Non-mechanical disorders of the lumbar spine

Warning signs

Introduction

The majority of lumbar spine syndromes encountered in clinical practice result from mechanical – activity-related – disorders. They can be classified into dural, ligamentous and stenotic syndromes. Lumbar syndromes, however, can also stem from non-mechanical – non-activity-related – disorders affecting the spine. These are: inflammatory diseases, both septic and rheumatological; tumours and infiltrative lesions; metabolic disorders; and acquired defects in the neural arch. Finally, pain in the lower back, groin and pelvic area can be referred from visceral organs (see online chapter Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen). Pain in buttocks, groin and limb, as the result of reference from the sacroiliac and hip joints, although ‘activity-related’, does not have a spinal origin and is discussed thoroughly in the chapters on the hip joint and sacroiliac joint.

Although the occurrence of non-mechanical (non-activity-related) disorders is rare, it is important to differentiate them as quickly as possible from mechanical activity-related lesions. This is never easy, because these disorders frequently mimic other, more specific lumbar lesions. Sometimes the diagnosis is made radiologically but very often this is of no help, especially in the early stages of an inflammatory or neoplastic disease. A thorough history and clinical examination are what will first draw attention to the possibility of a non-activity-related disorder: the history may show an unusual localization or an atypical evolution of the pain; particular clinical signs may arouse suspicion. Most of all, however, it is the comparison between history and clinical examination, resulting in the existence of ‘unlikelihoods’, that focuses attention on serious spinal pathology such as vertebral fracture, malignancy, infection or inflammatory disease.1

Warning signs in backache and sciatica

Symptoms and signs that almost invariably point to non-mechanical disorders are termed ‘warning signs’ here. The finding of such signs indicates that the existence of a non-specific disorder in the lumbar spine is very likely. A patient presenting with a warning sign should never be considered to be suffering from a common mechanical disorder until the contrary has been proved. It is important, therefore, always to have confirmatory investigations carried out (radiography, bone scan, computed tomography (CT) and blood tests) to settle the diagnosis. It is also the duty of a physiotherapist who is asked to give active treatment (manipulation or traction) to a patient presenting with warning signs to report this to the referring doctor, and to send the patient back with a request for further thorough examination.2

Symptoms

Significant trauma

It is obvious that the statement of a significant trauma prior to the development of backache should be reason to ask for further imaging studies, especially if the patient is aged over 70 years and uses corticosteroids.3,4

Deteriorating general health

Unexplained weight loss, fever, feeling systematically unwell (tired, loss of appetite) and a previous history of cancer are all considered as potential symptoms of a serious illness.5

Pain in the ‘forbidden area’

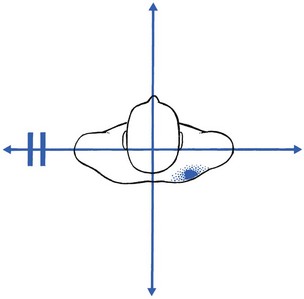

In the upper lumbar region pain is very seldom the result of a mechanical lesion. Disc lesions almost never occur at the first and second levels,6 and even third lumbar lesions constitute only 5% of lumbar disorders.7 Also, ligamentous lesions and recess stenosis do not seem to occur at these upper lumbar levels. Hence, if a patient has pain at the upper lumbar level – the ‘forbidden area’ (Fig. 39.1) – the suspicion is aroused that a non-mechanical lesion is present. Ankylosing spondylitis, neoplasm, tuberculosis, aortic thrombosis or reference from a viscus may then be possibilities (Cyriax8: p. 26).

Fig 39.1 The ‘forbidden area’.

Bilateral sciatica

• Spondylolisthesis can cause bilateral radicular pain, which presumably results from the forward movement of the listhetic vertebra, pulling the nerve roots painfully against the shelf formed by the stable vertebra below.

• A disc lesion resulting in bilateral sciatica is rare and should always be taken seriously because it probably means a massive protrusion, which poses a risk to the S4 root.9 Bladder incontinence and numbness in the saddle area may then accompany the bilateral root pain. Rarely, a disc develops two protrusions, one at each side of the posterior longitudinal ligament; alternatively, two protrusions, one at the fourth level and one at the fifth, are present.

• Bilateral lateral recess stenosis or a narrowed spinal canal can also be the cause of bilateral sciatica. In the former, the typical history of increasing pain in the upright position is informative. In the latter, the patient mentions neurogenic claudication.

• Malignant disease is indicated by rapidly increasing bilateral sciatica, often spreading into the limbs in a distribution which corresponds to too many dermatomes.

Signs

Discrepancy between articular and dural signs

• In a pathological fracture of a vertebra, resulting from a malignant disease or from senile osteoporosis, there is gross limitation of spinal movements but straight leg raising may remain normal and painless.

• In ankylosing spondylitis, an acute sprain of the stiffened lumbar joints will result in acute lumbago but dural signs are completely absent.

• In chronic afebrile osteomyelitis of a lumbar vertebral body, there is a gross contrast between the marked articular signs and the complete absence of dural signs.

Gross limitation of side flexion away from the painful side

Gross limitation of side flexion away from the painful side (Fig. 39.2) is a common finding in acute disc lesions, in which it always appears in combination with other limited and painful movements, together forming the non-capsular pattern. However, when limitation of side flexion away from the painful side is the only positive lumbar feature, a disc lesion is never present and a serious extra-articular lesion must be suspected. This pattern suggests an abdominal neoplasm, usually carcinoma of colon or kidney, although a neuroma at the lumbar or lower thoracic level should also be considered.

Deficit of L1 and L2 roots

Disc lesions at the first and second lumbar levels are extremely rare; the estimated frequency is between 0.3 and 0.5%.12–14 Also, lateral recess stenosis leading to muscular weakness does not occur at the upper lumbar levels. Therefore, if weakness of the psoas muscle is encountered, the initial diagnosis should never be a disc lesion but rather a serious non-mechanical disorder. In a neoplasm at the second lumbar level, a bilateral paresis is likely to appear. If unilateral weakness is accompanied by pain in the iliac fossa, brought on when the muscle contracts, a neoplasm at the iliac crest or in the pelvis is possible. If the weakness is accompanied by pain in the thigh, metastatic invasion of the upper femur is probable (see Ch. 48).

Presence of the ‘sign of the buttock’

When the sign of the buttock is encountered, a serious lesion in the lumbopelvic area is always present (see Ch. 47). This can be a malignant deposit in the sacrum, iliac bone or femur, septic arthritis of the sacroiliac joint or a rectal abscess.

A warm foot on the affected side

In radicular pain caused by disc lesions, patients often complain that the foot and the leg on the affected side feel cold, which is often confirmed by palpation. If, by contrast, the affected side is warmer, neoplasm at the upper lumbar level should be suspected (Cyriax8: p. 292). The explanation is probably interference by the tumour with the sympathetic nerves at L1 and L2.

References

1. Deyo, RA, Rainville, J, Kent, DL, What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA 1992; 268:760–765. ![]()

2. Ferguson, F, Holdsworth, L, Rafferty, D, Low back pain and physiotherapy use of red flags: the evidence from Scotland. Physiotherapy. 2010;96(4):282–288. ![]()

3. Henschke, N, Maher, CG, Refshauge, KM, et al, Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(10):3072–3080. ![]()

4. Old, JL, Calvert, M, Vertebral compression fractures in the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(1):111–116. ![]()

5. Portenoy, RK, Lipton, RB, Foley, KM, Back pain in the cancer patient: an algorithm for evaluation and management. Neurology 1987; 37:134–138. ![]()

6. De Palma, A, Rothman, RH. The Intervertebral Disc. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1970.

7. Albert, TJ, Balderston, RA, Heller, JG, et al, Upper lumbar disc herniations. J Spinal Disord 1993; 6:351–359. ![]()

8. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

9. Shi, J, Jia, L, Yuan, W, et al, Clinical classification of cauda equina syndrome for proper treatment. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):391–395. ![]()

10. Silber, JS, Anderson, DG, Vaccaro, AR, et al, Management of postprocedural discitis. Spine J. 2002;2(4):279–287. ![]()

11. Sobottke, R, Röllinghoff, M, Zarghooni, K, et al, Spondylodiscitis in the elderly patient: clinical mid-term results and quality of life. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(9):1083–1091. ![]()

12. Gurdjian, ES, Thomas, LM. Neckache and Backache. Springfield: Thomas; 1970.

13. Armstrong, J. Lumbar Disc Lesions. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1965.

14. Krämer, J. Intervertebral Disk Diseases. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1981.