Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Classification

The current WHO classification avoids the overly simplistic high-grade/low-grade split and divides lymphomas into more specific subtypes based on clinical features, morphology, immunophenotype, karyotype and molecular characteristics. In addition to NHL and Hodgkin’s lymphoma the WHO scheme contains a number of other lymphoid neoplasms occurring mainly at extranodal sites that are discussed elsewhere (e.g. myeloma, hairy cell leukaemia). Some of the major entities are shown in Table 30.1.

Table 30.1

The WHO classification of lymphoid malignancy1

With respect to NHL, approximately 90% of cases are of B-cell type and 10% of T-cell type. The commonest NHL entities are follicular (20–25% of all cases) and diffuse large B-cell (30–35%)

B-cell proliferations of uncertain malignant potential

T-cell and putative NK-cell neoplasms

Clinical presentation

Nodal involvement. Painless lymphadenopathy (Fig 30.1), often in the cervical region, is the most common presentation of NHL. Enlarged nodes may cause complications such as superior vena cava syndrome and hydronephrosis.

Nodal involvement. Painless lymphadenopathy (Fig 30.1), often in the cervical region, is the most common presentation of NHL. Enlarged nodes may cause complications such as superior vena cava syndrome and hydronephrosis.

Extranodal involvement. Intestinal lymphoma can present with vague abdominal pain, anaemia (caused by bleeding) or dysphagia. CNS disease frequently leads to headache and cranial nerve palsies and may cause spinal cord compression. Lymphoma may arise in the skin (e.g. mycosis fungoides). Bone marrow involvement is more common in low-grade lymphomas and can result in pancytopenia.

Extranodal involvement. Intestinal lymphoma can present with vague abdominal pain, anaemia (caused by bleeding) or dysphagia. CNS disease frequently leads to headache and cranial nerve palsies and may cause spinal cord compression. Lymphoma may arise in the skin (e.g. mycosis fungoides). Bone marrow involvement is more common in low-grade lymphomas and can result in pancytopenia.

Systemic symptoms. Sweating and significant weight loss occur in less than a quarter of patients and, where present, usually indicate advanced disease. Occasionally, patients present with metabolic complications such as hyperuricaemia, renal failure and hypercalcaemia.

Systemic symptoms. Sweating and significant weight loss occur in less than a quarter of patients and, where present, usually indicate advanced disease. Occasionally, patients present with metabolic complications such as hyperuricaemia, renal failure and hypercalcaemia.

Diagnosis and staging

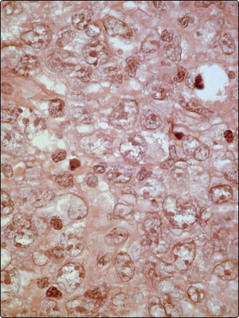

Diagnosis depends on obtaining a tissue biopsy, usually a lymph node, for histological examination (Fig 30.2). Immunophenotyping is used to identify the degree of maturation of the malignant cell and determine whether it is of B- or T-cell origin. B-cell antigenic ‘markers’ include CD19, 20 and 22 and T-cell markers CD2, 3, 5 and 7. Gene rearrangement studies also aid identification. B-cell lymphomas have their immunoglobulin genes clonally rearranged while in T-cell lymphomas there is clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor genes. Molecular techniques (see p. 100) are being increasingly used to detect chromosome abnormalities and to derive prognostic information.

Fig 30.2 Section of a cervical lymph node showing extensive infiltration with large poorly differentiated lymphoid cells typical of diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The staging system is similar to that used in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Patients are staged with CT scanning (Fig 30.3), MRI or PET, and a bone marrow aspirate and trephine. However, in NHL the stage plays a more modest role in management than in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The histological type of the tumour is more closely related to the likely clinical course and other factors impinge upon prognosis. An international prognostic index (IPI), based on age, stage, bulk of disease, performance status and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, is commonly used (see Appendix III).