5 Non-organic neurological diseases

History

Having made the distinction, history is the tool that differentiates tension-type headache from migraine. Tension-type headache may well be a ‘front’ for non-organic disease. Particularly in societies in which physical fitness is a primary requirement, as is the case for members of the armed forces, patients often find it unacceptable to present with complaints of a psychological nature. Once tension-type headache becomes apparent, then the general practitioner is in an ideal position to seek and deal with the cause of the tension. The same applies to various complaints of pain. An example of this is the chest pain that accompanies da Costa’s syndrome, which is a left inframammary pain attached to stressful situations. It is unlike the pain that reflects ischaemic heart disease or chest infection. This should raise the red flag of probable psychological illness but this warning does not negate the need to investigate for both cardiac and pulmonary disease. An early suggestion that the primary diagnosis is most likely non-organic, allows a strengthening of the doctor–patient relationship and potential for mutual respect while the auxiliary investigations proceed.

Examination

A claim of monocular diplopia, in the absence of nystagmus, lenticular dislocation as occurs in Marfan’s syndrome or other obvious pathology, indicates that the final diagnosis is most likely non-organic. Nevertheless, the patient requires proper cranial nerve testing. The claim of monocular diplopia should be a red flag for non-organic disease. Further investigation is dependent upon what other features have emerged, either during the history taking or other examination. Recently, a patient complaining of monocular diplopia was shown on MRI to have her lens dislocated to the back of the globe. This confirmed the potential, thereby dispelling the diagnosis of functional illness. Suspicion of non-organic disease does not suggest the general practitioner should not fully investigate for organic diseases. It allows the doctor to reassure the patient that the investigations are expected to be negative and thus reduce fear of probable devastating findings. This in turn serves to reduce the risk of ‘sick’ role-play by the patient.

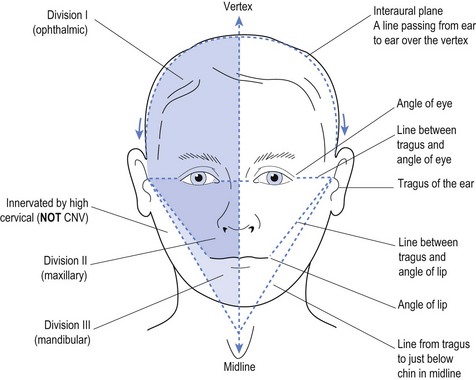

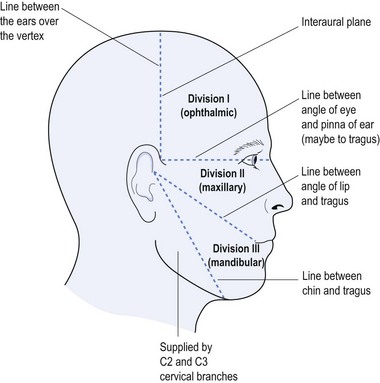

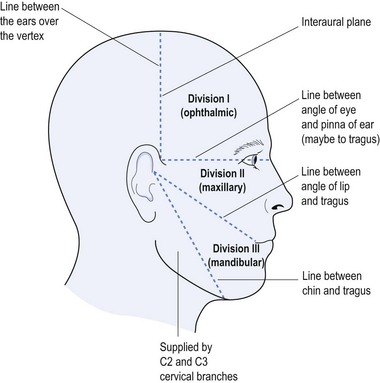

The trigeminal nerve provides a most fertile ground for the definition of functional illness. As demonstrated in Chapter 3, the trigeminal nerve has defined anatomical demarcation of its boundaries of sensory representation (see Figs 5.1 and 5.2).

As the interaural plane defines the limit of the ophthalmic branch of the CN V, it follows that sensory change occurring at other than this plane is anatomically unsound. Many patients with non-organic disease will identify sensory change at the start of the hairline on the forehead. This provides unequivocal evidence of functional illness. The same applies when the patient claims the angle of the jaw as the site of sensory change. The angle of the jaw, below the line from the tragus of the ear to the midline (just below the jaw), is innervated by high cervical roots (especially C2 and C3) (see Figs 5.1 and 5.2). A patient identifying sensory change at the angle of the jaw offers unequivocal evidence of functional illness.

Every clinical practice should have the dermatomal map available for scrutiny. An invaluable reference is Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system (O’Brien 2010), which is a MUST for all serious clinicians interested in the nervous system. There are some useful landmarks to remember that will allow the examiner to localise lesions with ease (see Box 5.1). A more complete dermatomal map has not been provided here as the above reference is both cheap and invaluable.

Box 5.1 Anatomical landmarks re sensation

| Anatomy (anterior) | Dermatome |

|---|---|

| Root of neck and shoulders | C3, C4 |

| Level of nipple | T4 |

| Level of costochondral margin | T6 |

| Umbilicus | T10 |

| Pelvis | T12 |

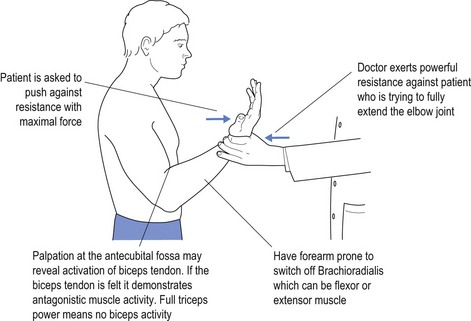

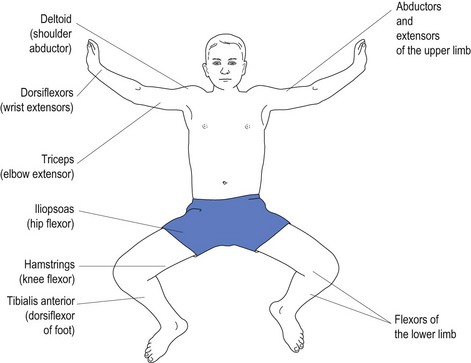

The cranial nerves are not the only source of definition of non-organicity. Patients who complain of weakness of muscles, when asked to exert maximal effort from a specific muscle or muscle group, may show activation of antagonistic muscle groups. An example of this might be the patient claiming weakness of the triceps muscle, but when strength in this muscle is tested there is clear evidence of biceps involvement (see Fig 5.3).

Activation of antagonistic muscle(s), within the context of testing ‘maximal’ power of a specific muscle or muscle group, offers unequivocal evidence of suboptimal effort. This does not mean the patient is aware of so acting on a conscious level, but does offer clear evidence of functional illness.

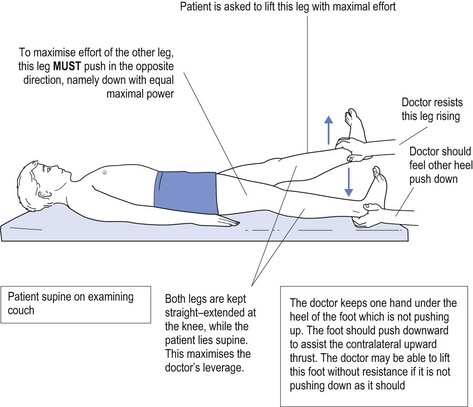

Another region in which weakness may reveal functional illness is in the examination of lower limb power in a patient who is lying down (see Fig 5.4).

Hoover’s sign relies on Newton’s third law—namely, ‘for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction’. The patient is asked to lift up one leg with maximal power against resistance while lying flat. The doctor resists the effort to lift this leg while placing their other hand under the heel of the other foot. Based on Newton’s third law this foot must push down to maximise the upward effort of the opposite leg. In the patient who is not pushing up with maximal effort, the doctor will not feel the downward thrust of the heel, a positive Hoover’s sign. The doctor may even be able to lift the heel effortlessly because of the lack of downward force. This further emphasises non-organicity. A positive Hoover’s sign provides unequivocal support for the diagnosis of functional illness. Such finding opens the way to explore the underlying cause for such behaviour.

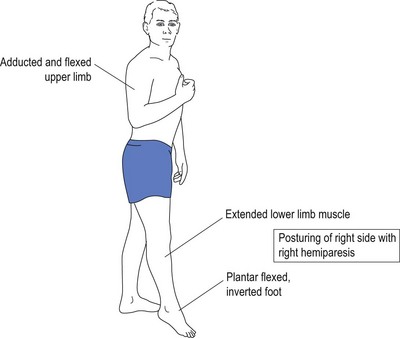

As demonstrated in Chapter 4, neurological diseases assume a set pattern of presentation. This is particularly so for upper motor neurone deficit which affects antigravity muscles (Fig 5.5). Damage, as evidenced by hemiparesis, causes a set pattern of weakness, with resultant unequal power in the muscles that oppose the antigravity muscles (Fig 5.6).

Conclusion

As stated earlier, a detailed neurological history and examination arms the doctor with an appreciation of what to expect. When the findings fail to live up to expectation, then the doctor should consider ‘functional illness’ among the differential diagnoses. Just because ‘functional illness’ appears on the list of potential diagnoses, it does not stop the doctor fully investigating other possibilities.