Nissen Fundoplication

Surgical Principles

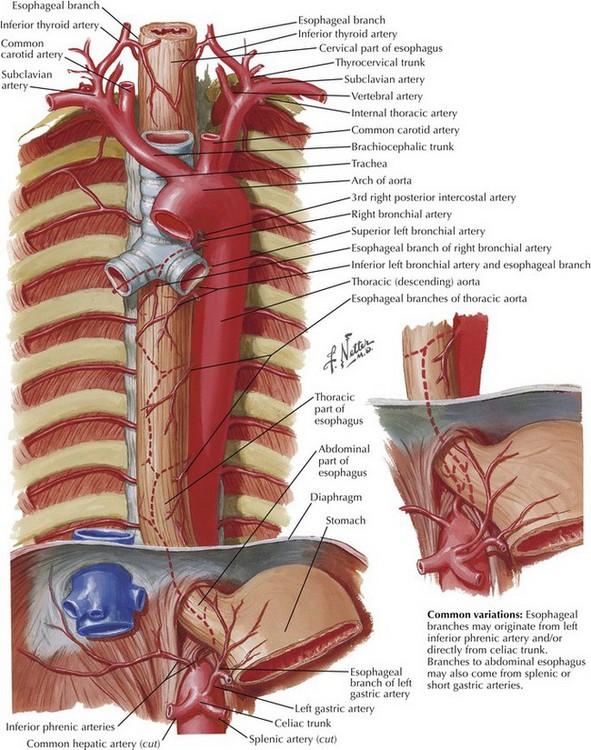

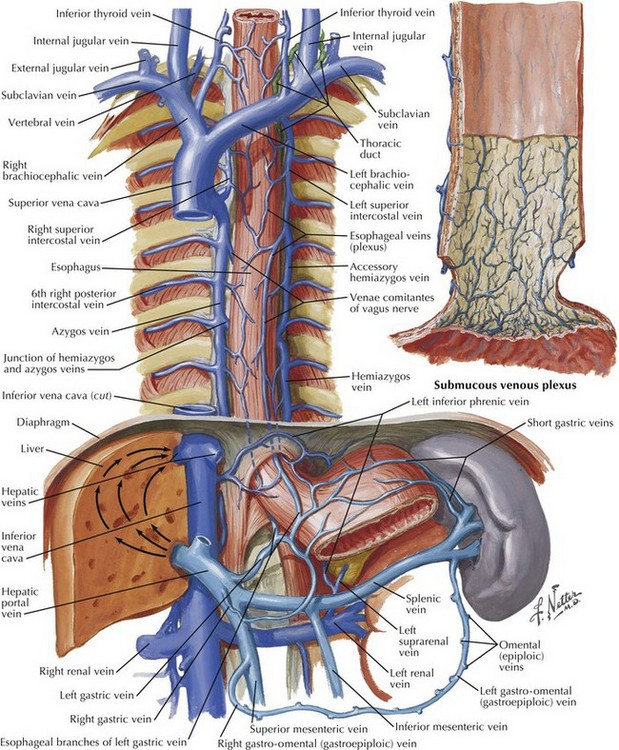

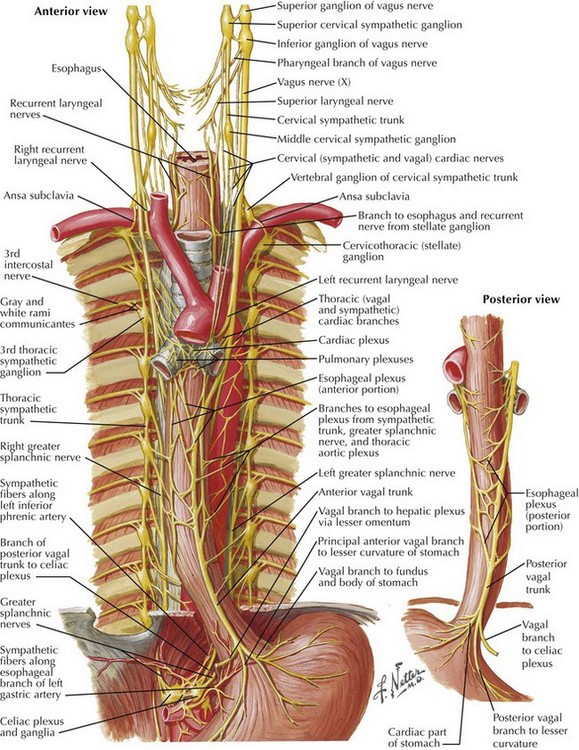

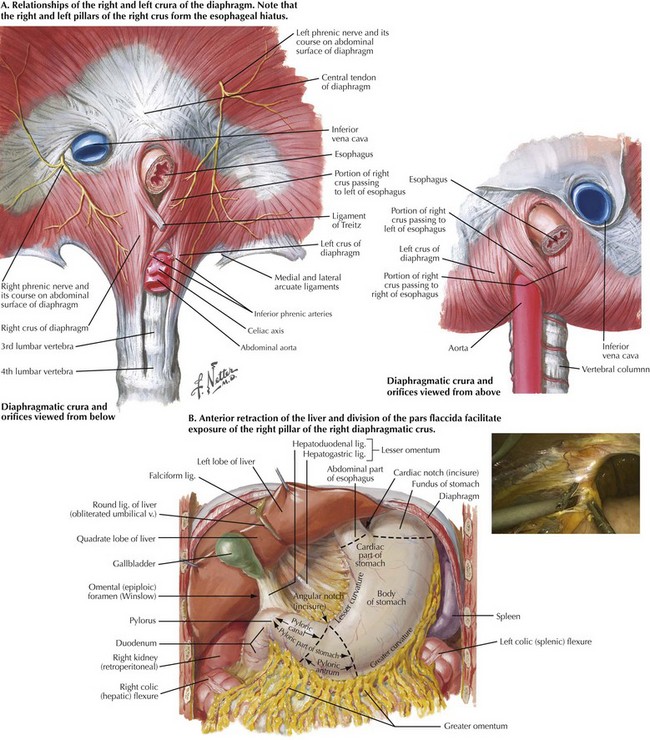

The goals of successful surgical management of GERD are to restore the intraabdominal esophagus, repair the diaphragmatic crura, and reestablish a competent lower esophageal sphincter. A thorough understanding of hiatal anatomy, upper abdominal organ relationships, and mediastinal structures is critical to safe and effective operations for GERD (Figs. 6-1 to 6-3). Restoration of the lower esophageal sphincter is usually accomplished with a “floppy” 360-degree (Nissen) fundoplication formed around the distal esophagus.

Preoperative Studies

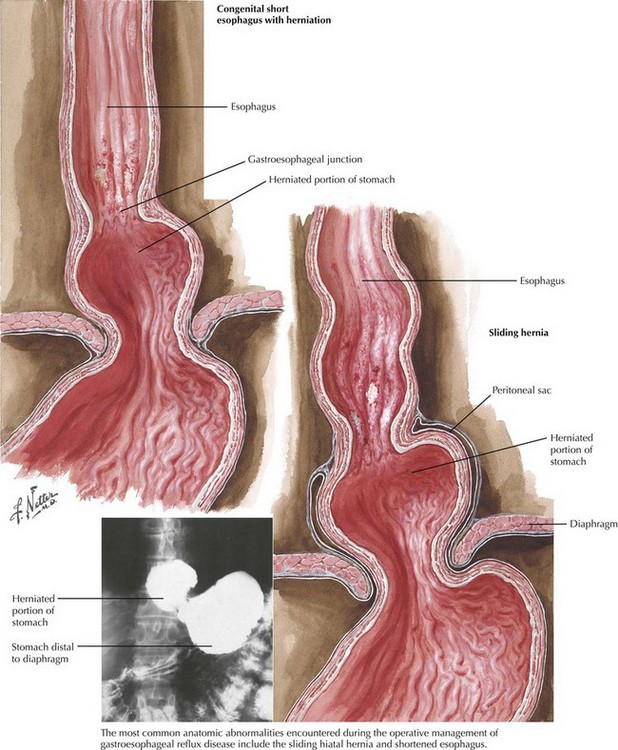

Upper endoscopy can reveal intraluminal pathology that can alter surgical decision making and can help ascertain anatomic changes that would impact the operation for GERD. The most common anatomic abnormality seen in this setting is the sliding, type I hiatal hernia (Fig. 6-4). Upper endoscopy can also reveal a shortened esophagus. The upper GI series also helps define anatomic abnormalities and is useful when more complex hiatal hernias are noted (types II-IV). Testing for acid exposure, nonacid reflux, and assessment of esophageal motility are also important nonimaging modalities that help in preoperative decision making.

Anatomy for Esophageal Mobilization

Diaphragmatic Crura (Superior and Inferior Views)

In most patients the fibers of the right crus of the diaphragm encircle the esophagus, making the right and left pillars of the right crus the pertinent structures of the esophageal hiatus (Fig. 6-5, A). Abdominal exposure of the right crus is usually obtained by retraction of the left lobe of the liver anteriorly and by incision of the filmy pars flaccida. The right pillar is usually readily identified and bluntly separated from the esophagus (Fig. 6-5, B). If a sizable hiatal hernia is encountered, the plane between the hernia sac and mediastinal structures is developed while preserving healthy endoabdominal fascia overlying the pillars of the crus.

Phrenoesophageal Ligament

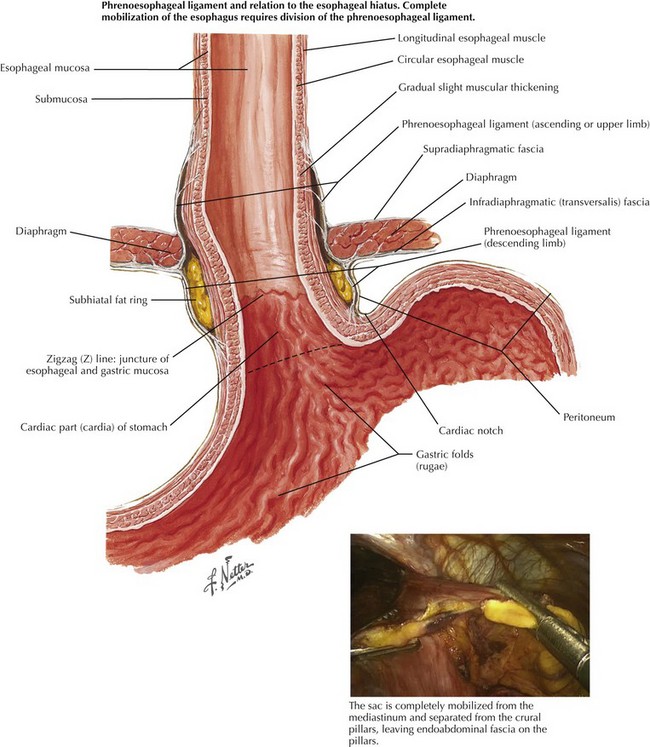

Division of the phrenoesophageal ligament is required to free the esophagus from its immediate surrounding attachments. Figure 6-6 shows the relationship of the phrenoesophageal ligament to the esophageal hiatus. Division of this ligament for more complete esophageal exposure often requires excision of the fatty tissue anterior to the esophagus. Care is taken to preserve the anterior vagus nerve.

Anatomy for Gastric Mobilization

Short Gastric Vessels

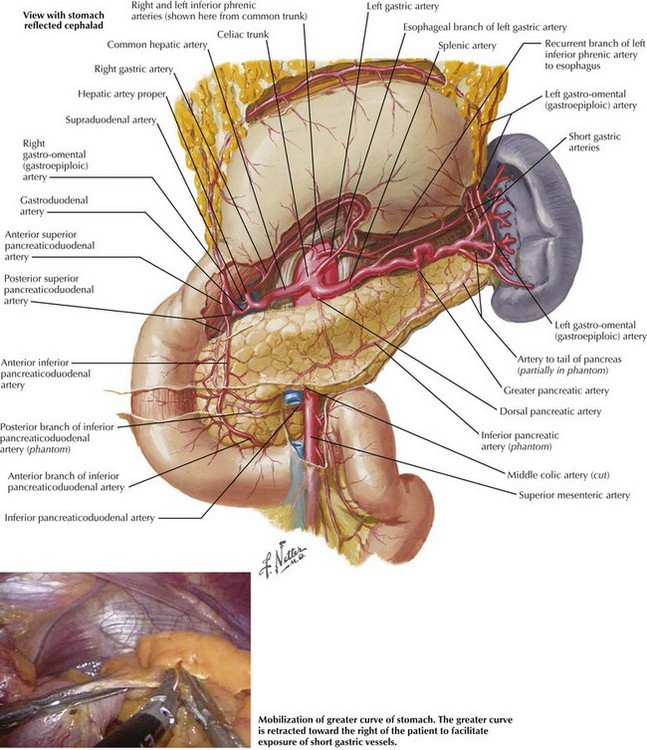

Dissection commences at the level of the inferior pole of the spleen, about 1 cm from the greater curve. At this point the short gastric vessels are divided using an appropriate energy source (ultrasonic shears or bipolar electrosurgery), and the lesser sac is entered (Fig. 6-7). As the short gastric vessels are divided cephalad, care is taken to avoid splenic or gastric injury while ensuring hemostasis. As the left pillar is approached, it is critical to ensure hemostatic transection of the short gastric vessels because hemorrhage in this area can be difficult to control. Posterior gastric attachments to the pancreas are also divided to ensure adequate gastric mobilization.

Anatomy for Crural Closure and 360-Degree Fundoplication

Crural Closure

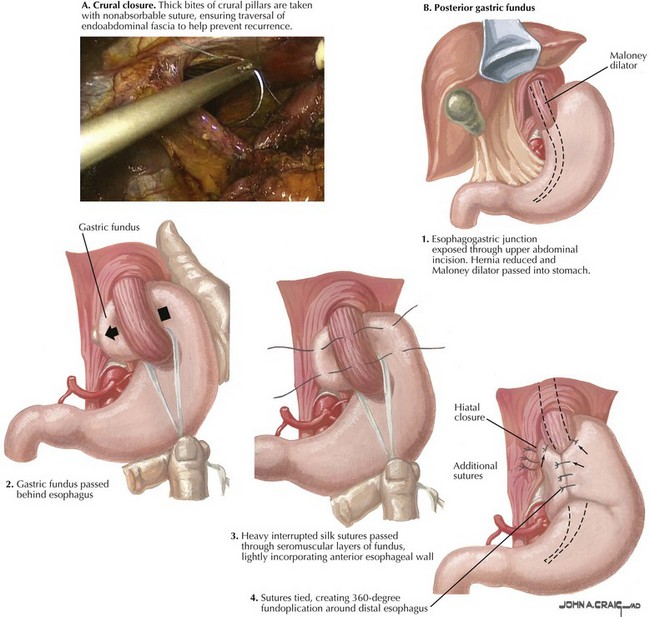

Thick bites of crura are taken with nonabsorbable suture, ensuring healthy bites of endoabdominal fascia as well as muscle (Fig. 6-8, A). Pledgets can be used to buttress tenuous tissue. Care is taken not to injure the aorta posteriorly or the inferior vena cava to the right of the hiatus. An adequate opening is left to allow passage of a 58- to 60-Fr bougie to prevent dysphagia.

Identification of Posterior Gastric Fundus

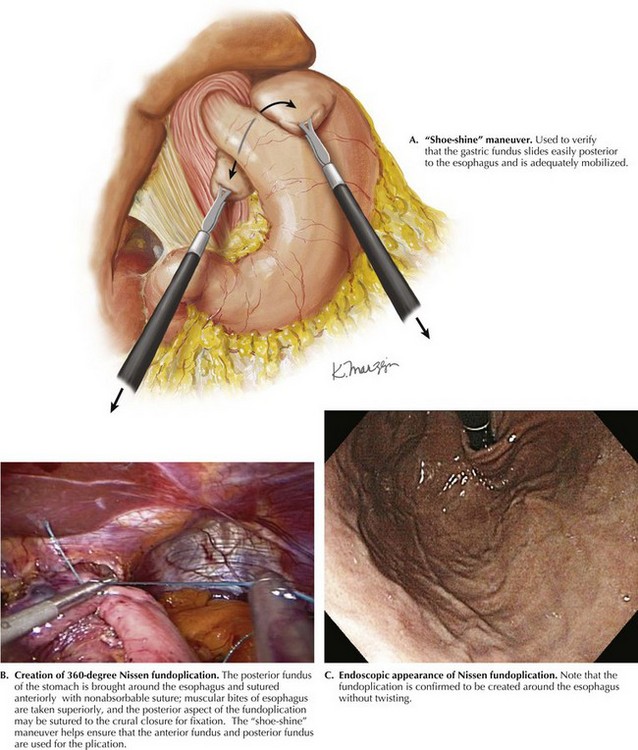

The mobilized greater curvature of the stomach is identified and followed cephalad until the posterior gastric fundus is visualized. This is “fed” from left to right through the retroesophageal space while maintaining anterior traction on the esophagus (Fig. 6-8, B). Care is taken to ensure that the posterior fundus is passed behind the esophagus, and that the fundus is not simply passed behind the stomach itself. This can be facilitated by performing the “shoe-shine” maneuver, which helps to confirm the position of the anterior and posterior fundus for plication (Fig. 6-9, A). Adequate mobilization is ensured such that the posterior fundus does not retract readily back through the retroesophageal space.

Fundoplication Created around Esophagus

Nonabsorbable mural sutures are placed on each side of the fundoplication, taking mural esophageal bites superiorly to create a 2-cm fundoplication (Fig. 6-9, B). These sutures are placed such that the entire wrap is performed around the esophagus. A floppy fundoplication is preferred; careful passage of a bougie can help assess the “floppiness” of the fundoplication. Upper endoscopic evaluation is then performed to confirm adequate formation and position of the fundoplication (Fig. 6-9, C).

DeMeester, TR, Bonavina, L, Albertucci, M. Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: evaluation of primary repair in 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 1986;204(1):9–20.

Nissen, R. [Hiatus hernia and its surgical indication]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1955;80(14):467–469.