Nipple discharge and the role of ductoscopy in breast diseases

Introduction

After breast lumps and mastalgia, spontaneous nipple discharge forms the next most common symptom, comprising 3–8% of referrals to symptomatic breast clinics.1,2 The majority of nipple discharge is benign, with up to 20% being associated with an underlying malignancy.3 Conventional methods of investigating nipple discharge include mammography, ultrasound and smear cytology, each of which have recognised limitations. Standard operations such as microdochectomy and major duct excision are undirected procedures that carry a risk of leaving undiagnosed pathology in the breast.

Causes of nipple discharge

The causes of nipple discharge are wide ranging. The majority of discharge is physiological, hormone related or results from benign breast change. A recent meta-analysis that included over 3000 women with nipple discharge demonstrated an overall incidence of underlying breast malignancy of 18.7%,3 which is higher than the figure reported in many individual series.

The most common physiological nipple discharge is lactation. Ongoing milky discharge may occur up to 2 years following a pregnancy and is a normal phenomenon. Galactorrhoea can also result from prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas, medication that influences the oestrogen, progesterone or prolactin pathways, hypothyroidism and recreational drugs such as marijuana. Commonly prescribed medical drugs that may cause nipple discharge are summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1

Common drugs that mimic galactorrhea and the likely underlying mechanisms of action

| Mechanism of action | Medication |

| Dopamine receptor blockade | Antidepressants: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline) Tricyclic antidepressants Antipsychotics: Risperidone Butyrophenones (haloperidol) Phenothiazines (chlorpromazine) Thioxanthenes (chlorprothixene, flupenthixol) Anti-emetics: Metoclopromide Domperidone |

| Dopamine depletion | Methyldopa Reserpine Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| Inhibition of dopamine release | Codeine Heroin Morphine |

| Histamine receptor blockade | Cimetidine Famotidine Ranitidine |

| Stimulation of breast tissue and lactotrophs | Oral contraceptives |

| Mechanism unknown | Verapamil |

Persistent spontaneous discharge from a single nipple orifice is usually indicative of specific pathology involving that duct. Benign intraductal papillomas account for about 80% of single-duct bloodstained nipple discharges.2,4,5 Papillomas give rise to nipple discharge of varying colour but as these structures can bleed intermittently, papillomas are often associated with blood staining. Recent bleeding may manifest as frank blood, but stagnant bloodstained fluid can be dark red, brown or black.

Assessment

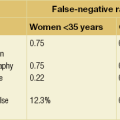

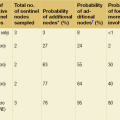

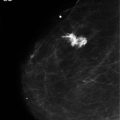

Mammography is indicated in women over the age of 35 years and may demonstrate a mass or microcalcification in association with nipple discharge of malignant aetiology. Even in younger women with bloodstained discharge, mammography can demonstrate calcification in women with widespread ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Other mammographic features may also be evident in patients with benign nipple discharge. Duct ectasia may occasionally be visible on mammography. The sensitivity of mammography in detecting pathology in nipple discharge is 57.1% (positive predictive value (PPV) of 16.7% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 91.4%).7 In a study of 306 patients with nipple discharge who had normal mammography and ultrasound, 10% were subsequently found to have underlying malignancy.7

Ductography is less widely used but is an investigation that gives clear delineation of the breast anatomy. A small amount of radio-opaque contrast is instilled into a cannulated nipple duct. Accurate detection of small filling defect(s) caused by papillomas and duct narrowing or obstruction from malignant change can be recognised. However, ductography does not provide a tissue diagnosis and the precise position of the area of interest within the breast is not usually available to the surgeon, although it is possible to target the area of abnormality with a wire localisation procedure. The use of MRI to evaluate the ductal tree is gaining interest but is not a standard investigation of nipple discharge. In a comparative study of 163 patients with nipple discharge who had normal mammography and ultrasound, ductography was found to have a PPV of 19% and an NPV of 63%. MRI was performed in 52 patients and found to have a PPV of 56% and an NPV of 87%.7

Smear cytology of nipple discharge may show the presence of malignant cells, papillary cells, red blood cells, benign duct epithelium or foam cells of macrophage origin. The available literature demonstrates sensitivities of smear cytology ranging from 11.1% to 16.7%8,9 and specificities ranging from 66.1% to 96.3%. In Simmons et al.’s study of 108 pathological specimens for nipple discharge, the PPV of smear cytology was 50% and the NPV was 76.5%.8 These data arise from an era before mammary ductoscopy when surgery providing the pathology used as the gold standard could not be targeted, so some of the pathologies present may have been missed at surgery, hence lowering the PPV of cytology. A further limitation arises when insufficient epithelial cells are available for a reliable diagnosis. This may be overcome by enhanced techniques of obtaining nipple fluid such as ductal lavage to increase the cell yield, which can improve the performance of cytological assessment.

Mammary ductoscopy and nipple discharge

MD by an experienced endoscopist can be more accurate than mammography in identifying extensive in situ disease (65% vs. 50%).10 Ling et al. found that MD-guided intraductal biopsy had a significantly higher papilloma detection rate than undirected miocrodochectomy (92.6% vs. 40.7%, P < 0.05).11 Normal findings at MD may endorse a conservative approach or alternatively facilitate a recommendation for duct transaction alone to manage symptomatic nipple discharge.

History and technology

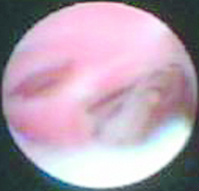

Current scopes can be flexible or rigid, with diameters that range from 0.7 to 1.2 mm (Fig. 3.1). Microendoscopes magnify up to 60 times to produce high-quality images with saline for insufflation and irrigation of the ducts. More recent developments include autofluorescence technology,12 which may help to distinguish between benign, premalignant and malignant lesions.

Technical considerations

MD, when associated with a standard surgical procedure, is often performed under general anaesthetic. Diagnostic MD can be performed as an outpatient procedure with topical local anaesthetic applied to the nipple, followed by periareolar infiltration and/or infusion down the cannulated duct, the latter facilitating relaxation of the muscle sphincters.13,14 Methylene blue dye, marking wires, clips and transillumination15 may be used for orientation, to localise lesions, guide surgical excision and facilitate pathological assessment.15–17

Intraduct appearances

There is general consensus on the intraductal appearances of common lesions from studies that have used histological correlation (Figs 3.2 and 3.3). Malignant lesions are more likely to display haemorrhagic characteristics, streaking, fissuring and irregularity of the ductal walls or present with a luminal mass that might obstruct the duct. In contrast, benign non-papillomatous lesions have a smooth, level surface without haemorrhagic features.4,18–21

Figure 3.2 A still image from mammary ductoscopy showing a large papilloma within a duct with otherwise normal epithelium.

Figure 3.3 A still image from mammary ductoscopy showing DCIS and invasive disease in branching ducts.

MD sensitivity at detecting papillomas is high at 96–97%11,19 with a PPV of 73%.21 Benign duct strictures may on occasion limit MD access.21 Sensitivity for detecting DCIS and invasive disease is lower, with reports ranging from 41% to 81%.19,22 The presence of an extensive non-invasive component associated with an invasive cancer increases significantly the likelihood of abnormal ductoscopic findings (71% vs. 16%).23

Pathological considerations

The diagnostic sensitivity of MD can be improved by incorporating ductal lavage cytology,24 which generates information from the proximal ducts that may be out of reach of the ductoscope. In a study of 415 women, the PPV of 80% of MD alone in detecting DCIS was improved to 100% by the addition of lavage cytology.25 The cell count can be further enhanced using fine brushes passed down the working channel to exfoliate intraluminal lesions under direct vision, yielding up to 33 000 cells.26,27 A cell-rich endoscopy specimen allows better discrimination between benign cells, mild to severe atypia and malignant cells. A normal duct on MD is infrequently associated with abnormal cytology.14

Reliable methods of intraductal biopsy are essential if MD is to achieve a histological diagnosis without surgical excision. Various techniques have been developed using vacuum-assisted biopsy systems, endobaskets and grasping clips.11,23,28 The intraductal breast biopsy (IDBB) system pioneered by Hunerbein and Matsunaga consists of a 0.7-mm gradient index endoscope covered by an external metal sheath containing a side opening aperture near its tip.23,28 This technique yields diagnostic material in 89–92% of cases with a sensitivity of 76.2% and a specificity of 100% for papillomas.10,23 Using biopsy clips, Ling et al. were able to produce diagnostic samples in 90% of patients.11 Biopsy techniques can be extended to perform therapeutic endoscopic papillomectomy.29,30 In two studies, IDDB stopped symptomatic nipple discharge with therapeutic efficacies of 77.6% and 95.4%.28,29 Carcinomas are associated with a lower diagnostic biopsy yield (58.3%).28 It is postulated that carcinomas are generally located more peripherally in the terminal ducts and can be difficult to access by MD.28

Limitations

In the context of nipple discharge, the majority of lesions are found within 5 cm of the nipple but up to 37% may be proximal and therefore out of the reach of a 6-cm ductoscope.15,21 Unlike other applications for microendoscopy such as the salivary gland, where there is a sizeable single-duct orifice, breast ducts open via multiple tiny orifices at or just below the nipple surface. There is variability in the number of duct systems, with one anatomy study demonstrating 29 ducts arising from 15 orifices.31 This study also found that some ducts branch within the nipple itself and may not be accessed readily by lavage cannulae or MD.

Ductoscopy and breast cancer

MD as an adjunct to breast conservation surgery for cancer is technically feasible, with high rates of tumour visualisation.13 In a subsequent publication, Dooley successfully identified the malignant lesion on MD in 150 out of 201 patients (74.6%), found additional lesions outside the planned excision site in 83 cases (41%) and decreased the positive margin rate from 23.5% to 5%.32 Louie et al. reported lower tumour visualisation rates in 6 of 14 (43%) patients and did not show any benefit of MD in reducing positive margin rates.22 The role of duct endoscopy in breast cancer management is currently limited outside clinical trials.

References

1. Baitchez, G., Gortchev, G., Todorova, A., et al, Intraductal aspiration cytology and galactography for nipple discharge. Int Surg 2003; 88:83–86. 12872900

2. Okazaki, A., Hirata, K., Okazaki, M., et al, Nipple discharge disorders: current diagnostic management and the role of fibre-ductoscopy. Eur Radiol 1999; 9:583–590. 10354867

3. Chen, L., Zhou, W.B., Zhao, Y., et al, Bloody nipple discharge is a predictor of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132(1):9–14. 21947751 This is the first meta-analysis of bloodstained nipple discharge in relation to breast cancer incidence. It showed a significant association between bloodstained nipple discharge and underlying malignancy when compared to serous or coloured discharge.

4. Kapenhas-Valdes, E., Feldman, S.M., Cohen, J.-M., et al, Mammary ductoscopy for evaluation of nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15:2720–2727. 18685898

5. Khan, S.A., Mangat, A., Rivers, A., et al, Office ductoscopy for surgical selection in women with pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18:3785–3790. 21626081

6. Dolan, R.T., Butler, J.S., Kell, M.R., et al, Nipple discharge and the efficacy of cytology in evaluating breast cancer risk. Surgeon 2010; 8:252–258. 20709281 This retrospective study of 313 patients with nipple discharge found that duct cytology was diagnostic of only 50% of underlying breast carcinoma but identified four risk factors as having a significant association with breast carcinoma: (a) age > 50 years (P < 0.0001); (b) bloody nipple discharge (P < 0.008); (c) presence of a breast lump (P < 0.0001); and (d) single-duct discharge (P < 0.006). This provides evidence in line with current expert opinion and contributes to the strong recommendation made in conjunction with Ref. 3.

7. Morrogh, M., Morris, E.A., Liberman, L., et al, The predictive value of ductography and magnetic resonance imaging in the management of nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14:3369–3377. 17896158

8. Simmons, R., Adamovich, T., Brennan, M., et al, Nonsurgical evaluation of pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2003; 10:113–116. 12620904

9. Kooistra, B.W., Wauters, C., van de Ven, S., et al, The diagnostic value of nipple discharge cytology in 618 consecutive patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009; 35:573–577. 18986790

10. Dobowy, A., Raubach, M., Topalidis, T., et al, Breast duct endoscopy: ductosocpy from a diagnostic to an interventional procedure and its future perspective. Acta Chir Belg 2011; 111:142–145. 21780520

11. Ling, H., Liu, G.Y., Lu, J.S., et al, Fiberoptic ductoscopy-guided intraductal biopsy improve the diagnosis of nipple discharge. Breast J 2009; 15:168–175. 19292803

12. Jacobs, V.R., Paepke, S., Schaaf, H., et al, Autofluorescence ductoscopy: a new imaging technique for intraductal breast endoscopy. Clin Breast Cancer 2007; 8:619–623. 17592674

13. Dooley, W.C., Endoscopic visualization of breast tumors. JAMA 2000; 284:1518. 11000644

14. Dooley, W., Francescatti, D., Clark, L., et al, Office-based breast ductoscopy for diagnosis. Am J Surg 2004; 188:415–418. 15474438

15. Dooley, W.C., Routine operative breast endoscopy for bloody nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2002; 9:920–923. 12417516

16. Escobar, P.F., Baynes, D., Crowe, J.P., Ductoscopy-assisted microdochectomy. Int J Fertil Womens Med 2004; 49:222–224. 15633479

17. Zhu, X., Xing, C., Jin, T., et al, A randomized controlled study of selective microdochectomy guided by ductoscopic wire marking or methylene blue injection. Am J Surg 2011; 201:221–225. 20870205

18. Shen, K.W., Wu, K., Lu, J.S., et al, Fiberoptic ductoscopy for patients with nipple discharge. Cancer 2000; 89:1512–1519. 11013365

19. Matsunaga, T., Ohta, D., Misak, T., et al, Mammary ductoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of intraductal lesions of the breast. Breast Cancer 2001; 8:213–221. 11668243

20. Rose, C., Bojahr, B., Grunwald, S., et al, Ductoscopy-based descriptors of intraductal lesions and their histopathologic correlates. Onkologie 2010; 33:307–312. 20523094

21. Moncrief, R.M., Nayar, R., Diaz, L., et al, A comparison of ductoscopy-guided and conventional surgical excision in women with spontaneous nipple discharge. Ann Surg 2005; 241:575–581. 15798458

22. Louie, L.D., Crowe, J.P., Dawson, A.E., et al, Identification of breast cancer in patients with pathologic nipple discharge: does ductoscopy predict malignancy? Am J Surg 2006; 192:530–533. 16978968

23. Hunerbein, M., Dubowy, A., Raubach, M., et al, Gradient index ductoscopy and intraductal biopsy of intraductal breast lesions. Am J Surg 2007; 194:511–514. 17826068

24. Denewer, A., El-Etribi, K., Nada, N., et al, The role and limitations of mammary ductoscopy in management of pathologic nipple discharge. Breast J 2008; 14:442–449. 18673337

25. Shen, K.W., Wu, J., Lu, J.S., et al, Fiberoptic ductoscopy for breast cancer patients with nipple discharge. Surg Endosc 2001; 15:1340–1345. 11727147

26. Khan, S.A., Baird, C., Staradub, V.L., et al, Ductal lavage and ductoscopy: the opportunities and the limitations. Clin Breast Cancer 2002; 3:185–191. 12196274

27. Johnson-Maddux, A., Ashfaq, R., Cler, L., et al, Reproducibility of cytologic atypia in repeat nipple duct lavage. Cancer 2005; 103:1129–1136. 15685620

28. Matsunaga, T., Kawakami, R., Namba, K., et al, Intraductal biopsy for diagnosis and treatment of intraductal lesions of the breast. Cancer 2004; 101:2164–2169. 15484220

29. Bender, O., Balci, F., Yuney, E., et al, Scarless endoscopic papillectomy of the breast. Onkologie 2009; 32:94–98. 19295246

30. Kamali, S., Bendoer, O., Aydin, M.T., et al, Ductoscopy in the evaluation and management of nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:778–783. 20012502

31. Rusby, J.E., Brachtel, E.F., Michaelson, J.S., et al, Breast duct anatomy in the human nipple: three dimensional patterns and clinical applications. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 106:171–179. 17221150

32. Dooley, W.C., Routine operative breast endoscopy during lumpectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2003; 10:38–42. 12513958