CHAPTER 15 New Techniques in Elbow Arthroscopy

Elbow arthroscopy was pioneered during the early 1980s, but it came to increased prominence after Andrews and Carson’s 1985 paper,1 which described the anatomy of the elbow joint as seen through the arthroscope and demonstrated the feasibility of arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the elbow. Further works by Morrey,2 Lynch and colleagues,3 Poehling and coworkers,4 and O’Driscoll and Morrey5 secured the procedure as an accepted orthopedic practice. Initial concerns about the potential for neurologic injury remain the primary concern of elbow arthroscopists today, and thorough knowledge of the neurovascular anatomy of the elbow is essential for performing elbow arthroscopy safely.

THE STIFF ELBOW

Intra-articular pathology, such as intra-articular fibrosis, causing elbow stiffness may be amenable to arthroscopic treatment, but the prognosis may be limited.

Intra-articular pathology, such as intra-articular fibrosis, causing elbow stiffness may be amenable to arthroscopic treatment, but the prognosis may be limited. Capsular contracture is the pathology most easily treated with arthroscopy, and it therefore carries the best prognosis.

Capsular contracture is the pathology most easily treated with arthroscopy, and it therefore carries the best prognosis. Extra-articular causes of elbow stiffness, such as heterotopic ossification, are not amenable to arthroscopic management. The prognosis is mixed.

Extra-articular causes of elbow stiffness, such as heterotopic ossification, are not amenable to arthroscopic management. The prognosis is mixed.We prefer to position the patient in a lateral position with the arm flexed at the elbow 90 degrees over a fixed bolster (Fig. 15-1). A 30-degree, 4.0-mm arthroscope without side-venting cannulas is most often used, but a 2.7-mm arthroscope can make visualization of the lateral gutter easier, and a 70-degree scope may add perspective in tight joints.

Capsule distention is performed easily and safely through the lateral soft spot. The normal joint can accommodate about 30 mL of fluid at 70 degrees of flexion, but in patients with joint contracture, this amount is significantly decreased and averages only 6 mL at 85 degrees. The capsule is also about 15% less compliant in these cases, and it is often thickened.6 Although capsule distention can increase the safety of portal placement by increasing the distance from the articulation to related neurovascular structures, the distance from the capsule to these structures remains unchanged and does not protect the neurovasculature during capsulectomy or capsular release.

We think the safest method of making portals is to incise sharply through the epidermis and dermis and bluntly dissect through the depths of the subcutaneous fat layers. This minimizes damage to cutaneous nerves that are found in the very depth of the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 15-2).7

Three types of anterior capsular releases have been reported:

A capsulotomy is performed superiorly from medial to lateral. It is performed proximally to minimize the chance of radial nerve injury, and it is usually performed with cautery or a hook knife.

A capsulotomy is performed superiorly from medial to lateral. It is performed proximally to minimize the chance of radial nerve injury, and it is usually performed with cautery or a hook knife. In a linear capsulectomy, a strip of the proximal capsule is excised with a basket forceps or a resector.8

In a linear capsulectomy, a strip of the proximal capsule is excised with a basket forceps or a resector.8 In a radical capsulectomy, the entire anterior capsule is excised. To perform this safely, the radial nerve requires exploration.9

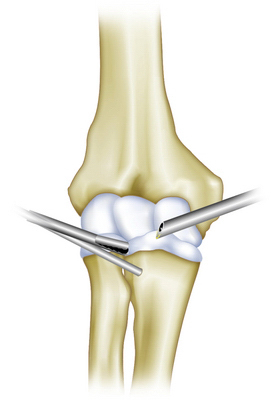

In a radical capsulectomy, the entire anterior capsule is excised. To perform this safely, the radial nerve requires exploration.9We prefer to perform a capsulectomy rather than a simple release to reduce the risk of recurrence. If the surgeon wishes to identify the radial nerve before excising the adjacent capsule, we recommend the use of two medial portals and a lateral retractor to protect nervous tissue (Fig. 15-3). Our preferred technique is to excise the medial one half of the capsule first. A mini-Hohmann retractor is then introduced through the medial portal. An arthroscope is placed in the medial superior portal with the retractor in the medial inferior portal. The capsule can then be teased off the brachialis muscle using blunt dissection. The blunt-ended retractor can be rotated to identify this natural interval. The radial nerve can be safely retracted anteriorly by advancing the retractor toward the lateral side. After this interval is developed, a second retractor is passed through the anterolateral portal and passed between the capsule and the first retractor, which can be removed. At this point, the capsulectomy can be safely completed. The capsulectomy should not proceed unless the nerve can be clearly visualized and protected with the Hohmann retractor.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Management and Rehabilitation

The range of motion achieved intraoperatively should be accurately recorded. The aim is to achieve this range as early as possible postoperatively. Good postoperative analgesia is essential, and the use of nerve blocks can be useful. Range-of-motion exercises should be active whenever possible. Continuous passive motion (CPM) or night splinting is advocated by some surgeons, but it is not used in our practice. Although CPM has been shown to mildly improve active flexion in open capsulectomy, mean active extension is unaffected, and it is often poorly tolerated.10 We implement a 14-day course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication to minimize the risk of heterotopic bone formation and to reduce pain and swelling. We have used turnbuckle splints in more severe cases and for patients for whom rehabilitation has been slow.

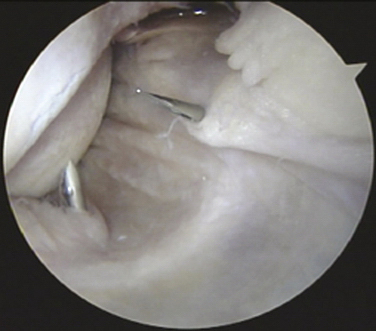

ASSESSMENT OF ELBOW INSTABILITY

Elbow arthroscopy is performed in all patients. The elbow is assessed with the arthroscope in the anteromedial portal. A rent may be seen of the lateral ligament complex from the humerus, which often tears off as a sleave.11 This rent is the best sign of posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) when viewing from the anterior compartment. The capsule sits on the capitellum and therefore does not heal back to the lateral epicondyle. Scuffing of the radial head or capitellum humeri may be seen.

We use arthroscopy to classify patients with PLRI in three groups. Those with isolated PLRI are managed with a lateral reconstruction. Those with associated medial joint space opening are managed with a circumferential graft to reconstruct the medial and lateral collateral ligaments.12 The third group of patients has degenerative changes, and their management is governed by the degree of instability and osteoarthrosis.

SOFT TISSUE LESIONS OF THE ELBOW

Ulnar Neuritis

Ulnar neuritis is the second most common entrapment neuropathy of the upper limb. Various techniques have been described for performing endoscopic ulnar nerve decompression at the elbow. We prefer to use the Agee Micro-Aire device (LMT, Taringa, Queensland, Australia). A cadaveric study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this technique.13

With the patient under general anesthesia and placed in the lateral position with the elbow flexed over a padded bar and an upper arm tourniquet inflated, a 3-cm incision is made between the olecranon and medial epicondyle. Blunt dissection is performed to the cubital retinaculum. A small fenestration is performed to allow insertion of the Agee device adjacent to the nerve under direct vision. The device is used proximally and distally to divide the cubital retinaculum. The device is gently manipulated until the retinaculum is clearly visible and inspection shows that the nerve and its branches are not threatened. Activating the trigger mechanism advances the blade, and the entire device is carefully withdrawn to incise the retinaculum. The blade can be rapidly retracted by release of the trigger if any important structures come into view. The endoscope is then reintroduced to assess the adequacy of the decompression.

Biceps Tendon Bursoscopy

Distal biceps tendon bursoscopy may be indicated for patients presenting with symptoms of biceps bursitis or those with a suspected partial-thickness tear of the distal biceps tendon. The bicipitoradial bursa surrounds the distal biceps tendon. It is adherent to the radial aspect of the biceps tendon and drapes around the tendon before attaching circumferentially to the radius at the tendon-bone interface.14

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with an inflated upper arm tourniquet. The arm is positioned in extension and supination. A 2.5-cm longitudinal incision commencing 2 cm distal to the anterior elbow crease is performed over the palpable biceps tendon. Care is taken to protect the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm. The bursa is identified surrounding the distal biceps tendon. The bursa can be inflated with 7 to 10 mL of saline. The trocar and cannula of the arthroscope are inserted into the apex of the bursa on its radial side, and the arthroscope is inserted. Inflation is maintained with saline by gravity feed.15

The bursa can be visualized to confirm the diagnosis of bursitis (Fig. 15-4). The biceps tendon insertion is examined for partial tears. Bursectomy or débridement of partial-thickness tears can be performed using a toothless, full-radius oscillating chondrotome. This should be performed without suction to avoid injury to neurovascular structures.

Olecranon Bursoscopy

Olecranon bursoscopy is discussed in detail in Chapter 5. We have modified our technique to protect the overlying skin when resecting the inflamed or infected bursa.

With the patient placed in the lateral position under general anesthesia and an upper arm tourniquet inflated, two 1.5-cm longitudinal incisions are made in the midline 3 cm proximal and distal to the margins of the bursa (Fig. 15-5). Blunt dissection is performed in the subcutaneous plane using Metzenbaum scissors to connect the two incisions, separating the cutaneous tissue from the bursa. Bursectomy can be safely performed using a toothed, oscillating chondrotome, which should be used with the jaws facing the bursa, away from the skin. The bursectomy is performed from the subcutaneous plane and directed toward the olecranon. The procedure is complete when the fibers of the triceps tendon are visible. Care must be taken not to weaken this insertion. Distention of the subcutaneous field can be facilitated by passing a tape or suture through from one portal to the other and applying traction or with the use of disposable arthroscopy portals placed in the dependent (distal) incision.

Ganglia

Synovial cysts (i.e., ganglia) of the elbow joint can rarely be found in patients with osteoarthrosis or rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 15-6). Most can be managed nonoperatively. For patients with persistent symptoms, surgery may be advised. Other indications include compression of neurologic structures of the elbow by the mass affect of the ganglion.16 Feldman reported the first case of a ganglion cyst of the elbow treated with arthroscopic excision.17

FIGURE 15-6 Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a multilocular ganglion cyst arising from the elbow joint.

(From Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:477-480.)

The procedure is performed through standard arthroscopy portals. Excision can be facilitated by the addition of another portal anterior and distal to the anterolateral portal, through which a transfixing Wissinger rod can be inserted to distract the anterior neurovascular bundle away from the operating field.16,18 The transfixing rod can protect neurologic structures, improve the arthroscopic view, and facilitate excision. We emphasize the importance of complete excision of the cyst lining to prevent recurrence (Fig. 15-7).

FIGURE 15-7 Diagrammatic view of the Wissinger rod inserted anterior and distal to the anterolateral portal.

(Modified from Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:477-480.)

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

BENIGN INTRA-ARTICULAR LESIONS

Osteoid Osteoma

Arthroscopic techniques can be used for the treatment of intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the elbow. Although this diagnosis is rare, the location of the lesions can render them entirely suitable for arthroscopic excision (Fig. 15-8).

Nourissat and colleagues19 reported two cases of osteoid osteoma, one on the capitellum and the other on the trochlea in patients 20 and 27 years old, respectively. The procedure was performed with the patient under general anesthesia and in the lateral decubitus position. The lesion was removed with a curette (Fig. 15-9), producing complete resolution of symptoms by 2 weeks. One patient had an early, symptomatic recurrence of the lesion. This was attributed to the surgical technique. The surgeons thought that use of the chondrotome shaver for excision led to incomplete excision.

FIGURE 15-9 The arthroscopic view demonstrates the use of a curette for en bloc excision.

(From Nourissat G, Kakuda C, Dumontier C. Arthroscopic excision of osteoid osteoma of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;23: 799e1-799e4.)

The surgeon also should consider image-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. It is an established technique for the treatment of osteoid osteoma when accessible.20

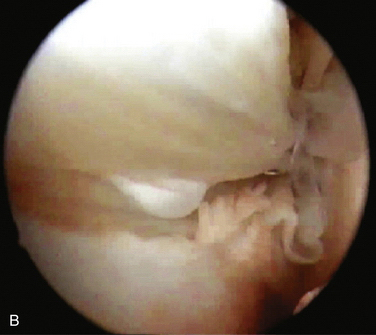

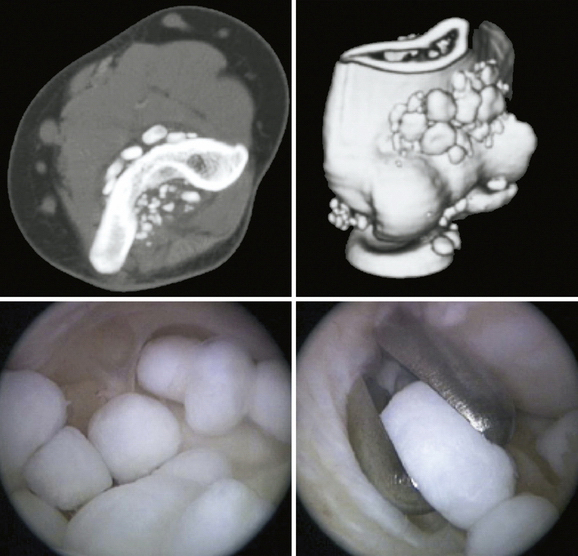

Synovial Chondromatosis

Synovial chondromatosis is a rare condition that can be a primary condition or result from an underlying pathology, such as osteoarthrosis or osteochondritis dissecans. It is caused by metaplasia of synoviocytes. Histologically, the condition is characterized by synovitis with foci of newly formed cartilage. The patient presents with pain and swelling of the elbow. Episodes of locking occur because of cartilage bodies that develop within the joint.

Standard care involves removal of chondral bodies (often described as loose, although most remain bound to the synovium) and partial synovectomy, which may be performed as an open or an arthroscopic procedure. Arthroscopy is advocated because synovectomy can be performed with less trauma to the surrounding tissues,21 but it does require advanced arthroscopic skills to perform safely and adequately.

The procedure is performed through standard arthroscopy portals. Removal of sizeable chondral lesions that cause mechanical symptoms is mandatory (Fig. 15-10). The synovectomy should be as extensive as is safe to perform, but affected tissue often remains in the medial and lateral gutters.21,22

Flury and colleagues23 reported the largest series of arthroscopic treatment of synovial chondromatosis. Fourteen adult patients with a mixture of primary and secondary chondromatosis of the elbow were reviewed retrospectively at an average of 39 months (range, 11 to 70 months) after arthroscopic synovectomy. This group was compared with five patients treated at the same center using open techniques. No differences in outcome were reported using validated outcome measures, although the investigators acknowledged the power limitations of the study. None of the patients had recurrence of chondral lesions on radiographic review. Two patients had some recurrence of symptoms that were attributed to underlying osteoarthrosis. The study authors suggest that the rehabilitation time was shorter for the arthroscopic group.

1. Andrews JR, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97-107.

2. Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:102-107.

3. Lynch GJ, Meyers JF, Whipple TL, Caspari RB. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:190-197.

4. Poehling GG, Whipple TL, Sisco L, Goldman B. Elbow arthroscopy: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:222-224.

5. O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:84-94.

6. O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF, An KN. Intraarticular pressure and capacity of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:100-103.

7. Dowdy PA, Bain GI, King GJ, Patterson SD. The midline posterior elbow incision. An anatomical appraisal. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:696-699.

8. Ball CM, Meunier M, Galatz LM, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow contracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624-629.

9. O’Driscoll SW. Operative treatment of elbow arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1995;7:103-106.

10. Gates HS 3rd, Sullivan FL, Urbaniak JR. Anterior capsulotomy and continuous passive motion in the treatment of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:1229-1234.

11. Mehta JA, Bain GI. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:405-415.

12. van Riet RP, Bain GI, Baird R, Lim YW. Simultaneous reconstruction of medial and lateral elbow ligaments for instability using a circumferential graft. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2006;10:239-244.

13. Bain GI, Bajhau A. Endoscopic release of the ulnar nerve at the elbow using the Agee device: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:691-695.

14. Eames MH, Bain GI, Fogg QA, van Riet RP. Distal biceps tendon anatomy: a cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1044-1049.

15. Eames MH, Bain GI. Distal biceps tendon endoscopy and anterior elbow arthroscopy portal. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:139-142.

16. Mileti J, Largacha M, O’Driscoll SW. Radial tunnel syndrome caused by ganglion cyst: treatment by arthroscopic cyst decompression. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:e39-44.

17. Feldman MD. Arthroscopic excision of a ganglion cyst from the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:661-664.

18. Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Lee YS, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:477-480.

19. Nourissat G, Kakuda C, Dumontier C. Arthroscopic excision of osteoid osteoma of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:799e1-799e4.

20. Venbrux AC, Montague BJ, Murphy KP, et al. Image-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for osteoid osteomas. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:375-380.

21. Bynum CK, Tasto J. Arthroscopic treatment of synovial disorders in the shoulder, elbow, and ankle. J Knee Surg. 2002;15:57-59.

22. Byrd JW. Arthroscopy of the elbow for synovial chondromatosis. J South Orthop Assoc. 2000;9:119-124.

23. Flury MP, Goldhahn J, Drerup S, Simmen BR. Arthroscopic and open options for surgical treatment of chondromatosis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:520-525e1.