal correction and, as such, patients not receiving maximal correction cannot be expected to have as long-lasting a result. Indeed, complete correction and placement of the materials in the proper plane appear to be key factors for success.17

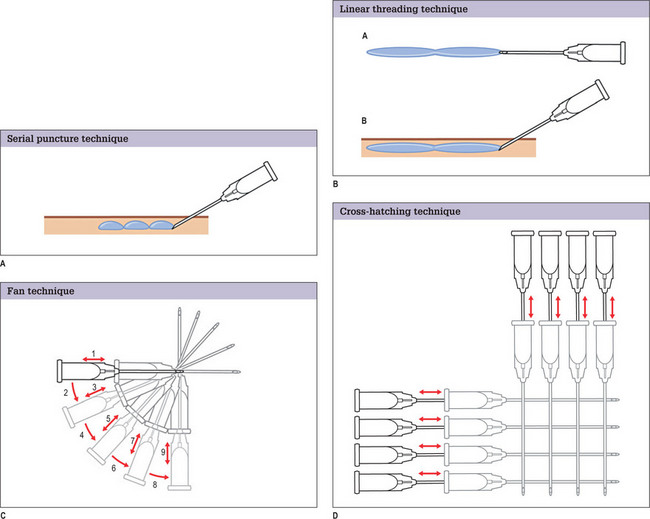

Glabellar lines

In general, glabellar rhytids are best and most frequently treated with botulinum toxin. However, for patients with particularly deep lines, the neurotoxin may not provide sufficient improvement to appropriately eliminate these creases. In such patients, a synergistic effect can be obtained by using a filler in combination with the neurotoxin.33 Others have reported that concurrent injection of Restylane® and botulinum toxin increases the longevity of the former.35 The serial puncture technique is used, staying in the mid-dermis. Injection occurs as the needle is being withdrawn. It may be useful to compress the supratrochlear vessels to minimize likelihood of intravascular injection.

Bruising is not uncommon in this region. Multiple cases of skin necrosis and scarring have been reported in the literature, particularly in this region.36,37 Immediate care of prolonged skin blanch after injection involves massage to stimulate blood flow into the region. If this is not effective topical 2% nitroglycerine ointment can be applied.

Lower eyelids (nasojugal groove and tear trough regions)

One of the more difficult areas to treat successfully is that area of the lower eyelids. However, a good result is equated with high degrees of patient satisfaction.38 Significant hollowing occurs as a result of pseudoherniation of orbital fat combined with descent of the buccal fat. This may also result as a result of cosmetic lower blepharoplasty. The thin, delicate nature of the skin makes this area a challenge. The area bruises very easily, especially in patients with clotting abnormalities, those prone to bleeding, or in whom pharmaceuticals are used that interfere with normal clotting. Fillers injected just beneath the surface of the very thin skin can be visible, and are to be avoided. For this reason, many clinicians are reluctant to inject the tear trough region. Surgeons who have an excellent understanding of the orbital and lid anatomy form having operated upon it in the past are well-prepared to inject in an entirely different plane than discussed with the other subsited thus far. The filler should be injected beneath the orbicularis muscle, overlying the periosteum, serially along the orbital rim. Surface irregularities can in this way be minimized. Undercor-rection is preferred to overcorrection. As the HAs are hydrophilic and attract water in the first few weeks after the filler is placed, complete correction can actually become overcorrection, and the eyes may take on a puffy appearance. More than any other area, bruising can occur and so patients need to account for this to ensure that whatever bruising does occur does not interfere with their lifestyle.

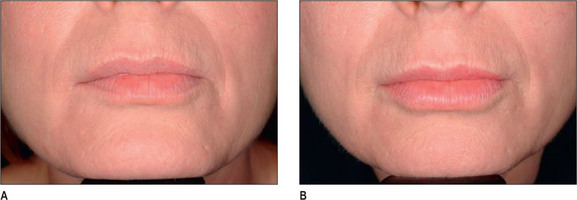

Lips

Generally, HA, having supplanted the use of collagen in the last 3-4 years, is the injectate of choice in the lip (Fig. 3.14). CaHA, PMMA and PLA are generally not indicated in the lips and should be used with great caution except in the hands of the experienced injector and the experienced patient who know the doctor well.

Other important details

Complications and Side Effects

The first five on the list are relative common adverse events, are almost always transitory and responsive to palliative treatment. Asymmetry is almost always present, but those cases leading to dissatisfaction are relative uncommon. Hematoma, while relatively more uncommon, is also short-lived and generally easy to treat. Allergy implies exposure to protein, and in HA preparations it is residual from the production process of bacterial fermentation. Protein loads in HA preparations is in the order of 1 part per million. This is generally not a problem with CaHA and PLA, but PMMA has an outer coating of collagen and carries the risk of allergy, just as traditional collagen injection does. However, hypersensitivity reactions may occur many months after treatment. In a study of 709 patients injected with Hylaform or Resylane followed-up for 12 months or more, six developed delayed skin reactions 8 weeks after injections.39 In a 1999 study, localized hypersensitivity reactions occurred in approximately 1 in 1400 patients, and adverse events were reported in one in 650 patients (0.15%). In 2000, when the amount of protein in the raw product decreased, those numbers fell to one in 5000 for hypersensitivity reactions and one in 1800 for adverse events (0.06%). Andre performed a retrospective study evaluating the incidence of adverse reactions after non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid injections and found an overall 0.8% global risk of hypersensitivity reactions, of which 50% were immediate and resolved in under 3 weeks.40

Postoperative Care

Immediate post-injection treatment is minimal, but varies with each material. Generally, the patient is kept in the office for 5-10 minutes with cold compresses applied to monitor for hematoma, nodularity, palpability or other problems. No dressings are required and makeup may be applied before leaving the office. Much discussion has occurred about having patients refrain from vigorous physical activity for several days, but this has no scientifically validated foundation. It is left to the preference of the individual doctor and patient.

1. Kligman A.M. Psychological aspects of skin disorders in the elderly. Cutis. 1989;43(5):498-501.

2. Grossbart T.A., Sarwar D.B. Cosmetic surgery: surgical tools – psychosocial goals. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1999;18(2):101-111.

3. Miller J., Carr A., Smith D., et al. Lipodystrophy following antiretroviral therapy of primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2000;14:2406-2407.

4. Carr A. HIV lipodystrophy: risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. AIDS. 2003;17(suppl1):S141-S148.

5. Ammassari A., et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):140-144.

6. Collins E., Wagner C., Walmsley S. Psychosocial impact of the lipodystrophy syndrome in HIV infection. AIDS Read. 2000;10(9):546-550.

7. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics 2004, A.S.f.A.P. Surgery, Editor. 2005.

8. Dover J. The filler revolution has just begun. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:38S-39S.

9. Kinney B. Soft tissue fillers: An overview. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2001;21:469. HC III

10. Rohrich R.R. Introduction to the restylane consensus statement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(3):1s-2s.

11. Matarasso S.L., Carruthers J.D., Jewell M.L. Restylane Consensus Group. Consensus recommendations for soft tissue augmentation with nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:3S-34S.

12. Captique injectable gel (Package Insert), Inamed Aesthetics: Santa Barbara, CA.

13. Hyalform (hylan B gel) (Package Insert), Inamed Aesthetics: Santa Barbara, CA.

14. Hyalaform Plus (hylan B gel) (Package Insert), Inamed Aesthetics: Santa Barbara, CA.

15. Narins R., Brandt F., Leyden J., Lorenc Z.P., Rubin M., Smith S. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:588-595.

16. Olenius M. The first clinical study using a new biodegradable implant for the treatment of lips, wrinkles, and folds. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998;22:97-101.

17. Wang F., Garza L.A., Kang S., Varani J., Orringer J.S., Fisher G.J., Voorhees J.J. In vivo stimulation of de novo collagen production caused by cross- linked hyaluronic acid dermal filler injections in photodamaged human skin. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:155-163.

18. Jacovella P., Peiretti C.B., Cunille D., Salzamendi M., Schechtel S.A. Long lasting results with hydroxylapatite facial filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3):15S-21S.

19. Silvers S., Eviatar J.A., Echavez M.I., Pappas A.L. Prospective open label 18-month trial of calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) for facial soft tissue augmentation in patients with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: One year durability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3):34S-45S.

20. Sklar J., White S. Radiance FN, a new soft tissue filler. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(5):764-768.

21. Lemperle G., Morhenn V., Charrier U. Human histology and persistence of various injectable filler substances for soft tissue augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27:354.

22. Mayer R., Lightfoot, Jung T. Preliminary evaluation of calcium hydroxylapatite as a transurethral bulking agent for stress urinary incontinence. Urology. 2001;57:434.

23. Probeck H., Rothstein S. Histologic observation of soft tissue responses to imported multifaceted particles and discs of hydroxylapatite. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;42:143.

24. Marmur E., Phelps R., Goldberg D. Clinical, histologic and electron microscopic findings after injection of calcium hydroxylapatite filler. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2004;6:223.

25. Brady J., Cutright D., Miller R., et al. Resorption rate route, route of elimination, and ultra structure of the implant site of polylactic acid in the abdominal wall of the rat. J Biomed Water Res. 1973;7(2):155-156.

26. Vleggaar D., Bauer U. Facial enhancement and the European experience with Sculptra (poly-l-lactic acid). J Drugs Dermatology. 2004;3:542.

27. Valantin M., Aubron-Olivier C., Ghosn J., et al. Polylactic acid implants (New-Fill) to correct facial lipoatrophy in HIV-infected patients: Results of the open label study VEGA. AIDS. 2003;17:2471.

28. Moyle G., Lysakova L., Brown S., Sibtain N., Healy J., Priest C., Mandalia S., Barton S.E. A randomized open label study of immediate versus delayed polylactic acid injections for the cosmetic management of facial lipoatrophy in persons with HIV infection. HIV Medicine. 2004;5:82.

29. Cohen S., Berner C.F., Busso M., et al. ArteFill: A long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material – summary of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration trials and a progress report on 4 to 5 year outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3):64S-76S.

30. Elson M. The role of skin testing in the use of collagen injectable materials. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:301.

31. Lemperle G., Romano J., Busso M. Soft tissue augmentation with artecoll: 10 year history, indications, technique, and potential side effects. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:627.

32. Cohen S., Holmes R. Artecoll: A long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material. Report of a controlled, randomized, multicenter clinical trial of 251 subjects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:964.

33. Narins R., Bowman P. Injectable skin fillers. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:151.

34. Lemperle G., Fazio S., Nicolau P. Artefill: A third generation permanent dermal filler and tissue stimulator. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:551-565.

35. Carruthers J., Carruthers A. A prospective, randomized, parallel group study analyzing the effect of BTX-A (Botox) and nonanimal sourced hyaluronic acid (NASHA, Restylane) in combination compared with NASHA (Restylane) alone in severe glabellar rhytides in adult female subjects: treatment of severe glabellar rhytides with a hyaluronic acid derivative compared with a hyaluronic acid derivative compared with the derivative and BTX-A. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:802-809.

36. Glaich A.S., Cohen J.L., Goldberg L.H. Injection necrosis of the glabella: protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(2):276-281.

37. Duffy D.M. Complications of fillers: overview. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(4):1626S-1633S.

38. Hirsch R.J., Carruthers J., Carruthers A. Infraorbital hollow treatment by dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(9):1116-1119.

39. Lowe N.J., Maxwell C.A., Lowe P., Duick M.G., Shah K. Hyaluronic acid skin fillers: Adverse reactions and skin testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:930.

40. Andre P. Evaluation of the safety of a non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid in European countries: A retrospective study from 1997 to 2001. J EurAcad Dermatol. 2004;18:422.