Chapter 5 Nomenclature, representation of chemical structures and basic terminology

The Functional Groups

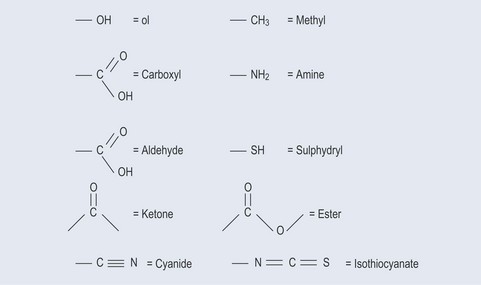

Figure 5.1 demonstrates the different types of functional groups you are likely to see. Each of these functional groups has a characteristic chemical reaction. It is not necessary for you to know these in detail, but it is helpful to appreciate them with regards to a particular pharmacological activity.

Shorthand can sometimes be used for the chemical formulae of short functional groups such as:

There can be quite a variety of these; with a little deduction they are fairly obvious.

Many of these functional groups will be attached to a hydrocarbon backbone, which is composed of carbon and hydrogen atoms (see Chapter 4 ‘Bonds: continued’, p. 24).

Naming Compounds with a Hydrocarbon Backbone

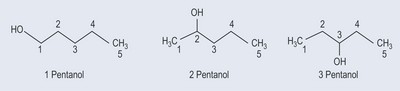

Figure 5.2 shows how this applies in a simple alcohol. The same principle applies to other functional groups.

Naming Aromatic Compounds

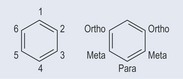

The left-hand side of Figure 5.3 shows the new IUPAC style of nomenclature; the right-hand side shows the old style of nomenclature, which can still be seen in some literature. A benzene ring is an example of a conjugated compound where double bonds alternate with single bonds.

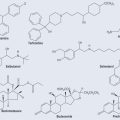

More Complex Structures of Substances Encountered in Pharmacology

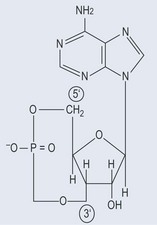

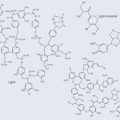

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is usually just known as cAMP (Figure 5.4), but you might also see it as 3′-5′ cAMP, which is technically more precise. This notation indicates that a phosphate is linked to both the 3′ and 5′ hydroxyl groups of an adenosine molecule to form a cyclical structure.

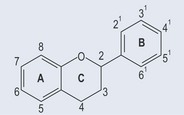

When several rings are involved in the structure, as can be seen in compounds such as flavonoids, it becomes necessary to differentiate the rings (Figure 5.5).

Naming Sugars

Sugars are a particular area where nomenclature is used extensively to cover all aspects of the sugar structure as there are so many variations. A basic introduction to this is given in Chapter 9 ‘Carbohydrates’ (p. 66).

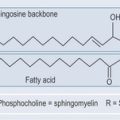

Further Shorthand

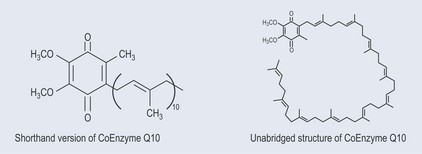

When a very long chain of similar molecules is present in a chemical, a shorthand is used to simplify the presentation of the structure. Take, for example, coenzyme Q10 (Figure 5.6). The unabridged structure on the right is complicated to draw and requires careful counting to calculate the number of carbon atoms in the chain. However, in the abbreviated form on the left it is easy to appreciate the size of the molecule. This shorthand identified the recurring unit – in this case CH2–CH=CH2 – which occurs ten times.

R Groups

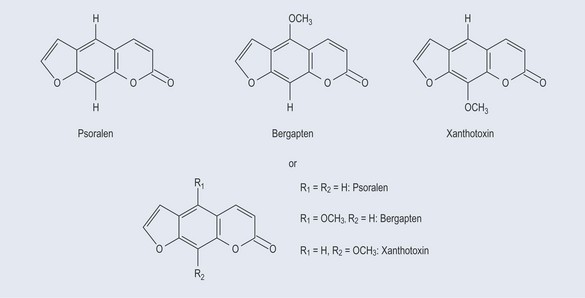

Figure 5.7 demonstrates the variations of the coumarins (see Chapter 21 ‘Phenols’, p. 156), psoralen, bergapten and xanthotoxin, in which R is the side-chain group.

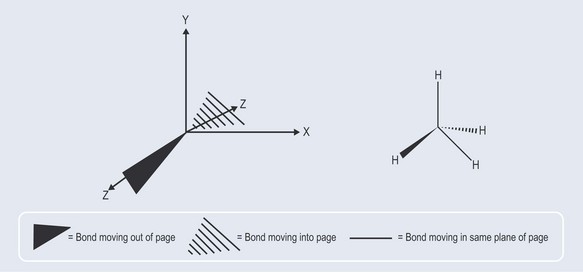

Two-Dimensional Representations of Three Dimensional Shapes (Figure 5.8)

As seen in Chapter 3, chemical structure can be represented in several ways, particularly if it is necessary to represent a three-dimensional structure. There are other devices for indicating three-dimensional structures, many of which are self-evident (Figure 5.8).

Some General Terminology

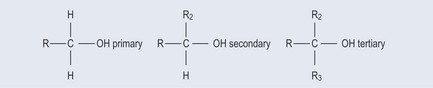

Primary, Secondary, Tertiary

Although you are most likely to come across the terms ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘tertiary’ when working with alcohols and bases, they can be used for other compounds (however, amino acid configuration is slightly different; see Chapter 11 ‘Amino acids and proteins’, p. 83). The definition depends on the number of hydrogen atoms attached to the carbon atom bearing the group (Figure 5.9).

Naming Orthodox Medication

Modern medication tends to be known by its brand name, which is likely to be different in each country. For example, the chemical name for the drug Prozac is fluoxetine, but ‘Prozac’ – the brand name – is the name most commonly used. Looking at the chemical structure will leave you in no doubt as to whether you are looking at the same chemical compound.

If you are looking at medication in an international context, it is best to search by the chemical name, although several online search mechanisms will look specifically for medication (see Chapter 42 ‘Information gathering’, p. 342).