126 Nevi

Clinical Manifestation And Management

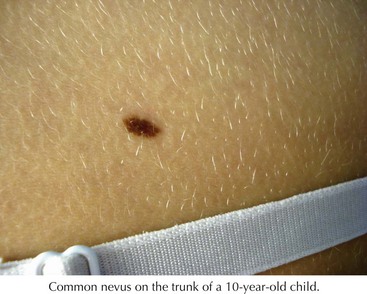

Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi

Common nevi typically begin to develop in early childhood, and new nevi may continue to arise into the third decade (Figure 126-1). These lesions have a variety of presentations depending on where the nests of nevus cells reside, and they are named accordingly. Those with nevus cells at the dermal-epidermal junction are known as junctional nevi, and those with nevus cells in the dermis are intradermal nevi. Those with cells in both compartments are called compound. The shapes and sizes vary, but most are smaller than 6 mm in size. They are more common in sun-exposed areas, where increased sun exposure leads to more moles in these areas. In general, children with lighter pigmented skin have more nevi than those with darkly pigmented skin. Children with families with increased nevi also have more moles, suggesting a genetic component to the total number of lifetime moles acquired. Studies in first-degree relatives and twins suggest that genetic factors have a significant impact on the number of moles independent of skin color or sun exposure.

Dysplastic or Atypical Nevi

These are atypical nevi that have some asymmetry, size larger than 6 mm, variable color, and irregular borders (Figure 126-2). They frequently contain both a macular and papular component and variegated color (pink, brown, tan). They show architectural disorder histologically and are categorized by many pathologists as mildly, moderately, or severely atypical. Atypical moles typically begin to develop around puberty. The tendency to develop these nevi is genetic, with some families having multiple atypical nevi but no family history of melanoma but other families having both an increased risk of atypical moles and melanoma (familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome [FAMM]).

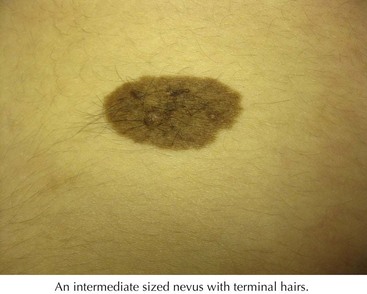

Congenital Nevi

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are characterized by being present at birth or within a few months of birth. Rarely, they do not become visible until up to 2 years of age. Congenital nevi are divided into giant (>20 cm), medium (1.5-2 0cm), and small (<1.5 cm). The colors of CMNs are variable with a range from tan to black. CMNs change over time. At birth and during early infancy, they may appear more uniform in color and flat. With time, they can become elevated and developed variegated pigmentation and a rough surface. Nodules and papules can develop within the lesion, and although most of these are benign, they need to be evaluated for malignant transformation. Over time, they can also develop dark terminal hairs (Figure 126-3).

The management of small and medium melanocytic nevi is controversial. The lifetime risk of developing melanoma is somewhere between 0% and 5%, and it is rare to undergo malignant transformation in childhood. Lesions can be followed and surgically removed in later childhood when the child can participate in the decision. The risk for melanoma increases in puberty. If it is decided not to remove the lesion, serial examinations and photographs should be used for evaluation. Surgery should be considered sooner if it is burdensome to follow the lesion for the patient and family or anxiety is high. If a change is noted, the lesion should be biopsied. Patients and their families should be aware of CMN support groups such as Nevus Network (www.nevusnetwork.org).

Special Nevi

Blue Nevus

These are blue papules or nodules that typically begin in adolescence and grow slowly (Figure 126-4). They are composed of dermal melanocytes and melanophages, and the depth of the melanocytes in the dermis accounts for their blue color. There are three variants: common, cellular, and epitheloid. The common type is usually solitary on the dorsal hands and feet and occasionally the face. The cellular type has a predilection for the buttock and sacral region and occasionally is present at birth. Epithelioid blue nevi can be numerous and can be seen in Carney’s complex (a disorder of myxomas, lentigines, endocrine abnormalities or neoplasms, and schwannomas). Melanomas can rarely arise in blue nevi. Clinically, the dark blue color may resemble a nodular melanoma. Usually, the clinical history of slow growth is what distinguishes the two. Small blue nevi can be followed clinically. Those in difficult locations to follow such as the scalp or sacrococcygeal area can be surgically removed.

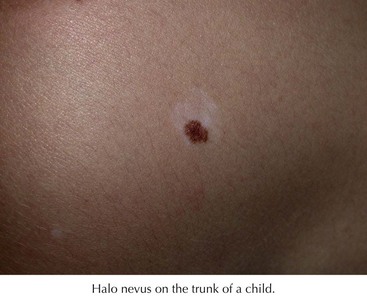

Halo Nevi

These are lesions that are characterized by a central pigmented nevus surrounded by an area of depigmentation (Figure 126-5). These occur most commonly in adolescents on the back. They occur in 5% of white children 6 to 15 years of age. The central area may darken but more commonly lightens or regresses over time. There are many lymphocytes surrounding the melanocytes on histology, suggesting an immunologic response to the nevus cells. Halo nevi may herald the onset of vitiligo. Regressing melanoma may also have an associated leukoderma, but typically it is not a symmetrical process as in the halo nevus. Full examination is indicated to rule out a concurrent melanoma. The decision to biopsy the central nevus is based on the same criteria as for other acquired nevi.

Bolognia JL. Too many moles. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:508.

DeDavid M, Orlow S, Provost N, et al. Neurocutaneous melanosis: clinical features of large congenital melanocytic nevi in patients with manifest central nervous system melanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:529-538.

Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, et al. Sunburns and the risk of cutaneous melanoma: does age matter? A comprehensive meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(8):614-627.

Frieden I, William M, Barkovich A. Giant congenital melanocytic nevi: brain magnetic resonance findings in neurologically asymptomatic children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:423-429.

Friedman RJ, Farber MJ, Warycha MA, et al. The “dysplastic” nevus. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(1):103-115.

Gelbarb SN, Tripp JM, Marghoob AA. Management of Spitz nevi: a survey of dermatologists in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:224-230.

Goodson AG, Grossman D. Strategies for early melanoma detection: approaches to the patient with nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5):719-735.

Huynh PM, Grant-Kels JM, Grin CM. Childhood melanoma: update and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:715-723.

Marghoob AA, Borrego JP, Halpern AC. Congenital melanocytic nevi: treatment modalities and management options. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:231-240.

Mateus C, Palangie A, Franck N, et al. Heterogeneity of skin manifestations in patients with Carney complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5):801-810.

Morgan CJ, Nyak N, Cooper A. Multiple Spitz naevi: a report of both variants with clinical and histopathological correlation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:368-371.

Prok LD, Arbuckle HA. Nevi in children: a practical approach to evaluation. Pediatr Ann. 2007;36:39-45.

Schaffer JV. Pigmented lesions in children: when to worry. Current Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):430-440.

Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Derm. 2001;137:172-178.

Tripp JM, Kopf AW, Marghoob AA, et al. Management of dysplastic nevi: a survey of fellows of the American academy of dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:674-682.