Newer Applications of Pacemakers

Pacing for Specific Cardiac Conditions

Permanent pacing has been employed to treat a variety of disorders, in addition to traditional indications of chronotropic incompetence, sick sinus syndrome, and atrioventricular (AV) block. For example, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), discussed in detail in a separate chapter, has become an important and commonly employed application for the treatment of patients with left ventricular dysfunction, congestive heart failure, and electrical dys-synchrony. Pacemakers have also played an important role in the treatment of atrial fibrillation, including providing rate support for slow ventricular response and arrhythmia suppression and after AV nodal ablation. Applications of pacemakers in the treatment of a variety of less common disorders or special situations are discussed later and are summarized in Table 119-1.

Table 119-1

Pacing for Specific Cardiac Conditions

| Cardiac Condition | Indication for Permanent Pacing |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Largely abandoned for symptoms of obstruction Indicated for AV block after ASA or SSM |

| Neurocardiogenic syncope | Limited benefit, unless very long pauses/asystole |

| Long QT syndrome | Reserved for symptomatic bradycardia ICD may be indicated for SCD or recurrent syncope |

| Muscular Dystrophies | |

| Duchenne’s | Second- or third-degree AVB (especially if wide QRS) |

| Becker | Second- or third-degree AVB (especially if wide QRS) |

| Myotonic | HV >70 millliseconds or high-degree AVB |

| Emery-Dreyfuss | Second- or third-degree AVB or unexplained syncope |

| Limb girdle | High-grade AVB or family history of AVB/SCD |

| Kearns-Sayre | Marked first-degree or high-grade AVB |

| Infiltrative Disorders | |

| Amyloidosis | First-degree or high-grade AVB, WBCL <100 bpm |

| Sarcoidosis | Symptomatic bradycardia, ICD may be indicated |

| Collagen vascular disease | Symptomatic bradycardia or high-grade AVB only |

| Lyme carditis | Usually reversible with treatment, rarely required |

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a condition characterized by disarray of myocardial fibers and myofibrils, producing excessive and inappropriate hypertrophy of the left ventricle (LV), most frequently of the interventricular septum. The hypertrophy interferes with ventricular relaxation and, in up to 25% of patients, causes dynamic obstruction across the left ventricular outflow tract. Early observational studies of right ventricular apical pacing suggested regression of ventricular hypertrophy and dramatic clinical improvement.1 However, this benefit was not substantiated in subsequent randomized controlled clinical trials,1 so this strategy has been largely abandoned, except when there is another indication for pacing, such as AV block after alcohol septal ablation (discussed later).

Neurocardiogenic Syncope

Neurocardiogenic syncope is a common problem that accounts for approximately 6% of hospital admissions in the United States annually. Despite improved diagnostic techniques, the cause of syncope remains undiagnosed in up to 50% of cases. It is likely that many of these cases are neurally mediated. The term neurocardiogenic syncope (also known as vasovagal syncope or neurally mediated syncope) is used to describe a group of related conditions that include carotid sinus hypersensitivity, post-tussive syncope, postmicturition syncope, and others. Because episodes are often accompanied by bradycardia, it was hypothesized that permanent pacing may be beneficial. Unfortunately, as with HCM, early uncontrolled studies suggested that permanent pacing offered major clinical benefits that have not been confirmed by subsequent randomized clinical trials.1,2 Currently, there is no clear clinical indication for permanent pacing in neurocardiogenic syncope. However, a subgroup of patients who experience very long pauses (>6 seconds) or marked bradycardia on ambulatory monitoring may benefit from pacing therapy.3

Chronic Disorders of the Neuromuscular System

The muscular dystrophies are a diverse group of inherited, chronic degenerative conditions primarily affecting skeletal muscle. It has long been appreciated that these disorders can also affect cardiac muscle, resulting in fibrosis and fatty replacement of the myocardium. Awareness is growing that the prevalence of arrhythmias, conduction system disease, and sudden cardiac death in these patients may warrant early intervention.4 Because these conditions are infrequent, the therapeutic guidelines are necessarily nonspecific. In general, it can be recommended that unexplained syncope, presyncope, and other transient neurologic symptoms should be aggressively investigated using ambulatory electrocardiographic recordings, long-term event recorders and loop recorders, and, in more worrisome situations (e.g., unexplained sudden syncope precipitating a motor vehicle accident), hospitalization with inpatient monitoring. In most cases, the finding of second-degree atrioventricular block, even when asymptomatic, may warrant permanent pacemaker implantation. It should be noted that ventricular tachyarrhythmias are also common in this population, so, depending on the clinical scenario, an ICD should also be considered.

1. Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy—A progressive neuromuscular disease becoming clinically manifest in the mid-teens and usually fatal by the end of the third decade, generally from heart failure. Although cardiac involvement is the rule, the conduction system is not always involved. Permanent pacing is warranted for second- or third-degree AV block, especially in the setting of a widened QRS complex.

2. Becker muscular dystrophy—Similar to Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy but more slowly progressive and with less frequent cardiac involvement. The indications for permanent pacing appear similar to those of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy.

3. Myotonic muscular dystrophy—Cardiac involvement is common and usually affects the conduction system. Published data indicate that permanent pacing is warranted with an HV interval >70 milliseconds, even in the absence of high-degree AV block.5 It has been demonstrated that patients with myotonic dystrophy who underwent an invasive approach with electrophysiological study and prophylactic pacing had a longer 9-year survival than those treated conservatively.6

4. Emery-Dreyfuss muscular dystrophy—Conduction system disease is frequent. Sudden cardiac death due to high-grade AV block has been documented, and permanent pacing should be offered with the development of any unexplained transient neurologic symptoms or second- or third-degree AV block.

5. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy—A heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by weakness in the pelvic musculature and upper legs. The familial form has a high incidence of conduction system disease, and permanent pacing should be considered in anyone with a family history of heart block or sudden death.

6. Kearns-Sayre syndrome—A multisystem disorder of the mitochondria with diverse clinical manifestations. Progressive conduction system disease is common, and permanent pacing is probably warranted for marked first-degree AV block.

Infiltrative Diseases of the Myocardium

1. Amyloidosis—Amyloidosis is characterized by deposition of an insoluble protein within the myocardium, often involving the conduction system.7 A restrictive cardiomyopathy may develop with death from congestive heart failure. Sinus node dysfunction, AV block, and intraventricular blocks are not uncommon and may require permanent pacemaker insertion if associated with symptoms. A group of 95 patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) was followed after prophylactic pacemaker insertion.8 In this series, 25% of patients developed high-degree AV block over a mean follow-up of 45 months. Predictors of development of high-grade AV block included existing first-degree AV block and Wenckebach anterograde block at ≤100 beats per minute (bpm). Therefore, prophylactic pacemaker implantation may be warranted in this population to reduce the risks of syncope and sudden death related to the development of significant conduction system disease.

2. Sarcoidosis—Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, infiltrative disorder characterized by noncaseating granulomas, which often involve the heart and the conduction system.9 This disease tends to be progressive, and the mortality of patients with extensive myocardial sarcoid is high. Permanent pacemakers may be implanted for symptomatic bradyarrhythmias, although the frequency of malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias often warrants an ICD.10

3. Collagen vascular disease—Cardiac involvement is fairly common in the collagen vascular diseases, especially polymyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Fibrosis of the conduction system may occur, and resultant AV block may require a permanent pacemaker based on standard criteria for implantation.

4. Lyme carditis—This Lyme disease spirochetal infection is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and is carried by the deer tick (Ixodes dammini). It is a systemic illness characterized by a “target”-shaped rash (erythema chronicum migrans), as well as by fever, arthralgia, myalgias, and lymphadenopathy. When untreated, this illness can result in later complications, including neurologic and cardiac involvement. Lyme carditis is typically characterized by AV block and is often reversible with antibiotic therapy, obviating the need for permanent pacing.11 To avoid unnecessary pacemaker implantation, this diagnosis should be considered by physicians when the clinical scenario occurs in an area where Lyme disease is endemic.

Permanent Pacing Post–Myocardial Infarction

In the setting of acute myocardial infarction (MI), conduction abnormalities can occur immediately or within hours to days post-infarction. Conduction abnormalities associated with inferior wall MI, including high-degree AV block, are usually secondary to heightened vagal tone in the acute phase and secondary to edema and local release of adenosine in the subacute phase (>24 hours post-infarction). Both of these scenarios are often reversible (within several days to up to 2 weeks) and, although they may warrant temporary pacing, rarely require permanent pacemaker implantation. In contrast, conduction abnormalities associated with anterior MI are often a result of infarction and necrosis of the intramyocardial conduction system. This almost always occurs in the setting of a proximal occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, and complete AV block usually occurs within the first 24 hours post-MI. Because the left anterior fascicle and the right bundle branch are supplied by septal branches of the proximal LAD, the development of bifascicular block (especially with PR prolongation) post–anterior infarction is associated with a high incidence of complete heart block and warrants empirical temporary pacemaker placement. Permanent pacemaker placement, however, is reserved for patients with high-grade AV block, including those with alternating bundle branch block and transient or persistent second- or third-degree AV block in the His-Purkinje system.12

Preventing Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction

After MI, the cardiac workload is redistributed with an increase in mechanical wall stress in ischemic and surrounding areas. These increases in wall stress are associated with left ventricular remodeling and subsequent dysfunction, as well as activation of cytokines and neurohormonal factors often associated with adverse clinical outcomes. It has been shown that pacing areas of high wall stress (“electrical preexcitation”) alters regional distribution of stroke work within the normal heart, reducing stroke work adjacent to the stimulation site and increasing stroke work in distant regions. Shuros et al. used a swine model to demonstrate that pacing from the peri-infarct area improves hemodynamics and attenuates cardiac remodeling.13 Saba et al. used a rabbit infarct model to demonstrate that biventricular pacing prevented mechanical and electrical remodeling, including preventing left ventricular systolic and diastolic function, as well as restoring QRS width. Similar beneficial effects were found in a preliminary study by Chung et al. among patients randomly assigned to biventricular pacing (compared with right ventricular stimulation).14 However, a randomized study of post-infarct pacing (The Prevention of Myocardial Enlargement and Dilatation Post Myocardial Infarction [MENDMI]) showed no effect on left ventricular dimensions.15 A larger randomized study (Post Myocardial Infarction Remodeling Prevention Therapy [PromPt]) is under way to evaluate peri-infarct pacing in greater detail.

Vagal Stimulation for Treatment of Heart Failure

Initial studies with vagal nerve stimulation demonstrated favorable changes in tissue and plasma biomarkers.16 More recently, investigators demonstrated that chronic electrical stimulation of the CSB improved LV function and promoted LV remodeling in dogs with chronic heart failure.17 This study demonstrated that chronic vagal stimulation resulted in changes at global and cellular/molecular levels, including decreased LV end-diastolic pressure, decreased circulating catecholamines, normalization of β-receptor expression, and reduced interstitial fibrosis and myocyte hypertrophy.

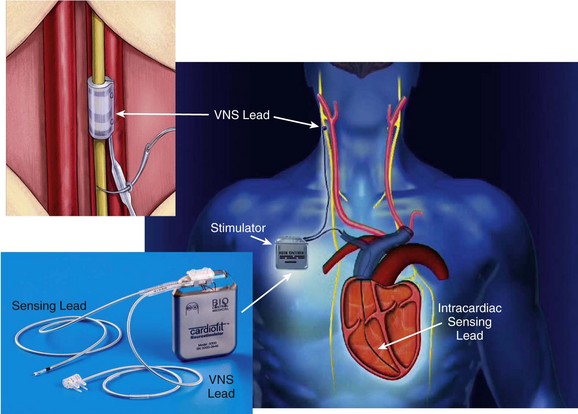

The Cardiofit Multicenter Trial was a small (n = 32), open-label study of vagal nerve stimulation in patients with severe systolic heart failure. In this study, vagal stimulation was performed using a cuff electrode and an implantable generator and was regulated according to the patient’s heart rate, using an intracardiac sensor (Figure 119-1). The results of this study demonstrated significant improvement at 6 months in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, quality of life, 6-minute walk times, and LV ejection fraction and volumes. Serious adverse events that occurred in this trial were common (40%), but only two (6%; no deaths) were directly attributable to the implant procedure and device. Current studies, including the INcrease Of Vagal TonE in Heart Failure (INOVATE-HF) study and the NEuroCardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure (NECTAR-HF) trial, are examining the effects of chronic vagal stimulation in a randomized fashion in patients with advanced heart failure who are not indicated for and did not respond to CRT.18 Results of these and other trials will whether this novel approach to treatment of chronic heart failure may provide some clinical benefit in the most refractory of cases to date.

Figure 119-1 Right, An implanted CardioFit vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) device showing the position of the VNS lead on the right vagus nerve, the intracardiac pacing lead in the right ventricular apex, and the implantable CardioFit neurostimulator in the right subclavicular region. Top left, Positioning of the CardioFit stimulation lead around the right vagus nerve. Bottom left, The CardioFit VNS implantable neurostimulator, sensing lead, and VNS lead. Courtesy BioControl Medical, Ltd., Yehud, Israel.

Indications for Pacemakers After Cardiac Procedures

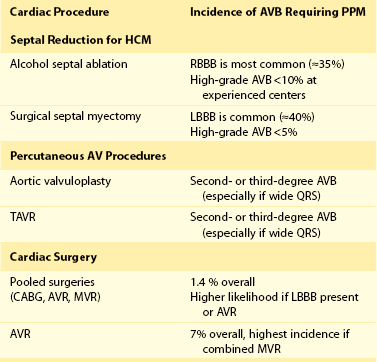

After some cardiac procedures, risk of injury to the sinus node and the AV conduction system results in symptomatic bradycardia and the need for permanent pacing. Catheter and surgical ablation of cardiac arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, is among the more common procedures associated with these risks; however, these procedures are discussed elsewhere. Table 119-2 summarizes the incidence of advanced AV block requiring permanent pacing after completion of the procedures discussed in the following sections.

Septal Reduction Procedures for HCM

Symptoms related to LV outflow tract obstruction in HCM may be treated with both surgical septal myectomy (SSM) and alcohol septal ablation (ASA). Both of these procedures have been associated with injury to the conduction system, including AV block and the need for permanent pacing. Typically, patients undergoing ASA develop a right bundle branch block (RBBB) post-procedure, whereas post-SSM patients develop left bundle branch block (LBBB). In one series, rates of RBBB and complete heart block post-ASA were 36% and 12%, respectively, whereas rates of LBBB and complete heart block after SSM were 40% and 3%, respectively.19 Predisposing contralateral BBB is an important predictor of complete AV and the need for permanent pacing after these procedures.19,20 Other factors predictive of complete heart block after ASA include female gender, multiple or bolus injections of ethanol, preexisting first-degree AV block, and acute AV block during ASA.20,21 A significant “learning curve” is likely with these procedures as the need for pacing decreases (<10%) at high-volume centers.22 Patients who require permanent pacing after these procedures derive similar clinical and hemodynamic benefit as those who do not require pacing.

Percutaneous Aortic Valve Procedures

Indications for percutaneous procedures for aortic valve disease, especially transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), are growing rapidly, and these procedures are being performed more commonly today. Because of the proximity of the aortic valve to the AV conduction system, procedures performed to treat aortic valve disease, particularly senile calcification, can lead to AV block. The incidence of new advanced AV block after balloon valvuloplasty of the aortic valve alone is low (<2%) and may be related to oversizing of the balloon employed during the procedure.23 TAVR carries a known risk of pacemaker implantation, and a recent systematic literature review demonstrated that the risk is 15% overall but appears to be higher with theCoreValve prosthesis (Medtronic Inc., Langhorne, Pennsylvania) than with the Edwards Sapiens valve (Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, Irvine, California) (odds ratio [OR] 4.91; P < .0001).24 The prevalence of new LBBB is increased after TAVR; therefore, the presence of baseline RBBB is an important predictor of AV block post-procedure. Additionally, >90% of AV block requiring long-term pacing occurs immediately or within 1 week post-procedure, suggesting that this is due to direct mechanical injury to the conduction system during valve implantation.

Cardiac Surgery

The requirement for acute pacing after cardiac surgery is common (10% to 15%); however, most of these conditions will recover, and only 1% to 3% of patients will require permanent pacing postoperatively. In a recent review of almost 5000 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (81% coronary bypass surgery, 14% aortic valve replacement, 18% mitral valve replacement), the incidence of new permanent pacing postoperatively was 1.4%.25 Indications for pacing consisted predominantly of high-grade AV block, and approximately  of patients were pacemaker dependent at 6-year follow-up. Predictors of required permanent pacing included baseline LBBB and aortic valve replacement. In another series, 7% of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement required permanent pacing postoperatively, 70% of whom were pacemaker dependent at follow-up.26 Patients who had baseline first-degree AV block with or without left anterior fascicular block or intraventricular conduction delay, as well as those who underwent combined aortic and mitral valve replacement, had the highest risk of permanent pacing. Surgery for congenital heart disease can be very complex and may result in damage to the conduction system requiring permanent pacing.

of patients were pacemaker dependent at 6-year follow-up. Predictors of required permanent pacing included baseline LBBB and aortic valve replacement. In another series, 7% of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement required permanent pacing postoperatively, 70% of whom were pacemaker dependent at follow-up.26 Patients who had baseline first-degree AV block with or without left anterior fascicular block or intraventricular conduction delay, as well as those who underwent combined aortic and mitral valve replacement, had the highest risk of permanent pacing. Surgery for congenital heart disease can be very complex and may result in damage to the conduction system requiring permanent pacing.

Novel Approaches and Technology for Cardiac Pacing

Leadless Pacemakers

It is well established that the “weak link” in a pacemaker system consists of the leads required for sensing and carrying electrical impulses from the pulse generator to the cardiac tissue. Lead failure occurs in up to 20% of patients within 10 years of implantation.27 Additionally, risks of vascular occlusion, pacemaker lead–associated endocarditis, and extraction procedures when leads fail make the concept of leadless pacing technologies attractive.

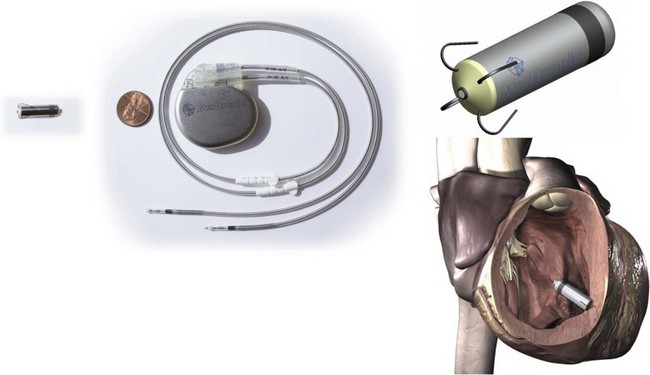

One approach that is in development employs a miniaturized device that is completely implantable within the heart, thus eliminating the need for a pocket or leads. Such technology was first proposed by Spickler et al. in 1970.28 More recently, animal studies with a completely intracardiac device have demonstrated stable, reasonable thresholds and no dislodgements or other clinical complications.29 Initial versions of these devices will be implanted in the right ventricular apex (Figure 119-2). Challenges in the development of a miniaturized pacemaker system will include the ability to produce sequential (i.e., AV) pacing between devices implanted in different chambers, ability for extraction, and the need for approaches for device replacement at battery depletion.

Figure 119-2 Miniaturized Leadless Pacemaker

Left, Leadless pacemaker size compared with a standard dual-chamber pacemaker. Top right, Model of miniaturized leadless pacemaker. Bottom right, Leadless pacemaker implant location. (Reproduced with permission from Medtronic, Inc.)

Another area of research and development involves external transmission of an energy source to a stand-alone intracardiac transducer localized in the chamber to be paced. Wienke et al. successfully showed that induction technology can be used for cardiac pacing; they employed alternating magnetic fields to generate voltage pulses in a receiver screwed into the right ventricular apex.27 Ultrasound technology has also been used to generate pacing with consistent capture from a receiver electrode in the right atrium, right ventricle, and left ventricle.30 Investigators have studied ultrasound stimulation for left ventricular pacing in heart failure patients, demonstrating reliable capture and predictable acoustic windows during positional changes and respiration to guide development of future implantable devices.31 Unfortunately, initial human studies of these systems were stopped prematurely because of serious complications associated with left ventricular transducer implantation.

Biological Pacemakers

The notion of using a biological pacemaker to replace an electronic pacemaker may be attractive, potentially avoiding the expense and complications associated with device replacement, device or lead failure, and infection; however, despite their limitations, electronic pacemakers are effective and durable and have withstood the test of time for over five decades. “Niche” applications such as use in patients with chronic infection, loss of vascular access, or other “bridge-to-device” applications may be suitable for a biological pacemaker. Approaches such as gene therapies, gene-cell hybrid approaches, and use of stem cells have been proposed and tested to convert nonexcitable cells into self-contained biological pacemakers through ion channel expression.32 Future research will focus on generating the cells necessary to generate action potentials reliably with automaticity and on developing delivery systems and avoiding pitfalls such as the durability of these systems over time and the potential tumorigenicity of stem cells.

References

1. Gold, M, Peters, RW. Newer applications of pacemakers. In Zipes DP, ed. : Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside, ed 5, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

2. Connolly, SJ, Sheldon, R, Thorpe, KE, et al. Pacemaker therapy for prevention of syncope in patients with recurrent severe vasovagal syncope: Second Vasovagal Pacemaker Study (VPS II): A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003; 289:2224–2229.

3. Brignole, M, Menozzi, C, Moya, A, et al. Pacemaker therapy in patients with neurally mediated syncope and documented asystole: Third International Study on Syncope of Uncertain Etiology (ISSUE-3): A randomized trial. Circulation. 2012; 125:2566–2571.

4. Groh, WJ. Arrhythmias in the muscular dystrophies. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:1890–1895.

5. Lazarus, A, Varin, J, Babuty, D, et al. Long-term follow-up of arrhythmias in patients with myotonic dystrophy treated by pacing: A multicenter diagnostic pacemaker study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40:1645–1652.

6. Wahbi, K, Meune, C, Porcher, R, et al. Electrophysiological study with prophylactic pacing and survival in adults with myotonic dystrophy and conduction system disease. JAMA. 2012; 307:1292–1301.

7. Shah, KB, Inoue, Y, Mehra, MR. Amyloidosis and the heart: A comprehensive review. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166:1805–1813.

8. Algalarrondo, V, Dinanian, S, Juin, C, et al. Prophylactic pacemaker implantation in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Heart Rhythm. 2012; 9:1069–1075.

9. Doughan, AR, Williams, BR. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart. 2006; 92:282–288.

10. Kim, JS, Judson, MA, Donnino, R, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:9–21.

11. McAlister, HF, Klementowicz, PT, Andrews, C, et al. Lyme carditis: An important cause of reversible heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:339–345.

12. Zimetbaum, PJ, Josephson, ME. Use of the electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:933–940.

13. Shuros, AC, Salo, RW, Florea, VG, et al. Ventricular preexcitation modulates strain and attenuates cardiac remodeling in a swine model of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007; 116:1162–1169.

14. Chung, ES, Menon, SG, Weiss, R, et al. Feasibility of biventricular pacing in patients with recent myocardial infarction: Impact on ventricular remodeling. Congest Heart Fail. 2007; 13:9–15.

15. Chung, ES, Dan, D, Solomon, SD, et al. Effect of peri-infarct pacing early after myocardial infarction: Results of the prevention of myocardial enlargement and dilatation post myocardial infarction study. Circ Heart Fail. 2010; 3:650–658.

16. Sabbah HRS, Hamman J, Gupta R, et al: Chronic vagal nerve stimulation impacts biomarkers of heart failure in canines. Presented at: American College of Cardiology, Scientific Sessions; Orlando, Florida; November 14-18, 2009. Abstract 12792.

17. Sabbah, HN, Gupta, RC, Imai, M, et al. Chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus baroreflex improves left ventricular function and promotes reversal of ventricular remodeling in dogs with advanced heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011; 4:65–70.

18. Zannad F FG, Brugada J, Butler C, et al: NECTAR-HF: NEuroCardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure. Presented at: ESC Heart Failure Scientific Session; Gothenburg, Sweden; May 21-24, 2011.

19. Talreja, DR, Nishimura, RA, Edwards, WD, et al. Alcohol septal ablation versus surgical septal myectomy: Comparison of effects on atrioventricular conduction tissue. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:2329–2332.

20. Chang, SM, Nagueh, SF, Spencer, WH, 3rd., et al. Complete heart block: Determinants and clinical impact in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy undergoing nonsurgical septal reduction therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42:296–300.

21. Chen, AA, Palacios, IF, Mela, T, et al. Acute predictors of subacute complete heart block after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006; 97:264–269.

22. Fernandes, VL, Nielsen, C, Nagueh, SF, et al. Follow-up of alcohol septal ablation for symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: The Baylor and Medical University of South Carolina experience, 1996 to 2007. J Am Coll Cardiol Cardiovasc Interv. 2008; 1:561–570.

23. Laynez, A, Ben-Dor, I, Hauville, C, et al. Frequency of cardiac conduction disturbances after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108:1311–1315.

24. Erkapic, D, De Rosa, S, Kelava, A, et al. Risk for permanent pacemaker after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A comprehensive analysis of the literature. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23:391–397.

25. Merin, O, Ilan, M, Oren, A, et al. Permanent pacemaker implantation following cardiac surgery: Indications and long-term follow-up. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32:7–12.

26. Huynh, H, Dalloul, G, Ghanbari, H, et al. Permanent pacemaker implantation following aortic valve replacement: Current prevalence and clinical predictors. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32:1520–1525.

27. Wieneke, H, Konorza, T, Erbel, R, et al. Leadless pacing of the heart using induction technology: A feasibility study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009; 32:177–183.

28. Spickler, JW, Rasor, NS, Kezdi, P, et al. Totally self-contained intracardiac pacemaker. J Electrocardiol. 1970; 3:325–331.

29. Bonner MEM: Chronic animal study of leadless pacer design. Heart Rhythm Scientific Sessions; San Francisco, Caifornia; May 5-7, 2011. Abstract 6163.

30. Lee, KL, Lau, CP, Tse, HF, et al. First human demonstration of cardiac stimulation with transcutaneous ultrasound energy delivery: Implications for wireless pacing with implantable devices. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:877–883.

31. Lee, KL, Tse, HF, Echt, DS, et al. Temporary leadless pacing in heart failure patients with ultrasound-mediated stimulation energy and effects on the acoustic window. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:742–748.

32. Cho, HC, Marban, E. Biological therapies for cardiac arrhythmias: Can genes and cells replace drugs and devices? Circ Res. 2010; 106:674–685.

33. Sabbah, HN. Electrical vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Cleveland Clin J Med. 2011; 78(Suppl 1):S24–S29.