CHAPTER 4 Nissen fundoplication

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

The antireflux barrier

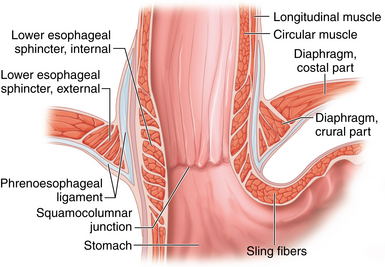

♦ The antireflux barrier of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction depends on proper anatomic alignment of the distal esophagus, proximal stomach, and the diaphragm. The intrinsic muscle fibers of the distal esophagus coordinate with the sling fibers of the cardia and muscle fibers of the diaphragm to prevent reflux of gastric acid into the distal esophagus (Figure 4-1).

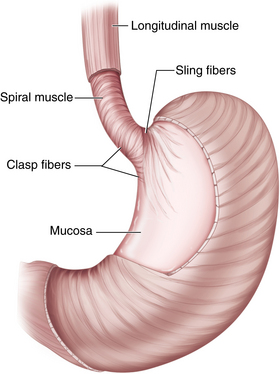

♦ Tonic contraction of the sling and claps fibers of the GE junction works to maintain the acute angle of His. This contributes to the gastroesophageal flap valve mechanism, which further prevents gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) (Figure 4-2).

♦ Restoration of the normal anatomic position of the GE junction and re-creation of the flap valve mechanism through fundoplication are critical elements for a successful antireflux procedure.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ In patients with objective evidence of gastroesophageal reflux, the indications for surgery include the following:

Persistent or breakthrough symptoms despite the use of maximal medical therapy (this typically includes patients with volume reflux, or regurgitation)

Persistent or breakthrough symptoms despite the use of maximal medical therapy (this typically includes patients with volume reflux, or regurgitation) Complications of reflux disease, including Barrett’s esophagus, refractory esophagitis, and esophageal strictures

Complications of reflux disease, including Barrett’s esophagus, refractory esophagitis, and esophageal strictures Supralaryngeal symptoms of reflux disease, including chronic cough, aspiration, asthma, or hoarseness

Supralaryngeal symptoms of reflux disease, including chronic cough, aspiration, asthma, or hoarseness Prior to surgical intervention, all patients require upper endoscopy. This provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent of esophagitis and rule out Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal malignancy.

Prior to surgical intervention, all patients require upper endoscopy. This provides an opportunity to evaluate the extent of esophagitis and rule out Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal malignancy. Esophageal manometry is an essential study prior to antireflux surgery to rule out the presence of a severe motility disorder, such as achalasia. This is an important issue, because many of the symptoms of achalasia (regurgitation, heartburn) can mimic those of GERD, whereas the treatment is obviously very different.

Esophageal manometry is an essential study prior to antireflux surgery to rule out the presence of a severe motility disorder, such as achalasia. This is an important issue, because many of the symptoms of achalasia (regurgitation, heartburn) can mimic those of GERD, whereas the treatment is obviously very different. Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH studies should be used selectively. Patients with classic reflux symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) and esophagitis on endoscopy do not require any further evidence of GERD. However, patients with nonerosive disease and those with primarily supralaryngeal symptoms should undergo a 24-hour pH study to document the presence of abnormal reflux.

Ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH studies should be used selectively. Patients with classic reflux symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) and esophagitis on endoscopy do not require any further evidence of GERD. However, patients with nonerosive disease and those with primarily supralaryngeal symptoms should undergo a 24-hour pH study to document the presence of abnormal reflux. Upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopic imaging is useful for defining gastroesophageal anatomy in patients who present with dysphagia or who have previously diagnosed large hiatal hernias.

Upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopic imaging is useful for defining gastroesophageal anatomy in patients who present with dysphagia or who have previously diagnosed large hiatal hernias.Equipment and instrumentation

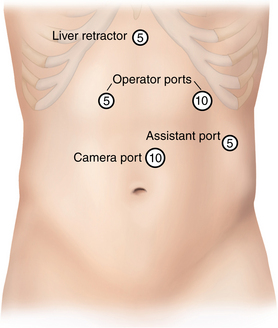

♦ We perform the procedure using five ports—three 5-mm ports and two 10-mm ports—as well as a 10-mm, 30-degree angled laparoscope.

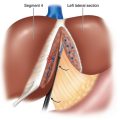

♦ A Nathanson retractor is used to elevate the left lateral segment of the liver.

♦ Handheld laparoscopic instruments include atraumatic bowel graspers, scissors, and needle drivers.

♦ We prefer the 5-mm ultrasonic dissector for dissection and hemostasis.

♦ A ¼-inch, 5-cm long Penrose drain is used to facilitate retraction of the esophagus. The ends of the Penrose drain are anchored together anterior to the esophagus using a 0 chromic or Vicryl Endoloop (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts).

♦ Permanent suture (0 silk or Ethibond, Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) with felt pledgets is used to close the crural defect. The fundoplication is performed with the same suture but without pledgets.

♦ For large crural defects (>4 cm), we use synthetic or biologic mesh to buttress the crural closure.

Anesthesia

♦ Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism includes the use of sequential lower extremity compression devices and subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin.

♦ Perioperative antibiotics, typically a first-generation cephalosporin, are recommended.

♦ Following induction of general anesthesia, an orogastric tube and Foley catheter are inserted. They can be removed at the conclusion of the procedure.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ Pneumoperitoneum is established with a Veress needle at the umbilicus or below the left costal margin.

♦ A 10-mm camera port is placed to the left of midline and 15 cm below the junction of the right and left costal margins. A 5-mm port is placed in the subxiphoid position. This port is then removed and replaced with the Nathanson liver retractor, which is used to elevate the left lateral segment of the liver to expose the proximal stomach and esophageal hiatus. A 10-mm port in the left upper quadrant and a 5-mm port in the right upper quadrant serve as the surgeon’s two working ports, and a 5-mm assistant’s port is placed laterally in the left upper quadrant (Figure 4-3).

♦ Following port placement, the operating table is placed into the reverse Trendelenburg position. The surgeon operates from between the legs, while the assistant stands on the patient’s left side. Monitors are placed at the head of the table at eye level.

♦ Use of an angled 30-degree laparoscope facilitates the dissection.

Hiatal dissection

♦ When present, a hiatal hernia should be reduced prior to starting the dissection in order to reduce the risk of injury to lesser curvature vessels.

♦ Dissection begins by opening the gastrohepatic ligament through its pars flaccida portion, using an ultrasonic dissector. The lesser omentum is incised superiorly to expose the right crus of the diaphragm.

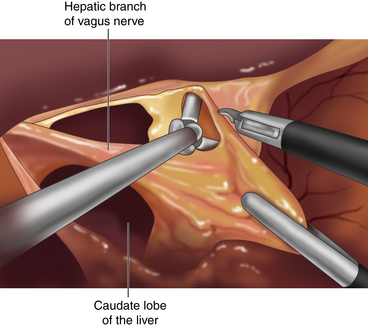

♦ The hepatic branch of the vagus nerve, which runs through the gastrohepatic omentum, is preserved whenever possible to reduce the risk for gallstone formation.

♦ Up to 12% of patients will have an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery that accompanies the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve within the lesser omentum. Injury to this vessel should be avoided. If necessary for exposure, however, the vessel should be divided between hemoclips.

♦ The phrenoesophageal ligament anterior to the esophagus is divided with the ultrasonic dissector or hook electrocautery. It is important to open only the superficial peritoneal layers in order to avoid injury to the underlying esophagus and anterior vagus nerve (Figure 4-4).

♦ Retraction of the stomach to the patient’s right side will facilitate exposure of the left crus. Clearance of the left crus is accomplished by dividing the peritoneal attachments between the cardia and diaphragm at the angle of His.

♦ With the stomach retracted to the patient’s left side, the retroesophageal dissection is begun. The peritoneum anterior to the right crus is divided, and blunt dissection is used to develop a plane between the esophagus and the right crus (Figure 4-4). This dissection proceeds inferiorly toward the decussation of the right and left crura.

♦ Blunt dissection continues posterior to the esophagus to develop the retroesophageal window. The left crus is then identified through the window under the right side of the stomach. Blunt dissection is used to divide attachments between the left crus and the cardia of the stomach.

♦ The posterior vagus nerve must be identified and kept up with the esophagus during this dissection. Unlike the anterior vagus, the posterior vagus nerve often separates from the esophagus as it passes through the hiatus, making it susceptible to injury during the retroesophageal dissection.

Mobilization of the gastric fundus

♦ Complete mobilization of the fundus reduces torque on the fundoplication and may decrease the risk of postoperative dysphagia.

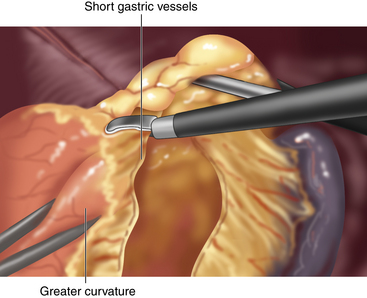

♦ Mobilization of the fundus is accomplished through division of the short gastric vessels. These are divided using the ultrasonic dissector, beginning at the level of the inferior pole of the spleen and ending at the left crus (Figure 4-5).

♦ The assistant facilitates exposure of the short gastric vessels initially by retracting the omentum to the patient’s left, while the surgeon retracts the stomach down and to the right. However, exposure of the proximal short gastric vessels is best achieved by having the assistant retract the posterior aspect of the greater curvature toward the right side.

♦ Once the short gastric vessels have been divided, the remainder of the retroesophageal dissection is completed from the left side. A Penrose drain is then placed behind the esophagus and its two ends are secured anteriorly with clips or a looped suture. The Penrose drain facilitates esophageal retraction during the subsequent mediastinal dissection and crural closure.

Mediastinal dissection

♦ The aim of the mediastinal dissection is to mobilize the esophagus circumferentially until at least 2.5 cm to 3 cm of distal esophagus remains within the abdomen without having to apply any traction on the Penrose drain.

♦ This task is accomplished primarily through blunt dissection and is facilitated by dynamic retraction on the Penrose drain by the assistant. Larger feeding vessels to the esophagus should be divided with the ultrasonic dissector, but care must be taken to avoid injury to the esophagus. Mediastinal bleeding is usually easily controlled by compression with a gauze sponge inserted through a 10-mm port.

♦ The anterior and posterior vagus nerves should be identified and preserved from injury throughout this dissection.

Crural closure

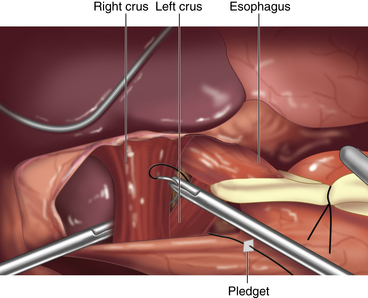

♦ The crural defect is closed using interrupted, nonabsorbable sutures and using either an intracorporeal or extracorporeal knot-tying technique (Figure 4-6).

♦ We use small pledgets on either side of the closure to prevent tearing through the muscle. Pledgets must be seated along the lateral aspect of the crura to prevent contact with the esophagus, as there is a risk for erosion.

♦ The crura should be closed loosely around the esophagus so as to avoid dysphagia.

Fundoplication

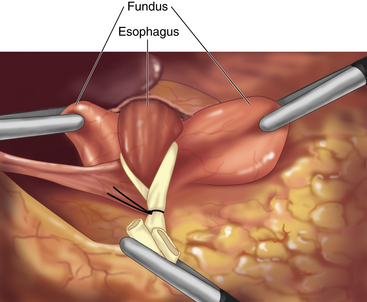

♦ The fundus of the stomach is pulled behind the esophagus. A “shoeshine maneuver” is performed by sliding the fundus back and forth behind the esophagus, and this ensures that the fundus has been adequately mobilized. When properly positioned, the stumps of the short gastric vessels on the fundus should line up to the right of the esophagus (Figure 4-7).

♦ The fundoplication is performed over a 56 French to 60 French esophageal dilator in order to ensure a “floppy” wrap, which helps minimize the risk for dysphagia. Once complete, the surgeon should be able to pass a grasper between the wrap and the esophagus easily.

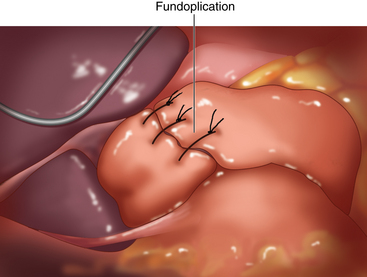

♦ The fundoplication is accomplished using three interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. Each suture incorporates stomach on either side of the esophagus, as well as a bite of the esophagus itself. When taking the esophageal bite, it is important to avoid the anterior vagus nerve. Anchoring the wrap to the esophagus helps prevent slippage of the wrap, which is an important cause for failure of the operation.

♦ The fundoplication sutures are placed 1 cm apart, with the superior suture seated 2 cm above the GE junction and the inferior suture placed at the GE junction. The final wrap, then, is 2 cm in length (Figure 4-8).

Step 4. Postoperative care

Inpatient management

♦ The Foley catheter is removed at the end of the procedure.

♦ Patients are started on an aggressive antiemetic regimen in order to avoid retching, which can disrupt the crural repair and fundoplication.

♦ A liquid diet is started the night of the operation. The patient is advanced to a mechanical soft diet on the first postoperative day and discharged once he or she can tolerate the diet.

Postdischarge management

♦ Patients remain on a soft diet for 3 to 4 weeks and then advance to a regular diet as tolerated.

♦ For the first 4 to 6 weeks after surgery, patients are counseled to avoid raw vegetables, tough meats, breads, and cakes.

♦ Patients who develop bloating should be counseled to eat smaller meals more frequently.

♦ For patients with dysphagia that fails to resolve by 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, endoscopic dilation should be considered.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ The key to success in antireflux surgery is patient selection. Operative candidates should have symptoms clearly attributable to reflux, as well as objective evidence of GERD.

♦ Upper endoscopy and esophageal manometry are essential studies prior to any antireflux operation, whereas 24-hour esophageal pH studies may be performed selectively.

♦ Full mobilization of the fundus is an important step to reduce the incidence of postoperative dysphagia.

♦ Mediastinal dissection should continue until a minimum of 2.5 cm to 3 cm of distal esophagus has been reduced into the abdomen.

♦ The fundoplication should be 2 cm in length and performed over a 56 French to 60 French dilator.

♦ A replaced or accessory left hepatic artery is present in up to 12% of patients and can be injured during dissection of the gastrohepatic ligament.

♦ The anterior and posterior vagus nerves must be identified and preserved from injury throughout the dissection to avoid the risk of gastroparesis.

♦ Energy use near the esophagus, particularly during the mediastinal dissection, is a potential source of unrecognized esophageal injury and should be kept to a minimum.

♦ The proximal short gastric vessels tear easily and should not be put under tension during mobilization of the fundus.

Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(3):292-300.

Fein M, Ritter MP, DeMeester TR, et al. Role of the lower esophageal sphincter and hiatal hernia in the pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3(4):405-410.

Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Waring JP. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The impact of operative technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224(1):51-57.

Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, et al. A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 1996;223(6):673-685.

Jobe BA, Kahrilas PJ, Vernon AH, et al. Endoscopic appraisal of the gastroesophageal valve after antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(2):233-243.

Mittal RK, Balaban DH. The esophagogastric junction. NEJM. 1997;336(13):924-932.