Chapter 75 Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Etiology and Epidemiology

The incidence of NHL has been increasing worldwide,1 including in North America.2,3 In 2011, the American Cancer Society estimated that 66,360 new cases were diagnosed and 19,320 deaths occurred in the United States.4 In many developed countries there was evidence for a 2% to 4% per year rise in the incidence of NHL from the 1970s to 1990s, and this stabilized in the past decade. This increase is more marked for older persons. In the United States the annual rise in incidence rate had slowed to 1% to 2% in the 1990s.2,3 Some of the increase has been due to increase in immunosuppression (HIV infection and iatrogenic), spread of infectious agents such as human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), increased use of chemicals, and increased case finding due to improved pathologic diagnosis. However, these factors do not explain the magnitude of the rise in incidence.

The epidemiology of certain histologic subtypes of lymphomas follows distinct patterns related to the epidemiology of the putative causative agent and any environmental cofactors. The classic example is Burkitt’s lymphoma in Africa, with the endemic role of EBV and the contribution of immunosuppression because of malaria infection.5 Similarly, EBV-related T-cell/natural killer (NK) cell lymphoma of the nasal region is more frequent in the Asian population in south Asia.6,7 Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma caused by HTLV-1 is endemic in the Caribbean and southern Japan.8 The frequency of HIV-related lymphomas is proportional to the HIV infection rate in the population, explaining the observation of high incidence rates in large urban cities and a role of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus.9 MALT lymphomas of the stomach are seen more frequently in regions where Helicobacter pylori infection is endemic.

Despite an increasing body of knowledge on the genetic and phenotypic events underlying the development and progression of NHL, the causative agent has not been identified in the majority of cases. The putative causative agents and associated conditions with a predisposition for the development of NHL are listed in Table 75-1. There are some genetic predispositions to the development of NHL, including specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele associations.10,11 Changes in the immune state, either immunosuppression or autoimmune disease with immune stimulation, can predispose to NHL. The immunosuppression can be primary (i.e., inherited as in severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome), secondary to retrovirus infection (HIV), or iatrogenic (after solid organ or bone marrow transplantation). The incidence of NHL in HIV-positive individuals has declined since the late 1990s, owing to highly effective antiretroviral therapy.12,13 Autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and celiac disease are also associated with an increased risk of NHL.14

TABLE 75-1 Causative Agents and Associated Conditions with a Predisposition to the Development of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

| Immunodeficiency |

| Congenital: Severe combined immunodefiencies, ataxia-telangiectasia |

| Acquired: Organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, HIV infection |

| Genetic Predisposition |

| Variants within 6q21 (HLA) |

| TNF G308A polymorphisms |

| Autoimmune Disorders |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis |

| Celiac disease |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Viral Agents |

| Epstein-Barr virus |

| Human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) |

| Herpesvirus type 8 |

| Hepatitis C |

| Bacteria |

| Helicobacter pylori (gastric lymphoma) |

| Chlamydia psittaci (orbital lymphoma) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi (cutaneous lymphoma) |

| Campylobacter jejuni (alpha heavy chain disease) |

| Drugs |

| Alkylating agents |

| Other immunosuppressive drugs |

| Pesticides |

| Phenoxyl herbicides |

| Organophosphate insecticides |

| Fungicides |

| Solvents and Other Chemicals |

| Benzene |

| Trichloroethylene |

| Hair dyes |

| Diet |

| N-nitroso compounds |

| Fat |

Infectious agents have been shown to be etiologic factors in NHL, such as Helicobacter pylori in gastric MALT lymphomas and Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphomas.15 There is a large variation in the Chlamydia positivity rate in orbital lymphomas depending on geographic location.16,17 The viruses that have been implicated include EBV,5 HTLV-1, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). HTLV-1 carriers have a 2% cumulative risk of developing adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, and this is a major public health problem in some parts of the world where the seropositivity rate is high.8 HHV-8 virus sequences have been implicated in primary effusion lymphomas and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Hepatitis C infection is also a predisposing factor for some B-cell lymphomas, often in association with essential mixed cryoglobinemia.18

Epidemiologic studies suggest an association with environmental factors, including industrial chemicals, rural residence possibly linking to use of pesticides or other agricultural chemicals, hair dyes,19 diet,20 and obesity.21 A small excess risk was also found in atomic bomb survivors for males but not for females,22 whereas minimal or no risk was found for low-dose x-ray exposures.

Prevention and Early Detection

With a better definition of environmental causative factors for NHL, it is expected that preventive strategies will be developed. For adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, initiatives are being implemented to reduce the disease burden in susceptible populations, the most important being the control of breast feeding to prevent maternal-fetal transmission of the HTLV-1 virus. Other promising areas of prevention currently include heightened awareness of potentially toxic agents and the development of improved products (chemicals and hair dyes). Genetic tests that aim to identify persons at higher risk of developing lymphoma are under investigation.11,23 For viral agents, the development of vaccines is under active study.24 For organ transplantation, avoidance of transplanting an EBV-positive donor organ into a EBV-negative recipient should reduce the risk of post-transplant NHL. For persons infected with HIV, effective combination antiviral treatments have contributed to a decreased incidence of lymphomas.13 The detection and eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach is an important strategy with potential to control or prevent MALT lymphoma25,26 and its transformation. As additional microorganisms and viruses other than the ones mentioned here are being discovered to play critical roles in the pathogenesis of some lymphomas,9,27 prevention and early treatment strategies will become increasingly important in the future.

Biologic Characteristics and Pathology

The present classification of NHL emphasizes lineage, function, and distinct clinicopathologic disease entities, with a liberal use of phenotypic and molecular techniques. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification, fourth edition,28 is shown in Table 75-2, (B-cell) and Table 75-3 (T-cell). The WHO classification recognized three major categories of lymphoid malignancies: B-cell, T-cell, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

TABLE 75-2 World Health Organization Classification for Mature B-Cell Neoplasms

NOTE: The italicized histologic types are provisional entities.

TABLE 75-3 World Health Organization Classification of Mature T-Cell and NK-Cell Neoplasms

NOTE: The italicized histologic types are provisional entities.

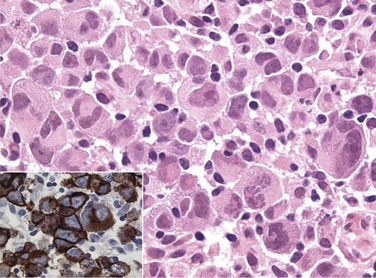

The diagnosis of the new pathologic and clinical entities continues to be based on morphology but is assisted by immunophenotyping and genotyping. The most common lymphoma entities were diffuse, large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (31%) and follicular lymphoma (22%). MALT/marginal zone lymphoma constituted 7.6% of cases, peripheral T-cell lymphomas, 7%, small B-lymphocytic, 6.7%, mantle cell, 6%, anaplastic large T/null cell, 2.4%, primary mediastinal large B-cell, 2.4%, and high-grade non-Burkitt’s and Burkitt’s, less than 3% of cases.29 Surface marker studies provide an objective basis for resolving difficult morphologic problems (Table 75-4). The lineage of the B-cell lymphomas is confirmed by pan–B-cell markers (CD22, CD19, CD20). T-cell lineage is evident from the presence of T-cell markers (CD3, CD2, CD7), and T-cell subset is determined from CD4 and CD8 analysis. Among indolent lymphomas, the CD5+, CD10−, CD23+ phenotype is characteristic of small lymphocytic lymphoma (chronic lymphocytic leukemia), the CD5−, CD10+, CD23± phenotype of follicular lymphoma, and the CD5−, CD10−, CD23− phenotype of MALT lymphoma (see Table 75-4). The CD5+, CD10−, CD23− phenotype is characteristic of mantle cell lymphoma. Among T-cell lymphomas the CD30+ phenotype is characteristic of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (Fig. 75-1), whereas CD56+ is associated with extranodal T-cell/NK-cell lymphoma of nasal type. Although surface marker analysis enhances the accuracy of the diagnosis, few surface marker characteristics are totally lineage specific. Ancillary cytologic and histologic techniques used to establish proliferative activity include labeling index, S-phase fraction, and Ki-67 antigen staining,30,31 which has been documented as a strong prognostic factor.

TABLE 75-4 Phenotypic Characteristics of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

| Lymphoma Type | Characteristic CD Antigen Profile |

|---|---|

| B-cell markers | CD19, CD20, CD22 |

| T-cell markers | CD2, CD3, CD4, CD7, CD8 |

| Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | CD30+ (Ki-1 antigen) |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma (B-CLL) | CD5+, CD10–, CD23+, B-cell markers |

| Follicular lymphoma | CD5–, CD10+, CD23±, CD43–, B-cell markers |

| Marginal-zone (MALT) lymphoma | CD5–, CD10–, CD23–, B-cell markers |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | CD5+, CD10±, CD23–, CD43+, B-cell markers |

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma occurs in older adults and commonly presents as generalized disease with spleen, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract involvement. Circulating lymphoma cells are frequently found in the blood. This type of lymphoma is associated with a characteristic immunophenotype (CD5+, CD10±, and CD23−) and genotype with t(11;14) translocation and BCL1 (CCND1/PRAD1) gene overexpression.28 Currently, advanced disease is not curable with chemotherapy. The median survival for patients with generalized disease is 4 to 6 years, and early use of high-dose therapy is promising.30,32,33 Expression of a microarray gene profile characterized by high proliferation,34 or a high Ki-67 growth fraction,35 confers a worse prognosis. Localized stage I and II mantle cell lymphoma is uncommon, and there are little data on curability. Existing datasets suggest that the survival of patients with localized mantle cell lymphoma is better than those with advanced disease and that RT has an important role in localized disease.36,37 Stage I and II mantle cell lymphomas may be curable.

T-Cell Lymphoma

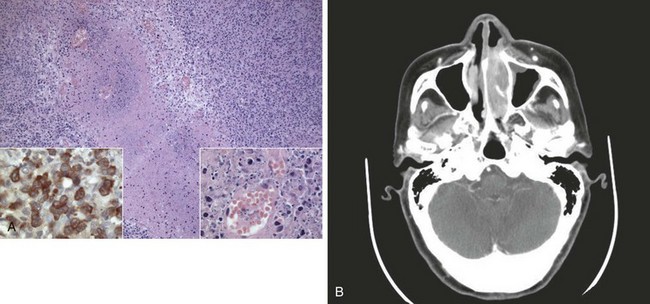

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of T-cell neoplasms that are more common in Asia38,39 and usually affect adults and are commonly generalized at presentation. An aggressive clinical course is typical; and although potentially curable, many T-cell lymphomas are resistant to current chemotherapy regimens. TCR gene rearrangements may be identified but this is not mandatory for diagnosis. Specific subtypes of T-cell lymphoma to consider include extranodal natural killer (NK)-cell/T-cell lymphoma of nasal type and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), previously called malignant histiocytosis of the intestine. This latter disease (EATL) usually involves the jejunum and in approximately 50% of cases is associated with a history of celiac disease.40 Most EATLs express the human mucosal lymphocyte-1 (HML-1) antigen, supporting an origin from the intraepithelial T cells of MALT. EATLs are high-grade pleomorphic large cell lymphomas associated with a very poor prognosis. The entity of NK-cell/T-cell lymphoma of nasal type includes disorders previously known as lethal midline granuloma and nasal T-cell lymphoma. It is characterized by an angiocentric and angioinvasive infiltrate28,41 (Fig. 75-2), with CD56-positive (T-cell/NK-cell) immunophenotype and is characteristically EBV positive. This disease responds poorly to chemotherapy and usually follows an aggressive course.42,43,44 Other rare presenting sites may include skin, lung, testis, and central nervous system (CNS).

The WHO classification, although aimed to classify distinct disease entities and acknowledging the uniqueness of certain presentations (e.g., the T cell lymphomas just cited), does not always consider the presenting site of the lymphoma. Recent evidence strongly suggests that the presenting site is an important factor for primary extranodal lymphomas. Examples include different causes for MALT lymphoma arising in different sites that are associated with differences in relapse rate.45 Similar histology lymphomas may have distinct outcomes (e.g., diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving the brain and thus with a poor prognosis) that are now clearly identified in the fourth edition of the WHO classification versus stomach or Waldeyer’s ring structures, which have a good prognosis.46 With further understanding of etiology and pathogenesis of lymphomas, future modifications to classification of these diseases are expected.

Molecular Biology

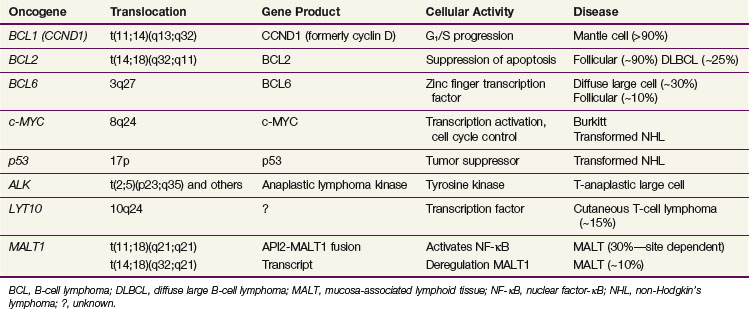

The various pathologic subtypes of NHL are characterized by distinctive nonrandom genetic alterations. The categories of molecular lesions include chromosomal translocations with activation of oncogene as the most commonly observed abnormality (e.g., BCL2 in follicular lymphomas), oncogenic viruses (e.g., EBV and HTLV-1), and inactivation of tumor suppression gene by chromosome mutation or deletions (e.g., TP53). Some of the well-characterized genetic lesions with their corresponding pathologic subtype are presented in Table 75-5. Many of the genetic lesions involve the translocation of an oncogene to a juxtaposition of the immunoglobulin gene (in B-cell lymphomas) or T-cell receptor gene (in T-cell lymphomas). Locations of breakpoints usually occur at the joining (J) or switch (S) sequences involved in antigen receptor gene rearrangement as part of normal lymphoid development to produce antigenic variation. The causes of these translocations are largely unknown, but once established these lesions appear to be highly specific for the type of malignant lymphoma that they characterize.

BCL2

The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation involving BCL2 is the most common chromosome translocation in NHL. BCL2 encodes a 26-kd membrane protein that controls and prevents cellular apoptosis. The gene is translocated to a J segment of the IGH gene on chromosome 14, giving rise to deregulation of BCL2, with the result being the inhibition of apoptosis of B cells. This lesion is present in more than 90% of follicular lymphomas and in transformed follicular lymphomas.47 In the latter situation, additional genetic lesions are acquired (TP53 mutation, deletion of chromosome 6q27, MYC) in parallel with more rapid growth and an aggressive clinical course. The TP53 mutation is associated with a poor survival rate in aggressive B-cell lymphomas, independent of the predictive effects of the International Prognostic Index (IPI).48 The t(14;18) translocation is also found in 20% of de novo DLBCL and appears to be an unfavorable prognostic factor.

BCL6

The BCL6 gene located on 3q27 is translocated in 40% of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.49,50 Reciprocal translocations can involve a number of other chromosomal locations, including 14q32 (IGH), 2p11 (IGK), and so on, all juxtaposing to 3q27.51 BCL6 is thought to mediate the DNA-binding activity of a number of zinc-finger transcription factors and characterizes the germinal center B-cell gene signature in microarray studies.52 The presence of the BCL6 translocation in DLBCL carries a favorable prognosis, in comparison with those carrying BCL2 who have a worse outcome and those with neither translocation who have an intermediate prognosis.49,53

MYC

The MYC oncogene, located on chromosome 8q24, regulates cellular proliferation and differentiation. Its translocation is seen in 100% of Burkitt’s lymphomas typically to chromosome 14q32 (IGH), less commonly to 2p11 (IGK) and 22q11 (IGG). EBV infection is responsible for and can be documented in almost all cases of endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma and about 30% of the sporadic cases.51,54 Aberrations of 8q24 can also be seen in follicular lymphoma, DLBCL, and mantle cell lymphoma and is characterized by transformation or progression of the disease, generally denoting a poor prognosis.55,56

Other Chromosome Translocations

The t(2;5)(p23;q35) translocation characterizes anaplastic large cell lymphomas of T-cell origin. This translocation involves the fusion of the NPM1 (nucleophosmin) gene on 5q35 and the ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) gene on 2p23.28 Others involving ALK-2p23 include t(1;2)(q25;p23), Inv2 (p23q35), and many others.28 T-cell lymphomas may have 14q11 abnormalities involving the T-cell receptor-alpha gene. In MALT lymphomas, characteristic genetic abnormalities can include trisomy 357 and chromosomal translocations t(11;18)(q21;q21),58 t(1;14)(p22; q32),59 and t(14;18)(q32;q21)60 (see Table 75-5).

Microarray Gene Profiling Studies

Gene-expression studies have been increasingly utilized to characterize various lymphomas. Microarray analysis of cDNA (the “lymphochip”) using hierarchical clustering techniques initially classified DLBCL into two groups.61 One expressed “germinal center B-cell–like” genes (GCB signature), such as MYBL1, LMO2, JNK3, CD10, BCL6, CREL, and BCL2, whereas the other expressed “activated B-cell–like” genes (ABC signature), such as CCND2, IRF4, FLIP, NF-κB, and CD44. For patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy in the pre-rituximab era, the 5-year survival for the GCB group was 60%, compared with the ABC group of 35%, whereas that for a type 3 group was 39%.52 Based on a selection of the most prognostic genes, either a larger series of 17 genes52 or condensing further to three immunostains for CD10, BCL6, and MUM1,62 studies have shown that gene expression profiling provides additional prognostic information in addition to the clinical IPI scores.52,62 Additional studies using oligonucleotide microarrays and a different analysis technique have also successfully identified two categories of patients with very different survival rates (70% vs. 12%) in DLBCL.63 Gene profiling of the nonmalignant infiltrating cells in the tumor has also been found to be prognostic in DLBCL, whether treatment included rituximab or not.64 The “stromal-1” group reflected extracellular matrix deposition, and histiocytic infiltration had a better prognosis than the “stromal-2” group, which reflected tumor angiogenesis activity.64 Presently, the microarray assays are still not widely available. Other examples of microarray studies discovering significant findings correlating with clinical outcome include primary mediastinal B-cell lymphomas,65 Burkitt’s lymphoma,66,67 mantle cell lymphoma,34,68 and follicular lymphoma.69 In the case of follicular lymphoma it is of interest that it was the gene signature of the nonmalignant infiltrating immune cells, rather than the malignant cells, that had the prognostic effect.69 It is likely that within the next decade most lymphomas will have their distinct genetic signatures identified. In addition to its usefulness in obtaining an accurate diagnosis (e.g., between DLBCL and Burkitt’s lymphoma),66 and enhancing prognostication, these techniques could also be helpful in the study of minimal residual disease, that is, the detection of a small number of morphologically normal but genetically monoclonal population of malignant cells. The most important aspect of this evolving field is the insight provided into the molecular events underlying malignant transformation, cell cycle regulation, signal transduction, and cell death. Characterization of these mechanisms opens up the potential for novel therapeutic strategies, for example, targeting small molecules such as NF-κB.70

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging Classification

Patient Evaluation

The goal of evaluation is to determine disease extent and bulk and its anatomic distribution and to ascertain normal organ and immune function relevant to the choice of therapy. With the diverse presentation of lymphomas, the recommended investigations may vary,71 but the following procedures serve as minimum recommended investigations (Table 75-5). Additional tests may be necessary based on such factors as the presenting complaint, the subtype of lymphoma, and predilection of organ involvement (e.g., brain and cerebrospinal fluid).

Imaging Studies

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis is the minimum standard today. The radiographic assessment of the extent of extranodal involvement is of particular importance in the planning of RT, since 50% of localized lymphomas occur in extranodal sites. Other radiographs should be obtained based on the actual or suspected organ involved. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated in delineating areas of suspected involvement of bone or CNS, such as spinal cord and epidural space, brainstem, base of skull and cavernous sinuses, and leptomeninges. The role of routine MRI for the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis has not been established. Bone scintigraphy is not recommended as a routine test except in patients with bone pain or those presenting with localized bone lymphoma. Total-body scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is now a standard staging procedure in many countries and is used also to document response to therapy. FDG-PET has replaced gallium-67 scans in clinical practice, and nonrandomized studies comparing the two imaging modalities in terms of sensitivity concluded that FDG-PET is more sensitive than gallium-67 (100% vs. 71.5%).72–74 Whole-body FDG-PET has been shown to have a high predictive value for differentiating active from necrotic residual masses in lymphomas75,76 and has been incorporated in the revised International Working Group response criteria.77 The category of “complete response, unconfirmed” has been eliminated because PET-negative patients are now classified as complete responders and those with PET-positive disease will be partial responders. Consensus guidelines regarding standardization of PET reporting has also been published by the International Harmonization Project in lymphoma.78 Mediastinal blood pool activity was recommended as the reference background activity to define PET positivity for a residual mass 2 cm or larger in maximum diameter. A smaller residual mass or a normal-sized lymph node is considered positive if its activity is above that of the surrounding background.78 Increasing evidence also suggest that persistent FDG-PET activity after one to four cycles of chemotherapy confers a worse prognosis.79 In a systematic review of seven studies, interim FDG-PET in DLBCL has a sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.87.79

Staging Classification

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) have endorsed the use of the Ann Arbor classification for staging of NHL. The Ann Arbor staging classification has been used for more than 40 years.80,81 In the Ann Arbor system, Waldeyer’s ring, thymus, spleen, appendix, and Peyer’s patches of the small intestine are considered as lymphatic tissues and involvement of these areas does not constitute an “E” lesion, originally defined as extralymphatic involvement. However, because of the unique pathologic and clinical characteristics of primary lymphoma affecting these organs, most clinicians consider them as separate clinical entities and report their involvement as extranodal presentation. The Ann Arbor classification differentiates locoregional from widespread lymphoma and documents anatomic extent of disease and B symptoms, but it is not optimal for describing the extent of local disease, invasion of adjacent organs, tumor bulk, or multiple sites of involvement within one organ (e.g., skin, gastrointestinal tract). Several modifications to the Ann Arbor classification have been proposed in the past. In gastric lymphoma, substaging of stage I to reflect the depth of the stomach wall penetration has been suggested. In stage II disease, distinction of involvement of the immediate nodal region (II1) versus more extensive regional lymph node involvement (II2) has been found to be of prognostic significance in primary gastrointestinal lymphomas.82,83 Currently, the Ann Arbor staging classification supplemented by description of prognostic factors, including tumor bulk, hematologic and biochemical parameters, sites of involvement, and pathology, remains the basis for patient assessment.

| General |

|

• History, including systemic symptoms (unexplained fever, night sweats, weight loss > 10% of body weight), risk factors for HIV infection

|

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood (cell) count; CT, computed tomography; FDG-PET, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-labeled positron emission tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

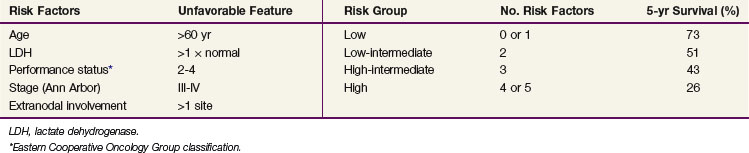

Prognostic Factors

Although the anatomic extent of disease reflected by Ann Arbor stage is an important prognostic factor, many other factors are known to influence the outcome in patients with NHL. They include histologic type, phenotype (B cell vs. T cell),38,39 tumor bulk,84,85 number of involved nodal regions and extranodal sites, proliferation indices (S-phase fraction, Ki-67 antigen), as well as age, gender, and performance status86 (Table 75-7). The IPI was derived from patients with aggressive lymphomas treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in phase II and III trials. Based on factors identified in multivariate analysis, the IPI is based on the patient’s age, serum LDH level, performance status, and number of involved extranodal sites86 (Table 75-8). Patients are grouped according to the number of adverse factors, which are age older than 60 years, stage III or IV disease, abnormal LDH level, performance status greater than 1, and more than one involved extranodal site. Patients in the low-risk group (none to one adverse factor) treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy ± RT had a 73% 5-year survival; in the low-intermediate group (two adverse factors) it was 51%, in the high-intermediate group (three adverse factors) it was 46%, and in those in the high-risk group (four or five adverse factors) it was 26%.86 A similar pattern of decreasing survival with an increasing number of adverse factors was observed in younger patients. The validity of the IPI has been confirmed in a population of patients with T-cell lymphomas.87 The IPI was less useful in indolent lymphomas,88 and a different index has been proposed: the FLIPI (follicular lymphoma IPI).89 The FLIPI is based on the following adverse prognostic factors: age older than 60 years, stage III or IV disease, abnormal LDH level, five or more involved nodal areas, and hemoglobin level less than 120 g/L.89 A subsequent study (the F2 study) proposed a modification of FLIPI (FLIPI-2) using the following adverse prognostic factors: age older than 60 years, bone marrow involvement, abnormal β2-microglobulin level, maximum tumor diameter greater than 6 cm, and hemoglobin level less than 120 g/L.90 For mantle cell lymphoma in advanced stages there is a yet another proposed prognostic index known as the mantle IPI (MIPI), based on the following adverse prognostic factors: older age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, LDH level, and the leukocyte count.35 Other prognostic factors include the presence of BCL6 rearrangement, high levels of BCL2 protein secretion,91 survivin expression,92 and TP53 mutation.48 The prognostic significance of gene profiling with microarray studies was discussed previously. In addition to the genetic and phenotypic factors, the presenting site of lymphoma has prognostic implications; for example, lymphoma presenting in testis, ovary, eye, CNS, and liver has a particularly adverse prognosis, whereas orbital and skin lymphomas generally have a good prognosis.

| Factor | Favorable | Adverse |

|---|---|---|

| Histologic type | Low-grade MALT | Diffuse large cell Mantle cell |

| Immunophenotype | B-cell | T-cell, NK-cell |

| Tumor bulk | <5 cm | >10 cm |

| Ann Arbor stage | I, II | III, IV |

| Symptoms | Asymptomatic | B symptoms |

| Proliferative indices | S-phase fraction <5% | High % S-phase |

| Ki-67 <80% | Ki-67 >80% | |

| Age | <60 yr | ≥60 yr |

| LDH | Normal level | Abnormal level |

| β2-microglobulin | Normal level | High level |

| HLA-DR expression | Present | Absent |

| CD44 expression | Low | High |

| BCL2 protein | High | Low |

| BCL6 rearrangement | Present | Absent |

| Site of extranodal presentation | Orbit, skin, tonsil | Brain, testis |

HLA, human-leukocyte antigen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; NK, natural killer.

Principles of Management

Radiation Therapy

RT techniques and prescriptions are discussed in detail later in this chapter. It is important to note that when RT follows chemotherapy in combined-modality therapy protocols, RT is usually started 4 to 6 weeks after the last course of chemotherapy to allow recovery of blood cell counts and to minimize the drug-radiation sensitization effect. McManus and colleagues93 documented an increased risk of RT treatment interruption due to both thrombocytopenia and neutropenia with concurrent chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy

Frequently used chemotherapy regimens for NHL are listed in Table 75-9. These include single agents used for indolent lymphoma and anthracycline-containing regimens potentially curative for diffuse large cell B-cell (e.g., CHOP-rituximab) or T-cell lymphomas and regimens used for patients with recurrent disease. For high-grade lymphoblastic and Burkitt’s lymphomas, dose-intensive protocols are used with concurrent intrathecal chemotherapy for CNS prophylaxis.94,95 In a combined-modality approach for localized disease it is useful to deliver the chemotherapy first to promptly treat potential systemic microscopic disease and to reduce the bulk of the known local disease. In this setting, the goal of chemotherapy is to facilitate a response but not necessarily obtain a complete response at the local site. Quite often, residual thickening or a minimal mass of tissue remains by palpation or imaging, which should not deter from proceeding with the original RT plan.

TABLE 75-9 Common Chemotherapy Regimens for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

| Indolent Lymphoma | Histologically aggressive Lymphoma | Salvage Therapy |

|---|---|---|

Management of Localized (Stage I And II) Disease

Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma and Follicular Lymphoma

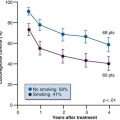

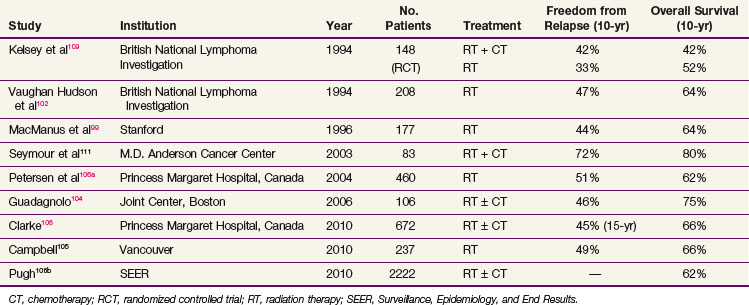

Small lymphocytic lymphoma is a manifestation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is rarely, if ever, localized. It is managed as for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and not further considered here. For follicular lymphoma, stage I and II presentations account for approximately 30%.90,96 With the availability of sensitive techniques to detect subclinical disease (e.g., FDG-PET and BCL2 by polymerase chain reaction), some patients with stage I and II disease may be upstaged97 or may have a clonal population of B cells identified in the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow.98 Localized RT produces excellent local disease control (>95%) and a freedom from relapse rate of 50% at 10 years. Data from multiple institutions99–104,105,106 documented comparable results with over 90% local control and 10-year relapse-free rates of approximately 50% with overall survival (OS) of 70%. A number of representative single-institution results published in the past decade are summarized in Table 75-10. At Stanford University Medical Center the use of extended-field, subtotal or total lymphoid irradiation gave a higher relapse-free rate of 67% at 10 years, compared with 36% for patients who had treatment to only one side of the diaphragm. However, because the OS was similar,99 extended-field RT has been abandoned. Prognostic factors predictive of a high risk of relapse included age, extent of disease as reflected by stage, systemic symptoms, and tumor bulk. Follicular grade 2 is also an adverse factor for relapse. The addition of chemotherapy (e.g., with CVP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) tested in several randomized trials in the 1970s did not confer an OS advantage.107–110 Phase II trials of patients with poor prognostic factors (i.e., constitutional symptoms, high LDH, follicular large cell histology) treated with combined-modality therapy (e.g., CHOP-bleomycin: cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin [doxorubicin], vincristine [Oncovin], prednisone and bleomycin) documented a 10-year failure-free rate and OS of 73% and 82%, respectively, suggesting benefit for combined-modality therapy.111 With no definitive data showing a survival advantage with combined-modality therapy, IFRT is currently the preferred treatment for most follicular lymphomas. Grade 3B follicular lymphoma behaves similarly to DLBCL, and patients with this tumor should be treated with combined-modality therapy. Given the benefits of adding rituximab to either CVP or CHOP in patients with III and IV disease, it is logical to incorporate rituximab into these regimens for early-stage disease. A study of selected patients with I or II disease who were observed with no initial treatment showed that 38% required therapy after a median of 86 months.112 However, a policy of observation is not appropriate for all patients because a plateau in the disease-free survival (DFS) curve for the patients treated with irradiation beyond 15 years has been observed, suggesting that a proportion of patients are cured.99,105,106

TABLE 75-10 Localized (Stages I to II) Follicular Lymphoma, Treatment Results with Radiation Therapy ± Chemotherapy

There is marked variation in RT practice for localized indolent lymphoma.71,113 RT target volume varies widely.99,105,114,115 IFRT is currently considered as the standard approach. The involved field is currently being redefined in favor of gross tumor volume/clinical target volume–based treatment planning, which has also yielded excellent results.105 With moderate doses of radiation (30 to 35 Gy, over a 4-week period), the local control rate is over 95%. Relapse occurs almost exclusively in distant unirradiated sites. Treatment at the time of recurrence requires chemotherapy, although RT is also very useful in selected cases. High response rates are observed even with a low total dose of 4 Gy (2 × 2 Gy).116,117,118 Because of the indolent nature of these lymphomas, long-term follow-up is required to test the effects of any new treatment approaches on survival. The relative rarity of localized disease, the long follow-up required, and competing mortality from unrelated causes form significant barriers to conducting clinical trials in this disease.

Marginal Zone Lymphoma, Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Type

MALT lymphomas are usually indolent B-cell tumors that present as stage I to II disease in 70% to 90% of cases. They are characterized by infiltration of mucosa, lymphoepithelial lesions, and clonal proliferation of centrocyte-like B cells.28,57 MALT lymphomas arise most often in the stomach, orbit, thyroid, salivary glands, breast, lung, skin, and bladder.57 The cause of gastric MALT lymphoma is linked to infection with Helicobacter pylori. Association of Chlamydia psittaci with orbital adnexal MALT lymphoma has been documented, with marked geographic variation in different parts of the world.15,17,27 Cutaneous MALT lymphoma has been associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection in Europe119 but not in the United States.120,121 Although the majority of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma respond to antibiotic therapy, the t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation has been reported to be associated with resistance to H. pylori therapy.122,123 The fact that this translocation is also found in MALT lymphoma arising from nongastric sites such as lung and orbit58 suggests a common genetic mechanism in the development of disease in these sites for some patients. IFRT with doses of 25 to 35 Gy results in more than 95% local control, and a significant proportion of patients may be cured.45,124–126 Although MALT lymphomas are usually indolent, transformation into aggressive large B-cell lymphomas occurs. The risk factors for future transformation have not been confirmed. Current experience with MALT lymphomas shows a tendency to localized disease and cure with local therapy.45,127 The nodal counterpart of MALT, also known as monocytoid B-cell lymphoma, occurs in the older age-group and is similar morphologically and immunologically to MALT lymphoma.128

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

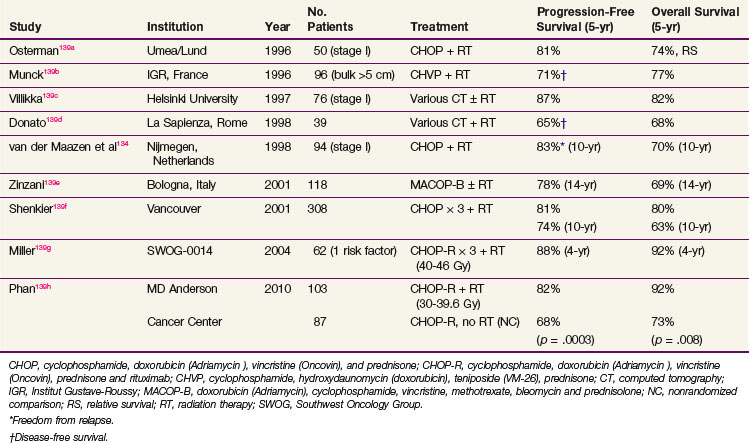

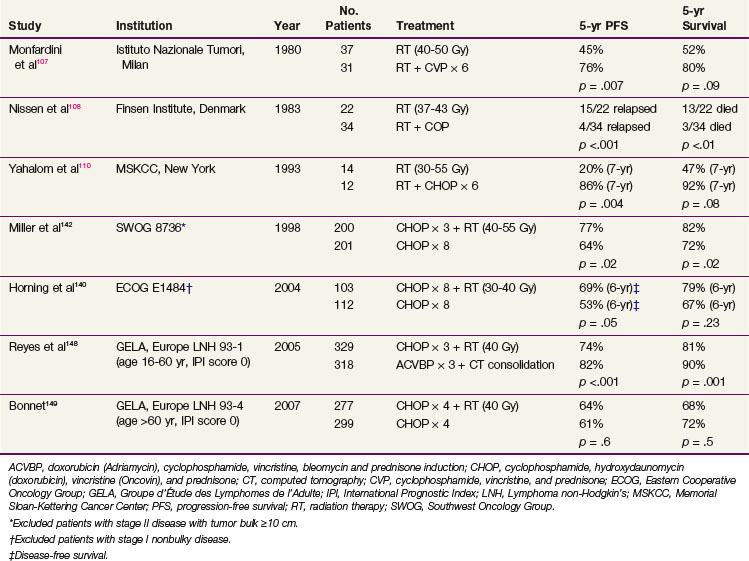

The treatment of localized DLBCL has evolved from the use of RT alone to the routine use of combined-modality therapy. Patients with pathologic stage I disease have 10-year relapse-free rates of approximately 90% with RT alone.129,130 Similarly, patients with stage IA or IIA disease with favorable clinical attributes treated with RT alone to a dose of 35 Gy achieved a 77% relapse-free rate at 10 years.131 In the early 1980s, several phase III trials have shown the superiority of combined chemotherapy and RT.107,108 Combined-modality therapy became the standard approach, with the administration of three to eight courses of doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy followed by IFRT. Brief chemotherapy with three courses of CHOP followed by RT (30 Gy or equivalent) produced excellent results in patients with nonbulky (<10 cm) stage I to II disease with a 10-year PFS of 74% and OS of 63% after a median follow-up of 7.3 years.132 Other investigators achieved similar results with four to six cycles of CHOP and RT,133,134 alternating CHVP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin [doxorubicin], teniposide [VM-26], prednisone) with RT,135 or four cycles of ProMACE/MOPP (prednisone, methotrexate [with leucovorin rescue], doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, etoposide/mechlorethamine, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, prednisone) and RT.136 Within the past decade, rituximab has been added to CHOP (CHOP-R) because it provided improved disease control compared with CHOP alone both in advanced-stage disease137,138 and localized disease.138,139 Representative combined-modality therapy results published in the past 15 years are presented in Table 75-11.

TABLE 75-11 Localized (Stages I and II) Histologically Aggressive Lymphoma, Treatment Results with Combined-Modality Therapy

With the success of chemotherapy in advanced NHL, the role of routine RT in localized disease is being questioned and trials of chemotherapy alone for localized nonbulky DLBCL have been conducted. The results of two large phase III trials testing chemotherapy alone versus combined-modality therapy are shown in Table 75-12. In the ECOG trial (E1484), 345 patients with stage I and II disease (including bulky tumors) were treated with eight courses of CHOP chemotherapy and randomized to receive consolidation IFRT or no further treatment.140 For those with complete response randomized to RT, the dose was 30 Gy, whereas all patients with a partial response received 40 Gy. With an intent-to-treat analysis, the 6-year DFS was 53% in the CHOP trial arm and 69% in the combined-modality therapy trial arm (p = .05). The OS at 6 years was 67% for CHOP alone and 79% for combined-modality therapy (p = .23).140 Patients with a partial response to CHOP received RT, and their 6-year failure-free survival was 63%, similar to those achieving a complete response to CHOP. This trial confirmed the benefit of IFRT in patients who received CHOP in terms of disease control. However, no OS benefit was evident in this trial but the trial had inadequate power to detect a clinically important (10%) survival difference. Data from 13,420 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, End-Results (SEER) database for years 1988 to 2004 showed that the use of radiation was associated with a survival advantage over those who did not receive radiation (absolute improvement of 3.7% at 15-year follow-up).141 However, chemotherapy details were not available from this database.

TABLE 75-12 Localized (Stages I to II) Aggressive Lymphoma, RCTs of CMT versus RT and CMT versus Chemotherapy

The Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) trial included 401 patients with stage I and II nonbulky disease (tumor mass <10 cm maximum diameter) and compared treatment with eight courses of CHOP versus three courses of CHOP followed by IFRT.142 The radiation dose was 40 Gy with a boost to 50 Gy for partial responders to three courses of CHOP. Patients treated with combined-modality therapy had superior 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) (77% vs. 64%, p = .03) and OS (82% vs. 72%, p = .02).142 The adverse risk factors included stage II disease, age older than 60 years, increased LDH, and ECOG performance status of greater than 1. This raised a concern that patients with adverse prognostic factors might have had inadequate chemotherapy in the combined-modality therapy trial arm. The decision to use fewer than six courses of chemotherapy should be based on known prognostic factors that predict for tumor burden.86,142,143,144 We currently recommend that patients with limited risk factors (i.e., nonbulky disease, nodal stage I, normal LDH, no B symptoms, and good performance status) be treated with three courses of CHOP-R followed by IFRT. Patients with more than one risk factor should be approached with a longer course of chemotherapy (six cycles) and IFRT. When possible, brief chemotherapy with RT is preferred132,139 because this approach likely reduces the cardiac toxicity of full courses of doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy.106b,145 When FDG-PET becomes negative after chemotherapy, the risk for residual disease may remain significant147 and we continue to recommend consolidative RT in these patients when the initial plan was combined-modality therapy.

The general principles of RT in combined-modality therapy protocols is to use IFRT, to a dose of 30 to 35 Gy over 3 to 4 weeks. Additional phase III trials from the Groupe d’Étude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) have been reported.148,149 A benefit for combined-modality therapy was not demonstrated when compared with chemotherapy alone (see Table 75-12). The GELA LNH 93-4 trial studied patients older than age 60, with no IPI factors and compared four cycles of CHOP versus four cycles of CHOP and RT.149 It might well be that four cycles of CHOP is inadequate therapy for this group of patients and the addition of RT cannot compensate for suboptimal chemotherapy. The GELA LNH 93-1 trial showed that for patients younger than the age of 60 years, an intensive chemotherapy regimen (ACVBP—doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone), followed by sequential consolidation treatments) gave better results and more favorable event-free survival and OS when compared with three cycles of CHOP and RT.148 Whether the addition of RT is beneficial to chemotherapy alone when regimens more intensive than CHOP (e.g., CHOP-R or ACVBP) are used awaits further testing in phase III trials.

Other Histologic Subtypes

Less common, but distinct clinicopathologic entities including peripheral T-cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma may present as localized disease. At present, the treatment strategies for these entities are similar to those for DLBCL, with the use of combined-modality therapy (with rituximab added for CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas). In studies of a small number of patients with stage I to II mantle cell lymphoma, the use of an RT-containing regimen was associated with an improved disease control or survival.37,150 As the knowledge regarding their clinical behavior, genetic origin, and etiology evolve, innovative therapy will become available for these specific diseases over the next decade.

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma and Burkitt’s Lymphoma

These lymphomas usually present as advanced-stage disease. Infrequently, localized presentations occur and the treatment in such cases is similar to that for advanced-stage disease. Chemotherapy protocols with high dose intensity including CNS prophylaxis are required for best results. Commonly used regimens are described by Magrath and colleagues151 and Bernstein and associates152 for Burkitt’s lymphoma, and hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin [Adriamycin], dexamethasone)153,154 is used for lymphoblastic or Burkitt’s lymphomas. CNS prophylaxis including intrathecal chemotherapy, with or without cranial irradiation, is a common element in these protocols.

Management of Advanced (Stage III And IV) Disease

Follicular Lymphomas

The advanced-stage follicular lymphomas are not cured with current approaches.155,156 For asymptomatic patients, observation may be appropriate. Symptomatic patients require chemotherapy to induce complete response, and RT is reserved for control of local symptoms. In the Stanford University Medical Center report,157 initially observed patients required treatment after a median interval of 3 years. Their OS was 73% at 10 years. Spontaneous regression of disease lasting a median of 13 months was observed in 23% of cases. Patients selected to undergo intensive therapy (n = 37) in a phase II study had 10-year survival of 86%.155 Histologic transformation to a more aggressive histology (usually DLBCL) occurred in 60% at 6 years in one series158 and in 31% at 10 years in another.159 Deferred therapy tested in a randomized study showed no effect on survival (78% vs. 70% for early treatment, p = .24).160 Extensive nodal irradiation has been attempted in the past, and the available data indicate a high probability of disease control within radiation fields.98,114,115 However, with the long natural history of this disease and the selection of patients submitted to protocol treatment, it is difficult to ascertain whether extensive lymphatic irradiation improves survival or results in cure. Other strategies for the treatment of indolent lymphoma include total-body irradiation (TBI),161–163 purine analogues,164,165 rituximab-chemotherapy combinations,31,166–168 radioimmunotherapy,169–172 and high-dose chemotherapy with RT and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.155,173–176 Newer agents with activity include bortezomib or bendamustine.177 Postchemotherapy maintenance with rituximab has also been shown to improve outcomes.178 Favorable responses have been documented for each of these approaches, but no firm evidence for cure has been evident. Investigators who undertook a meta-analysis of trials using interferon-alfa concluded that improvement in survival and remission duration was seen when this agent was used at a dose of 5 mU or more (or ≥36 mU/month) in combination with relatively intensive chemotherapy.179

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas

CHOP alone results in a complete response rates of 50% to 55% and long-term cure rates of 30% to 35%.180 The CHOP-R regimen is currently considered as the standard chemotherapy for advanced (stage III and IV) disease.137,138 To date, “adjuvant” RT following a complete response to chemotherapy has not been shown to improve the OS in advanced-stage NHL.181,182 On the premise that bulky sites of lymphoma are more difficult to control with chemotherapy alone, some centers selectively administer adjuvant RT to initially bulky sites after complete or incomplete response to chemotherapy.183,184 A randomized trial of 166 patients from Mexico giving RT to sites of residual disease (defined as <5 cm) after chemotherapy suggested an improved 10-year PFS (86% with RT vs. 32% without RT, p <.001) and OS (89% with RT vs. 58% without RT, p <.001).185 Confirmatory trials are required before this strategy can be routinely recommended, and whether FDG-PET findings may assist with decision making in the setting of localized metabolically active residual disease after chemotherapy. However, adjuvant RT is often useful to prevent local relapse in sanctuary sites. RT to the uninvolved testis in primary testicular lymphoma prevents relapse in the contralateral testis.186 Cranial irradiation is used to prevent CNS relapse in high-risk cases, although the value of cranial RT in patients treated with intrathecal chemotherapy has not been confirmed in a randomized trial. In addition, RT has value as a palliative modality and is discussed later.

Early high-dose therapy with bone marrow transplantation had been an attractive approach but when tested in patients with adverse prognostic factors showed no definite advantage over standard chemotherapy alone.187–189 A French trial (GELA LNH 93-3) in patients at high and at high-intermediate risk actually showed a worse outcome for the autologous stem cell transplantation arm of the trial.190 The GELA trial did not use RT, despite the inclusion of patients with stage I and II disease (some with bulky disease) that accounted for 30% to 40% of the patients studied.189,191 At this time, early bone marrow transplantation as part of initial therapy cannot be considered standard192–195 but is reserved for patients with refractory or relapsed disease.

Other Histologic Subtypes

Distinct clinicopathologic entities such as peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and mantle cell lymphoma are currently treated similar to DLBCL. ALCL has a better prognosis than PTCL. Because standard chemotherapy results in a lower cure rate for PTCL and mantle cell lymphoma, new approaches have been advocated, including the incorporation of new drugs196–198 and consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation.30,33

Assessment of Response and Follow-Up

Cure requires the ability to eradicate disease; therefore, the key is to attain complete remission with the initial treatment plan. In patients treated with RT alone, response is usually assessed 4 to 6 weeks after the completion of therapy. Because the RT dose fractionation schedule is determined before treatment and is usually based on information regarding dose-response relationship and tolerance of tissues within the treatment volume, the presence of residual disease at the end of the treatment course is not an indication for additional RT. The assessment of response includes examination of the organ of presentation, repeat imaging studies if indicated, and a general examination to rule out disease progression. In patients treated with chemotherapy or combined-modality therapy in which chemotherapy is used first, the response is assessed following one or two courses of chemotherapy and every 1 to 2 months thereafter. Chemotherapy is usually continued for two courses beyond attainment of complete remission. FDG-PET is useful in determining completeness of response, as discussed earlier. However, it must be emphasized that FDG-PET cannot detect residual microscopic disease reliably.147 For cases in which the standard therapy is combined-modality therapy, a negative PET after chemotherapy does not imply that RT can be safely omitted.147 Although most recurrences in patients with aggressive lymphoma occur within 2 to 3 years after the diagnosis, late relapse occurs. Accordingly, prolonged follow-up is indicated. Some tumor locations pose special problems in follow-up assessment. For example, primary bone lymphoma often has persisting radiologic and MRI abnormalities after treatment, and bone scintigraphy will show changes that cannot distinguish active disease from bone healing and remodeling. Residual mediastinal abnormalities are common, particularly if a bulky mass was present before treatment. Resolution of FDG avidity is helpful in such cases. Although interim FDG-PET activity after one to four cycles of chemotherapy confers a worse prognosis,79 the sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.8779 are not high enough to routinely base clinical decisions to intensify or attenuate treatment based on such findings alone.

Salvage Therapy and the Role of Radiation Therapy

For patients with relapsed or chemotherapy-refractory large cell lymphoma, RT alone is rarely curative. However in highly selected cases, durable long-term control of disease can be achieved with salvage RT.199 Conventional salvage chemotherapy also has a very low curative potential. Common salvage regimens include DHAP,200 mini-BEAM,201 ESHAP,202 ICE ± rituximab,203,204 and GDP (see Table 75-9 for expansion of drug names).205 For patients with chemotherapy-sensitive disease, high-dose therapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is of benefit. A phase III trial by the Parma study group tested the role of high-dose therapy in 109 patients. Those demonstrating a response to two cycles of DHAP chemotherapy were randomized to four further courses of DHAP, versus a conditioning regimen of BEAC (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide) followed by autologous bone marrow transplantation. The 5-year event-free and OS for the transplant arm were 46% and 53% versus 12% (p = .001) and 32% (p = .038) for the conventional DHAP arm, respectively.206 RT was given twice daily to a dose of 26 Gy in 20 fractions as a protocol treatment for patients with tumor bulk greater than 5 cm at the time of relapse in the transplant arm and to 35 Gy in 20 fractions in the conventional chemotherapy arm. There was a trend favoring the RT patients, with a lower relapse rate in the transplant group (8/22 RT patients experienced relapse vs. 18/33 nonirradiated patients, p = .19), and no obvious difference in the conventional chemotherapy group (10/12 RT patients with relapse vs. 35/42 nonirradiated patients with relapse). Although this trial was not designed to examine the role of RT in the salvage setting, it lends support to the use of RT for bulky disease when incorporated into a salvage treatment plan that includes high-dose therapy. The role of RT in bulky disease after partial response to salvage chemotherapy deserves further study in a randomized trial in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Until such evidence is available, we recommend routine RT to sites of bulky disease, in sequence with salvage chemotherapy, and also RT to sites of incomplete response to chemotherapy.207,208,209,210,211

Moderate doses of 30 to 35 Gy should be the goal with individualization of the treatment plan in regard to the exact target volume (IFRT is preferred) and the timing of RT in relation to chemotherapy and transplant to facilitate the collection and harvesting of stem cells and minimize treatment-related toxicity. For example, if large RT fields are required, RT should be given after stem cell harvesting and preferably before the transplant. Thoracic RT that will include significant volumes of lung tissue is less risky if given after transplantation.212,213 In general, the principles of RT should be to treat the most likely site of relapse or progressive disease. The decision to treat with RT is influenced by the distribution and location of the disease. The spinal cord may be more radiation sensitive in the post-transplant setting, and there are case reports of radiation myelopathy with conventional fractionated doses of 40 to 45 Gy.214–216

Total-Body Irradiation

The use of TBI as part of the conditioning regimen before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for lymphomas is premised on its successful role in the treatment of acute leukemias.217 Although TBI is given for both tumor cell kill and immunosuppressive effects to prevent graft rejection in allogeneic transplants for leukemia,217 its rationale in autologous transplant for lymphoma is mainly for tumor cell kill. The role of TBI in addition to myeloablative doses of chemotherapy in the autologous transplant setting has not been formally tested in a phase III trial. Therefore, the use of TBI in intensive therapy regimens has been largely dictated by the local experience of the transplant center and the availability of TBI. TBI appears to be more commonly used in North America213,218–220 than in Europe.189,221,222 The total dose for TBI is limited to 12 to 14 Gy in 1.5- to 2.0-Gy fractions delivered two or three times a day. The addition of TBI to chemotherapy conditioning undoubtedly contributes to acute morbidity and the risk of post-transplant complications,223,224 unless the dose intensity of chemotherapy is adjusted. Previous IFRT, particularly to the thorax, given just before bone marrow transplantation was a risk factor for increased mortality.213,219,225–227 The European Bone Marrow Transplantation Working Party experience with indolent lymphomas showed no difference in progression-free survival with or without TBI in the conditioning regimen.222 Therefore it remains unclear whether the therapeutic ratio of TBI is favorable enough in the transplant setting to be used routinely outside a trial. Innovative approaches using radioimmunotherapy to more selectively deliver targeted radiation in the salvage setting before bone marrow transplantation are under investigation.228

Management of Primary Extranodal Lymphomas

For a designation of primary extranodal lymphoma, in the context of gastrointestinal lymphoma Dawson and colleagues229 proposed that a patient had to present with main disease manifestation in an extranodal site and only may have had regional lymph node involvement, with no peripheral lymph node involvement and no liver or spleen involvement. Later these criteria were relaxed to allow for contiguous involvement of organs including liver and spleen and allowed for distant nodal disease, providing that the extranodal lesion was the presenting site and constituted the predominant disease bulk.230 Primary extranodal lymphomas account for 25% to 45% of all lymphomas.46,231,232 The most common is skin lymphoma, with the majority of them being of T-cell histology.232 For B-cell histology, the most common are gastric lymphoma, Waldeyer’s ring lymphoma (tonsil lymphoma being most frequent),46 and brain lymphoma. Others sites include intestine, lung, orbital adnexa, bone, extradural regions, thyroid, testis, and other less common sites such as paranasal sinuses, breast, and bladder. Many of these lymphomas have unique clinical characteristics. Because of the propensity of extranodal lymphomas to be truly localized, they are of special importance to the radiation oncologist.

Gastric Lymphoma

MALT Lymphoma

Permanent regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric MALT lymphoma after treatment with antibiotics indicates that eradication of H. pylori is sufficient therapy for the majority of patients with H. pylori–associated MALT lymphoma of the stomach.25,57,123,233 Depending on the strictness of the response criteria, complete response rates of 50% to 95% have been reported. Recommended anti-Helicobacter triple-drug therapy includes a proton pump inhibitor (or ranitidine bismuth citrate), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (or metronidazole).234,235 The expected rates of eradication of Helicobacter are over 90%.26,233 Adjuvant chlorambucil therapy did not confer additional benefit.236 Although eradication of H. pylori may be seen soon after the completion of drug therapy, disappearance of lymphoma usually takes several months, and delays up to 18 months to histologic complete response have been documented. Molecular markers t(11;18)(q21;q21) and trisomy 3 predict for antibiotic resistance.122,233,237,238 The t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation has been found in high frequency in gastric MALT lymphoma not associated with H. pylori.239 The presence of these markers and the lack of response to antibiotic therapy are two main indications to treat with definitive RT. Patients with asymptomatic minimal residual disease can have an indolent course and not require further treatment,25,240 particularly if they are elderly or infirm. The results of treatment with RT are excellent. In a small prospective series Schechter and associates documented a 100% complete response rate after RT to a median dose of 30 Gy (range, 28.5 to 43.5 Gy). At a median follow-up of 27 months, no failures were observed.241 Other investigators45,242 documented similar results. A dose of 30 Gy appears adequate. Another approach to the management of antibiotic-refractory gastric MALT lymphoma involves the use of chlorambucil alone,243 rituximab,244,245 or combination chemotherapy.246 Regardless of the choice of treatment, the disease is generally indolent biologically. Further phase II and phase III clinical trials are required to define the optimal management for this disease.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

In the past, most patients with gastric lymphoma were diagnosed at surgery and treatment for DLBCL included surgical resection with postoperative RT or postoperative chemotherapy. In the past two decades, nonsurgical approaches with primary chemotherapy followed by RT produced similar results.247–252 At the Princess Margaret Hospital, patients with stage IA and IIA gastric lymphoma treated with complete gross surgical resection and low-dose (20 to 25 Gy) postoperative RT had an 86% 10-year relapse-free survival.250 D’Amore reviewed the Danish Lymphoma Study Group experience and found that patients with gastric lymphoma who received RT as part of their therapy had a reduced relative risk of relapse to 0.3.83 Others have shown good results in patients with complete resection of tumor followed by full-course chemotherapy alone.253

The current standard of therapy is stomach preservation with combined CHOP-R chemotherapy and RT. Patients with H. pylori infection should also receive antibiotics to eradicate this infection.254 Chemotherapy alone, with rituximab (without routine RT), is curative in a substantial proportion of patients with DLBCL,254–256 but the data are not mature enough to safely delete RT at this time. Moderate-dose RT (30 to 40 Gy) will produce high local control rates.256 In most instances the RT toxicity can be reduced by using three-dimensional conformal techniques or intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) to minimize the dose to the liver and the kidneys. The planning target volume margin is defined using four-dimensional CT or fluoroscopy to allow for breathing and setup variation.257

Intestinal Lymphoma

Primary small bowel lymphoma is more common than large bowel or rectal lymphoma. Distinct histologic presentations include MALT lymphoma, DLBCL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and α-heavy chain disease (immunoproliferative small intestinal disease [IPSID]). Intestinal lymphoma is commonly diagnosed at laparotomy, and surgical resection is standard. In advanced disease, when resection is not technically feasible, treatment comprises anthracycline-based chemotherapy followed, in some cases, by RT. Indolent intestinal lymphoma may be treated with surgical resection followed by adjuvant whole-abdominal RT (20 to 25 Gy in 1.0- to 1.25-Gy daily fractions). In aggressive histology lymphoma, surgery followed by chemotherapy is recommended. If a short course of chemotherapy is used, whole-abdominal RT is added. In patients in whom complete tumor resection is not feasible, chemotherapy followed by RT is recommended.258,259 In the absence of randomized trials, the optimal treatment strategy is controversial. The outcomes reported in the literature vary depending on the extent of disease and histology. In a large series of intestinal lymphomas, Domizio and coauthors260 documented a 75% 5-year survival for patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas and only a 25% 5-year survival for those with T-cell tumors.

The poor outcome of patients with intestinal T-cell lymphoma has been documented by multiple investigators.40,261,262 Prognostic factors in primary intestinal lymphoma include, besides phenotype, age, performance status, B symptoms, and mesenteric lymph node involvement (stage II disease).40,261,262

α-Heavy chain disease and Mediterranean lymphoma refer to various manifestations of a B-cell lymphoma of MALT type affecting the small intestine.263,264 It is chiefly observed in the Middle East and Africa. Patients present with poor performance status and severe malabsorption and frequently cannot tolerate standard therapy. Several authors have reported that treatment with the tetracycline group of antibiotics265 or H. pylori eradication266 can produce clinical, histologic, and immunologic remissions. Remissions have also been described after chemotherapy.267 Historically, α-heavy chain disease is a highly lethal disease with survival rates as low as 23% at 5 years.268 Patients with resectable stage I and II1 disease have a 5-year survival of 40% to 47% compared with 0% to 25% for unresectable or stage II2 disease. Fortunately, there appears to be a decrease in the incidence of this disease associated with improvements in sanitation and health facilities in some parts of the world.269

Rectal presentations are less common than other sites in the lower intestinal tract. DLBCL is the most common, although other lymphomas also occur.270,271 Treatment usually includes chemotherapy followed by RT (35 Gy in 1.5- to 2.0-Gy daily fractions) for patients presenting with bulky lesions. IFRT alone (30 Gy in 1.5- to 1.75-Gy daily fractions) has been successful in providing long-term disease control for MALT lymphoma of the rectum.45

Waldeyer’s Ring Lymphoma

Combined-modality therapy is the standard approach and results in local control rates in excess of 80% and survival rates of 60% to 75% depending on the bulk and nodal extent of the presenting lesion.46,84,272,273 Location of disease in the tonsil only is a favorable prognostic attribute.273 A prospective randomized trial by Aviles and associates274 demonstrated the superiority of combined-modality therapy in this disease with 5-year failure-free survival rates of 48% for RT alone, 45% for chemotherapy alone, and 83% for combined-modality therapy (p <.001), thus establishing combined-modality therapy as the standard therapeutic approach.

Paranasal Sinuses and Nasal Lymphoma

Paranasal sinus lymphoma includes several distinct diseases. Important differences in clinical features, phenotypic and genotypic characteristics, and prognosis are apparent between disease occurring in Western275,276 and Asian populations.277,278 Common presenting features include painless nasal obstruction, nasal discharge or bleeding, facial swelling, or palatal lesions with dental impacts. Involvement of the orbit can cause epiphora, proptosis, or diplopia. Tumors are most commonly of DLBCL type in North America and Europe. In Asia, a destructive, erosive lesion is a characteristic presentation and T-cell/NK-cell tumors predominate and show the characteristic features of angioinvasion, necrosis, and epitheliotropism. Indolent lymphomas are less common. The nasal type of CD56-positive T-cell/NK-cell lymphoma is a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with Epstein-Barr virus.28,41 T-cell/NK-cell tumors with an identical phenotype and genotype can occur rarely in other extranodal sites, usually in the skin, subcutis, gastrointestinal tract, and testis.28,279 For DLBCL, the current practice of combined-modality therapy yields overall 5-year survival rates of 60% to 75%.276,277,280 In T-cell/NK-cell disease, the Asian experience with stage I and II presentations is disappointing, with a response rate to doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy of less than 50% and 5-year survival of 30% to 70%.278,279,281–283 The early use of RT to a higher dose of 45 to 50 Gy appears to be important for optimal local control.278,279,284,285 For patients who responded favorably to initial treatment, the use of consolidation therapy with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation appears to result in prolonged remissions.42

Salivary Gland Lymphomas

The parotid gland is the most common presenting site. An increased risk is seen in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome.286,287 Myoepithelial sialadenitis, which is characteristic of Sjögren’s syndrome, is a part of the spectrum of salivary gland MALT lymphoma. These lymphomas generally follow an indolent course and tend to remain localized for prolonged periods of time. RT offers excellent local control. Aviles and associates288 showed a complete remission rate of 100% and 5-year survival of 90% and no advantage for chemotherapy. Equally good results with local therapy were obtained by other investigators.45,289 Therefore there is no role for chemotherapy in the management of indolent tumors, although combined-modality therapy using an anthracycline-based regimen is standard for transformed aggressive histology lesions.

Thyroid Lymphomas

Thyroid lymphomas occur more often in women than men, and the median age at presentation is older than 60 years. Patients often present with a rapidly enlarging, bulky neck mass causing local aerodigestive obstructive symptoms. Primary thyroid lymphoma occurs most frequently in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.290,291 MALT lymphomas are common and have a better prognosis than non-MALT tumors.292 Surgery is a diagnostic procedure, and thyroidectomy is not indicated for clinically evident lymphoma diagnosed by fine-needle or core biopsy.293 Combined-modality therapy has become the standard treatment approach for DLBCL. With chemotherapy and locoregional RT (35 to 40 Gy), local control is achieved in the majority of patients294 and survival and relapse-free survival should exceed 75%.295–297 For localized MALT or follicular lymphomas, RT alone is appropriate therapy with a local control rate of over 95% expected.45 Adequately treated MALT lymphoma of the thyroid rarely relapses systemically.45,298

Orbital Lymphomas

Orbital lymphomas are commonly seen in elderly patients, with a median age in the sixth decade. These tumors may arise in superficial tissues, including the conjunctiva and eyelids, or in deep tissues, including the lacrimal gland and retrobulbar tissues.299 MALT lymphoma is most often seen in the conjunctiva, whereas retro-orbital presentations are associated with DLBCL histology300 but are less common.301 Treatment is directed to cure, while preserving vision and the integrity of the orbit. Orbital lesions are easily controlled with low doses of RT (25 to 30 Gy in 10 to 20 daily fractions), with a local control rate of 95% or more.45,125,302–305 Higher doses are not required, and their use results in increased acute and long-term morbidity. The whole orbit should be treated.306 Conjunctival MALT lymphoma treated with surgical excision only has been occasionally observed to regress spontaneously.307 For less common, diffuse large cell lymphoma, chemotherapy followed by RT to a dose of 30 Gy in 1.5-Gy daily fractions is recommended. The overall actuarial 10-year survival rates are 75% to 80% and are in part due to a predominance of indolent histology. The risk of locoregional failure is extremely low. Contralateral orbit involvement is common either synchronously or metachronously. Distant failure rates vary from 20% to 50%, but, as in other cases of indolent lymphoma, prolonged survival is observed.45,299,308 In patients with bulky tumors in which the cornea cannot be protected, RT alone may result in severe radiation complications. In such cases, chemotherapy alone or combined-modality therapy is preferable.

Testicular Lymphomas

In contrast to germ cell tumors, primary testicular lymphoma affects mostly men older than the age of 50. Staging assessment is focused on identification of para-aortic lymph node involvement and distant spread, particularly to the CNS. Initial therapy invariably involves orchiectomy. Almost all testicular lymphomas are of the DLBCL type. Reported overall 5-year survival rates range from 16% to 65% with median survivals of 12 to 24 months.186,309–311 Distant failures were commonly observed. In the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) study of 373 patients, 57% had stage I and 21% had stage II disease.186 Median PFS was 4 years. High risk of CNS relapse was observed with an actuarial risk of 34% at 10 years.186 CNS relapse has been documented despite the use of chemotherapy.312,313 Other sites of relapse involve extranodal organs, including skin, pleura, Waldeyer’s ring, lung, liver, spleen, bone, and bone marrow. Failure in the contralateral testis is well documented and occurs in 15% of patients at 3 years, rising to an actuarial risk of 42% at 15 years.186 Scrotal irradiation with moderate doses (25 to 30 Gy in 10 to 15 daily fractions) reduces this risk to less than 10%.186 Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy improves survival of patients with localized testicular lymphoma.186 A clear pattern of failure in the CNS warrants a recommendation for routine CNS prophylaxis with intrathecal chemotherapy,311 and the IELSG data suggest that a combination of the systemic and intrathecal therapy with scrotal RT was associated with an improved outcome.186

Bladder Lymphomas

Primary NHL of the urinary bladder is rare. Published case reports indicate that primary lymphoma of the bladder occurs mostly in the sixth and seventh decades of life and is more common in women. MALT lymphomas have been observed, and the prognosis is favorable.45,314 Large cell lymphomas have also been described.315 The prognosis is related to histologic type and extent of tumor. As in other extranodal lymphomas, indolent lymphomas are managed with RT alone, but aggressive lymphomas are treated with combined-modality therapy. Several reports suggest that primary lymphoma of the bladder is associated with a favorable prognosis.314,316,317 Long-term survival historically has been observed in 40% to 50% of patients.

Female Genital Tract Lymphomas

Ovarian Lymphomas

Lymphoma of the ovary is rare as a primary presentation, although Burkitt’s lymphoma has a predilection to involve the ovary.318,319 The disease is commonly bilateral and often bulky. A 2-year and 5-year OS of 42% and 24% have been cited.320 Because lymphomas of the ovary are most commonly of aggressive histology, the initial treatment approach should include combined-modality therapy.321 Burkitt’s lymphoma is managed primarily with chemotherapy alone.319

Lymphoma of the Uterus, Cervix Uteri, and Vagina

The standard therapy for patients with stage IE lesions has usually comprised RT with or without surgery. However, there is no evidence that radical resection is necessary. RT alone for localized indolent histology tumors offers a very high probability of local control, and combined-modality therapy is appropriate for aggressive histology tumors.322–324 Given the impact of RT on ovarian function in those in the reproductive age range, the use of chemotherapy alone has been recommended with some clinical justification. A 5-year OS of 73% is quoted by Harris and Scully,325 comprising an 89% 5-year survival for patients with stage IE disease.

Breast Lymphoma

Breast lymphoma affecting young women tends to be associated with pregnancy and lactation and is a lymphoma of aggressive histology commonly presenting as bilateral disease diffusely involving both breasts. In contrast, the disease affecting older women tends to present as discrete masses that commonly are unilateral. Reports in the literature suggest synchronous bilateral involvement in up to 13% of cases and metachronous contralateral involvement in 7% of cases. The most common histologic type is DLBCL.326 Lymphomas of indolent histology are less common and, if observed, usually consist of secondary involvement from systemic disease.327,328 MALT lymphoma affecting the breast is rare but has been reported.327,329 Mastectomy is not recommended, and the breast is preserved in the majority of cases. RT results in excellent local control, especially in patients presenting without bulky disease or those with indolent histology. The overall survival of patients treated with local treatment methods ranges from 40% to 66% at 5 to 10 years.326,327,330 The local control rates in patients treated with RT alone range from 75% to 84%.326,327,331,332 Isolated CNS relapses have been reported.326 Similarly, late failure in the contralateral breast may occur after therapy for unilateral primary breast lymphoma.326 Combined-modality therapy is recommended for aggressive lymphomas,326,333 whereas patients with indolent lymphoma can be successfully treated with RT alone.327 CNS prophylaxis with intrathecal chemotherapy should be given to all patients with very aggressive histology, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma.

Bone Lymphoma

With RT alone, 5- and 10-year OS of 58% and 53% have been reported for solitary bone lesions. Key issues relating to local control are the intramedullary and soft tissue extent of disease in relation to RT volume. MRI is particularly important in revealing extension of disease in the bone and soft tissues. Treatment approaches using RT have given high levels of local control (85%) but unacceptable rates of local or marginal failure (20%), probably related to underestimation of tumor extent and bulk, and systemic failure rates approaching 50% were reported. Therefore, patients with localized lymphoma of bone should be treated with combined-modality therapy comprising initial anthracycline-based chemotherapy and IFRT.334 There is no indication for CNS prophylaxis. With chemotherapy and RT the OS and relapse-free rates should exceed 70% to 80% at 5 years.334,335–339

Lung Lymphoma