Newborn and Early Childhood Respiratory Disorders

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the clinical manifestations common with newborn and early childhood respiratory disorders, including the following:

• Clinical manifestations associated with increased negative intrapleural pressures during inspiration

• Flaring nostrils (or nasal flaring)

• Describe the meaning of apnea of prematurity.

• List factors that trigger apnea in the premature infant.

• Describe persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN).

• Describe the arterial blood gas values commonly associated with newborn respiratory disorders, and include the three major mechanisms responsible for the decreased Pao2 associated with newborn pulmonary disorders.

• Discuss the objective data, assessments, and treatment plans commonly associated with newborn respiratory disorders.

• Describe the major components of the Apgar score.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Clinical Manifestations Common with Newborn and Early Childhood Respiratory Disorders

Clinical Manifestations Associated with More Negative Intrapleural Pressures during Inspiration

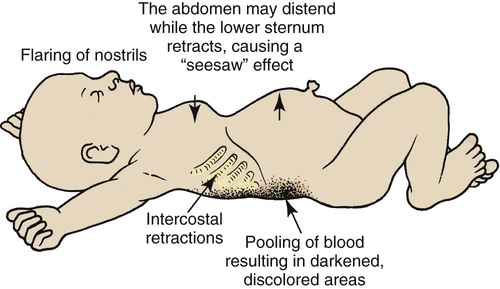

The thorax of the newborn infant is quite flexible—that is, the compliance of the infant’s thorax is high. This flexibility is a result of the large amount of cartilage found in the skeletal structure of newborns. Because of the structural alterations associated with many newborn respiratory disorders, however, the compliance of the infant’s lungs is low. In an effort to offset the decreased lung compliance, the infant must generate more negative intrapleural pressures during inspiration. This condition causes the following (see Figure 31-1):

• The soft tissues between the ribs retract during inspiration.

• The substernal area retracts and the abdominal area protrudes in a seesaw fashion during inspiration. The substernal retraction is caused by high negative intrapleural pressure, and the abdominal distention is caused by the contraction (depression) of the diaphragm during inspiration.

• The blood vessels in the more dependent portions of the thoracic and abdominal areas dilate and pool blood, causing these areas to appear cyanotic.

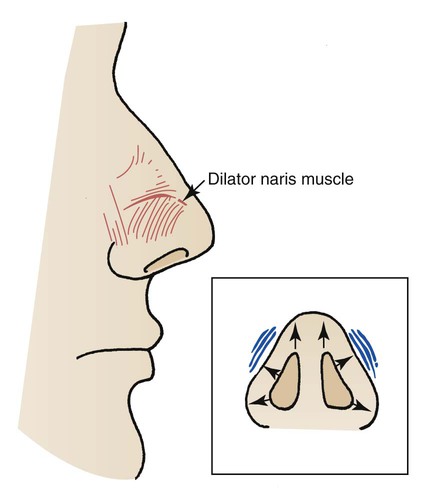

Flaring Nostrils (or Nasal Flaring)

Flaring nostrils (or nasal flaring) frequently are observed in infants in respiratory distress. This clinical manifestation probably is a facial reflex to facilitate the movement of gas into the tracheobronchial tree. The dilator naris, which originates from the maxilla and inserts into the ala of the nose, is the muscle responsible for this movement. When activated, the dilator naris pulls the alae laterally and widens the nasal aperture, providing a larger orifice for gas to enter during inspiration (Figure 31-2).

Apnea of Prematurity

Premature infants are believed to be susceptible to apneic episodes because of immature functioning of the chemoreceptors, receptors in the airways, and central nervous system. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep also is thought to play an important role in causing sleep apnea. Box 31-1 lists factors that trigger apneic episodes.

Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) is commonly seen in infants with an underlying respiratory disorder such as pneumonia, meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), or RDS. Box 31-2 lists disorders commonly associated with PPHN.

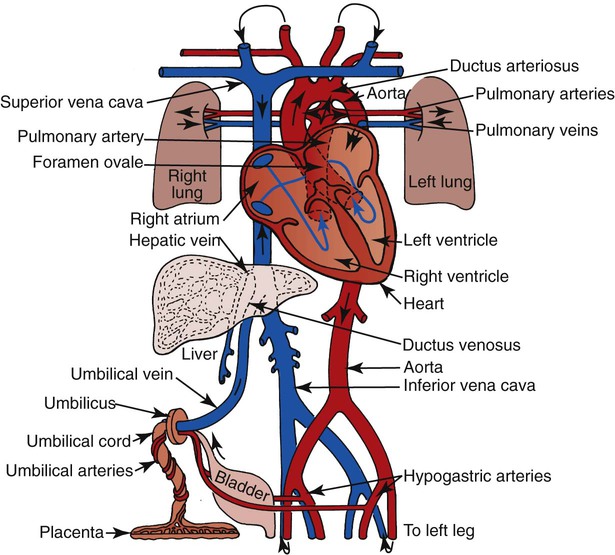

PPHN is caused in part by reflex pulmonary vasoconstriction, which can be activated by myriad stimuli, including alveolar hypoxia, hypercapnia, and decreased pH. As a result of the high pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), right-to-left shunting develops—that is, mixed venous blood bypasses the infant’s lungs via the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale (see fetal circulation pathways, Figure 31-3).

Assessment of the Newborn

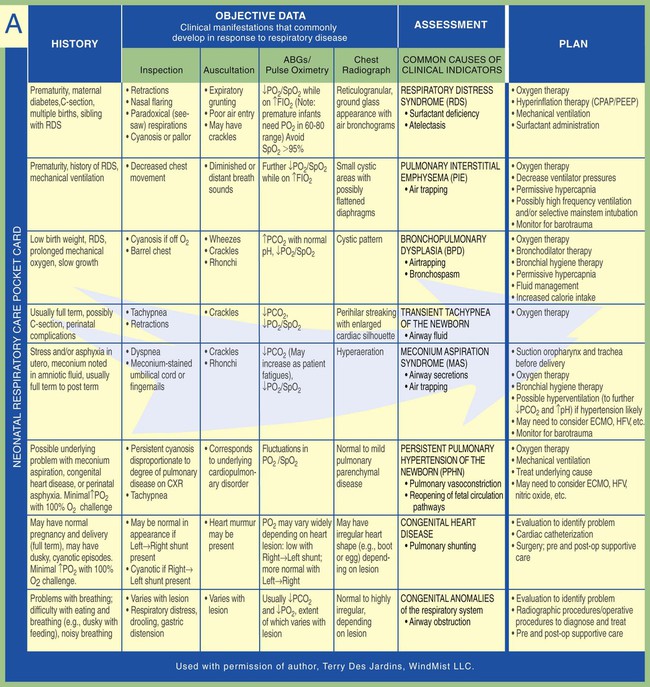

As already discussed in Chapter 10, good assessment skills include (1) the systematic collection of clinical data, (2) the evaluation of the data, and (3) the formulation of an appropriate treatment plan. As with the older child or adult, the newborn with respiratory disease must be evaluated frequently. To enhance this process, Figure 31-4 illustrates objective data, assessments, and treatment plans commonly associated with newborn respiratory disorders. Another common assessment tool for the newborn is the Apgar score.

Apgar Score

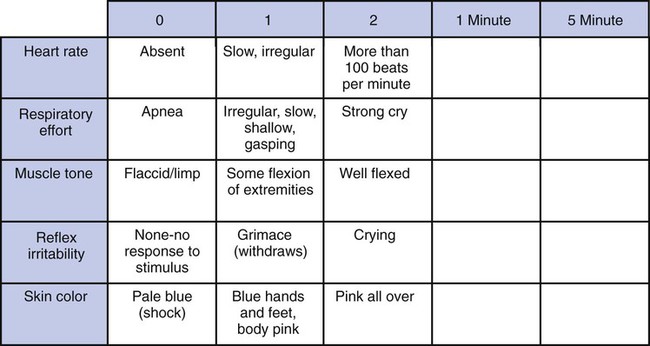

The Apgar score is a rating system for the rapid identification of infants requiring immediate intervention or transfer to an NICU. The Apgar evaluation is performed 1 minute after birth and again 5 minutes later. It is based on a rating of five factors that reflect the infant’s ability to adjust to extrauterine life. As shown in Figure 31-5, the infant’s heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color are scored from a low value of 0 to a normal value of 2. The five scores are combined and the totals at 1 minute and 5 minutes are recorded. For example, Apgar 8/10 is a score of 8 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes.

, and a decrease in the pH. The decreased pH also may result from the decreased Pa

, and a decrease in the pH. The decreased pH also may result from the decreased Pa reading and pH will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

reading and pH will be lower than expected for a particular Pa